Final Report Global Broadband and Innovations Alliance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grameen Telecom and Voxiva Two Cases That Bridge the Digital Divide Through Telecommunication

Grameen Telecom and Voxiva Two cases that bridge the digital divide through telecommunication By Tabitha Bonilla and Theresa Eugenio 1 Outline • Grameen Phones – Telephone connectivity in Bangladesh – Introducing phone systems to rural villages • Voxiva – Healthcare concerns in Peru – Producing a system that promotes more urgent care 2 Case 1: Grameen Village Phone Program • Problem – 97% of Bangladesh homes have no telephone – 0.34 telephone lines per 100 people – 2 day trip to make a call 3 Grameen Solution • Twofold 1. Non-profit Grameen Telecom (GT) 2. For-profit Grameen Phone (GP) • Both branches of Grameen bank 4 Grameen Telecom • Village Phone Program – Started in 1997 – Pay-per-call system – Gives villages easily accessible mobile phone stations – Grameen Bank provides loans and training 5 GT Benefits • Financial – City calls cost 1.94 to 8.44 times as much – 2.64% to 9.8% of monthly income – 86% of calls used for financial purposes – 8% used explicitly to improve prices • Social – Empowers village women 6 Grameen Phone • National mobile phone service – Won license in 1996 – Began operations on March 26, 1997 – Primarily urban areas – Individually-owned systems 7 GP-GT Interaction • Demonstrates how complementary profit and non-profit organizations feed into one another • GP profits offset GT costs » -allows GT calls to be 50% off • Economic growth could lead to an eventual rise in GP customers 8 Measures of Success-GT • 165,000 subscribers as of August 2005 • Low cancellation rate- 2.18% 9 Measures of Success-GP 10 • About 63% -

Termination Rates at European Level January 2021

BoR (21) 71 Termination rates at European level January 2021 10 June 2021 BoR (21) 71 Table of contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 2 2. Fixed networks – voice interconnection ..................................................................... 6 2.1. Assumptions made for the benchmarking ................................................................ 6 2.2. FTR benchmark .......................................................................................................... 6 2.3. Short term evolution of fixed incumbents’ FTRs (from July 2020 to January 2021) ................................................................................................................................... 9 2.4. FTR regulatory model implemented and symmetry overview ............................... 12 2.5. Number of lines and market shares ........................................................................ 13 3. Mobile networks – voice interconnection ................................................................. 14 3.1. Assumptions made for the benchmarking .............................................................. 14 3.2. Average MTR per country: rates per voice minute (as of January 2021) ............ 15 3.3. Average MTR per operator ...................................................................................... 18 3.4. Average MTR: Time series of simple average and weighted average at European level ................................................................................................................. -

AFG- 0.45 $ 9370 Afghanistan-Mobile-AWCC

COUNTRYCODE DESCRIPTION RATE 93 Afghanistan-:-AFG- $ 0.45 9370 Afghanistan-Mobile-AWCC-:-AFG-MOBW $ 0.43 93711 Afghanistan-Mobile-AWCC-:-AFG-MOBW $ 0.43 9378 Afghanistan-Mobile-Etisalat-:-AFG-MOBE $ 0.40 9376 Afghanistan-Mobile-MTN-:-AFG-MOBA $ 0.50 9377 Afghanistan-Mobile-MTN-:-AFG-MOBA $ 0.50 937 Afghanistan-Mobile-Others-:-AFG-MOBZ $ 0.47 93744 Afghanistan-Mobile-Others-:-AFG-MOBZ $ 0.47 93747 Afghanistan-Mobile-Others-:-AFG-MOBZ $ 0.47 9372 Afghanistan-Mobile-Roshan-:-AFG-MOBR $ 0.38 9379 Afghanistan-Mobile-Roshan-:-AFG-MOBR $ 0.38 355 Albania-:-ALB- $ 0.35 35568 Albania-Mobile-AMC-:-ALB-MOBA $ 0.87 35567 Albania-Mobile-Eagle-:-ALB-MOBE $ 0.83 35566 Albania-Mobile-Others-:-ALB-MOBZ $ 0.86 35569 Albania-Mobile-Vodafone-:-ALB-MOBV $ 0.82 355422 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 355423 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 3554240 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 3554241 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 3554242 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 3554243 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 3554244 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 3554245 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 3554246 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 3554247 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 3554248 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 3554249 Albania-Tirana-:-ALB-TIR $ 0.35 213 Algeria-:-DZA- $ 0.13 21321 Algeria-Algiers-:-DZA-ALG $ 0.13 2137 Algeria-Mobile-Djezzy-:-DZA-MOBD $ 0.78 2136 Algeria-Mobile-Mobilis-:-DZA-MOBM $ 0.78 2131 Algeria-Mobile-Others-:-DZA-MOBZ $ 0.78 2139 Algeria-Mobile-Others-:-DZA-MOBZ $ 0.78 2135 Algeria-Mobile-Wataniya-:-DZA-MOBW $ 1.37 376 Andorra-:-AND- $ 0.04 3763 Andorra-Mobile-:-AND-MOB -

The Promise of Ubiquity Mobile As Media Platform in the Global South

EUROPE THE PROMISE OF UBIQUITY MOBILE AS MEDIA PLATFORM IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH 7 2 2 8 2 8 INTERNEWS EUROPE 3 EUROPE THE PROMISE OF UBIQUITY MOBILE AS MEDIA PLATFORM IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH INTERNEWS EUROPE THE PROMISE OF UBIQUITY Credits Produced by John West for Internews Europe © 2008. All rights reserved. This report is available in PDF online at http://www.internews.eu This publication was generously supported by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Internews Network. 2 CONTENTS Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Reach – mobile now matches TV in the South 5 2.1. 2006-8 Explosion 5 2.2. Predicted continued growth 6 2.3. Generalised pattern 7 2.4. South not G7, East or Middle East 8 2.5. Least-Developed Countries 9 2.6. The decision-maker’s bubble 10 2.7. A BOP business 11 a) MNOs and the decline of ARPU 11 b) Handset manufacturers 13 c) Government: critical mass of competition 13 3. Case Studies 15 3.1. Ken Banks – FrontlineSMS 15 3.2. Paul Meyer – Voxiva LLC 16 3.3. Jasmine News Service 17 3.4. Emmanuel de Dinechin – Altai Consulting 18 3.5. Jonathan Marks, Critical Distance 19 3.6. Mike Grenville – 160Characters.org 20 3.7. Bobby Soriano – mobile in the Philippines 21 3.8. Illico Elia, Thomson Reuters Mobile Products 22 3.9. Jan Blom, designer, Nokia, Bangalore 23 4. The implications for southern media 25 4.1. Working Conclusions 25 a) If you don’t do it, someone else will 25 b) It’s only just beginning 25 c) Text is everywhere, voice is (surprisingly) nowhere 25 d) Know what you’re offering 25 e) Know Your Market 26 f) It’s tough down the food chain – strike out on your own if you can 26 g) Look Everywhere for the Business Model 26 h) Broadcast point of departure: participation 26 i) Print point of departure: the right snippet of data 26 5. -

NASA Contractor Report 172501 I/ --- / 5 '7"12.-I

NASA Contractor Report 172501 |_&SA-CB-172501} VO_S_A_: A C£#._DTEH _87- 18329 }}CGBAM FOR CALC_LATIBG LA_£BAI-DIRECTIGNAL S_ABIII_Y DEBIIAII_ES WITH VC£_X FLOW £1_ECI (Kansas _niv. Center fez _esearch, Unclas 43373 Inc.} 260 p CSCL 09B G3/61 VORSTAB - A COMPUTER PROGRAM FOR CALCULATING LATERAL-DIRECTIONAL STABILITY DERIVATIVES WITH VORTEX FLOW EFFECT C. Edward Lan i/_---_ / THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS CENTER FOR RESEARCH, INC. Flight Research Laboratory Lawrence, Kansas 5 _'7"12.-I i Grant NAG1-134 January 1985 January 31, 1987 Date for general release National Aeronautics and Space Administration Langley Research Center Hampton, Virginia 23665 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Introduction i Summary of the Theoretical Method i Program Capabilities 5 Input Data Format 7 Output Variables 26 Program Job Control Set-Up 31 Sample Input and Output 32 References 84 Appendix Fortran Program Listing 86 INTRODUCTION This report describes the usage of a computer program for calculating lateral-directional stability and control derivatives as described in reference i. The method is applicable to wing- body combinations in subsonic flow. In the following, a summary of the theoretical method, program capabilities, input format, output variables and program job control set-up are described. Then, input data of sample test cases and the corresponding output are given. The program listing is presented at the end. SUMMARY OF THE THEORETICAL METHOD The method is based on the Prandtl-Glauert equation in subsonic flow. The wing is assumed to be thin, so that thickness effect is not included. In the following, theoretical representation of the effects of wings, vortex flow and fuselage is summarized. -

Comodo Threat Intelligence

Comodo Threat Intelligence Lab SPECIAL REPORT: AUGUST 2017 – IKARUSdilapidated Locky Part II: 2nd Wave of Ransomware Attacks Uses Your Scanner/Printer, Post Office Billing Inquiry THREAT RESEARCH LABS Locky Ransomware August 2017 Special Report Part II A second wave of new but related IKARUSdilapidated Locky ransomware attacks has occurred, building on the attacks discovered by the Comodo Threat Intelligence Lab (part of Comodo Threat Research Labs) earlier in the month of August 2017. This late August campaign also uses a botnet of “zombie computers” to coordinate a phishing attack which sends emails appearing to be from your organization’s scanner/printer (or other legitimate source) and ultimately encrypts the victims’ computers and demands a bitcoin ransom. SPECIAL REPORT 2 THREAT RESEARCH LABS The larger of the two attacks in this wave presents as a scanned image emailed to you from your organization’s scanner/printer. As many employees today scan original documents at the company scanner/printer and email them to themselves and others, this malware-laden email will look very innocent. The sophistication here includes even matching the scanner/printer model number to make it look more common as the Sharp MX2600N is one of the most popular models of business scanner/printers in the market. This second wave August 2017 phishing campaign carrying IKARUSdilapidated Locky ransomware is, in fact, two different campaigns launched 3 days apart. The first (featuring the subject “Scanned image from MX-2600N”) was discovered by the Lab to have commenced primarily over 17 hours on August 18th and the second (a French language email purportedly from the French post office featuring a subject including “FACTURE”) was executed over a 15-hour period on August 21st, 2017. -

Community Development District

Rivers Edge II Community Development District September 18, 2019 Rivers Edge II Community Development District 475 West Town Place, Suite 114, St. Augustine, Florida 32092 Phone: 904-940-5850 - Fax: 904-940-5899 September 17, 2019 Board of Supervisors Rivers Edge II Community Development District Dear Board Members: The Rivers Edge II Community Development District Board of Supervisors Meeting is scheduled for Wednesday, September 18, 2019 at 10:30 a.m. at the RiverTown Amenity Center, 156 Landing Street, St. Johns, Florida. Following is the revised agenda for the meeting: I. Call to Order II. Public Comment III. Affidavits of Publication IV. Approval of the Minutes of the August 21, 2019 Meeting V. Public Hearing on the Imposition of Special Assessments A. Consideration of Resolution 2019-15, Equalizing and Levying Debt Assessments VI. Consideration of Amendment #1 to the Traffic Control Agreement with St. Johns County VII. Staff Reports A. District Counsel B. District Engineer C. District Manager D. General Manager – Report VIII. Financial Reports A. Balance Sheet and Income Statement B. Consideration of Funding Request No. 12 C. Check Register IX. Supervisors’ Requests and Audience Comments X. Next Scheduled Meeting – October 16, 2019 at 10:30 a.m. at the RiverTown Amenity Center XI. Adjournment Enclosed under the third order of business are the affidavits of publication for the public hearing equalizing and levying special assessments. Enclosed under the fourth order of business is a copy of the minutes of the August 21, 2019 meeting for your review and approval. The fifth order of business is the public hearing on the imposition of special assessments. -

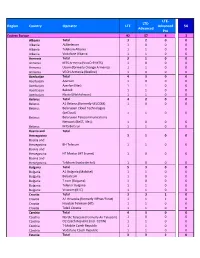

Prepared for Upload GCD Wls Networks

LTE‐ LTE‐ Region Country Operator LTE Advanced 5G Advanced Pro Eastern Europe 92 57 4 3 Albania Total 32 0 0 Albania ALBtelecom 10 0 0 Albania Telekom Albania 11 0 0 Albania Vodafone Albania 11 0 0 Armenia Total 31 0 0 Armenia MTS Armenia (VivaCell‐MTS) 10 0 0 Armenia Ucom (formerly Orange Armenia) 11 0 0 Armenia VEON Armenia (Beeline) 10 0 0 Azerbaijan Total 43 0 0 Azerbaijan Azercell 10 0 0 Azerbaijan Azerfon (Nar) 11 0 0 Azerbaijan Bakcell 11 0 0 Azerbaijan Naxtel (Nakhchivan) 11 0 0 Belarus Total 42 0 0 Belarus A1 Belarus (formerly VELCOM) 10 0 0 Belarus Belarusian Cloud Technologies (beCloud) 11 0 0 Belarus Belarusian Telecommunications Network (BeST, life:)) 10 0 0 Belarus MTS Belarus 11 0 0 Bosnia and Total Herzegovina 31 0 0 Bosnia and Herzegovina BH Telecom 11 0 0 Bosnia and Herzegovina HT Mostar (HT Eronet) 10 0 0 Bosnia and Herzegovina Telekom Srpske (m:tel) 10 0 0 Bulgaria Total 53 0 0 Bulgaria A1 Bulgaria (Mobiltel) 11 0 0 Bulgaria Bulsatcom 10 0 0 Bulgaria T.com (Bulgaria) 10 0 0 Bulgaria Telenor Bulgaria 11 0 0 Bulgaria Vivacom (BTC) 11 0 0 Croatia Total 33 1 0 Croatia A1 Hrvatska (formerly VIPnet/B.net) 11 1 0 Croatia Hrvatski Telekom (HT) 11 0 0 Croatia Tele2 Croatia 11 0 0 Czechia Total 43 0 0 Czechia Nordic Telecom (formerly Air Telecom) 10 0 0 Czechia O2 Czech Republic (incl. CETIN) 11 0 0 Czechia T‐Mobile Czech Republic 11 0 0 Czechia Vodafone Czech Republic 11 0 0 Estonia Total 33 2 0 Estonia Elisa Eesti (incl. -

Dr. Neuhaus Telekommunikation Mobile Network Code

Dr. Neuhaus Telekommunikation Mobile Network Code The Mobile Country Code (MCC) is the fixed country identification. The Mobile Network Code (MNC) defines a GSM‐, UMTS‐, or Tetra radio network provider. This numbers will be allocates June 2011 autonomus from each country. Only in the alliance of bothscodes (MCC + MNC) the mobile radio network can be identified. All informations without guarantee Country MCC MNC Provider Operator APN User Name Password Abkhazia (Georgia) 289 67 Aquafon Aquafon Abkhazia (Georgia) 289 88 A-Mobile A-Mobile Afghanistan 412 01 AWCC Afghan Afghanistan 412 20 Roshan Telecom Afghanistan 412 40 Areeba MTN Afghanistan 412 50 Etisalat Etisalat Albania 276 01 AMC Albanian Albania 276 02 Vodafone Vodafone Twa guest guest Albania 276 03 Eagle Mobile Albania 276 04 Plus Communication Algeria 603 01 Mobilis ATM Algeria 603 02 Djezzy Orascom Algeria 603 03 Nedjma Wataniya Andorra 213 03 Mobiland Servei Angola 631 02 UNITEL UNITEL Anguilla (United Kingdom) 365 10 Weblinks Limited Anguilla (United Kingdom) 365 840 Cable & Antigua and Barbuda 344 30 APUA Antigua Antigua and Barbuda 344 920 Lime Cable Antigua and Barbuda 338 50 Digicel Antigua Argentina 722 10 Movistar Telefonica internet.gprs.unifon.com. wap wap ar internet.unifon Dr. Neuhaus Telekommunikation Mobile Network Code The Mobile Country Code (MCC) is the fixed country identification. The Mobile Network Code (MNC) defines a GSM‐, UMTS‐, or Tetra radio network provider. This numbers will be allocates June 2011 autonomus from each country. Only in the alliance of bothscodes (MCC + MNC) the mobile radio network can be identified. All informations without guarantee Country MCC MNC Provider Operator APN User Name Password Argentina 722 70 Movistar Telefonica internet.gprs.unifon.com. -

SDG ICT Playbook 2015 Page 1 / 66 Acknowledgments

SDG ICT Playbook 2015 Page 1 / 66 Acknowledgments SUPPORTERS OF THIS PLAYBOOK EDITORS, DESIGNERS AND CONTRIBUTORS Carol Bothwell Lauren Woodman Lisa Obradovich Director, Technology Chief Executive Officer Global Programs Manager Innovation for Development NetHope NetHope Catholic Relief Services Emily Fruchterman Renee Wittemyer Yohan Perera Program & Operations Director of Social Graphic Designer Coordinator Innovation TechChange TechChange Intel Donna McMahon Christopher Neu Director of Planning & Chief Operating Officer Administration TechChange Catholic Relief Services Please see the appendix for a list of individuals and organizations that contributed their expertise to this effort. NetHope would like to take this opportunity to thank Lisa Obradovich, the project manager for development of the SDG ICT Playbook and Carol Bothwell, the primary author and executive editor. SDG ICT Playbook 2015 Page 2 / 66 Acknowledgments NetHope is a collaboration between the 43 leading international nonprofit organizations and the technology sector. NetHope works with its members and corporate partners to foster collaboration and innovation and leverage the full potential of technology to support development and humanitarian programs. NetHope has extensive experience in delivering programs in partnership with its members and corporate partners. For more information visit www.nethope.org. For over 40 years, Intel has created technologies that transform the way people live, work and learn. We are committed to connecting people to their potential and empowering them to seize the opportunities that technology makes possible. Collaborating with others, we champion programs that tap the power of technology to create value for society, expand access, and foster economic empowerment. At Intel, we believe that together, we can create a better future. -

The Value of Information and Communication Technologies in Humanitarian Relief Efforts

Mark Summer The Value of Information and Communication Technologies in Humanitarian Relief Efforts Innovations Case Narrative: Inveneo I was in a meeting on January 12, 2010, when I heard about the earthquake in Haiti. The moment is still vivid in my mind because we had been working for months with our partner, the EKTA Foundation, on a plan to make information and communication technologies (ICTs) accessible and sustainable in rural areas of Haiti. I had planned to fly to Port-au-Prince with another Inveneo cofounder on January 15, where we were to stay at the now-collapsed Hotel Montana to research opportunities and connect with the local tech community. Then the earthquake struck. It wasn’t until hours later, after trying to reach our Haitian contacts, that we realized the extent of the devastation. Our connections with Haitian colleagues made our commitment immediate and more personal. Later that day, we met with our partner NetHope1, a collaboration of 31 of the world’s leading international humanitarian organizations that share technology best practices. Our conversation immediately turned to the tragedy in Haiti. We had been working with NetHope on a large-scale ICT project for relief camps across the world, but as they counted the number of their member organizations directly affected by the earthquake (20), our conversation shifted to ways we could address their urgent needs. For many disaster response veterans, the Haiti earthquake represents a turning point in our collective thinking about the value of ICTs in humanitarian relief efforts. A range of ICT-focused initiatives have demonstrated that technology— from accessing detailed maps of the affected area, to turning simple SMS messages into life-saving systems, to establishing broadband Internet connectivity to humanitarian organizations—improves both the speed and substance of relief efforts. -

Cisco Project Report

DadaabNet Project Report March 2014 “The customer is always right” An unprecedented drought and famine across Somalia, coupled with the long-standing civil war, resulted in a massive influx of refugees to Dadaab1, Kenya during the summer of 2011 and throughout 2012. The refugee camp’s population spiked from 300,000 to well over 500,000, resulting in a need for humanitarian organizations to quickly ramp up operations. Given that Dadaab grew has enabled shared resources, to over five times the number of collaborative communications refugees it was originally designed and response efforts, and an array for, there were infrastructure “When disaster strikes, of workforce and community inadequacies and essential service the immediate needs are development programs. Access to capacity and logistical challenges obvious: food, water, shelter DadaabNet has also been extended — all of which could be offset by and medical supplies, but to refugee youth, presenting an better connectivity. none of these necessities invaluably empowering opportunity reach survivors without Recognizing this critical need, over for education and vocational a robust communication 16 organizations came together training, and, for some, a first network to enable relief behind an initiative to deliver high- chance to connect to the outside workers to save lives.” speed, low-cost Internet access world. It may soon provide many Lynda Kigera, Save the via an innovative and replicable with their first access to health care Children network model. With the successful through Tele-Health technologies implementation of DadaabNet, aid and virtual access to Doctors. agencies in Dadaab were provided Project Overview with the reliable access needed to improve operations and save lives.