Introduction Methods Results

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Heritage Values and to Identify New Values

FLORISTIC VALUES OF THE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS WORLD HERITAGE AREA J. Balmer, J. Whinam, J. Kelman, J.B. Kirkpatrick & E. Lazarus Nature Conservation Branch Report October 2004 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment (World Heritage Area Vegetation Program). Commonwealth Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment or those of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. ISSN 1441–0680 Copyright 2003 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment. Published by Nature Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph: Alpine bolster heath (1050 metres) at Mt Anne. Stunted Nothofagus cunninghamii is shrouded in mist with Richea pandanifolia scattered throughout and Astelia alpina in the foreground. Photograph taken by Grant Dixon Back Cover Photograph: Nothofagus gunnii leaf with fossil imprint in deposits dating from 35-40 million years ago: Photograph taken by Greg Jordan Cite as: Balmer J., Whinam J., Kelman J., Kirkpatrick J.B. & Lazarus E. (2004) A review of the floristic values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2004/3. Department of Primary Industries Water and Environment, Tasmania, Australia T ABLE OF C ONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................................1 1. -

Wellington Park Historic Tracks and Huts Network Comparative Analysis

THE HISTORIC TRACK & HUT NETWORK OF THE HOBART FACE OF MOUNT WELLINGTON Interim Report Comparative Analysis & Significance Assessment Anne McConnell MAY 2012 For the Wellington Park Management Trust, Hobart. Anne D. McConnell Consultant - Cultural Heritage Management, Archaeology & Quaternary Geoscience; GPO Box 234, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001. Background to Report This report presents the comparative analysis and significance assessment findings for the historic track and hut network on the Hobart-face of Mount Wellington as part of the Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project. This report is provided as the deliverable for the second milestone for the project. The Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project is a project of the Wellington Park Management Trust. The project is funded by a grant from the Tasmanian government Urban Renewal and Heritage Fund (URHF). The project is being undertaken on a consultancy basis by the author, Anne McConnell. The data contained in this assessment will be integrated into the final project report in approximately the same format as presented here. Image above: Holiday Rambles in Tasmania – Ascending Mt Wellington, 1885. [Source – State Library of Victoria] Cover Image: Mount Wellington Map, 1937, VW Hodgman [Source – State Library of Tasmania] i CONTENTS page no 1 BACKGROUND - THE EVOLUTION OF 1 THE TRACK & HUT NETWORK 1.1 The Evolution of the Track Network 1 2.2 The Evolution of the Huts 18 2 A CONTEXT FOR THE TRACK & HUT 29 NETWORK – A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 2.1 -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal for SPONSORING BROKER Kaz Capital Pty Ltd AFSL: 384738

ACN 156 369 336 PROSPECTUS For the Offer of 20,000,000 Shares at an offer price of 20 cents each to raise up to $4,000,000 with a Minimum Subscription of $3,000,000 with 1 free attaching Listed Option exercisable at 30 cents on or before 31 March 2016 for every Share subscribed for and issued. Oversubscriptions of up to a further 5,000,000 Shares at an issue price of 20 cents each to raise up to a further $1,000,000 with 1 free attaching Listed Option for every Share subscribed for and issued may be accepted. For personal use only SPONSORING BROKER Kaz Capital Pty Ltd AFSL: 384738 Important Information This Prospectus provides important information to assist prospective investors in deciding whether or not to invest in the Company. It should be read in its entirety. If you do not understand it, you should consult your professional advisers. THE SECURITIES OFFERED UNDER THIS PROSPECTUS ARE OF A SPECULATIVE NATURE. CORPORATE DIRECTORY Directors Solicitors Peter McNeil Non-Executive Chairman Steinepreis Paganin Robert McNeil Managing Director/CEO Level 4 16 Milligan Street Graham Fish Non-Executive Director PERTH WA 6000 Jay Stephenson Non-Executive Director Page Seager Company Secretary RACT House Level 2 Lisa Hartin 179 Murray Street HOBART TAS 7000 Registered Office 2 Village High Road Independent Geologist BENOWA QLD 4217 Aimex Geophysics Pty Ltd Telephone: +61 7 5564 8823 PO Box 8356 Facsimile: +61 7 5597 7215 Gold Coast Mail Centre Website: www.torquemining.com.au BUNDALL QLD 9726 Email: [email protected] Investigating Accountant -

Alluvial Gold

GSHQI\ TASMANIA DEPARTMENT OF RESOURCES AND ENERGY DIVISION OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES 1991 MINERAL RESOURCES OFTASMANIA 11 Alluvial gold by R. S. Bottrill B.Sc. (Hons). M.Sc. DIVISION OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES ISBN 0 7246 2083 4 GPO BOX 56, ROSNY PARK, TASMANIA 7018 ISSN 0313-1998 BoTIRILL, R. S. 1991. Alluvial gold. Miner. Resour. Tasm. II. ISBN 0 7246 2083 4 ISSN0313-2043 TECHNICAL EDITOR, E. L. Martin TEXT INpUT, C. M. Humphries Mineral Resources o/Tasmania is a continuation of Geological Survey Minerai Resources ALLUVIAL GOlD 3 CONTENTS Introduction .. 5 1. Mangana-Mathinna-Alberton 5 2. Gladstone-Derby . 5 3. Lisle ....... 5 4. Back Creek-Lefroy 5 5. Beaconsfield 6 6. Moina . ... 6 7. Wynyard .. 6 8. Arthur River 6 9. Corinna-Savage River .. ... 6 10. Ring River-Wilson River 6 11. Lyell-Darwin . ... 7 12. Jane River . 7 13. Cygnet 7 14. Others . .. 7 Discussion . 7 Acknowledgements . ..... 7 References . .... .. 9 Appendix A: Occurrences of alluvial gold in Tasmania . ..... .• •... .11 LIST OF FIGURES 1. Areas of major alluvial gold production in Tasmania ...... ... 4 2. Polished section of a gold grain from the Lisle goldfield, showing a porous I skeletal structure . 8 3. Polished section of a gold grain from the Lisle goldfield, showing a rim of silver-depleted gold on silver..,nriched gold ..... ......................... .... ......... 8 4 MlNERAL RESOURCES OF TASMANIA II 0 1+4 Scm PRINCIPAL AREAS OF ALLUVIAL GOLD PRODUCTION IN TASMANIA o 100 kilometres TN I 1470 Figure 1. Areas of major alluvial gold produclion in Tasmania described in the lext- 1: Mangana-Mathinna-Alberton, 2: Gladslon&-Derby, 3: Lisle, 4: Back Creek-Lefroy, 5: Beaconsfield, 6: Moina, 7: Wynyard, 8: Arthur River, 9: Corinna-Savage River, 10: Ring River-Wilson River, 11 : Lyell-Darwin, 12: Jane River, 13: Cygnet. -

The Aboriginal Names of Rivers in Australia Philologically Examiped

The Aboriginal Names of Rivers in Australia Philologically Examiped. By the late REV. PETER 1I'L\.CPIIERSON, 1I'LA. [Read before the Royal Society qf N.S. W., 4 August, 188G.J IT is the purpose of this paper to pass in review the names which the aborigines of Australia have given to the rivers, streams, and waters generally of the country which they llave occupied. More specifically, attention will bo directed to the principles if discover able on which the names have been given. In this inquiry con stant regard will be had to the question whether the Aborigines have followed the same general principles which are found to pre vail in other languages of th"l world. -Without further preface, it may be stated that all available vocabularies will be searched for the terms used to designate water, whether in the shape of rivers, brooks, or creeks; expansions of water, as oceans, seas, bays, or harbours; lakes, lagoons, pools, or waterboles; swamps, or maJ"Shes; springs, or wells; rain, or ,vaterfalls; and any other form in which water is the important element. M, imitative of the sound of Waters. Words for Watel' containing the letter jJf. To make a beginning, let one of the imitative root words for water be chosen as the basis of experiment. There is the letter Jl, which represents the It1wnming sound pertaining to water, whether flowing in streams or moved by tides and winds in ocean expanses. In carrying out the experiment the method followed will be (1) to examine the vocabularies for root-words designating water in any of the shapes already indicated, and embodying in the present case the letter 1n; (2) to examine the gazetteers of the several colonies, to ascertain how the same letter is embodied in the actual names of rivers, streams, and waters generally; and (3) to compare the results with the root words for water in other part-s of the world. -

Plant Miniatures Scholarship Report Banksia Exploration

Spring 2020 Plant miniatures Scholarship Report Banksia exploration 15th Biennial Exhibition 19 September - 31 December 2020 Virtual exhibition To see this fabulous exhibition visit www.rbgfriendsmelbourne.org All art available for purchase Agapanthus Seed Head By Vicki Philipson IN THIS ISSUE The Friends of the Royal Botanic Gardens, 5 Volunteer Profile Melbourne Inc.was formed to stimulate further interest in the Gardens and the 6 From the Gardens National Herbarium and to support and assist them whenever possible. 8 Growing Friends 10 Events Friends’ Office Patron Jill Scown The Honourable 16 Plant Crafts Karlene Taylor Linda Dessau AC Georgina Ponce de Governor of Victoria Banksia Exploration 18 Leon Huerta President Mary Ward 22 Illustrators Botanic News ISSN 08170-650 Vice-Presidents 23 Scholarship Report Editor Lynsey Poore Meg Miller Catherine Trinca 26 Photo Group E: editor.botnews@ Secretary frbgmelb.org.au Adnan Mansour Friends’ Calendar 28 Graphic Designer Treasurer Andrea Gualteros Mark Anderson eNEWS Council Editor Prof. Tim Entwisle Victoria English Sue Broadbent Jill Scown Sue Foran E: [email protected] David Forbes Printer Will Jones Design to Print Solutions Meg Miller Printed on Nicola Rollerson 100 per cent Australian Lisa Steven recycled paper Conveners Print Post Approved PP 345842/10025 Botanical Illustrators PAGE 6 A12827T Sue Foran Events Advertising Lisa Steven Full and half page inside front and back covers Growing Friends are avalaible. Single Michael Hare DL inserts will also be Helping Hands accepted. Sue Hoare Membership/Marketing Gate Lodge, Nicola Rollerson 100 Birdwood Avenue, Melbourne Vic 3004 Photo Group T: (03) 9650 6398 David Forbes ABN 43 438 335 331 Plant Craft Cottage Christina Gebhardt E: [email protected] Volunteers PAGE 18 W: rbgfriendsmelbourne.org Diana Barrie : @friendsrbgmelb Friends’ Trust Fund : @friendsroyalbotanicgardensmelb William Jones Mark Calder Janet Thomson OAM Catherine Trinca The Friends of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne Inc. -

Ecology of Proteaceae with Special Reference to the Sydney Region

951 Ecology of Proteaceae with special reference to the Sydney region P.J. Myerscough, R.J. Whelan and R.A. Bradstock Myerscough, P.J.1, Whelan, R.J.2, and Bradstock, R.A.3 (1Institute of Wildlife Research, School of Biological Sciences (A08), University of Sydney, NSW 2006; 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong, NSW 2522; 3Biodiversity Research and Management Division, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, PO Box 1967, Hurstville, NSW 1481) Ecology of Proteaceae with special reference to the Sydney region. Cunninghamia 6(4): 951–1015. In Australia, the Proteaceae are a diverse group of plants. They inhabit a wide range of environments, many of which are low in plant resources. They support a wide range of animals and other organisms, and show distinctive patterns of distribution in relation to soils, climate and geological history. These patterns of distribution, relationships with nutrients and other resources, interactions with animals and other organisms and dynamics of populations in Proteaceae are addressed in this review, particularly for the Sydney region. The Sydney region, with its wide range of environments, offers great opportunities for testing general questions in the ecology of the Proteaceae. For instance, its climate is not mediterranean, unlike the Cape region of South Africa, south- western and southern Australia, where much of the research on plants of Proteaceae growing in infertile habitats has been done. The diversity and abundance of Proteaceae vary in the Sydney region inversely with fertility of habitats. In the region’s rainforest there are few Proteaceae and their populations are sparse, whereas in heaths in the region, Proteaceae are often diverse and may dominate the canopy. -

Verification of the Heritage Value of ENGO-Proposed Reserves

IVG REPORT 5A Verification of the heritage value of ENGO-proposed reserves Verification of the Heritage Value of ENGO-Proposed Reserves IVG Forest Conservation REPORT 5A 1 March 2012 IVG REPORT 5A Verification of the heritage value of ENGO-proposed reserves IVG Forest Conservation Report 5A Verification of the Heritage Value of ENGO-Proposed Reserves An assessment and verification of the ‘National and World Heritage Values and significance of Tasmania’s native forest estate with particular reference to the area of Tasmanian forest identified by ENGOs as being of High Conservation Value’ Written by Peter Hitchcock, for the Independent Verification Group for the Tasmanian Forests Intergovernmental Agreement 2011. Published February 2012 Photo credits for chapter headings: All photographs by Rob Blakers With the exception of Chapter 2 (crayfish): Todd Walsh All photos copyright the photographers 2 IVG REPORT 5A Verification of the heritage value of ENGO-proposed reserves About the author—Peter Hitchcock AM The author’s career of more than 40 years has focused on natural resource management and conservation, specialising in protected areas and World Heritage. Briefly, the author: trained and graduated—in forest science progressing to operational forest mapping, timber resource assessment, management planning and supervision of field operations applied conservation—progressed into natural heritage conservation including conservation planning and protected area design corporate management—held a range of positions, including as, Deputy Director -

Knightia Excelsa

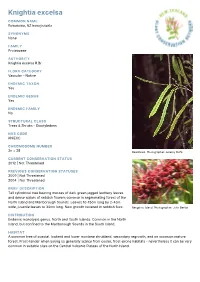

Knightia excelsa COMMON NAME Rewarewa, NZ honeysuckle SYNONYMS None FAMILY Proteaceae AUTHORITY Knightia excelsa R.Br. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS Yes ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE KNIEXC CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 28 Rewarewa. Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | Not Threatened PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened BRIEF DESCRIPTION Tall cylindrical tree bearing masses of dark green jagged leathery leaves and dense spikes of reddish flowers common in regenerating forest of the North Island and Marlborough Sounds. Leaves 10-15cm long by 2-4cm wide, juvenile leaves to 30cm long. New growth covered in reddish fuzz. Rangitoto Island. Photographer: John Barkla DISTRIBUTION Endemic monotypic genus. North and South Islands. Common in the North Island, but confined to the Marlborough Sounds in the South Island. HABITAT A common tree of coastal, lowland and lower montane shrubland, secondary regrowth, and on occasion mature forest. Frost-tender when young so generally scarce from cooler, frost-prone habitats - nevertheless it can be very common in suitable sites on the Central Volcanic Plateau of the North Island. FEATURES Tall tree with columnar (fastigiate) growth-form up to 30 m tall. Trunk up to 1 m diam. Bark dark brown. Branches erect, fastigiate, at first angled, clad in red-brown (rust-coloured), velutinous, tomentum. Juvenile leaves yellow- green, 150-300(-400) x 10-15 mm, narrowly linear-lanceolate, sometimes forked 2,3 or 4 times, margins acutely serrated. Adult leaves dark green, 100-150(-200) x 25-40 mm, broad lanceolate to narrow-oblong or oblong, sometimes obovate, occasionally forked, rigid, bluntly and coarsely serrated, covered in deciduous velutinous red- brown pubescence. -

NORTHLAND Acknowledgements

PLANT ME INSTEAD! NORTHLAND Acknowledgements Thank you to the following people and organisations who helped with the production of this booklet: Northland Regional Council staff, and Department of Conservation staff, Northland, for participation, input and advice; John Barkla, Jeremy Rolfe, Trevor James, John Clayton, Peter de Lange, John Smith-Dodsworth, John Liddle (Liddle Wonder Nurseries), Clayson Howell, Geoff Bryant, Sara Brill, Andrew Townsend and others who provided photos; Sonia Frimmel (What’s the Story) for design and layout. While all non-native alternatives have been screened against several databases to ensure they are not considered weedy, predicting future behaviour is not an exact science! The only way to be 100% sure is to use ecosourced native species. Published by: Weedbusters © 2011 ISBN: 978-0-9582844-9-3 Get rid of a weed, plant me instead! Many of the weedy species that are invading and damaging our natural areas are ornamental plants that have ‘jumped the fence’ from gardens and gone wild. It costs councils, government departments and private landowners millions of dollars, and volunteers and community groups thousands of unpaid hours, to control these weeds every year. This Plant Me Instead booklet profiles the environmental weeds of greatest concern to those in your region who work and volunteer in local parks and reserves, national parks, bush remnants, wetlands and coastal areas. Suggestions are given for locally-sold non-weedy species, both native and non- native, that can be used to replace these weeds in your garden. We hope that this booklet gives you some ideas on what you can do in your own backyard to help protect New Zealand’s precious environment. -

Armillaria Root Rot a New Disease of Cut- Flower Proteas in South Africa

10E - Armillaria root rot A new disease of cut- flower proteas in South Africa s. Denman', M .P.A . Ccetaee", B.D. Wingfield', M.J. Wingfield' INTRODUCTION and P. W. Crous '. Armillaria spp. are voracious pathogens of tree s and I Deportment of Plant Pathology, University of shrubs throughout the world. They survive either as Stellenbosch. Privote Bog XI, Motieland 7602. pathogens, saprobes or perthobes (an organism able 2Departme nt of Genetics, Tree Patholo gy Co to utilise dead ti s sues in living hosts) of woody operative Programme (TPCP), Fore stry and material(Gregory et al. ,1991). As facultat ive Agriculturol Biot echnology Institute (FABI), necrotrophs (pathogens) these fun gi kill living tissues University of Pret orio, Pretoria 0002. of woody hosts and then utilise the tissues as a nutrient JDepartment of Microbiology and Plant Pathology, sour ce (Kilc et al., 1991). In th e sap robic mode, Tree Pathology Co-operotive Progromme (TPCP) , Armillaria spp. 3fC wood decomposers aiding the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute recycling of nutri ents in ecosystems. Pathogenic (FABI), University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002. A rmill aria spp. ca us e major los s e s to for e stry (especially nati ve forests but also to co mme rcial plantations) world-wide, and also occur on fruit trees and ornamental plants. They have cause d losses to Taxonomy and Identification Proteaceae in Africa (Kenya, Tanzania, South Mrica), The taxonomy of Armilloria has been Australia, Madeira, New Zeal and, United States of problematic mainl y because it was assumed America (California, Hawaii ) and Zimbabwe. -

Energetics and Foraging Behaviour of the Platypus Ornithorhynchus Anatinus

Energetics and foraging behaviour of the Platypus Ornithorhynchus anatinus by Philip Bethge (Dipl.-Biol.) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, April 2002 Energetics and foraging behaviour of the platypus Declaration of originality This thesis contains no material, which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknow- ledged in the thesis. To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published or written by an- other person except where due acknowledgment is made in the text. ------------------------------------------------ 2 Energetics and foraging behaviour of the platypus Statement of authority of access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. ------------------------------------------------ 3 Energetics and foraging behaviour of the platypus For Tom, Louise, Karl, Albert, Eric, Fritz, Gerda, Hilde, Isolde, Julia, Konrad, Lydia 4 Energetics and foraging behaviour of the platypus Abstract In this work, behavioural field studies and metabolic studies in the labo- ratory were conducted to elucidate the extent of adaptation of the platypus Or- nithorhynchus anatinus to its highly specialised semiaquatic lifestyle. Energy requirements of platypuses foraging, resting and walking were measured in a swim tank and on a conventional treadmill using flow-through respirometry. Foraging behaviour and activity pattern of platypuses in the wild were investi- gated at a sub-alpine Tasmanian lake where individuals were equipped with combined data-logger-transmitter packages measuring foraging activity or dive depth and ambient temperature.