Regional Airport Users' Action Group and Geoff J Breust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Airline and Aircraft Movement Growth “Airports...Are a Vital Part of Ensuring That Our Nation Is Able to Be Connected to the Rest of the World...”

CHAPTER 5 AIRLINE AND AIRCRAFT MOVEMENT GROWTH “AIRPORTS...ARE A VITAL PART OF ENSURING THAT OUR NATION IS ABLE TO BE CONNECTED TO THE REST OF THE WORLD...” THE HON WARREN TRUSS, DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER 5 Airline and aircraft movement growth The volume of passenger and aircraft movements at Canberra Airport has declined since 2009/2010. In 2013/2014 Canberra Airport will handle approximately 2.833 million passengers across approximately 60,000 aircraft movements, its lowest recorded passenger volume since 2007/2008. The prospects for a future return to growth however are strong. Canberra Airport expects a restoration of volume growth in 2015/2016 and retains confidence in the future of the aviation market in Canberra, across Australia, and particularly the Asia Pacific region. Over the next 20 years passenger numbers at Canberra Airport are projected to reach 9 million passengers per annum with some 153,000 aircraft movements in 2033/2034. Canberra Airport, with its extensive infrastructure upgrades in recent years, is well positioned to meet forecast demand with only minor additional infrastructure and capitalise on growth opportunities in the regional, domestic and international aviation markets. 5.1 OVERVIEW Globally, the aviation industry has experienced enormous change over the past 15 years including deregulation of the airline sector, operational and structural changes in the post-September 11 2001 environment, oil price shocks, the collapse of airlines as a result of the global financial crisis (GFC), and the rise of new global players in the Middle East at the expense of international carriers from traditional markets. Likewise, Australia has seen enormous change in its aviation sector – the demise of Ansett, the emergence of Virgin Australia, Jetstar, and Tiger Airways, the subsequent repositioning of two out of three of these new entrant airlines and, particularly in the Canberra context, the collapse of regional airlines. -

MEDIA RELEASE THURSDAY 18 MARCH Major Players Commit To

MEDIA RELEASE THURSDAY 18 MARCH Major players commit to new industrial precinct at Bankstown Airport in South West Sydney Sydney, Australia 18 March 2021 – Hellmann Worldwide Logistics, Sydney Freezers and Beijer Ref are strengthening their supply chain capabilities and have committed to the construction of purpose-built facilities at Aware Super and Altis Property Partner’s new South West Sydney industrial estate – Altitude, Bankstown Airport. Owned by Aware Super, one of Australia’s largest superannuation funds, managed by Sydney Metro Airports and developed in partnership with Altis Property Partners, the premier logistics hub’s location at Bankstown Airport enables tenants to take advantage of the prime location and integrate with major infrastructure routes including rail, sea and air freight hubs. Altitude comprises of 162,000 sqm of best in class warehousing and office accommodation across 40-hectares. The industrial estate at Bankstown Airport is the most centrally located warehouse development of this scale with direct access to the M5 motorway, Sydney CBD, Port Botany and the new Western Sydney Airport. Beijer Ref, a global refrigeration and air conditioning wholesaler and OEM, has selected Altitude for its new Australian manufacturing, distribution, and corporate headquarters. Set to be a global showpiece and revolutionise the leading global refrigeration wholesaler’s Australian operation, the purpose-built 22,000 sqm facility has now reached practical completion, with Beijer Ref becoming the first business to move into the new industrial precinct. “Being a part of the complete development process has allowed us to accommodate all aspects of our business and maximise the technology and sustainability opportunities. -

Seasons Greetings!

DECEMBER 2019 Seasons greetings! 2019! A memorable year with the obvious highlight being our In this issue… fabulous new terminal. The photos below tell the story; not just - Photos of terminal project pg 2 the end result, but some of the challenges and disruptions to our operations, businesses and customers throughout this - Eastern Air Services … pg 3 transformation. The project has been heralded a huge success - Airport Billboard pg 4 and, indisputably, this has only been possible due to the commitment and support of the entire team working at the - News from HDFC … pg 5 Airport. On behalf of Council and the Community, I sincerely - AIAC cadets … pg 5 thank each and every individual working at the Airport for their support and professionalism in seamlessly delivering this iconic - HDFC Scholarships… pg 6 project for our community. - Qantas visit and grants… pg 7 Beyond the terminal, 2019 will certainly be remembered for the relentless fires, which have devastated lives and caused significant disruption to the aviation industry. Despite these disruptions, our RPT services are strong, with passenger numbers increasing to 218,000 (Dec 18 to Nov 19). In 2019, Qantas has managed to overcome fleet and crew issues to reach record capacity in the Port Macquarie market in the later part of 2019. Not to be outdone, Virgin Australia has announced a new, overnight service in Port Macquarie from March 2020, in the context of an 2% reduction in overall domestic services. The challenge is set - can we reach record numbers of 230,000 in 2020? Congratulations also to Eastern Air Services in attaining an Air Operator’s Certificate to operate RPT services to Lord Howe Island in 2019. -

NSW Government Submission

Inquiry into Economic Regulation of Airports NSW Government Submission NSW Transport Planning and Landside Access In March 2018, the NSW Government release ‘NSW Future Transport 2056’, a comprehensive strategy to ensure the way we travel is more personal, integrated, accessible, safe, reliable and sustainable. The associated Regional NSW Services and Infrastructure Plan outlines the NSW Government’s thinking on the big trends, issues, services and infrastructure needs which are now shaping, or will soon shape transport in regional NSW. This includes regional aviation, a key component of Transport for NSW’s future vision for the Hub and Spoke model of transport services in NSW that supports the visitor economy by enabling international and domestic visitation. Central to this is the importance of aviation for international, interstate and intrastate movements. Landside Access to Kingsford Smith Airport (Sydney Airport) The NSW Government is upgrading roads around Sydney Airport to help improve traffic flow around the airport and Port Botany. The upgrades are complementing Sydney Airport’s upgrades to its internal road network. The Sydney Airport precinct employs more than 12,000 people. Around half of these people live within public transport, walking or cycling distance of the Airport. Improvements to public transport, walking and cycling connections will improve access for staff and visitors alike. The NSW Government is currently progressing: • The Sydney Gateway project, including major new road linkages between the motorway network and the domestic and international terminals. • Airport Precinct road upgrade projects, with East Precinct works covering Wentworth Avenue, Botany Road, Mill Pond Road, Joyce Drive and General Holmes Drive, Mascot; West Precinct work, in the vicinity of Marsh Street, Arncliffe; and North Precinct work in the vicinity of O’Riordan Street, Mascot. -

Understanding the Protected Airspace for Western Sydney Airport

Understanding the protected airspace for Western Sydney Airport Protecting immediate airspace around airports is essential to ensuring and maintaining a safe operating environment and to provide for future growth. Obstructions in the vicinity of an airport, such as tall structures and exhaust plumes from chimney stacks, have the potential to create air safety hazards and to seriously limit the ability of aircraft arriving and departing from the airport to operate effectively. The protected airspace is known as the Obstacle Limitation Surface (OLS) and has been declared under the provisions of the Commonwealth Airports Act 1996 and Airports (Protection of Airspace) Regulations 1996. What does the OLS do? The OLS is designed to protect aircraft flying in visual conditions in close proximity to the airport. The OLS defines a volume of airspace above a set of surfaces that are primarily modelled upon the layout and configuration of the proposed runways. The surfaces of the OLS extend outward and upward, from ground level at the location of the proposed runways, to a distance of 15 kilometres from the Western Sydney Airport. The OLS components consist of a series of sloping and horizontal surfaces. In the immediate vicinity of the Western Sydney Airport site the surfaces are closer to the ground, an average of 125.5 metres on the Australian Height Datum (AHD). Heights of the OLS components are given above mean sea level, using AHD elevation. For more information contact WSA Co: www.wsaco.com.au | [email protected] Features of the Western Sydney Airport OLS The Western Sydney Airport OLS is based on the long-term runway layout identified in the Airport Plan, consisting of two widely spaced parallel runways of 3,700 metres in length. -

MINUTES AAA Tasmanian Division Meeting AGM

MINUTES AAA Tasmanian Division Meeting AGM 13 September 2019 0830 – 1630 Hobart Airport Chair: Paul Hodgen Attendees: Tom Griffiths, Airports Plus Samantha Leighton, AAA David Brady, CAVOTEC Jason Rainbird, CASA Jeremy Hochman, Downer Callum Bollard, Downer EDI Works Jim Parsons, Fulton Hogan Matt Cocker, Hobart Airport (Deputy Chair) Paul Hodgen, Launceston Airport (Chair) Deborah Stubbs, ISS Security Michael Cullen, Launceston Airport David McNeil, Securitas Transport Aviation Security Australia Michael Burgener, Smiths Detection Dave Race, Devonport Airport, Tas Ports Brent Mace, Tas Ports Rob Morris, To70 Aviation (Australia) Simon Harrod, Vaisala Apologies: Michael Wells, Burnie Airport Sarah Renner, Hobart Airport Ewan Addison, ISS Security Robert Nedelkovski, ISS Security Jason Ryan, JJ Consulting Marcus Lancaster, Launceston Airport Brian Barnewall, Flinders Island Airport 1 1. Introduction from Chair, Apologies, Minutes & Chairman’s Report: The Chair welcomed guests to the meeting and thanked the Hobart team for hosting the previous evenings dinner and for the use of their boardroom today. Smith’s Detection were acknowledged as the AAA Premium Division Meetings Partner. The Chair detailed the significant activity which had occurred at a state level since the last meeting in February. Input from several airports in the region had been made into the regional airfares Senate Inquiry. Outcomes from the Inquiry were regarded as being more political in nature and less “hard-hitting” than the recent WA Senate Inquiry. Input has been made from several airports in the region into submissions to the Productivity Commission hearing into airport charging arrangements. Tasmanian airports had also engaged in a few industry forums and submissions in respect of the impending security screening enhancements and PLAGs introduction. -

Sydney Airport | Sustainability Report 2020

Sustainability Report 2020 From the ground up Sydney Airport | Sustainability Report 2020 Contents Sustainability at Sydney Airport 02 Chair and CEO message 04 Performance highlights 05 Benchmark and ratings performance 06 Our approach to sustainability 06 Contributing to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 07 Global trends 08 Stakeholder engagement 10 Focusing on issues that matter 12 Delivering on our commitments Responsible business 14 Safety 18 Security 19 Business continuity and resilience 21 Operational efficiency and continuous improvement 21 Environmental management 24 Our people 27 Fair and ethical business Planning for the future 28 Building resilience to climate change 34 Sustainable development of the airport 35 Airspace and airfield efficiency 36 Customer experience 37 Access to and from the airport 37 Innovation and technology Supporting our community 39 Fostering strong relationships 39 Community engagement and social impact 42 Reconciliation Action Plan 44 Supporting our partners 45 Economic contribution Performance data 46 General metrics 47 Health, safety and security 48 Environment and climate 49 Customer 50 People and organisation 51 Community investment Other information 53 GRI Index 58 SASB Index 60 Limited assurance statement About this report This 2020 Sustainability Report covers the year 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2020. All financial values are in Australian dollars. This report is prepared in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiative Standards: Core option and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) Standards. The Management Approach for each of our material issues can be found at www. sydneyairport.com.au/corporate/sustainability. The UN Sustainable Development Goals guide our reporting of relevant global issues. -

St Helens Aerodrome Assess Report

MCa Airstrip Feasibility Study Break O’ Day Council Municipal Management Plan December 2013 Part A Technical Planning & Facility Upgrade Reference: 233492-001 Project: St Helens Aerodrome Prepared for: Break Technical Planning and Facility Upgrade O’Day Council Report Revision: 1 16 December 2013 Document Control Record Document prepared by: Aurecon Australia Pty Ltd ABN 54 005 139 873 Aurecon Centre Level 8, 850 Collins Street Docklands VIC 3008 PO Box 23061 Docklands VIC 8012 Australia T +61 3 9975 3333 F +61 3 9975 3444 E [email protected] W aurecongroup.com A person using Aurecon documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version. b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Aurecon. Report Title Technical Planning and Facility Upgrade Report Document ID 233492-001 Project Number 233492-001 File St Helens Aerodrome Concept Planning and Facility Upgrade Repot Rev File Path 0.docx Client Break O’Day Council Client Contact Rev Date Revision Details/Status Prepared by Author Verifier Approver 0 05 April 2013 Draft S.Oakley S.Oakley M.Glenn M. Glenn 1 16 December 2013 Final S.Oakley S.Oakley M.Glenn M. Glenn Current Revision 1 Approval Author Signature SRO Approver Signature MDG Name S.Oakley Name M. Glenn Technical Director - Title Senior Airport Engineer Title Airports Project 233492-001 | File St Helens Aerodrome Concept Planning and Facility Upgrade Repot Rev 1.docx | -

NSW Government Submission March 2018

NSW Government Submission Inquiry into the Operation, Regulation and Funding of Air Route Service Delivery to Rural, Regional and Remote Communities March 2018 1 of 44 Table of Contents: 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 4 2 NSW Government legislative, policy and planning framework .................................... 5 2.1 NSW legislative framework for intrastate air transport routes .................................. 5 2.2 NSW framework for licencing regional aviation ......................................................... 7 2.3 Deregulation of intrastate air service routes .............................................................. 7 2.4 Air space regulation and the use of drones ................................................................ 9 2.5 NSW Government strategic direction for regional transport ................................... 10 2.6 Aviation and regional planning ................................................................................. 11 3 Social and economic impacts of air services ............................................................... 14 3.1 Growing the visitor economy .................................................................................... 14 3.2 Regional development initiatives and regional aviation ........................................... 16 3.3 Importance of regional aviation services for international trade ............................. 17 3.4 Importance of regional aviation services -

Development in the Obstacle Limitation Surface

Development in the Obstacle Limitation Surface Western Sydney Airport’s (WSA) protected airspace is known as the Obstacle Limitation Surface (OLS) and has been declared under the provisions of the Airports Act 1996 (Cth) and Airports (Protection of Airspace) Amendment Regulation 1996. The declaration of the OLS balances the need to ensure a safe operating environment for aircraft with the community’s need for clarity about development surrounding the airport. The OLS is designed to protect aircraft flying in visual conditions in close proximity to the WSA. The OLS defines a volume of airspace above a set of surfaces that are primarily modelled upon the layout and configuration of the confirmed Stage 1 and proposed long-term runways. Further technical information about the OLS is available at www.wsaco.com.au. How does the OLS affect me? The purpose of the OLS is to ensure that development within the OLS area is examined for its impact on future aircraft operations and that it is properly taken into account. The OLS will have no impact on you unless the development you plan on your property infringes on the airport’s protected airspace. You will need to be aware of the OLS if you are planning certain developments on your property. An online tool is available at www.wsaco.com.au where you can search your address to find out the height of the protected airspace above your property. Development that infringes on the airport’s protected airspace is called a controlled activity and can include, but is not limited to: permanent structures, such as buildings, intruding into the protected airspace; temporary structures such as cranes intruding into the protected airspace; or any activities causing intrusions into the protected airspace through glare from artificial light or reflected sunlight, air turbulence from stacks or vents, smoke, dust, steam or other gases or particulate matter. -

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

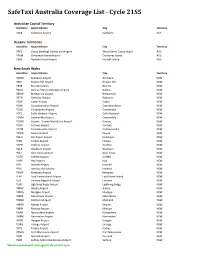

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

Airport Capacity for Sydney

Airport Capacity for Sydney Peter Forsyth, Monash University Expanding Airport Capacity in Large Urban Areas International Transport Forum/OECD 21-22 Feb 2013 1 The Issue… As with other cities, Sydney has a problem of ensuring adequate airport capacity How well has this issue been handled in the past? How well might it be handled in the future? 2 Which Issues are Common With Other Cities? • Clash between economic and environmental aspects • New sites for airports are distant • In some cases, Institutions (eg, Like London’s) • Slots used to ration excess demand • Privatised, like some other airports (eg London's) • Hub issues, connectivity issues • Externalities such as noise and emissions • Will be affected by a possible HST • How to evaluate inbound tourism? 3 In What Ways is Sydney Different? • Light handed regulation- more scope for pricing options • Good evaluation so far? • Evaluation using two techniques - CBA and Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models • Special issues with regional flights • High foreign ownership of airport and airlines poses the question of whose costs and benefits? 4 Agenda History and Background Location, Hubbing, Connectivity and Competition Rationing Excess Demand Evaluation of the Options Externalities Conclusions: Is Sydney a Disaster? 5 Background 6 Facts 1 • Kingsford Smith (KSA) the only RPT airport for Sydney • Canberra 290 km away ( London-Manchester), Newcastle • 8 km from CBD • Coastal site- little room for expansion • Access: car and taxi; expensive railway; bus discontinued (too competitive)