A Postcolonial Theory of Spousal Rape: the Carribean and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lost Women of Iraq: Family-Based Violence During Armed Conflict © Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Rights Group International November 2015

CEASEFIRE centre for civilian rights Miriam Puttick The Lost Women of Iraq: Family-based violence during armed conflict © Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Rights Group International November 2015 Cover photo: This report has been produced as part of the Ceasefire project, a multi-year pro- Kurdish women and men protesting gramme supported by the European Union to implement a system of civilian-led against violence against women march in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, monitoring of human rights abuses in Iraq, focusing in particular on the rights of November 2008. vulnerable civilians including vulnerable women, internally-displaced persons (IDPs), stateless persons, and ethnic or religious minorities, and to assess the feasibility of © Shwan Mohammed/AFP/Getty Images extending civilian-led monitoring to other country situations. This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the publishers and can un- der no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is a new initiative to develop ‘civilian-led monitoring’ of violations of international humanitarian law or human rights, to pursue legal and political accountability for those responsible for such violations, and to develop the practice of civilian rights. The Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights is registered as a charity and a company limited by guarantee under English law; charity no: 1160083, company no: 9069133. Minority Rights Group International MRG is an NGO working to secure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation and understanding between communities. -

Domestic Violence in Legal Education and Legal Practice: a Dialogue Between Professors and Practitioners Stacy Caplow Brooklyn Law School, [email protected]

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship 2003 Domestic Violence in Legal Education and Legal Practice: A Dialogue Between Professors and Practitioners Stacy Caplow Brooklyn Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation 11 J. L & Pol'y 409 (2002-2003) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN LEGAL EDUCATION AND LEGAL PRACTICE: A DIALOGUE BETWEEN PROFESSORS AND PRACTITIONERS* PANELISTS** KRISTIN BEBELAAR is an Associate with Gulielmetti & Gesmer, P.C., where she practices family law, real estate law, and general civil litigation. Prior to law school, she was the Children's Program Coordinator at La Casa de las Madres, a San Francisco shelter for battered women, and she later worked in a special project of the San Francisco District Attorney's Office to improve child sexual abuse investigations. She graduated from Brooklyn Law School in 1996. After law school, she worked as a staff attorney at the HIV Project of South Brooklyn Legal Services, where she represented low-income, HIV-positive clients in family, housing, health, discrimination and estate law matters. STACY CAPLOW is Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School and the Director of the Law School's Clinical Education Program. Since 1976, she has taught diverse clinics at Brooklyn * This article is a transcription of a program held at Brooklyn Law School on April 15, 2002. The event was sponsored and coordinated by Brooklyn Law Students Against Domestic Violence (BLSADV), a feminist student organization at Brooklyn Law School, to address the importance of incorporating gender issues, including domestic violence, into law school curriculum. -

She Is Not a Criminal

SHE IS NOT A CRIMINAL THE IMPACT OF IRELAND’S ABORTION LAW Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: EUR 29/1597/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Stock image: Female patient sitting on a hospital bed. © Corbis amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Executive summary ................................................................................................... 6 -

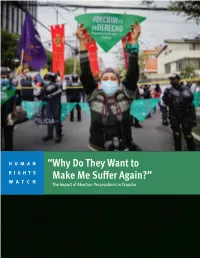

“Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” the Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador

HUMAN “Why Do They Want to RIGHTS WATCH Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 8 To the Presidency ................................................................................................................... -

Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #Metoo

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 49 Issue 1 Article 3 2019 Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #MeToo Nicole Hallett University of Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hallett, Nicole (2019) "Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #MeToo," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 49 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol49/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMMIGRANT WOMEN IN THE SHADOW OF #METOO Nicole Hallett* I. INTRODUCTION We hear Daniela Contreras’s voice, but we do not see her face in the video in which she recounts being raped by an employer at the age of sixteen.1 In the video, one of four released by a #MeToo advocacy group, Daniela speaks in Spanish about the power dynamic that led her to remain silent about her rape: I couldn’t believe that a man would go after a little girl. That a man would take advantage because he knew I wouldn’t say a word because I couldn’t speak the language. Because he knew I needed the money. Because he felt like he had the power. And that is why I kept quiet.2 Daniela’s story is unusual, not because she is an undocumented immigrant who was victimized -

Supplementary Information on Kenya, Scheduled for Review by the Pre

Re: Supplementary Information on Kenya, Scheduled for Review by the Pre-sessional Working Group of the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights during its 56th Session Distinguished Committee Members, This letter is intended to supplement the periodic report submitted by the government of Kenya, which is scheduled to be reviewed during the 56th pre-session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (the Committee). The Center for Reproductive Rights (the Center) a global legal advocacy organization with headquarters in New York and, and regional offices in Nairobi, Bogotá, Kathmandu, Geneva, and Washington, D.C., hopes to further the work of the Committee by providing independent information concerning the rights protected under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR),1 and other international and regional human rights instruments which Kenya has ratified.2 The letter provides supplemental information on the following issues of concern regarding the sexual and reproductive rights of Kenyan women and girls: the high rate of preventable maternal mortality and morbidity; the abuse and mistreatment of women that attend maternal health care services; inaccessibility of safe abortion services and post-abortion care; lack of access to comprehensive family planning services and information; and discrimination resulting in gender-based violence and female genital mutilation. I. The Right to Equality and Non-Discrimination It has long been recognized that the obligation to ensure the rights -

STOP Violence Against Women Project Evaluation FY99

West Virginia STOP Violence Against Women Project Evaluation FY99 Provided by the Department of Military Affairs and Public Safety Division of Criminal Justice Services Criminal Justice Statistical Analysis Center January 2002 1204 Kanawha Boulevard, East Charleston, WV 25301 (304) 558-8814 www.wvdcjs.com J. Norbert Federspiel, Director Michael Cutlip, Deputy Director-Programs Laura Hutzel, CJSAC Director Tonia Thomas, Justice Programs Specialist Lora Maynard, Justice Programs Specialist Fiscal Year 1999 Project Year July 2000 - June 2001 Evaluation Conducted and Written by: Beth Morrison, Consultant Statistical Summary Analyzed and Written by: Erica Turley, Research Analyst This project was supported by grant #99-VAW-022 awarded by the Violence Against Women Office, Office of Justice Programs through the Division of Criminal Justice Services. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this evaluation are those of the authors and may not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Department of Justice of the State of West Virginia. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................ 3 Division of Criminal Justice Services.............................................................. 4 Grants Awarded and Funds Expended ........................................................... 5 Grant Purposes and Progress ......................................................................... 6 Randolph County STOP Team ................................................................................. -

Privacy and Domestic Violence in Court

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 16 (2009-2010) Issue 2 William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law: 2009 Symposium: From the Courtroom Article 2 to the Mother's Womb: Protecting Women's Privacy in the Most Important Places February 2010 Privacy and Domestic Violence in Court Rebecca Green William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons Repository Citation Rebecca Green, Privacy and Domestic Violence in Court, 16 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 237 (2010), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol16/iss2/2 Copyright c 2010 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl PRIVACY AND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE IN COURT REBECCA HULSE* INTRODUCTION I. SITUATING “PRIVACY” IN THE DOMESTIC VIOLENCE CONTEXT A. The Public-Private Distinction B. The Problem of “Privacy” 1. Defining Privacy 2. Feminist Legal Thought: Interpreting Privacy C. Privacy and Domestic Violence in Court II. PUBLIC ACCESS TO COURT PROCEEDINGS AND RECORDS: GENERAL OVERVIEW A. The Presumption of Openness B. Presumption Limited 1. At the Discretion of the Judge 2. At the Discretion of the State Legislature or the Court 3. The Impact of the Internet III. DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND THE ACCESS-VERSUS-PRIVACY TENSION A. Domestic Violence Cases: Public Access B. Online Access to Domestic Violence Records C. Specialized Domestic Violence Courts, Privacy, and Access 1. Overview 2. Specialized Domestic Violence Courts and Public Access a. -

Egypt: Situation Report on Violence Against Women

» EGYPT Situation report on Violence against Women 1. Legislative Framework The Egyptian constitution adopted in 2014 makes reference to non-discrimination and equal opportunities (article 9, 11 and 53). Article 11 is the only article that mentions violence against women, stating that: “…The State shall protect women against all forms of violence and ensure enabling women to strike a balance between family duties and work requirements…”. Article 11 states the right of women to political representation as well as equality between men and women in civil, political, economic, social and cultural matters. Article 53 prohibits discrimination on the basis of gender, and makes the state responsible for taking all necessary measures to eliminate all forms of discrimination. Egypt has ratified the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), although with reservations to Article 2 on policy measures and Articles 16 regarding marriage and family life and article 29 . The reservation to Article 9 concerning women’s right to nationality and to pass on their nationality to their children was lifted in 2008. Egypt has signed but not ratified the Rome Statute on the ICC and is not yet a party to the Council of Europe Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women. Articles 267, 268, 269 and 289 of the penal code relating to crimes of rape, sexual assault and harassment fail to address the wave of sexual assault and rape in Egypt following the 2011 revolution. For instance, article 267 of the penal code defines rape as penile penetration of the vagina and does not include rape by fingers, tools or sharp objects, oral or anal rape. -

Creating a Domestic Violence Drug Court

The Scholar: St. Mary's Law Review on Race and Social Justice Volume 22 Number 2 Article 2 5-2020 Lessons Learned, Lessons Offered: Creating a Domestic Violence Drug Court Judge Rosie Speedlin Gonzalez Bexar County Court at Law #13 Dr. Stacy Speedlin Gonzalez The University of Texas at San Antonio Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/thescholar Part of the Counseling Commons, Counseling Psychology Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence Commons, Family Law Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Judges Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal Remedies Commons, Legislation Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Judge Rosie Speedlin Gonzalez & Dr. Stacy Speedlin Gonzalez, Lessons Learned, Lessons Offered: Creating a Domestic Violence Drug Court, 22 THE SCHOLAR 221 (2020). Available at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/thescholar/vol22/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the St. Mary's Law Journals at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Scholar: St. Mary's Law Review on Race and Social Justice by an authorized editor of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Speedlin Gonzalez and Speedlin Gonzalez: Creating a Domestic Violence Drug Court LESSONS LEARNED, LESSONS OFFERED: CREATING A DOMESTIC VIOLENCE DRUG COURT JUDGE ROSIE SPEEDLIN GONZALEZ* & DR. STACY SPEEDLIN GONZALEZ INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 222 I. DOMESTIC VIOLENCE: STATISTICAL INFORMATION .................... 224 A. Systemic Issues That Perpetuate Domestic Violence ........ -

Marital Rape: Sacrosanct Or Covenant

Vol. 5(1), pp. 1-5, January 2017 DOI: 10.14662/IJELC2016.074 International Journal of English Copy© right 2017 Literature and Culture Author(s) retain the copyright of this article ISSN: 2360-7831 http://www.academicresearchjournals.org/IJELC/Index.htm Research Paper Marital rape: Sacrosanct or Covenant Atul Ratna (B.A. LLB 13) . E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 30 December 2016 “Marriage is a mosaic you build with your spouse. Millions of tiny moments create your love story”. -Jennifer Smith As a Girl grows and turns to a women among a lot of duty like taking care of the family and doing the household chores the Indian Society also demands her to get married; become someone’s wife to justify her life as a virtuous women. Marriage in India is done with or without the consent of the Girl. Completely ignoring the fact whether or not the Girl is ready mentally and physically to fulfil the marital obligation. The point of Dismay also lies in the fact that Most of the Men fail to understand the Depth of Marriage as an Institution and look upon their wives as objects to fulfil their Sexual needs. As a result the marriage loses its sanctity as a bond of love and togetherness and a woman loses her dignity to her husband in order to complete her duty as a wife. Marital Rape is basically the sexual intercourse which is forced by the Husband over his wife even when she is not willing to do the same. Marital Rape is mostly accompanied by Domestic violence and mental cruelty. -

Marital Rape: a Higher Standard Is in Order

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 1 (1994) Issue 1 William & Mary Journal of Women and Article 8 the Law October 1994 Marital Rape: A Higher Standard Is in Order Linda Jackson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Linda Jackson, Marital Rape: A Higher Standard Is in Order, 1 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 183 (1994), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol1/iss1/8 Copyright c 1994 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl MARITAL RAPE: A HIGHER STANDARD IS IN ORDER LINDA JACKSON* Marriage is the only actual bondage known to our law. There remain no legal slaves, except the mistress of every house.1 ... [H]owever brutal a tyrant she may be unfortunately chained to ... [her husband] can claim from her and enforce the lowest degradation of a human being, that of being made the instru- ment of an animal function contrary to her inclinations.2 John Stuart Mill It is very little to me to have the right to vote, to own property, etc., if I may not keep my body, and its uses, in my absolute right. Not one wife in a thousand can do that now.3 Lucy Stone Women, particularly married women, have advanced a great deal since the time of John Stuart Mill and Lucy Stone.4 Mill and Stone's concerns regarding marital rape, however, are jus- tified even today.