Tracking the Ancient Technique of Jamdani from South-Uppada in East Godavari District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAP:East Godavari(Andhra Pradesh)

81°0'0"E 81°10'0"E 81°20'0"E 81°30'0"E 81°40'0"E 81°50'0"E 82°0'0"E 82°10'0"E 82°20'0"E 82°30'0"E EAST GODAVARI DISTRICT GEOGRAPHICAL AREA (ANDHRA PRADESH) 47 MALKANGIRI SH Towards Sileru 18°0'0"N 18°0'0"N IR (EXCLUDING: AREA ALREADY AUTHORISED) ERVO I RES AY AR NK DO MALKANGIRI V IS H KEY MAP A K H A P A T N A M M Towards Polluru CA-02 A CA-01 M M ± A CA-07 H CA-35 CA-34 K V CA-60 I CA-03 CA-57 CA-58 S CA-33 CA-59 H CA-04 CA-57 CA-37 CA-36 AKH 17°50'0"N CA-32 CA-56 17°50'0"N CA-31 CA-55 CA-05 CA-38 CA-55 CA-39 AP CA-06 CA-30 CA-53 CA-54 CA-40 CA-39 A CA-07 CA-29 CA-41 CA-51 T CA-08 CA-41 T NAM CA-07 CA-28 CA-51 oward CA-42 CA-52 CA-27 CA-51 CA-09 CA-26 CA-44 CA-44 CA-25 s Tu T CA-10 CA-11 CA-43 CA-45 CA-46 o L lasipaka w W CA-24 A ar E CA-12 CA-23 S NG T CA-13 E d G CA-47 CA-22 B s O CA-48 D CA-21 F K A CA-14 CA-50 O V CA-20 o A R CA-49 Y. -

Central Water Commission Daily Flood Situation Report Cum Advisories 15-08-2020 1.0 IMD Information 1.1 1.1 Basin Wise Departure

Central Water Commission Daily Flood Situation Report cum Advisories 15-08-2020 1.0 IMD information 1.1 1.1 Basin wise departure from normal of cumulative and daily rainfall Large Excess Excess Normal Deficient Large Deficient No Data No [60% or more] [20% to 59%] [-19% to 19%) [-59% to -20%] [-99% to -60%] [-100%) Rain Notes: a) Small figures indicate actual rainfall (mm), while bold figures indicate Normal rainfall (mm) b) Percentage departures of rainfall are shown in brackets. th 1.2 Rainfall forecast for next 5 days issued on 15 August 2020 (Midday) by IMD 2.0 CWC inferences 2.1 Flood Situation on 15th August 2020 2.1.1 Summary of Flood Situation as per CWC Flood Forecasting Network On 15th August 2020, 27 Stations (16 in Bihar, 5 in Assam, 4 in Uttar Pradesh,1 each in Jharkhand and West Bengal) are flowing in Severe Flood Situation and 28 stations (11 in Bihar, 8 in Assam, 5 in Uttar Pradesh, 2 in Andhra Pradesh,1 each in Arunachal Pradesh and Telangana) are flowing in Above Normal Flood Situation. Inflow Forecast has been issued for 37 Barrages and Dams (11 in Karnataka, 4 in Madhya Pradesh, 3 each in Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Tamilnadu, 2 each in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Telangana & West Bengal and 1 each in Odisha & Jharkhand) Details can be seen in link http://cwc.gov.in/sites/default/files/dfb202015082020_5.pdf 2.1.1 Summary of Flood Situation as per CWC Flood Forecasting Network 2.2 CWC Advisories • Scattered to Fairly widespread rainfall very likely over northwest India during next 5 days. -

Synopsis of Debate

RAJYA SABHA _________ ∗SYNOPSIS OF DEBATE _________ (Proceedings other than Questions and Answers) _________ Monday, July 14, 2014/Ashadha 23, 1936 (Saka) ________ STATEMENT BY MINISTER ♣Alleged Destruction of more than 1.5 lakh files in the Ministry of Home Affairs - Contd. The Minister of Home Affairs (SHRI RAJNATH SINGH), replying to the points raised by the Members, said: I have no objection regarding any question. I have already made it clear that no file related to Mahatama Gandhi, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri or Lord Mountbatten has been destroyed. As Home Minister of Government of India, I wish to assure all of you that BJP would not allow disruption in the continuity of the history at any cost. Nobody can deny the contribution of the Father of Nation, Mahatama Gandhi. Mahatama Gandhi is the most respected global personality of our country. Therefore, do not doubt us. I have already given the clarification regarding the files related to the assassination of Gandhiji. This is not the case that files were only destroyed after our Government came to the power. Files were also destroyed when UPA Government was in power. Some categorised files are only destroyed as per Manual of Office Procedure. Opening and destroying of the file is done under a continuous process. When actions on the files are over, they are ∗This Synopsis is not an authoritative record of the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha. ♣ Made on 11th July, 2014. 65 categorized in three categories. Files of historical importance are kept into a complete safe custody even after their microfilming. -

State and Non-State Marine Fisheries Management: Legal Pluralism in East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh, India

STATE AND NON-STATE MARINE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT: LEGAL PLURALISM IN EAST GODAVARI DISTRICT, ANDHRA PRADESH, INDIA …. Sarah Southwold-Llewellyn Rural Development Sociology Department of Social Sciences Wageningen University Wageningen, The Netherlands [email protected] [email protected] Sarah Southwold-Llewellyn, 2010 Key words: marine fisheries, traditional fishing, mechanised fishing, management, legal pluralism, East Godavari District This 2010 report is a revision of an earlier working paper, Cooperation in the context of crisis: Public-private management of marine fisheries in East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh, India. IDPAD Working Paper No. 4. IDPAD: New Delhi and IDPAD: The Hague, 2006 (www. IDPAD.org). The Project, Co-operation in a Context of Crisis: Public-Private Management of Marine Fisheries in South Asia, was part of the fifth phase of the Indo-Dutch Programme for Alternative Development (2003-2006). IDPAD India Secretariat: Indian Institute of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi IDPAD The Netherlands secretariat: Netherlands Foundation for the Advancement of Tropical Research (WOTRO), The Hague, The Netherlands 2 Acknowledgements My research in East Godavari District would not have been possible without the cooperation and help of many more than I can acknowledge here. The help of many Government officers is greatly appreciated. On the whole, I was impressed by their professionalism, commitment and concern. They gave me their valuable time; and most of them were extremely candid. Much that they told me was ‘off the record’. I have tried to protect their anonymity by normally not citing them by name in the report. There are far too many to individuals to mention them all. -

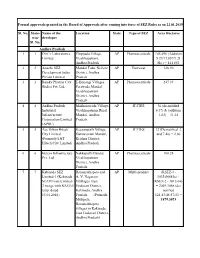

Wise Sl. No. Name of the Developer Location State Type of SEZ Area

Formal approvals granted in the Board of Approvals after coming into force of SEZ Rules as on 22.01.2019 Sl. No. State- Name of the Location State Type of SEZ Area Hectares wise developer Sl. No. Andhra Pradesh 1 1 Divi’s Laboratories Chippada Village, AP Pharmaceuticals 105.496 (Addition Limited Visakhapatnam, 9.29/17.857/9.21 Andhra Pradesh Ha.) = 141.853 2 2 Apache SEZ Mandal Tada, Nellore AP Footwear 126.90 Development India District, Andhra Private Limited Pradesh 3 3 Ramky Pharma City E-Bonangi Villages, AP Pharmaceuticals 247.39 (India) Pvt. Ltd. Parawada Mandal, Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 4 4 Andhra Pradesh Madhurawada Village, AP IT/ITES 36 (de-notified Industrial Visakhapatnam Rural 6.37) & (addition Infrastructure Mandal, Andhra 1.62) = 31.25 Corporation Limited Pradesh (APIIC) 5 5 Ace Urban Hitech Keesarapalli Village, AP IT/ITES 12 (De-notified 2 City Limited Gannavaram Mandal, and 7.40) = 2.60 (Formerly L&T Krishna District, Hitech City Limited) Andhra Pradesh 6 6 Hetero Infrastructure Nakkapalli Mandal, AP Pharmaceuticals 100.28 Pvt. Ltd. Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 7 7 Kakinada SEZ Ramanakkapeta and AP Multi-product (KSEZ-1 - Limited-1 (Kakinada A. V. Nagaram 1035.6688 ha + SEZ Private Limited- Vikllages, East KSEZ-2 - 1013.64) 2 merge with KSEZ-1 Godavari District, = 2049.3088 (de- letter dated Kakinada, Andhra notified 13.01.2016) Pradesh (Ponnada, 121.43/48.5715) = Mulapeta, 1879.3073 Ramanakkapeta villages in Kakinada, East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh) 8 8 Andhra Pradesh Atchutapuram and AP Multi Product 1300.82 (2206.03 - Industrial Rambilli Mandals, 905.21 denotified Infrastructural Visakhapatnam in the BOA Corporation District, Andhra meeting on Ltd.(APIIC) Pradesh 14.09.2012 9 9 Whitefield Paper Tallapudi Mandal, AP Writing & Printing 109.81 Mills Ltd. -

Andhra Pradesh, Indian East Coast

Andhra Pradesh, Indian East Coast V Sree Krishna Consultant-Environment/BOBP Marine Habitats Mangroves Algae Fisheries Marine Pollution Industries Agriculture Exploitation of natural resources References Appendices Institutions engaged in environmental research, monitoring and enforcement Legislation against threats to the marine environment. Other publications on the marine environment. ( 170 ) 47. MARINE HABITATS 47.1 Mangroves The total mangrove area in India has been estimated at 6740 km2. Of this, Andhra Pradesh has about 9 per cent, an area of 582 km2. The greater part of the mangrove forests in Andhra Pradesh are in rhe Krishna and Godavari River estuaries (see Figure 32 on next page). To protect these unique forests, the Andhra Pradesh Government has formed two sanctuaries. The Coringa Wildlife Sanctuary in East Godavari District, was established in 1978, while the Krishna Sanctuary in Nagayalanka, Vijayawada, was inaugurated more recently. The mangroves of Andhra Pradesh are mainly Auicennia. A clear felling system is being practised, on a 25-year rotation basis in Coringa, and every 15 years in Kandikuppu (both in East Godavari). The Krishna mangroves are also managed on a 25-year rotation felling system. Before the abolition of private estates came into Areas notified as mangrove forest blocks force, and the subsequent grouping of the region’s mangroves into forest blocks (see table District Name of rho forest block Area in ha alongside), most of the mangrove areas in East Godavari were under the control of private estate East Godavari owners, who heavily exploited them. The mangrove areas were further degraded by Kakinada Tq. Kegita R.F. 467 indiscriminate felling and grazing. -

Government of India Ministry of Tourism Lok Sabha

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF TOURISM LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.4575 ANSWERED ON 22.07.2019 DEVELOPMENT OF HOPE ISLAND IN ANDHRA PRADESH 4575. SHRIMATI VANGA GEETHA VISWANATH: Will the Minister of TOURISM be pleased to state: (a) whether the Government proposes to develop Hope Island in Kakinada, East Godavari district in Andhra Pradesh, Konaseema Circuit and Akhand Godavari under PRASAD scheme, Coastal tourism development circuits in Nellore District, setting up of restaurants with 7, 5 & 3 star hotels around Polavaram Projects to attract tourists; (b) if so, the details thereof and present status of each project in Andhra Pradesh; (c) the funds released/spent on each said project in Andhra Pradesh; and (d) the reasons for snail’s pace of work on the Hope Island Circuit in Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh? ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE FOR TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) (SHRI PRAHLAD SINGH PATEL) (a) to (d): The Ministry of Tourism, under the Swadesh Darshan Scheme provides Central Financial Assistance to State Governments/Union Territory (UT) Administrations for development of thematic tourist circuits in the country, with the objective of improving connectivity and infrastructure of tourism destinations to enrich overall tourist experience, enhance livelihood and employment opportunities and to attract domestic as well as foreign tourists to the destinations. The projects for development are identified in consultation with the State Governments/UT Administrations and are sanctioned subject to submission of project proposals, their adherence to relevant scheme guidelines, submission of suitable detailed project reports, availability of funds and utilization of funds released earlier. Based on the above, the Ministry has sanctioned the following projects to the State of Andhra Pradesh – (Rs. -

District Census Handbook, East Godavari, Part X

CENSUS 1971 SERIES 2 ANDHRA PRADESH DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK EAST GODA V ARt PART X-A VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY PART X-B VILLAGE & TOWN PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT T. VEDANTAM Of THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS ANDHRA PRADESH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH 1973 Rajahmundry had been in the 'News' e,ven btrl'iJl-c this saw mill unit started producing the "Gossip Bench". 3. There is g~od d~mand tor the wooden furniture pre jJared at thiS umt. The Indian Navy the P 'J T V' I ' 01 ru,~ts at lsak tapatnam and Madras, the Housing BOa1ds of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu th H O 1 lh Si 0 b 01 ' C In l us .an, up Ul ding yard at Visakhapatnam, Central and State Warehousing Corporations, Post and Tele graph; and Defence Departments figure prominently among the major consumers of the mill's products. 40 The volume of business transacted between the yea) 196-1·65 and 1970-71 indicates the stupendous gTOwth made by this unique concern during a short span of about 6 years. The turnover in the three main divisions of th~ unit viz., Sawing, Pmcessing and Treatment whzch stood in the order of 13 ,600 c.tt., 600 c.ft. and 3iOO c.ft.} valued totally at Rs. 2.6 lakhs in 1964-65 increased to 2,65,000c.ft., 14}OO c.ft. and THE INTEGRATED SAW MILL UNIT, 68,~QO c.~t. valued at over Rs. 21 lakhs in 1970-71. RAJAHMUNDRY Thz~ umt. with countrywide fame is looked upon as a pwneerznfj p~oject in the field of country wood The motif on the, cover page depicts a fully manufactunng zndustry. -

(DTC) District Tourism Council, East Godavari Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh

Invitation: Expression of Interest for Development of Perugu Lanka opposite to Gowthami Ghat in the River Godavari, Rajamahendravaram, A.P. District Collector & Chairman (D.T.C) District Tourism Council, East Godavari Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh. Invitation: Expression of Interest for Development of Perugu Lanka in the River Godavari, Rajamahendravaram, A.P Contents 1. TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN ANDHRA PRADESH ... .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 2. ABOUT PERUGU LANKA 2.1. ROAD CONNECTIVITY 2.2. RAIL CONNECTIVITY 2.3. AIR CONNECTIVITY 3. NEARBY TOURIST ATTRACTIONS 3.1. PAPI HILLS 3.2. GODAVARI BRIDGES 3.3. ISKCON TEMPLE 3.4. SIR ARTHUR COTTON MUSEUM 3.5. KADIYAPULANKA NURSERIES 4. PURPOSE OF EXPRESSION OF INTEREST 5. EXPRESSION OF INTEREST 6. SCHEDULE OF SUBMISSION OF E.O.I 7. SUBMISSION OF EOI Annexure 1: Letter of application Annexure 2: Applicant details Annexure 3: Net worth certificate Annexure 4: Development Plan for the Project Annexure 5: Power of attorney for authorized signatory Annexure 6: Site Photographs Invitation: Expression of Interest for Development of Perugu Lanka in the River Godavari, Rajamahendravaram, A.P DISCLAIMER This Expression of Interest (E.o.I) document has been prepared with adequate care. However, the participant should verify that the document is complete in all respects. Intimation of discrepancy, if any should be given to the Collector & Chairman (DTC), East Godavari District, Kakinada at below mentioned address: To The Collector & Chairman (D.T.C), East Godavari District, Kakinada, A.P Email: [email protected], Contact: 9121144076 Neither, A.P.T.A or District Tourism Committee, East Godavari District, Kakinada nor its employees or consultants will have any liability to any prospective applicant or any other person under the law of contract, for any loss, expense or damage which may arise from or incurred or suffered in connection with anything contained in this EOI document. -

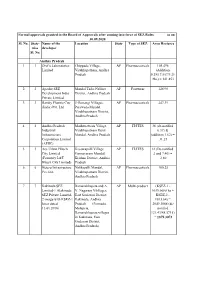

Wise Sl. No. Name of the Developer Location State Type of SEZ Area

Formal approvals granted in the Board of Approvals after coming into force of SEZ Rules as on 30.09.2020 Sl. No. State- Name of the Location State Type of SEZ Area Hectares wise developer Sl. No. Andhra Pradesh 1 1 Divi’s Laboratories Chippada Village, AP Pharmaceuticals 105.496 Limited Visakhapatnam, Andhra (Addition Pradesh 9.29/17.857/9.21 Ha.) = 141.853 2 2 Apache SEZ Mandal Tada, Nellore AP Footwear 126.90 Development India District, Andhra Pradesh Private Limited 3 3 Ramky Pharma City E-Bonangi Villages, AP Pharmaceuticals 247.39 (India) Pvt. Ltd. Parawada Mandal, Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 4 4 Andhra Pradesh Madhurawada Village, AP IT/ITES 36 (de-notified Industrial Visakhapatnam Rural 6.37) & Infrastructure Mandal, Andhra Pradesh (addition 1.62) = Corporation Limited 31.25 (APIIC) 5 5 Ace Urban Hitech Keesarapalli Village, AP IT/ITES 12 (De-notified City Limited Gannavaram Mandal, 2 and 7.40) = (Formerly L&T Krishna District, Andhra 2.60 Hitech City Limited) Pradesh 6 6 Hetero Infrastructure Nakkapalli Mandal, AP Pharmaceuticals 100.28 Pvt. Ltd. Visakhapatnam District, Andhra Pradesh 7 7 Kakinada SEZ Ramanakkapeta and A. AP Multi-product (KSEZ-1 - Limited-1 (Kakinada V. Nagaram Vikllages, 1035.6688 ha + SEZ Private Limited- East Godavari District, KSEZ-2 - 2 merge with KSEZ-1 Kakinada, Andhra 1013.64) = letter dated Pradesh (Ponnada, 2049.3088 (de- 13.01.2016) Mulapeta, notified Ramanakkapeta villages 121.43/48.5715) in Kakinada, East = 1879.3073 Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh) 8 8 Andhra Pradesh Atchutapuram and AP Multi Product 2206.03 (de- Industrial Rambilli Mandals, notified 905.21 Infrastructural Visakhapatnam District, & 518.22) = Corporation Andhra Pradesh 782.60 Ltd.(APIIC) 9 9 Whitefield Paper Tallapudi Mandal, West AP Writing & 109.81 Mills Ltd. -

List of SBI Branches Autorised to Conduct SBFTC Business Sl.No. Br

List of SBI Branches autorised to conduct SBFTC Business Sl.No. Br Code Branch Name Circle / Vertical State City Add1 Add2 Add3 Postal code STD CODE Land line Number e-mail ID 1 SBI00156 PORT BLAIR KOLKATA ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR SOUTH ANDAMAN MOHANPURA ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS PORTBLAIR 744101 3192 236638 [email protected] 2 SBI00578 PATAMATA SME BR. VIJAYAWADA AMARAVATI ANDHRA PRADESH KRISHNA MG RD,PATAMATA,NR AUTONAGAR GATE VIJAYA DIST:KRISHNA ANDHRA PRADESH 520007 8660 2555704 [email protected] 3 SBI00836 ELURU AMARAVATI ANDHRA PRADESH WEST GODAVARI P.B.NO.213, N R PET,ELURU DIST:WEST GODAVARI ANDHRA PRADESH 534006 88120 242025 [email protected] 4 SBI00844 GUNTUR AMARAVATI ANDHRA PRADESH GUNTUR KANNAVARI THOTA GUNTUR DISTRICT ANDHRA PRADESH 522004 863 2218199 [email protected] 5 SBI00874 MASULIPATNAM AMARAVATI ANDHRA PRADESH KRISHNA AMBEDKAR X RD,LAXMI TAKIES CENTRE KRISHNA DIST ANDHRA PRADESH 521002 8672 251093 [email protected] 6 SBI00925 TANUKU AMARAVATI ANDHRA PRADESH WEST GODAVARI DNO25-13-17/1,YERRAMILLI STREET,TANUKU DIST:WEST GODAVARI ANDHRA PRADESH 534211 8819 222147 [email protected] 7 SBI00933 TIRUPATI AMARAVATI ANDHRA PRADESH CHITTOOR P B NO.8,BEHIND GOVINDARAJA SWAMY TEMPL TIRUPATHI, CHITTOOR ANDHRA PRADESH. 517501 877 2254090 [email protected] 8 SBI00952 VISAKHAPATNAM AMARAVATI ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM REDNAM GARDENS, JAIL RAOD JUNCTION OPP.PAGES/VODAPHONE OFF, VISAKHAPATNAM ANDHRA PRADESH 530002 891 2564865 [email protected] 9 SBI01163 NELLORE TOWN BRANCH AMARAVATI ANDHRA PRADESH NELLORE POST BOX NO.49, -

EAST GODAVARI DISTRICT 2764 PLANNING Oomtlssion LIBRARY : 9?£ M CONTENTS

DISTRICT PLAN 1957—5jB, EAST GODAVARI DISTRICT 2764 PLANNING OOMtlSSION LIBRARY : 9?£ M CONTENTS PAGE. PBEFACE. FRONT PAGE. PART-I GEMEEAL 1 AN (OUTLINE OFTHE STATE’S SECOND YEAR PIROGRAMME OF SECOND PLAN 13 PART-II PROGRAMMES OF DEVELOPMENT AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION 21 MINOR IRRIGATION 37 jLAMD DEVELOPMENT 38 ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 39 FORESTS 43 FISHERIES 44 CO-OPERATION 47 WAREHOUSING AND MARKETING 52 NATIONAL EXTENSION SERVICE AND COMMUNITY PROJECTS 55 DISTRICT MAP POWER 57 MAJOR AND MEDIUM INDUSTRIES 57 VILLAGE AND SMALL SCALE INDUSTRIES 58 ROADS 66 EDUCATION 96 11 MEDICAL 75 PUBLIC HEALTH 78 HOUSING 79 LABOUR & LABOUR WELFARE WELFARE OF BACKWARD CLASSES AND SCHEDULED CASTES 82 WELFARE OF SCHEDULED TRIBES 88 WOMEN WELFARE 101 SOCIAL WELFARE 101 MUNICIPAL ROADS AND DEVELOPMENT WORKS 102 BROADCASTING 103 PUBLICITY 104 POST AND TELEGRAPHS 104 RAILWAYS 104 LIST OF. MEMBERS OF DISTRICT PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE 106 PREFACE. The District is in a way the pivot of the whole Structure of Planning. At that level plans from different sectors come intimately into the life of the people. It was there fore considered necessary to draft and publish the district plans. The District plans for the year 1959-57 were accordingly publish ed for the 11 districts of the former Andhra State. A similar attempt has been made to work out the plans of all the 20 districts of Andhra Pradesh for the year 1957-58. The book is divided into 2 parts ; Part I gives some general statistical information pertaining to the district together with a brief account of the State’s Second year pro gramme under the Plan and Part II gives the detailed programmes of development works.