Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Papua New Guinea: Birding Attenborough’S Paradise

PAPUA NEW GUINEA: BIRDING ATTENBOROUGH’S PARADISE 17 AUGUST – 03 SEPTEMBER 2021 17 AUGUST – 03 SEPTEMBER 2022 17 AUGUST – 03 SEPTEMBER 2023 Raggiana Bird-of-paradise is one of our major targets on this trip (photo Matt Prophet). www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Papua New Guinea: Birding Attenborough’s Paradise Papua New Guinea (PNG) is undoubtedly a birder’s paradise. Thirty-four birds-of-paradise (BoPs) live on the island of New Guinea, of which 31 can be found in PNG, and a large number of these are possible on this tour – get ready for sensory overload! The island is home to approximately 400 endemic bird species. Together with awe-inspiring scenery, endless rainforests, and fascinating highland societies that only made contact with the outside world in the 1930s, this makes PNG a definite must-see destination for any avid birder and nature enthusiast. We start our adventure in the tropical savanna near Port Moresby. This area holds species restricted to northern Australia and PNG, such as the remarkable and huge Papuan Frogmouth, the localized Fawn-breasted Bowerbird, and several gorgeous kingfishers such as Blue-winged Kookaburra, Yellow-billed Kingfisher, and Brown-headed Paradise Kingfisher. We will fly to the Mount Hagen Highlands, where we base ourselves at Kumul Lodge, the holy grail of PNG highland birding. At Kumul's legendary feeding table some of PNG’s most spectacular birds await us in the form of Ribbon-tailed Astrapia (surely one of the best-looking of the island's birds-of-paradise?), Brehm's Tiger Parrot, Archbold's Bowerbird, Crested Satinbird, and more. -

Perú: Cordillera Escalera-Loreto Perú: Cordillera Escalera-Loreto Escalera-Loreto Cordillera Perú: Instituciones Participantes/ Participating Institutions

.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................no. 26 ....................................................................................................................... 26 Perú: Cordillera Escalera-Loreto Perú: Cordillera Escalera-Loreto Instituciones participantes/ Participating Institutions The Field Museum Nature and Culture International (NCI) Federación de Comunidades Nativas Chayahuita (FECONACHA) Organización Shawi del Yanayacu y Alto Paranapura (OSHAYAAP) Municipalidad Distrital de Balsapuerto Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana (IIAP) Herbario Amazonense de la Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana (AMAZ) Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Centro -

Ornithological Surveys in Serranía De Los Churumbelos, Southern Colombia

Ornithological surveys in Serranía de los Churumbelos, southern Colombia Paul G. W . Salaman, Thomas M. Donegan and Andrés M. Cuervo Cotinga 12 (1999): 29– 39 En el marco de dos expediciones biológicos y Anglo-Colombian conservation expeditions — ‘Co conservacionistas anglo-colombianas multi-taxa, s lombia ‘98’ and the ‘Colombian EBA Project’. Seven llevaron a cabo relevamientos de aves en lo Serranía study sites were investigated using non-systematic de los Churumbelos, Cauca, en julio-agosto 1988, y observations and standardised mist-netting tech julio 1999. Se estudiaron siete sitios enter en 350 y niques by the three authors, with Dan Davison and 2500 m, con 421 especes registrados. Presentamos Liliana Dávalos in 1998. Each study site was situ un resumen de los especes raros para cada sitio, ated along an altitudinal transect at c. 300- incluyendo los nuevos registros de distribución más m elevational steps, from 350–2500 m on the Ama significativos. Los resultados estabilicen firme lo zonian slope of the Serranía. Our principal aim was prioridad conservacionista de lo Serranía de los to allow comparisons to be made between sites and Churumbelos, y aluco nos encontramos trabajando with other biological groups (mammals, herptiles, junto a los autoridades ambientales locales con insects and plants), and, incorporating geographi cuiras a lo protección del marcizo. cal and anthropological information, to produce a conservation assessment of the region (full results M e th o d s in Salaman et al.4). A sizeable part of eastern During 14 July–17 August 1998 and 3–22 July 1999, Cauca — the Bota Caucana — including the 80-km- ornithological surveys were undertaken in Serranía long Serranía de los Churumbelos had never been de los Churumbelos, Department of Cauca, by two subject to faunal surveys. -

Ultimate Bolivia Tour Report 2019

Titicaca Flightless Grebe. Swimming in what exactly? Not the reed-fringed azure lake, that’s for sure (Eustace Barnes) BOLIVIA 8 – 29 SEPTEMBER / 4 OCTOBER 2019 LEADER: EUSTACE BARNES Bolivia, indeed, THE land of parrots as no other, but Cotingas as well and an astonishing variety of those much-loved subfusc and generally elusive denizens of complex uneven surfaces. Over 700 on this tour now! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Blue-throated Macaws hoping we would clear off and leave them alone (Eustace Barnes) Hopefully, now we hear of colourful endemic macaws, raucous prolific birdlife and innumerable elusive endemic denizens of verdant bromeliad festooned cloud-forests, vast expanses of rainforest, endless marshlands and Chaco woodlands, each ringing to the chorus of a diverse endemic avifauna instead of bleak, freezing landscapes occupied by impoverished unhappy peasants. 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com That is the flowery prose, but Bolivia IS that great destination. The tour is no longer a series of endless dusty journeys punctuated with miserable truck-stop hotels where you are presented with greasy deep-fried chicken and a sticky pile of glutinous rice every day. The roads are generally good, the hotels are either good or at least characterful (in a good way) and the food rather better than you might find in the UK. The latter perhaps not saying very much. Palkachupe Cotinga in the early morning light brooding young near Apolo (Eustace Barnes). That said, Bolivia has work to do too, as its association with that hapless loser, Che Guevara, corruption, dust and drug smuggling still leaves the country struggling to sell itself. -

Bird Abundances in Primary and Secondary Growths in Papua New Guinea: a Preliminary Assessment

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol.3 (4):373-388, 2010 Research Article Bird abundances in primary and secondary growths in Papua New Guinea: a preliminary assessment Kateřina Tvardíková1 1 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Biological Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 31, CZ- 370 05 České Budějovice. Email: <[email protected] Abstract Papua New Guinea is the third largest remaining area of tropical forest after the Amazon and Congo basins. However, the growing intensity of large-scale slash-and-burn agriculture and logging call for conservation research to assess how local people´s traditional land-use practices result in conservation of local biodiversity, of which a species-rich and diverse component is the avian community. With this in mind, I conducted a preliminary survey of birds in small-scale secondary plots and in adjacent primary forest in Wanang Conservation Area in Papua New Guinea. I used mist-netting, point counts, and transect walks to compare the bird communities of 7-year-old secondary growth, and neighboring primary forest. The preliminary survey lasted 10 days and was conducted during the dry season (July) of 2008. I found no significant differences in summed bird abundances between forest types. However, species richness was higher in primary forest (98 species) than in secondary (78 species). The response of individual feeding guilds was also variable. Two habitats differed mainly in presence of canopy frugivores, which were more abundant (more than 80%) in primary than in secondary forests. A large difference (70%) was found also in understory and mid-story insectivores. Species occurring mainly in secondary forest were Hooded Butcherbird (Cracticus cassicus), Brown Oriole (Oriolus szalayi), and Helmeted Friarbird (Philemon buceroides). -

List of the Birds of Peru Lista De Las Aves Del Perú

LIST OF THE BIRDS OF PERU LISTA DE LAS AVES DEL PERÚ By/por MANUEL A. -

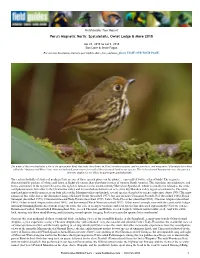

Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2018

Field Guides Tour Report Peru's Magnetic North: Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2018 Jun 23, 2018 to Jul 5, 2018 Dan Lane & Jesse Fagan For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. The name of this tour highlights a few of the spectacular birds that make their homes in Peru's northern regions, and we saw these, and many more! This might have been called the "Antpittas and More" tour, since we had such great views of several of these formerly hard-to-see species. This Ochre-fronted Antpitta was one; she put on a fantastic display for us! Photo by participant Linda Rudolph. The eastern foothills of Andes of northern Peru are one of those special places on the planet… especially if you’re a fan of birds! The region is characterized by pockets of white sand forest at higher elevations than elsewhere in most of western South America. This translates into endemism, and hence our interest in the region! Of course, the region is famous for the award-winning Marvelous Spatuletail, which is actually not related to the white sand phenomenon, but rather to the Utcubamba valley and its rainshadow habitats (an arm of the dry Marañon valley region of endemism). The white sand endemics actually span areas on both sides of the Marañon valley and include several species described to science only since about 1976! The most famous of this collection is the diminutive Long-whiskered Owlet (described 1977), but also includes Cinnamon Screech-Owl (described 1986), Royal Sunangel (described 1979), Cinnamon-breasted Tody-Tyrant (described 1979), Lulu’s Tody-Flycatcher (described 2001), Chestnut Antpitta (described 1987), Ochre-fronted Antpitta (described 1983), and Bar-winged Wood-Wren (described 1977). -

Southern Wing-Banded Antbird, Myrmornis Torquata Myrmornithinae

Thamnophilidae: Antbirds, Species Tree I Northern Wing-banded Antbird, Myrmornis stictoptera ⋆Southern Wing-banded Antbird, Myrmornis torquata ⋆ Myrmornithinae Spot-winged Antshrike, Pygiptila stellaris Russet Antshrike, Thamnistes anabatinus Rufescent Antshrike, Thamnistes rufescens Guianan Rufous-rumped Antwren, Euchrepomis guianensus ⋆Western Rufous-rumped Antwren, Euchrepomis callinota Euchrepomidinae Yellow-rumped Antwren, Euchrepomis sharpei Ash-winged Antwren, Euchrepomis spodioptila Chestnut-shouldered Antwren, Euchrepomis humeralis ⋆Stripe-backed Antbird, Myrmorchilus strigilatus ⋆Dot-winged Antwren, Microrhopias quixensis ⋆Yapacana Antbird, Aprositornis disjuncta ⋆Black-throated Antbird, Myrmophylax atrothorax ⋆Gray-bellied Antbird, Ammonastes pelzelni MICRORHOPIINI ⋆Recurve-billed Bushbird, Neoctantes alixii ⋆Black Bushbird, Neoctantes niger Rondonia Bushbird, Neoctantes atrogularis Checker-throated Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla fulviventris Western Ornate Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla ornata Eastern Ornate Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla hoffmannsi Rufous-tailed Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla erythrura White-eyed Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla leucophthalma Brown-bellied Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla gutturalis Foothill Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla spodionota Madeira Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla amazonica Roosevelt Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla dentei Negro Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla pyrrhonota Brown-backed Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla fjeldsaai ⋆Napo Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla haematonota ⋆Streak-capped Antwren, Terenura -

Peru's Magnetic North: Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2015

Field Guides Tour Report Peru's Magnetic North: Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2015 Jul 22, 2015 to Aug 2, 2015 Dan Lane & Pepe Rojas For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. The Rufous-crested Coquette is always a crowd-pleaser. Photo by participant Tim Skillin. As is becoming increasingly obvious, the El Niño of 2015-6 is shaping up to be a bad one! This has affected weather globally, which certainly has been obvious in Peru. On the Pacific coast, the usually cool, overcast weather has been warmer and sunnier. Meanwhile, on the Amazonian slope of the Andes, the May-to-September dry season has been marked by considerably more precipitation than normal. We witnessed this first hand but, happily, it didn't make birding in San Martin impossible; we just had to have some patience. And the birding in the Peruvian departments of San Martin and Amazonas was incredible! On our first day, driving from Tarapoto to Moyobamba, we enjoyed the Oilbird cave under the highway and some open-country birds that are rather rare and local in Peru (and not much easier to see elsewhere!), such as Cinereous-breasted Spinetail, Masked Duck, and Black-billed Seed-Finch. Our next day, we continued to enjoy the interesting avifauna of the unique Mayo Valley, where there are influences of Amazonian rainforest (Green- backed Trogon, Scaly-breasted Wren, Peruvian Warbling-Antbird, and Fiery-capped Manakin), the drier cerrado of Bolivia and Brazil (Stripe-necked Tody-Tyrant, Little Nightjar, and Pale-breasted Thrush), and one or two elements all its own (the undescribed "Striped" Manakin). -

State of the Amazon: Freshwater Connectivity and Ecosystem Health WWF LIVING AMAZON INITIATIVE SUGGESTED CITATION

REPORT LIVING AMAZON 2015 State of the Amazon: Freshwater Connectivity and Ecosystem Health WWF LIVING AMAZON INITIATIVE SUGGESTED CITATION Macedo, M. and L. Castello. 2015. State of the Amazon: Freshwater Connectivity and Ecosystem Health; edited by D. Oliveira, C. C. Maretti and S. Charity. Brasília, Brazil: WWF Living Amazon Initiative. 136pp. PUBLICATION INFORMATION State of the Amazon Series editors: Cláudio C. Maretti, Denise Oliveira and Sandra Charity. This publication State of the Amazon: Freshwater Connectivity and Ecosystem Health: Publication editors: Denise Oliveira, Cláudio C. Maretti, and Sandra Charity. Publication text editors: Sandra Charity and Denise Oliveira. Core Scientific Report (chapters 1-6): Written by Marcia Macedo and Leandro Castello; scientific assessment commissioned by WWF Living Amazon Initiative (LAI). State of the Amazon: Conclusions and Recommendations (chapter 7): Cláudio C. Maretti, Marcia Macedo, Leandro Castello, Sandra Charity, Denise Oliveira, André S. Dias, Tarsicio Granizo, Karen Lawrence WWF Living Amazon Integrated Approaches for a More Sustainable Development in the Pan-Amazon Freshwater Connectivity Cláudio C. Maretti; Sandra Charity; Denise Oliveira; Tarsicio Granizo; André S. Dias; and Karen Lawrence. Maps: Paul Lefebvre/Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC); Valderli Piontekwoski/Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM, Portuguese acronym); and Landscape Ecology Lab /WWF Brazil. Photos: Adriano Gambarini; André Bärtschi; Brent Stirton/Getty Images; Denise Oliveira; Edison Caetano; and Ecosystem Health Fernando Pelicice; Gleilson Miranda/Funai; Juvenal Pereira; Kevin Schafer/naturepl.com; María del Pilar Ramírez; Mark Sabaj Perez; Michel Roggo; Omar Rocha; Paulo Brando; Roger Leguen; Zig Koch. Front cover Mouth of the Teles Pires and Juruena rivers forming the Tapajós River, on the borders of Mato Grosso, Amazonas and Pará states, Brazil. -

WVCP Bird Paper

Mongabay.com Open Access Journal - Tropical Conservation Science Vol.4 (3):317-348, 2011 Research Article Bird communities of the lower Waria Valley, Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea: a comparison between habitat types 1* 2,3 1,4 Jeff Dawson , Craig Turner , Oscar Pileng , Andrew Farmer1, Cara McGary1, Chris Walsh1, Alexia Tamblyn2 and Cossey Yosi5 1Coral Cay Conservation, 1st Floor Block, 1 Elizabeth House, 39 York Road, London SW1 7NQ UK 2Previous address: Jaquelin Fisher Associates, 4 Yukon Road, London SW12 9PU, UK 3Current address: Zoological Society of London, Regents Park, London NW1 4RY, UK 4FORCERT, Walindi Nature Centre, Talasea Highway, West New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea 5Papua New Guinea Forest Research Institute, PO Box 314, Lae, Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea *Correspondence: Jeff Dawson < [email protected]> Abstract From June, 2007, to February, 2009, the Waria Valley Community Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods Project (WVCP) completed an inventory survey of the birds of the lower Waria Valley, Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea. Four land use types -- agricultural, secondary forest edge, primary forest edge and primary forest -- were surveyed using Mackinnon list surveys. In total, 125 species representing 43 families were identified, of which 54 (43.2%) are endemic to the islands of New Guinea and the Bismark Archipelago. The avifauna of primary forest edge and primary forest was more species rich and diverse than that of agricultural habitats. Agricultural habitats also differed significantly in both overall community composition and some aspects of guild composition compared to all three forested habitats. Nectarivores and insectivore-frugivores formed a significantly larger proportion of species in agricultural habitats, whereas obligate frugivores formed a significantly greater proportion in forested habitats.