Arxiv:Astro-Ph/0605132 V1 4 May 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expected Differences Between AGB Stars in the LMC and the SMC Due to Differences in Chemical Composition

New Views of the Magellanic Clouds fA U Symposium, Vol. 190, 1999 Y.-H. Chu, N.B. Suntzef], J.E. Hesser, and D.A. Bohlender, eds. Expected Differences between AGB Stars in the LMC and the SMC Due to Differences in Chemical Composition Ju. Frantsman Astronomical Institute, Latvian University, Raina Blvd. 19, Riga, LV-1586, LATVIA Abstract. Certain aspects of the AGB population, such as the relative number of M and N stars, the mass loss rates, and the initial masses of carbon- oxygen cores, depend on the initial heavy element abundance Z. I have calculated synthetic populations of AGB stars for different initial Z values taking into consideration the evolution of single and close binary stars. I present the results of population syntheses of AGB stars in clusters as a function of different initial chemical compositions. The relation for the tip luminosity of AGB stars versus cluster age as a function of Z is presented and is used to determine the ages for a number of clusters in the LMC and the SMC, including clusters with no previous age determinations. Population simulations show that for low heavy element abundance (Z = 0.001) few M stars are formed with respect to the number of carbon stars. However, the total number of all AGB stars in clusters is not affected by the initial chemical composition. As a result of the evolution of close binary components after the mass exchange, an increase in the range of limiting values of the thermal pulsing AGB star luminosities is expected. The difference between the maximum luminosity on the AGB of single star and the luminosity of a star after a mass exchange event in a close binary system may be as great as 1 magnitude for very young clusters. -

Atlas Menor Was Objects to Slowly Change Over Time

C h a r t Atlas Charts s O b by j Objects e c t Constellation s Objects by Number 64 Objects by Type 71 Objects by Name 76 Messier Objects 78 Caldwell Objects 81 Orion & Stars by Name 84 Lepus, circa , Brightest Stars 86 1720 , Closest Stars 87 Mythology 88 Bimonthly Sky Charts 92 Meteor Showers 105 Sun, Moon and Planets 106 Observing Considerations 113 Expanded Glossary 115 Th e 88 Constellations, plus 126 Chart Reference BACK PAGE Introduction he night sky was charted by western civilization a few thou - N 1,370 deep sky objects and 360 double stars (two stars—one sands years ago to bring order to the random splatter of stars, often orbits the other) plotted with observing information for T and in the hopes, as a piece of the puzzle, to help “understand” every object. the forces of nature. The stars and their constellations were imbued with N Inclusion of many “famous” celestial objects, even though the beliefs of those times, which have become mythology. they are beyond the reach of a 6 to 8-inch diameter telescope. The oldest known celestial atlas is in the book, Almagest , by N Expanded glossary to define and/or explain terms and Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian with Roman citizenship who lived concepts. in Alexandria from 90 to 160 AD. The Almagest is the earliest surviving astronomical treatise—a 600-page tome. The star charts are in tabular N Black stars on a white background, a preferred format for star form, by constellation, and the locations of the stars are described by charts. -

1. INTRODUCTION Formed Via the Accretion And/Or Merger of Dwarf Satellite Galaxies (Searle & Zinn 1978;Coü Te Et Al

THE ASTRONOMICAL JOURNAL, 122:220È231, 2001 July ( 2001. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. THE LINE-OF-SIGHT DEPTH OF POPULOUS CLUSTERS IN THE SMALL MAGELLANIC CLOUD HUGH H. CROWL1 AND ATA SARAJEDINI2,3 Department of Astronomy, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT 06459-0123; hugh=astro.yale.edu; ata=astro.uÑ.edu ANDRE S E. PIATTI ObservatorioAstroo mico, Universidad Nacional de Cordoba, Laprida 854, Co rdoba, 5000, Argentina;andres=mail.oac.uncor.edu DOUG GEISLER Grupo de Astronomia, Departmento de Fisica, Universidad deConcepcio n, Casilla 160-C, Concepcio n, Chile; doug=kukita.cfm.udec.cl EDUARDO BICA Departamento de Astronomia, Instituto de Fisica, UFRGS, CP 15051, 91501-970, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil; bica=if.ufrgs.br JUAN J. CLARIA ObservatorioAstroo mico, Laprida 854, Co rdoba, 5000, Argentina; claria=mail.oac.uncor.edu AND JOA8 O F. C. SANTOS,JR. Departamento de Fisica, ICEx, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, CP 702, 30123-970 Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil; jsantos=Ðsica.ufmg.br Received 2000 November 14; accepted 2001 March 11 ABSTRACT We present an analysis of age, metal abundance, and positional data on populous clusters in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) with the ultimate aim of determining the line-of-sight (LOS) depth of the SMC by using these clusters as proxies. Our data set contains 12 objects and is limited to clusters with the highest-quality data for which the ages and abundances are best known and can be placed on an inter- nally consistent scale. We have analyzed the variation of the clustersÏ properties with position on the sky and with line-of-sight depth. -

Star Clusters As Witnesses of the Evolutionary History of the Small Magellanic Cloud

JENAM, Symposium 5: Star Clusters – Witnesses of Cosmic History Star Clusters as Witnesses of the Evolutionary History of the Small Magellanic Cloud Eva K. Grebel Astronomisches Rechen-Institut 11.0Z9.2e00n8 trum für AstrGroebnel,o JEmNAMie Sy mdp.e 5:r S MUC nStairv Celusrtesrsität Heidelbe0 rg My collaborators: ! PhD student Katharina Glatt ! PhD student Andrea Kayser (both University of Basel & University of Heidelberg) ! Andreas Koch (U Basel & UCLA / OCIW) ! Jay Gallagher, D. Harbeck (U Wisc) ! Elena Sabbi (U Heidelberg & STScI) ! Antonella Nota, Marco Sirianni (STScI) ! Monica Tosi, Gisella Clementini (U Bologna) ! Andrew Cole (U Tasmania) ! Gary Da Costa (ANU) 11.09.2008 Grebel, JENAM Symp. 5: SMC Star Clusters 1 NGC 416 (OGLE) Tracers of the Age-Metallicity Relation: ! Star clusters: ! Easily identifiable. ! Chronometers of intense star formation events. ! Single-age, single-metallicity fossils of local conditions. ! Star clusters in the SMC: ! Clusters formed (and survived) for most of its lifetime " Closely spaced set of age tracers! " Unique property of the SMC. # Milky Way: No comparable set of intermediate-age, populous clusters. # LMC: Age gap at intermediate ages. 11.09.2008 Grebel, JENAM Symp. 5: SMC Star Clusters 2 Cluster-based Age-Metallicity Relation: Photometry Spectroscopy After Da Costa 2002 An inhomogeneous sample: ! Photometric and spectroscopic metallicities from different techniques ! Photometric ages from ground-/space-based data of differing depth 11.09.2008 Grebel, JENAM Symp. 5: SMC Star Clusters 3 Getting Homogeneous Ages and Metallicities: PhD thesis Katharina Glatt ! HST / ACS program to obtain deep CMDs (PI: Gallagher) $ GO 10396, 29 orbits, executed 2005 – 2006. $ 6 populous intermediate-age clusters, 1 globular cluster: NGC 419, Lindsay 38, NGC 416, 339, Kron 3, Lindsay 1, NGC 121. -

The Star-Forming Region NGC 346 in the Small Magellanic Cloud With

ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION IN APJ—DRAFT VERSION APRIL 22, 2007 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 6/22/04 THE STAR-FORMING REGION NGC 346 IN THE SMALL MAGELLANIC CLOUD WITH HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE ACS OBSERVATIONS. II. PHOTOMETRIC STUDY OF THE INTERMEDIATE-AGE STAR CLUSTER BS 90∗ BOYKE ROCHAU AND DIMITRIOS A. GOULIERMIS Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany WOLFGANG BRANDNER UCLA, Div. of Astronomy, 475 Portola Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1547, USA and Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany ANDREW E. DOLPHIN Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA and Raytheon Corporation, USA AND THOMAS HENNING Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany Accepted for Publication in ApJ — Draft Version April 22, 2007 ABSTRACT We present the results of our investigation of the intermediate-age star cluster BS 90, located in the vicinity of the H II region N 66 in the SMC, observed with HST/ACS. The high-resolution data provide a unique opportu- nity for a very detailed photometricstudy performedon one of the rare intermediate-agerich SMC clusters. The complete set of observations is centered on the association NGC 346 and contains almost 100,000 stars down to V ≃ 28 mag. In this study we focus on the northern part of the region, which covers almost the whole stellar content of BS 90. We construct its stellar surface density profile and derive structural parameters. Isochrone fits on the CMD of the cluster results in an age of about 4.5 Gyr. The luminosity function is constructed and the present-day mass function of BS 90 has been obtained using the mass-luminosity relation, derived from the isochrone models. -

Magellanic Clouds Stellar Clusters. II. New $B,V$ CM Diagrams for 6 LMC

A&A 387, 861–889 (2002) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20020376 & c ESO 2002 Astrophysics Magellanic Clouds stellar clusters. II. New B; V CM diagrams for 6 LMC and 10 SMC clusters? A. Matteucci1,V.Ripepi2, E. Brocato3, and V. Castellani1 1 Dipartimento di Fisica, Universit`a di Pisa, Piazza Torricelli 2, 56100 Pisa, Italy 2 Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Via Moiariello 16, 80131 Napoli, Italy 3 Osservatorio Astronomico di Collurania, Via M. Maggini, 64100 Teramo, Italy Received 10 August 2001 / Accepted 29 January 2002 Abstract. We present new CCD photometry for 6 LMC and 10 SMC stellar clusters taken at the ESO 1.54-m Danish Telescope in La Silla, to extend a previous investigation on Magellanic Clouds clusters based on HST snap- shots. Thanks to the much larger area covered by the Danish detector, we investigate the spatial distribution of cluster stars, giving V ,(B − V ) CM diagrams for both clusters and surrounding fields. Evidence of a complex history of star formation in the Clouds is outlined, showing that old field populations in both Clouds have metal- licities much lower than normally adopted for them (Z =0.008 and Z =0.004 for LMC and SMC respectively), with SMC field stars more metal poor than in the LMC. Observational data concerning the red clump of field stars in both Clouds are briefly discussed. Key words. galaxies: clusters: general – galaxies: stellar content – galaxies: Magellanic Clouds 1. Introduction order to allow the investigation of stellar populations in both Clouds. The Magellanic Clouds (MC) are well-known targets for Section 2 gives information on the observations and on the investigation of simple stellar populations, since they the adopted data reduction procedures. -

The Insidious Boosting of Thermally Pulsing Asymptotic Giant Branch Stars in Intermediate-Age Magellanic Cloud Clusters

The Astrophysical Journal, 777:142 (11pp), 2013 November 10 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/777/2/142 C 2013. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. THE INSIDIOUS BOOSTING OF THERMALLY PULSING ASYMPTOTIC GIANT BRANCH STARS IN INTERMEDIATE-AGE MAGELLANIC CLOUD CLUSTERS Leo´ Girardi1, Paola Marigo2, Alessandro Bressan3, and Philip Rosenfield4 1 Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova-INAF, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, I-35122 Padova, Italy 2 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia Galileo Galilei, Universita` di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 3, I-35122 Padova, Italy 3 SISSA, via Bonomea 365, I-34136 Trieste, Italy 4 Department of Astronomy, University of Washington, Box 351580, Seattle, WA 98195, USA Received 2013 July 1; accepted 2013 August 26; published 2013 October 23 ABSTRACT In the recent controversy about the role of thermally pulsing asymptotic giant branch (TP-AGB) stars in evolutionary population synthesis (EPS) models of galaxies, one particular aspect is puzzling: TP-AGB models aimed at reproducing the lifetimes and integrated fluxes of the TP-AGB phase in Magellanic Cloud (MC) clusters, when incorporated into EPS models, are found to overestimate, to various extents, the TP-AGB contribution in resolved star counts and integrated spectra of galaxies. In this paper, we call attention to a particular evolutionary aspect, linked to the physics of stellar interiors, that in all probability is the main cause of this conundrum. As soon as stellar populations intercept the ages at which red giant branch stars first appear, a sudden and abrupt change in the lifetime of the core He-burning phase causes a temporary “boost” in the production rate of subsequent evolutionary phases, including the TP-AGB. -

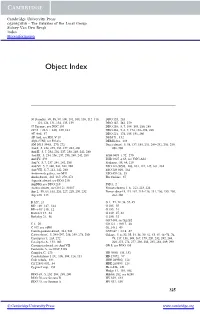

Object Index

Cambridge University Press 0521651816 - The Galaxies of the Local Group Sidney Van Den Bergh Index More information Object Index 30 Doradus, 49, 88, 99, 100, 101, 108, 110, 112–116, DDO 155, 263 121, 124, 131, 134, 135, 139 DDO 187, 263, 279 47 Tucanae, see NGC 104 DDO 210, 5, 7, 194–195, 280, 288 287.5 + 22.5 + 240, 139, 161 DDO 216, 5, 6, 7, 174, 192–194, 280 AE And, 37 DDO 221, 174, 188–191, 280 AF And, see M31 V 19 DEM 71, 132 Alpha UMi, see Polaris DEM L316, 133 AM 1013-394A, 270, 272 Draco dwarf, 5, 58, 137, 185, 231, 249–252, 256, 259, And I, 5, 234, 235, 236, 237, 242, 280 262, 280 And II, 5, 7, 234, 236, 237, 238, 240, 242, 280 And III, 5, 234, 236, 237, 238, 240, 242, 280 EGB 0419 + 72, 270 And IV, 234 EGB 0427 + 63, see UGC-A92 And V, 5, 7, 237–240, 242, 280 Eridanus, 58, 64, 229 And VI, 5, 7, 240, 241, 242, 280 ESO 121-SC03, 103, 104, 124, 125, 161, 162 And VII, 5, 7, 241, 242, 280 ESO 249-010, 264 Andromeda galaxy, see M31 ESO 439-26, 55 Antlia dwarf, 265–267, 270, 272 Eta Carinae, 37 Aquarius dwarf, see DDO 210 AqrDIG, see DDO 210 F8D1, 2 Arches cluster, see G0.121+0.017 Fornax clusters 1–6, 222, 223, 224 Arp 2, 58, 64, 161, 226, 227, 228, 230, 232 Fornax dwarf 5, 94, 167, 219–226, 231, 256, 259, 260, Arp 220, 113 262, 280 B 327, 24 G 1, 27, 32, 34, 35, 45 BD +40◦ 147, 164 G 105, 35 BD +40◦ 148, 12 G 185, 31 Berkeley 17, 54 G 219, 27, 32 Berkeley 21, 56 G 280, 32 G0.7-0.0, see Sgr B2 C1,20 G0.121 + 0.017, 48 C 107, see vdB0 G1.1-0.1, 49 Camelopardalis dwarf, 241, 242 G359.87 + 0.18, 67 Carina dwarf, 5, 245–247, 256, 259, -

Aglomerados Estelares Da Pequena Nuvem De Magalh˜Aes

Universidade de S˜ao Paulo Instituto de Astronomia, Geof´ısica e Ciˆencias Atmosf´ericas Departamento de Astronomia Bruno Dias Aglomerados estelares da Pequena Nuvem de Magalh˜aes S˜ao Paulo 2010 Bruno Dias Aglomerados estelares da Pequena Nuvem de Magalh˜aes Disserta¸c˜ao apresentada ao Departamento de Astronomia do Instituto de Astronomia, Geof´ısica e Ciˆencias Atmosf´ericas da Universidade de S˜ao Paulo como parte dos requisitos para a obten¸c˜ao do t´ıtulo de Mestre em Ciˆencias. Area´ de Concentra¸c˜ao: Astronomia Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Beatriz Barbuy S˜ao Paulo 2010 A` minha fam´ılia. Agradecimentos A` professora Beatriz Barbuy, por acreditar em mim e confiar no meu trabalho, por todas as oportunidades que me proporcionou desde a inicia¸c˜ao cient´ıfica, em 2005; Aos pesquisadores: Alan Alves-Brito, Alexandre Soares, Bas´ılio Santiago, Bernardo Borges, Jo˜ao Francisco Santos, Jo˜ao Steiner, Leandro Kerber, Marcos Diaz, Paula Coelho, Rodolfo Smiljanic, Thais Idiart, pelas contribui¸c˜oes ao longo destes anos; A` professora Silvia Rossi por apontar minhas falhas durante o mestrado e estimular a continuar sempre melhorando; A` FAPESP, pelo investimento, sob o projeto no: 2007/56816-8; As` Institui¸c˜oes: IAG-USP, SOAR, LNA, ESO, ON, SPNSA; A` minha fam´ılia: Alvino, Nilda, Gabriel, Paula, Mauro e M´arcia, pelo apoio e incentivo; Aos colegas: Bod˜ao, Bia, Thais, Phillip, Cristiano, grandes amigos desde a gradua¸c˜ao, e a Felipe’s, Fernanda, Gustavo Rocha, Rodrigo, Tiago Ricci pela descontra¸c˜ao musical; A` Marina, por me aguentar na sala, a Michelino e Jos´eAdriano, por tornarem poss´ıvel meu trabalho; A todos os amigos que rezaram por mim; Esta disserta¸c˜ao foi escrita em LATEX com a classe IAGTESE, para teses e disserta¸c˜oes do IAG. -

A Comparison of Optical and Near-Infrared Colours of Magellanic Cloud Star Clusters with Predictions of Simple Stellar Population Models

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 385, 1535–1560 (2008) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.12935.x A comparison of optical and near-infrared colours of Magellanic Cloud star clusters with predictions of simple stellar population models , P. M. Pessev,1 P. Goudfrooij,1 T. H. Puzia2 and R. Chandar3 4 1Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 2Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, 5071 West Saanich Road, Victoria, BC V9E 2E7, Canada 3The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 813 Santa Barbara Street, Pasadena, CA 91101-1292, USA 4Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Toledo, 2801 West Bancroft Street, Toledo, OH 43606, USA Accepted 2008 January 8. Received 2008 January 6; in original form 2007 July 3 ABSTRACT We present integrated JHKS Two-Micron All-Sky Survey photometry and a compilation of integrated-light optical photoelectric measurements for 84 star clusters in the Magellanic Clouds. These clusters range in age from ≈200 Myr to >10 Gyr, and have [Fe/H] values from −2.2 to −0.1 dex. We find a spread in the intrinsic colours of clusters with similar ages and metallicities, at least some of which is due to stochastic fluctuations in the number of bright stars residing in low-mass clusters. We use 54 clusters with the most-reliable age and metallicity estimates as test particles to evaluate the performance of four widely used simple stellar population models in the optical/near-infrared (near-IR) colour–colour space. All mod- els reproduce the reddening-corrected colours of the old (10 Gyr) globular clusters quite well, but model performance varies at younger ages. -

INFRARED SURFACE BRIGHTNESS FLUCTUATIONS of MAGELLANIC STAR CLUSTERS1 Rosa A

The Astrophysical Journal, 611:270–293, 2004 August 10 A # 2004. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. INFRARED SURFACE BRIGHTNESS FLUCTUATIONS OF MAGELLANIC STAR CLUSTERS1 Rosa A. Gonza´lez Centro de Radioastronomı´a y Astrofı´sica, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Me´xico, Campus Morelia, Michoaca´n CP 58190, Mexico; [email protected] Michael C. Liu Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822; [email protected] and Gustavo Bruzual A. Centro de Investigaciones de Astronomı´a, Apartado Postal 264, Me´rida 5101-A, Venezuela; [email protected] Received 2003 November 27; accepted 2004 April 16 ABSTRACT We present surface brightness fluctuations (SBFs) in the near-IR for 191 Magellanic star clusters available in the Second Incremental and All Sky Data releases of the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS) and compare them with SBFs of Fornax Cluster galaxies and with predictions from stellar population models as well. We also construct color-magnitude diagrams (CMDs) for these clusters using the 2MASS Point Source Catalog (PSC). Our goals are twofold. The first is to provide an empirical calibration of near-IR SBFs, given that existing stellar population synthesis models are particularly discrepant in the near-IR. Second, whereas most previous SBF studies have focused on old, metal-rich populations, this is the first application to a system with such a wide range of ages (106 to more than 1010 yr, i.e., 4 orders of magnitude), at the same time that the clusters have a very narrow range of metallicities (Z 0:0006 0:01, i.e., 1 order of magnitude only). -

The Galaxies of the Local Group Sidney Van Den Bergh Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-03743-3 - The Galaxies of the Local Group Sidney van den Bergh Index More information Object Index 30 Doradus, 49, 88, 99, 100, 101, 108, 110, 112–116, DDO 155, 263 121, 124, 131, 134, 135, 139 DDO 187, 263, 279 47 Tucanae, see NGC 104 DDO 210, 5, 7, 194–195, 280, 288 287.5 + 22.5 + 240, 139, 161 DDO 216, 5, 6, 7, 174, 192–194, 280 AE And, 37 DDO 221, 174, 188–191, 280 AF And, see M31V19 DEM 71, 132 Alpha UMi, see Polaris DEM L316, 133 AM 1013-394A, 270, 272 Draco dwarf, 5, 58, 137, 185, 231, 249–252, 256, 259, And I, 5, 234, 235, 236, 237, 242, 280 262, 280 And II, 5, 7, 234, 236, 237, 238, 240, 242, 280 And III, 5, 234, 236, 237, 238, 240, 242, 280 EGB 0419 + 72, 270 And IV, 234 EGB 0427 + 63, see UGC-A92 And V, 5, 7, 237–240, 242, 280 Eridanus, 58, 64, 229 And VI, 5, 7, 240, 241, 242, 280 ESO 121-SC03, 103, 104, 124, 125, 161, 162 And VII, 5, 7, 241, 242, 280 ESO 249-010, 264 Andromeda galaxy, see M31 ESO 439-26, 55 Antlia dwarf, 265–267, 270, 272 Eta Carinae, 37 Aquarius dwarf, see DDO 210 AqrDIG, see DDO 210 F8D1, 2 Arches cluster, see G0.121+0.017 Fornax clusters 1–6, 222, 223, 224 Arp 2, 58, 64, 161, 226, 227, 228, 230, 232 Fornax dwarf 5, 94, 167, 219–226, 231, 256, 259, 260, Arp 220, 113 262, 280 B 327, 24 G 1, 27, 32, 34, 35, 45 BD +40◦ 147, 164 G 105, 35 BD +40◦ 148, 12 G 185, 31 Berkeley 17, 54 G 219, 27, 32 Berkeley 21, 56 G 280, 32 G0.7-0.0, see Sgr B2 C1,20 G0.121 + 0.017, 48 C 107, see vdB0 G1.1-0.1, 49 Camelopardalis dwarf, 241, 242 G359.87 + 0.18, 67 Carina dwarf, 5, 245–247, 256,