Missoula Historic Underground Project: Urban Archaeology, Landscape, and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Cemetery Strategic Plan

M E M O R A N D U M TO: MRA Board of Commissioners FROM: Chris Behan, Assistant Director DATE: November 16, 2020 RE: Missoula Cemetery Strategic Plan (North Reserve-Scott Street URD) At its October 17, 2019 meeting, the MRA Board approved financing one-half of the cost up to $12,750 for a consultant to draft a Strategic Plan for the Missoula Cemetery, which is within the North Reserve – Scott Street Urban Renewal District (NRSS). The Strategic Plan was substantially complete last spring but Covid-19 and some recommendations the Cemetery Board needed to consider, extended the schedule for the City Council consideration of the Strategic Plan until now. L.F. Sloane Consulting, a cemetery planning, management and operations firm with a 38-year history of planning and implementation projects across the country, authored the Strategic Plan. The City Cemetery is currently a component unit of the City’s Public Works Department. The 2014 NRSS Master Plan recommends that the Cemetery create short and long range strategic plan “to assure its relevance and viability in perpetuity, and to arrive at an understanding of future land needs”. The Master Plan made some broad recommendations regarding the Cemetery property but at the Cemetery Board’s request, avoided specific recommendations without more in-depth study. Sloane’s analysis of the Cemetery found that, at the current rate of burials, there are about 7,000 plotted gravesites remaining in the area the Cemetery area uses. That represents about 200 years at the current burial rate. Sloane recognized that the cremation rate is higher in Missoula (and Montana) than much of the rest of the country with many cremains scattered, kept, or buried elsewhere and had recommendations where and when to expand cremain walls and crèches. -

Frommer's Seattle 2004

01 541277 FM.qxd 11/17/03 9:37 AM Page i Seattle 2004 by Karl Samson Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers 01 541277 FM.qxd 11/17/03 9:37 AM Page ii About the Author Karl Samson makes his home in the Northwest. He also covers the rest of Wash- ington for Frommer’s. In addition, Karl is the author of Frommer’s Arizona. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5744 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for per- mission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. -

Rock Rabbits Nature at the Movies

NatMuONTANAralisWinter 2011-2012t Rock Rabbits Nature at the Movies Beautiful Remains Tips for Winter Outings and More page 9 Connecting People with Nature WINTER 2011-12 MONTANA NATURALIST TO PROMOTE AND CULTIVATE THE APPRECIATION, UNDERSTANDING AND STEWARDSHIP OF NATURE THROUGH EDUCATION inside Winter 2011-2012 NatMuONTANAralist Features 4 The Beauty of Winter Plants by Sara Call Looking closer at what remains 6 American Pikas by Allison DeJong Make hay to last the winter long 8 Out of Winter 4 Middle-schoolers learn from annual trek to the Tetons Departments 3 Tidings 9 Get Outside Guide Outdoor safety tips for winter; Special look out for the flea circus!; Pull-Out 6 8 Ansel Adams and more Section 13 Community Focus Get your nature fix at the movies 14 Imprints Meet our new neighbors; miniNaturalists at MNHC; 2011 auction highlights 17 Far Afield Snow Dunes 9 14 You’ve seen them, but do you know what they’re called? 18 Magpie Market 19 Reflections Apple Elves 13 Cover – A Stellar’s jay perches on a snowy Ponderosa pine branch in the Mission Mountains east of Ronan. Reflections – Apples cling to the tree at the tail end of a November snowstorm, up Smith Creek. Cover and Reflections photos by Merle Ann Loman, an outdoor enthusiast living in the Bitterroot Valley located south of Missoula in western Montana. Her adventures start there but will also travel the world. She runs, hikes, bikes, fishes, hunts, skis and always takes photos. www.amontanaview.com No material appearing in Montana Naturalist may be reproduced in part or in whole without the written consent of the publisher. -

Self-Guided Walking Tours

SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOURS No visit to Missoula is complete without taking the time to appreciate the unique attributes of 7. “CATTIN’ AROUND” The Cattin’ Around sculpture adorns Central Park parking garage in the 100 block Downtown. Follow these self-guided walking tours of of West Main Street. Mike Hollern created this whimsical, ferrous cement depiction historical landmarks and public artworks and get to of a sprawled alley cat in 1991 as a project of the City of Missoula Public Arts know the real Missoula, historic and modern. Committee. A small puddle of water collects on the cat’s back to create a birdbath. Compiled by the Missoula Cultural Council and 8. “STUDEBAKER” The Studebaker on the side of the Studebaker Building at 216 West Main Street was Missoula Historic Preservation Commission, these created by noted local artist Stan Hughes in 2000. The work pays tribute to the his- tours are a great way to understand the pulse of the torical background of the Studebaker Building and the heart of the Gasoline Alley historic area, which evolved on West Main Street in the early 1900s and was a proj- city. ect of the City of Missoula Public Arts Committee. 9. “UNTITLED” DOWNTOWN PUBLIC ART The untitled mural on the East Side of the Salvation Army Thrift Store at 339 West Broadway was painted with recycled paint by Joseph Fidance free of charge in 1994. A vital component of any urban landscape, the pres- 10. “E.S. PAXSON MURALS” ence of public art in a community signifies the char- The E.S. -

AN ADVISORY SERVICES PANEL REPORT Midtown Missoula Missoula, Montana

AN ADVISORY SERVICES PANEL REPORT Midtown Missoula Missoula, Montana Urban Land $ Institute Midtown Missoula Missoula, Montana A Redevelopment Plan October 12–17, 2003 An Advisory Services Panel Report ULI–the Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, N.W. Suite 500 West Washington, D.C. 20007-5201 About ULI–the Urban Land Institute LI–the Urban Land Institute is a non- resented include developers, builders, property profit research and education organiza- owners, investors, architects, public officials, plan- tion that promotes responsible leadership ners, real estate brokers, appraisers, attorneys, U in the use of land in order to enhance engineers, financiers, academics, students, and the total environment. librarians. ULI relies heavily on the experience of its members. It is through member involvement The Institute maintains a membership represent- and information resources that ULI has been able ing a broad spectrum of interests and sponsors a to set standards of excellence in development wide variety of educational programs and forums practice. The Institute has long been recognized to encourage an open exchange of ideas and shar- as one of America’s most respected and widely ing of experience. ULI initiates research that quoted sources of objective information on urban anticipates emerging land use trends and issues planning, growth, and development. and proposes creative solutions based on that research; provides advisory services; and pub- This Advisory Services panel report is intended lishes a wide variety of materials to disseminate to further the objectives of the Institute and to information on land use and development. make authoritative information generally avail- able to those seeking knowledge in the field of Established in 1936, the Institute today has more urban land use. -

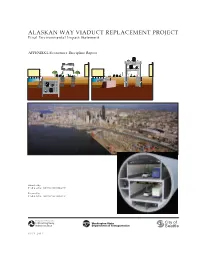

ALASKAN WAY VIADUCT REPLACEMENT PROJECT Final Environmental Impact Statement

ALASKAN WAY VIADUCT REPLACEMENT PROJECT Final Environmental Impact Statement APPENDIX L Economics Discipline Report Submitted by: PARSONS BRINCKERHOFF Prepared by: PARSONS BRINCKERHOFF J U L Y 2 0 1 1 Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement Project Final EIS Economics Discipline Report The Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement Project is a joint effort between the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), and the City of Seattle. To conduct this project, WSDOT contracted with: Parsons Brinckerhoff 999 Third Avenue, Suite 3200 Seattle, WA 98104 In association with: Coughlin Porter Lundeen, Inc. EnviroIssues, Inc. GHD, Inc. HDR Engineering, Inc. Jacobs Engineering Group Inc. Magnusson Klemencic Associates, Inc. Mimi Sheridan, AICP Parametrix, Inc. Power Engineers, Inc. Shannon & Wilson, Inc. William P. Ott Construction Consultants SR 99: Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement Project July 2011 Economics Discipline Report Final EIS This Page Intentionally Left Blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction and Summary ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Build Alternatives Overview ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Overview of Bored Tunnel Alternative (Preferred) .......................................................................... -

Birding in the Missoula and Bitterroot Valleys

Birding in the Missoula and Bitterroot Valleys Five Valleys and Bitterroot Audubon Society Chapters are grassroots volunteer organizations of Montana Audubon and the National Audubon Society. We promote understanding, respect, and enjoyment of birds and the natural world through education, habitat protection, and environmental advocacy. Five Valleys Bitterroot Audubon Society Audubon Society P.O. Box 8425 P.O. Box 326 Missoula, MT 59807 Hamilton, MT 59840 www.fvaudubon.org/ www.bitterrootaudubonorg/ Montana Audubon P.O. Box 595 Helena, MT 59624 406-443-3949 www.mtaudubon.org Status W Sp Su F Bird Species of West-central Montana (most vagrants excluded) _ Harlequin Duck B r r r Relative abundance in suitable habitat by season are: _ Long-tailed Duck t r r c - common to abundant, usually found on every visit in _ Surf Scoter t r r r moderate to large numbers _ White-winged Scoter t r r r u - uncommon, usually present in low numbers but may be _ Common Goldeneye B c c c c _ missed Barrow’s Goldeneye B u c c c _ o - occasional, seen only a few times during the season, not Bufflehead B o c u c _ Hooded Merganser B o c c c present in all suitable habitat _ Common Merganser B c c c c r - rare, one to low numbers occur but not every year _ Red-breasted Merganser t o o _ Status: Ruddy Duck B c c c _ Osprey B c c c B - Direct evidence of breeding _ Bald Eagle B c c c c b - Indirect evidence of breeding _ Northern Harrier B u c c c t - No evidence of breeding _ Sharp-shinned Hawk B u u u u _ Cooper’s Hawk B u u u u Season of occurrence: _ Northern Goshawk B u u u u W - Winter, mid-November to mid-February _ Swainson’s Hawk B u u u Sp - Spring, mid-February to mid-May _ Red-tailed Hawk B c c c c Su - Summer, mid-May to mid-August _ Ferruginous Hawk t r r r F - Fall, mid-August to mid-November _ Rough-legged Hawk t c c c _ Golden Eagle B u u u u This list follows the seventh edition of the AOU check-list. -

Lewis & Clark Trail Adventures Recommended Activities Missoula to Great Falls Questions? Call Us 406-728-7609 Or Email

Lewis & Clark Trail Adventures Recommended Activities Missoula to Great Falls Missoula & surrounding areas Snowbowl Ski Area –summer includes: Zip lines, Chair Rides, Hiking and famous wood fired pizza, Fri-Sun Missoula Day Hikes right from downtown Hiking to the “M”/Mt. Sentinel, “L”/Mt Jumbo walking distance from any downtown location The Trailhead is a great resource for self-guided opportunities and gear you might need Clark Fork River Market – Peoples Market – Farmers Market – Downtown every Saturday morning May-October Inner Tubing – yep, that’s right, a local favorite – float from Sha-Ron River access in E. Missoula to Downtown. Takes about 2 hours, low-water activity only, mid-July – August. Brennans Wave – Surf Wave located at Caras Park in Downtown Missoula Missoula USFS Smoke Jumpers Center – near Missoula airport, largest Smoke Jumper Training base in US Historic Fort Missoula – West end of town near the new Fort Missoula Regional Park & Sports Complex Missoula Art Museum – located downtown at 335 North Pattee Music Scene – Missoula has a lively and growing music scene with newly built state of the art venues The Wilma – located downtown next to Caras Park and VRBO rentals on upper floors Top Hat – one block from the Wilma, also has great food Logjam Presents – coming soon, outdoor venue on the banks of the Blackfoot River Big Sky Brewery Summer Concert Series – outdoor venue and all craft beer proceeds go to local non-profits Kid-Toddler friendly activities Caras Park – The Carousel & Dragons Hollow Splash Montana outdoor -

An Urban Mixed-Use Development in Downtown Missoula, Montana Executive Summary

An Urban Mixed-Use Development in Downtown Missoula, Montana Executive Summary Riverfront Triangle Partners, LLC (RTP), is offering for sale approximately five-acres of property for a mixed-use urban infill project (the Triangle) in the heart of downtown Missoula. The project is located in the Riverfront Triangle Urban Renewal District bordered by the Clark Fork River, Orange Street, and Broadway Street. Providence St. Patrick Hospital is immediately north of the Triangle across Broadway Street. The project is also located in the Central Business District, and will serve as the Western gate- way to downtown Missoula. The Triangle will be supported with over 1,000 parking spaces with a large portion being paid for in collaboration with the City of Missoula using tax increment financing (TIF) and parking revenue bonds. The city intends to use TIF to construct a pedestrian bridge to connect the Tri- angle to McCormick Park on the south bank of the Clark Fork River. On May 8, 2017 the Missoula City Council voted unanimously to conditionally approve the Fox Triangle Land Use and Development Require- ments Agreement. As part of the agreement, the City Council approved vacating a portion of Front Street and Owen Street and RTP’s request to vacate an alley. Approval was also granted to rezone the Riverfront Triangle Special Zoning District to OP1 Open Space and CBD-4 Central Business District. Development must include Residential, Office, Retail, and Restaurant along with the hotel / conference center. The two tracts of property is being offered as a whole or can be purchased separately. View of McCormick Park across from Riverfront Triangle and Hotel Fox Aerial Map of Downtown Missoula Interstate 90 Clark Fork River St. -

Alien Place| the Fort Missoula, Montana, Detention Camp, 1941-1944

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1988 Alien place| The Fort Missoula, Montana, detention camp, 1941-1944 Carol Bulger Van Valkenburg The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Van Valkenburg, Carol Bulger, "Alien place| The Fort Missoula, Montana, detention camp, 1941-1944" (1988). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1500. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1500 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS, ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR, MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE : 19 8 8 AN ALIEN PLACE: THE PORT MISSOULA, MONTANA, DETENTION CAMP 1941-1944 By Carol Bulger Van Valkenburg B.A., University of Montana, 1972 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Interdisciplinary Studies University of Montana 1988 Approved by: Chairman, Boalrdi of Examiners UMI Number: EP34258 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Interpretive Plan

MISSOULA DOWNTOWN HERITAGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN DRAFT - NOVEMBER 2019 Prepared for the Missoula In collaboration with the City of Missoula Historic Preservation Downtown Foundation by Office and Downtown Missoula Partnership. Supported by a Historical Research Associates, Inc. grant from the Montana Department of Commerce Missoula public art. Credit: HRA TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 5 PART 1: FOUNDATION . 13 Purpose and Guiding Principles . 14 Interpretive Goals . 15 Themes . 15 Interpretive Theme Matrices . 19 Setting and Audiences . 23 Issues and Influences Affecting Interpretation . 24 PART 2: EXISTING CONDITIONS . 26 Interpretation in Downtown Missoula . 27 Information and Orientation . 28 Audience Experience . 29 Programming . 31 Potential Partners . 32 PART 3: RECOMMENDATIONS . 37 Introduction . 38 Actions Related to the Connectivity of Downtown Interpretation . 38 Actions Related to Special Events . 41 Actions Related to the Missoula Downtown Master Plan . 41 Actions Related to Pre-Visit/Distance Interpretation . 42 Actions Related to Interpreting Many Perspectives and Underrepresented Heritage . 44 Actions Related to Audience Experience . 47 Actions Related to Program Administration . 51 Actions Related to Scholarship . 51 Actions Related to Additional Interpretative Elements . 52 Actions Related to Collaboration . 52 Actions Related to Educators and Youth Outreach . 54 Actions Related to General Outreach and Marketing . 54 Recommended Implementation Plan . 55 Summary . 69 PART 4: PLANNING RESOURCES . 70 HRA Interpretive Planning Team . 71 Interpretive Planning Advisory Group . 71 Acknowledgements . 71 Glossary . 71 Select Interpretation Resources . 72 Select Topical Resources . 72 INTRODUCTION Downtown heritage mural interpreting local railroad history. Credit: HRA Missoula Downtown Heritage | Interpretive Plan | DRAFT Nov 2019 5 Missoula Textile is a Downtown Missoula heritage business, having been in operation for more than 100 years. -

Twodee's Shadowrun Storytime, Including but Not Limited to the Full Chapter 15 and Chapters 21 and 21.5

1 TwoDee’s Shadowrun Storytime Written by TwoDee Edited and Compiled by Jarboot!!j4xjG8Gxyo4 Further Edited and Compiled by Impatient Asshole Anon What follows is arguably the best series of storytime threads ever created. If you're any sort of fan of Shadowrun—whether you're a new GM, newbie player, or even a veteran—this prose will really help flesh out what sort of fun you can have with the system and setting. It's nearly 400 pages and about 130,000 words, so download this to read on your phone/laptop/ebook/commlink, because this will take a while. I'm Jarboot, a fellow fa/tg/uy and Shadowrun fan. Someone suggested that someone make a compilation of this story for easier reading, so I figured I could do it. Editing is minimal, but I fixed a lot of spelling and general syntax error, most of which were mentioned by TwoDee in a post following the original. There are some little Jackpoint-esque comments from other people from the threads included in the document, which are differentiated by a green color and indented text. I may have included a picture or two in there, too. Also, 2D likes to do some foreshadowing at some points, so keep track of the greentexted dates if you feel confused. All these threads (except number 3, which you can search for using some of the other tags) can be found by searching for the “shadowrun storytime” tag on the /tg/ archive. Jarboot is an extremely helpful fa/tg/uy, but this particular Anon is an impatient asshole who wanted a fully updated version of TwoDee's Shadowrun Storytime, including but not limited to the full Chapter 15 and Chapters 21 and 21.5.