Tasmania: Van Diemen's Land, 1804-1853

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convict Labour and Colonial Society in the Campbell Town Police District: 1820-1839

Convict Labour and Colonial Society in the Campbell Town Police District: 1820-1839. Margaret C. Dillon B.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) University of Tasmania April 2008 I confirm that this thesis is entirely my own work and contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. Margaret C. Dillon. -ii- This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Margaret C. Dillon -iii- Abstract This thesis examines the lives of the convict workers who constituted the primary work force in the Campbell Town district in Van Diemen’s Land during the assignment period but focuses particularly on the 1830s. Over 1000 assigned men and women, ganged government convicts, convict police and ticket holders became the district’s unfree working class. Although studies have been completed on each of the groups separately, especially female convicts and ganged convicts, no holistic studies have investigated how convicts were integrated into a district as its multi-layered working class and the ways this affected their working and leisure lives and their interactions with their employers. Research has paid particular attention to the Lower Court records for 1835 to extract both quantitative data about the management of different groups of convicts, and also to provide more specific narratives about aspects of their work and leisure. -

Cascades Female Factory South Hobart Conservation Management Plan

Cascades Female Factory South Hobart Conservation Management Plan Cascades Female Factory South Hobart Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Tasmanian Department of Environment, Parks, Heritage and the Arts April 2008 Table of contents Table of contents i List of figures iii List of Tables v Project Team vi Acknowledgements vii Executive Summary ix 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to project 2 1.2 History & Limitations on Approach 2 1.3 Description 3 1.4 Key Reports & References 4 1.5 Heritage listings & controls 12 1.6 Site Management 13 1.7 Managing Heritage Significance 14 1.8 Future Management 15 2.0 Female Factory History 27 2.1 Introduction 27 2.2 South Hobart 28 2.3 Women & Convict Transportation: An Overview 29 2.4 Convict Women, Colonial Development & the Labour Market 30 2.5 The Development of the Cascades Female Factory 35 2.6 Transfer to the Sheriff’s Department (1856) 46 2.7 Burial & Disinterment of Truganini 51 2.8 Demolition and subsequent history 51 2.9 Conclusion 52 3.0 Physical survey, description and analysis 55 3.1 Introduction 55 3.2 Setting & context 56 3.3 Extant Female Factory Yards & Structures 57 3.4 Associated Elements 65 3.5 Archaeological Resource 67 3.6 Analysis of Potential Archaeological Resource 88 3.7 Artefacts & Movable Cultural Heritage 96 4.0 Assessment of significance 98 4.1 Introduction 98 4.2 Brief comparative analysis 98 4.3 Assessment of significance 103 5.0 Conservation Policy 111 5.1 Introduction 111 5.2 Policy objectives 111 LOVELL CHEN i 5.3 Significant site elements 112 5.4 Conservation -

Food and Agriculture in the New Colony of Van Diemen's Land, 1803 to 1810

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 122(2), 19R8 19 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE IN THE NEW COLONY OF VAN DIEMEN'S LAND, 1803 TO 1810 by Trevor D. Semmens (with four tables and one text-figures) SEMMENS, T.D., 1988 (31:x): Food and agriculture in the new colony of Van Diemen's Land, 1803 to 1810. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm., 122(2): 19-29. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.122.2.19 ISSN 0080-4703. Entomology Section, Department of Agriculture, G.P.O. Box 192B, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001. The new settlement of Van Diemen's Land and its first eight years are looked at in the light of the feeding of this young colony, and the development of agnculture to allow for sufficiency in food. For many reasons development was slow and progress limited. Key Words: food, agriculture, Van Diemen's Land, famine. " .... For Wise and Good reasons to promote the account; and as they are free settlers you will, as they are the first, allot 200 acres (81 ha) to each Interest of the British Nation and Secure the Advantaies that may be derived from the family and victual them for eighteen months. They are to be allowed the labour of two convicts Fisheries, etc., etc., in the Colony ... to form a Settlement On the South Part of this Coast, or each during that time, and to be supplied with Isles Adjacent, to Counteract any Projects or such portions of seed, grain, garden seeds and stock as can be spared; and also tools." plans the French Republic may arrainie .. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

65 THE ENGLISH AT THE DERWENT, AND THE RISDON SETTLEMENT. BY JAMES BACKHOUSE WALKER. Read October 14th, 1889. ], The English at the Derwent. In a paper which I had the honour to read before the Royal Society last November, entitled " The French in Van Diemen's Land," I endeavoured to show how the discoveries of the French at the Derwent, and their supposed design of occupation, influenced Governor King's mind, and led him to despatch the first English colony to these shores. That paper brought the story to the 12th September, 1803, when the Albion whaler, with Governor Bowen on board, cast anchor in Risdon Cove, five days after the Lady Nelson, which had brought the rest of his small establishment. The choice of such an unsuitable place as Risdon for the site of the first settlement has always been something of a puzzle; and, in order to understand the circumstances which led to this ill-advised selection, it will be necessary to go back some years, and follow the historj'^ of English discovery and exploration in the South of Tasmania. I have already noticed the elaborate and complete surveys of the Canal D'Entrecasteaux, and the Riviere du Nord, made by the French navigators in 1792, and again in 1802 ; but it must be remembered that the results of these expeditions were long kept a profound secret, not only from the English, but from the world in general. Contemporaneously with the French, English navigators had been making independent discoveries and surveys in Southern Tasmania ; and it was solely the knowledge thus acquired that guided Governor King when he instructed Bowen " to fix on a proper place about Risdon's Cove " for the new settlement. -

Briony Neilson, the Paradox of Penal Colonization: Debates on Convict Transportation at the International Prison Congresses

198 French History and Civilization The Paradox of Penal Colonization: Debates on Convict Transportation at the International Prison Congresses 1872-1895 Briony Neilson France’s decision to introduce penal transportation at precisely the moment that Britain was winding it back is a striking and curious fact of history. While the Australian experiment was not considered a model for direct imitation, it did nonetheless provide a foundational reference point for France and indeed other European powers well after its demise, serving as a yardstick (whether positive or negative) for subsequent discussions about the utility of transportation as a method of controlling crime. The ultimate fate of the Australian experiment raised questions in later decades about the utility, sustainability and primary purpose of penal transportation. As this paper will examine, even if penologists saw penal transportation as serving some useful role in tackling crime, the experience of the British in Australia seemed to indicate the strictly limited practicability of the method in terms of controlling crime. Far from a self-sustaining system, penal colonization was premised on an inherent and insurmountable contradiction; namely, that the realization of the colonizing side of the project depended on the eradication of its penal aspect. As the Australian model demonstrated, it was a fundamental truth that the two sides of the system of penal colonization could not be maintained over the long term. The success of the one necessarily implied the withering away of the other. From the point of view of historical analysis, the legacy of the Australian model of penal transportation provides a useful hook for us to identify international ways of thinking Briony Neilson received a PhD in History from the University of Sydney in 2012 and is currently research officer (Monash University) and sessional tutor (University of Sydney). -

The Future of World Heritage in Australia

Keeping the Outstanding Exceptional: The Future of World Heritage in Australia Editors: Penelope Figgis, Andrea Leverington, Richard Mackay, Andrew Maclean, Peter Valentine Editors: Penelope Figgis, Andrea Leverington, Richard Mackay, Andrew Maclean, Peter Valentine Published by: Australian Committee for IUCN Inc. Copyright: © 2013 Copyright in compilation and published edition: Australian Committee for IUCN Inc. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Figgis, P., Leverington, A., Mackay, R., Maclean, A., Valentine, P. (eds). (2012). Keeping the Outstanding Exceptional: The Future of World Heritage in Australia. Australian Committee for IUCN, Sydney. ISBN: 978-0-9871654-2-8 Design/Layout: Pixeldust Design 21 Lilac Tree Court Beechmont, Queensland Australia 4211 Tel: +61 437 360 812 [email protected] Printed by: Finsbury Green Pty Ltd 1A South Road Thebarton, South Australia Australia 5031 Available from: Australian Committee for IUCN P.O Box 528 Sydney 2001 Tel: +61 416 364 722 [email protected] http://www.aciucn.org.au http://www.wettropics.qld.gov.au Cover photo: Two great iconic Australian World Heritage Areas - The Wet Tropics and Great Barrier Reef meet in the Daintree region of North Queensland © Photo: K. Trapnell Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the chapter authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the editors, the Australian Committee for IUCN, the Wet Tropics Management Authority or the Australian Conservation Foundation or those of financial supporter the Commonwealth Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. -

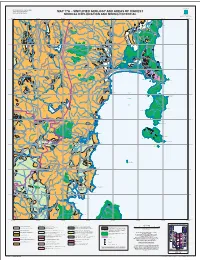

Map 17A − Simplified Geology

MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA MUNICIPAL PLANNING INFORMATION SERIES TASMANIAN GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MAP 17A − SIMPLIFIED GEOLOGY AND AREAS OF HIGHEST MINERAL RESOURCES TASMANIA Tasmania MINERAL EXPLORATION AND MINING POTENTIAL ENERGY and RESOURCES DEPARTMENT of INFRASTRUCTURE SNOW River HILL Cape Lodi BADA JOS psley A MEETUS FALLS Swan Llandaff FOREST RESERVE FREYCINET Courland NATIONAL PARK Bay MOULTING LAGOON LAKE GAME RESERVE TIER Butlers Pt APSLEY LEA MARSHES KE RAMSAR SITE ROAD HWAY HIG LAKE LEAKE Cranbrook WYE LEA KE RIVER LAKE STATE RESERVE TASMAN MOULTING LAGOON MOULTING LAGOON FRIENDLY RAMSAR SITE BEACHES PRIVATE BI SANCTUARY G ROAD LOST FALLS WILDBIRD FOREST RESERVE PRIVATE SANCTUARY BLUE Friendly Pt WINGYS PARRAMORES Macquarie T IER FREYCINET NATIONAL PARK TIER DEAD DOG HILL NATURE RESERVE TIER DRY CREEK EAST R iver NATURE RESERVE Swansea Hepburn Pt Coles Bay CAPE TOURVILLE DRY CREEK WEST NATURE RESERVE Coles Bay THE QUOIN S S RD HAZA THE PRINGBAY THOUIN S Webber Pt RNMIDLAND GREAT Wineglass BAY Macq Bay u arie NORTHE Refuge Is. GLAMORGAN/ CAPE FORESTIER River To o m OYSTER PROMISE s BAY FREYCINET River PENINSULA Shelly Pt MT TOOMS BAY MT GRAHAM DI MT FREYCINET AMOND Gates Bluff S Y NORTH TOOM ERN MIDLA NDS LAKE Weatherhead Pt SOUTHERN MIDLANDS HIGHWA TI ER Mayfield TIER Bay Buxton Pt BROOKERANA FOREST RESERVE Slaughterhouse Bay CAPE DEGERANDO ROCKA RIVULET Boags Pt NATURE RESERVE SCHOUTEN PASSAGE MAN TAS BUTLERS RIDGE NATURE RESERVE Little Seaford Pt SCHOUTEN R ISLAND Swanp TIE FREYCINET ort Little Swanport NATIONAL PARK CAPE BAUDIN -

Conditional Liberation (Parole) in France Christopher L

Louisiana Law Review Volume 39 | Number 1 Fall 1978 Conditional Liberation (Parole) in France Christopher L. Blakesley Repository Citation Christopher L. Blakesley, Conditional Liberation (Parole) in France, 39 La. L. Rev. (1978) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol39/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONDITIONAL LIBERATION (PAROLE) IN FRANCE ChristopherL. Blakesley* I. CONCEPTUAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Anglo-American parole owes its theoretical development and its early systematization, indeed its very existence, to France.' It has been said that France has the genius of inven- * Assistant Professor of Law, Louisiana State University. The author spent the academic year, 1976-1977, in residence at the Faculty of Law, University of Paris (I & II), Paris, France, as Jervey Fellow in Foreign and Comparative Law, Columbia University School of Law. The author owes a debt of gratitude to Georges Levasseur, President of the Labor- atoire de Sociologie Criminelle and Professor of Law, University of Paris II, Professor Roger Pinto, and Professor Jacques LeautA for their kind assistance and hospitality during his stay in Paris. 1. This article is an analysis of the French parole system. It is a precursor of a more extensive work that will be completed in the near future by the writer and Professor Robert A. Fairbanks, University of Arkansas School of Law. -

Transportation from Britain and Ireland, 1615–1875." a Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies

Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish. "Transportation from Britain and Ireland, 1615–1875." A Global History of Convicts and Penal Colonies. Ed. Clare Anderson. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018. 183–210. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350000704.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 20:57 UTC. Copyright © Clare Anderson and Contributors 2018. You may share this work for non- commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 7 Transportation from Britain and Ireland, 1615–1875 Hamish Maxwell-Stewart Despite recent research which has revealed the extent to which penal transportation was employed as a labour mobilization device across the Western empires, the British remain the colonial power most associated with the practice.1 The role that convict transportation played in the British colonization of Australia is particularly well known. It should come as little surprise that the UNESCO World Heritage listing of places associated with the history of penal transportation is entirely restricted to Australian sites.2 The manner in which convict labour was utilized in the development of English (later British) overseas colonial concerns for the 170 years that proceeded the departure of the First Fleet for New South Wales in 1787 is comparatively neglected. There have been even fewer attempts to explain the rise and fall of transportation as a British institution from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. In part this is because the literature on British systems of punishment is dominated by the history of prisons and penitentiaries.3 As Braithwaite put it, the rise of prison has been ‘read as the enduring central question’, sideling examination of alternative measures for dealing with offenders. -

250 State Secretary: [email protected] Journal Editors: [email protected] Home Page

Tasmanian Family History Society Inc. PO Box 191 Launceston Tasmania 7250 State Secretary: [email protected] Journal Editors: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.tasfhs.org Patron: Dr Alison Alexander Fellows: Dr Neil Chick, David Harris and Denise McNeice Executive: President Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Vice President Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 Vice President Peter Cocker (03) 6435 4103 State Secretary Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 State Treasurer Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Committee: Judy Cocker Margaret Strempel Jim Rouse Kerrie Blyth Robert Tanner Leo Prior John Gillham Libby Gillham Sandra Duck By-laws Officer Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Assistant By-laws Officer Maurice Appleyard (03) 6248 4229 Webmaster Robert Tanner (03) 6231 0794 Journal Editors Anita Swan (03) 6326 5778 Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 LWFHA Coordinator Anita Swan (03) 6394 8456 Members’ Interests Compiler Jim Rouse (03) 6239 6529 Membership Registrar Muriel Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Publications Coordinator Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 Public Officer Denise McNeice (03) 6228 3564 State Sales Officer Betty Bissett (03) 6344 4034 Branches of the Society Burnie: PO Box 748 Burnie Tasmania 7320 [email protected] Devonport: PO Box 587 Devonport Tasmania 7310 [email protected] Hobart: PO Box 326 Rosny Park Tasmania 7018 [email protected] Huon: PO Box 117 Huonville Tasmania 7109 [email protected] Launceston: PO Box 1290 Launceston Tasmania 7250 [email protected] Volume 29 Number 2 September 2008 ISSN 0159 0677 Contents Editorial ................................................................................................................ -

Student Activity Sheet H20.3: Convict Clothing

EPISODE 20 | 1818: CHARLES Unit focus: History Year level: Years 3–6 EPISODE CLIP: FENCING ACTIVITY 1: ESCAPE! Subthemes: Culture; Gender roles and stereotypes; Historical events The remoteness of Australia and its formidable landscape and harsh climate made this alien land an ideal choice as a penal settlement in the early 19th century. While the prospect of escape may initially have seemed inconceivable, the desire for freedom proved too strong for the many convicts who attempted to flee into the bush. Early escapees were misguided by the belief that China was only a couple of hundred kilometres to the north. Later, other convicts tried to escape by sea, heading across the Pacific Ocean. In this clip, Charles meets Liam, an escaped convict who is attempting to travel over the Blue Mountains to the west. Discover Ask students to research the reasons why Australia was selected as the site of a British penal colony. They should also find out who was sent to the colony and where the convicts were first incarcerated. Refer to the My Place for Teachers, Decade timeline – 1800s for an overview. Students should write an account of the founding of the penal settlement in New South Wales. As a class, discuss the difficulties convicts faced when escaping from an early Australian gaol. Examine the reasons they escaped and the punishments inflicted when they were captured. List these reasons and punishments on the board or interactive whiteboard. For more in-depth information, students can conduct research in the school or local library, or online. -

31 July 2020 Fremantle Prison Celebrates 10 Years As Perth's Only World Heritage Listed Site. Fremantle Prison Will This Week

31 July 2020 Fremantle Prison celebrates 10 years as Perth’s only World Heritage Listed Site. Fremantle Prison will this week celebrate the 10th anniversary of their World Heritage listing as part of the Australian Convict Sites. Inscribed on the prestigious World Heritage List on 31 July 2010, the Australian Convict Sites, which includes 11 properties from around Australia, tell an important story about the forced migration of over 168,000 men, women and children from Britain to Australia during the late 18th and 19th centuries. Fremantle Prison Heritage Conservation Manager, and current Chair of the Australian World Heritage Advisory Committee, Luke Donegan, said, “Fremantle Prison is a monument to the development of Western Australia as we know it today.” “It is the most intact convict-built cell range in the nation and was the last convict establishment constructed in Australia.” The Australian Convict Sites World Heritage Property also includes Cockatoo Island Convict Site, Sydney, NSW (1839–69); Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney, NSW (1819–48); Kingston and Arthur’s Vale Historic Area, Norfolk Island (active 1788–1814 and 1824–55); Old Government House and Domain, Parramatta Park, NSW (1788– 1856); and the Old Great North Road, Wiseman’s Ferry, NSW (1828–35). Brickendon-Woolmers Estates, Longford (1820–50s); Darlington Probation Station, Maria Island National Park (1825–32 and 1842–50); Cascades Female Factory, Mount Wellington (1828–56); Port Arthur Historic Site, Port Arthur (1830–77); and Coal Mines Historic Site, Norfolk Bay (1833–48). Fremantle Prison marks the place where the practice of forced migration through transportation ceased with the arrival of the convict ship Hougoumont in January 1868, and is an essential part of the Australian convict story.