Download PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visit All of the Historic Sites and Museums! Ohiohistory.Org

Visit all of the historic sites and museums! ohiohistory.org ohiohistory.org • 800.686.6124 35. Fort Ancient Earthworks & Nature Preserve Museum/ Historic Buildings Mounds/ Monument/ Natural Area/ Gift Picnicking NORTHEAST Site Name Restrooms Average Visit 6123 State Route 350, Oregonia 45054 • 800.283.8904 v 190910 Visitor Center Open to Public Earthworks Gravesite Trails (miles) Shop (*shelter) Explore North America’s largest ancient hilltop enclosure, built 15. Custer Monument 1 Armstrong Air & Space Museum 2+ hours 2,000 years ago. Explore an on-site museum, recreated American State Route 646 and Chrisman Rd., New Rumley • 866.473.0417 Indian garden, and miles of hiking trails with scenic overlooks. 2 Cedar Bog Nature Preserve 1 2+ hours Visit the site of George Armstrong Custer’s birthplace and see the monument to the young soldier whose "Last Stand" made him a 36. Fort Hill Earthworks & Nature Preserve 3 Cooke-Dorn House 1 1+ hours household name. 13614 Fort Hill Rd., Hillsboro 45133 • 800.283.8905 Visit one of the best-preserved American Indian hilltop enclosures Ohio. of 4 Fallen Timbers Battlefield Memorial Park 1+ hours 16. Fort Laurens in North America and see an impressive variety of bedrock, soils, 11067 Fort Laurens Rd. NW (CR 102), Bolivar 44612 • 800.283.8914 flora and fauna. history fascinating and varied the life to bring help to 5 Fort Amanda Memorial Park 0.25 * 1+ hours Explore the site of Ohio’s only Revolutionary War fort, built in 1778 groups local these with work to proud is Connection 37. Harriet Beecher Stowe House History Ohio The communities. -

1984 – Present 2018 Summer 2018: Rising Water, Rising Challenges – Elevating Historic Buildings out of Harm’S Way

National Alliance of Preservation Commissions The Alliance Review Index: 1984 – Present 2018 Summer 2018: Rising Water, Rising Challenges – Elevating Historic Buildings Out of Harm’s Way • Resilience in Annapolis – Creating a Cultural Resource Hazard Mitigation Plan – Lisa Craig, Director of Resilience at Michael Baker International • Design Guidelines for Elevating Buildings – The Charleston Process – Dennis J. Dowd, Director of Urban Design and Preservation/City Architect for the City of Charleston • Rising Waters – Raising Historic Buildings – Christopher Wand, AIA • Challenges on the Coast – Flood Mitigation and Historic Buildings – Roderick Scott, Certified Flood Plain Manager, Louisette Scott, Certified Flood Plain Manager and Planning Director in Mandeville, LA • Past Forward 2018 Presentation Conference – Next Stop, San Francisco – Collen Danz, Forum Marketing Manager in the Preservation Division of the National Trust for Historic Preservation • Staff Profile: Joe McGill, Founder, Slave Dwelling Project □ State News o Florida: “Shotgun houses and wood-frame cottages that were once ubiquitous in the historically black neighborhood of West Coconut Grove are fast disappearing under a wave of redevelopment and gentrification.” o North Carolina: “The Waynesville Historic Preservation Commission has made it possible for area fourth graders to have a fun way to get to know their town’s history.” o Oregon: “About half of the residents of Portland’s picturesque Eastmoreland neighborhood want the neighborhood to be designated a historic -

ALCWRT May 2019

Volume 19, Issue 5 MAY - 2019 ABOUT the ALCWRT Dr. CURT FIELDS will be the featured speaker for the MAY 16th meeting of the Abraham Lincoln Civil War Round Table. The Abraham Lincoln Civil War Round Table is the oldest Civil War ULYSSES S. GRANT: THE MAN BEHIND THE UNIFORM Round Table in Michigan, founded When someone mentions U.S. Grant, you may first think of his military in 1952. Our JUBILEE (65th) anniversary was September, 2017. achievements in the Civil War. Or maybe you think of his years as the 18th President of the United States. But when you attend the Meetings are each 3rd Thursday, ALCWRT’s May meeting and meet Living Historian Dr. Curt Fields, September through May you’ll learn more about Grant’s childhood, his years at the US Military (except December), 7:30 pm, at the Academy, his courtship and marriage to Julia, his service in the Mexican Charter Township of Plymouth City War, his resignation from the army in the 1850’s, and his struggles in Offices, 9955 N. Haggerty, in the his civilian endeavors. Dr. Fields will present all this and more in his Chamber Council Room. th first person portrayal as Grant at our May 16 meeting. For more information, contact ******************************************************************** ALCWRT President Liz Stringer at Dr. CURT FIELDS is an avid and lifelong student of the American Civil [email protected] War, through which he developed his deep respect and admiration for General Grant. Fields is also the same height and body type as Grant, Our web site is ALCWRT.org which makes his portrayals quite convincing and true-to-life. -

OQ Fall 2016

QUARTERLY FALL 2016 | VOL. 59 NO. 4 Collecting, Preserving, and Celebrating Ohio Literature Fall 2016 | 1 Contents QUARTERLY FALL 2016 STAFF FEATURES David Weaver..............Executive Director Stephanie Michaels.....Librarian and Editor 4 Mother of Presidents: Kathryn Powers...........Office Manager BOARD OF TRUSTEES Ohio's Presidential History EX-OFFICIO 10 2016 Ohioana Awards Karen Waldbillig Kasich, Westerville ELECTED 14 In the Memory of the Living President: Daniel Shuey, Westerville Vice-President: John Sullivan, Plain City 2016 Walter Rumsey Marvin Grant Winner Secretary: Geoffrey Smith, Columbus Treasurer: Lisa Evans, Johnstown 22 Author Interview: Candice Millard Gillian Berchowitz, Athens Rudine Sims Bishop, Columbus Helen F. Bolte, Columbus Ann M. Bowers, Bowling Green BOOK REVIEWS Georgeanne Bradford, Cincinnati Christopher S. Duckworth, Columbus Bryan Loar, Columbus 24 Nonfiction Louise S. Musser, Delaware Claudia Plumley, Columbus 27 Fiction Cynthia Puckett, Columbus Joan V. Schmutzler, Berea 29 Young Adult David Siders, Cincinnati Robin Smith, Columbus 29 Middle Grade & Children’s Yolanda Danyi Szuch, Perrysburg Jacquelyn L. Vaughan, Dublin Jay Yurkiw, Columbus BOOKS AND EVENTS APPOINTED BY THE GOVERNOR Carl J. Denbow, Ph.D., Athens Carol Garner, Mount Vernon 31 Book List H.C. "Buck" Niehoff, Cincinnati 38 A Legacy of Caring EMERITUS Frances Ott Allen, Cincinnati Christina Butler, Columbus 39 Coming Soon John Gabel, Avon Lake James M. Hughes, Dayton George Knepper, Stow Robert Webner, Columbus The Ohioana Quarterly (ISSN 0030-1248) is currently published four times a year by the Ohioana Library Association, 274 East First Avenue, Suite 300, Columbus, Ohio 43201. Individual subscriptions to the Ohioana Quarterly are available through membership in the Association; $35 of membership dues pays the required subscription. -

August 2021 Issue

AUGUST 2021 ISSUE News for the members of OLLI at The University of Alabama in Huntsville Wilson Hall Room 111, Huntsville, AL 35899 | 256.824.6183 | [email protected] | Osher.uah.edu AUGUST - SEPTEMBER 2021 Sign up for each event by clicking “online.” All online bonuses/events are through Zoom video conferencing. You will receive an email with the Zoom meeting invitation one business day prior. There is a limited capacity per event. Aug 10 | Tue | 10:00 am | In Person Event: Fall Open House Come back to campus to register for our fall term! Join us to see fellow OLLI members in-person while learning more about our upcoming courses, bonuses, and events. Sept 8 | Wed | 4:00 pm | In Person Presented by OLLI Curriculum Committee OLLI Annual Meeting It’s time to celebrate OLLI's accomplishments from the last two years! Join us for a fun afternoon with fellow Aug 20 | Fri | 9:00 am | Online/In Person members on Wednesday, September 8 at Event: OLLI Day Alabama 4:00 pm. Meet UAH President, Dr. Darren Dawson, and Join us to celebrate the 2nd OLLI Day Alabama! Together learn about UAH updates and upcoming projects. Wish with the OLLI programs at The University of Alabama and Dr. Karen Clanton well in her retirement, celebrate the Auburn University, we will have a daylong celebration with winners of the OLLI Photo Contest, and participate in many notable speakers. Register and find more details at the recognition of the Volunteer of the Year and Legacy Osher.uah.edu/OLLIDayAlabama Volunteer award recipients. -

HARDTACK June 2007

1 HARDTACK Indianapolis Civil War Round Table Newsletter http://indianapoliscwrt.org/ June 11, 2007 at 6:30 p.m. Meeting at Primo Banquet and Conference Center, 5649 Lee Road The Plan of the Day “I Am Too Late” Joseph Johnston and the Fall of Vicksburg As Vicksburg slowly succumbed to the ever-tightening grip of Federal forces that laid siege to the city in the summer of 1863, Southern civil and military authorities looked to Gen. Joseph E. Johnston to rescue the “Gibraltar of the Confederacy” and its garrison. The force that he assembled in the Jackson-Canton area, fifty miles east of Vicksburg, eventually swelled to 31,000 men and was called the Army of Relief. Coupled with the 30,000-man army in Vicksburg under Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, Confederate forces gained a brief period of numeric superiority. But despite the desperate situation in Vicksburg or the urgings of President Jefferson Davis and Secretary of War James A. Seddon, Johnston remained immovable and the window of opportunity closed when Union reinforcements arrived by the tens of thousands. With the fate of the nation and his own reputation in the balance, Johnston finally moved, but by then it was too late. On July 4, the fortress city on the Mississippi River surrendered, which sealed the fate of the Confederacy. Most works on the Vicksburg campaign, however, only touch on Joseph E. Johnston and the activities of the Army of Relief. Our June speaker, Terry Winschel, is the long-serving historian at Vicksburg National Military Park. His program will examine the controversial service of Joseph E. -

February Speaker

______________________________________________________________________________ CCWRT February, 2017 Issue Meeting Date: February 16, 2017 Place: The Drake Center (6:00) Sign-in and Social (6:30) Dinner (7:15) Business Meeting (7:30) Speaker Dinner Menu: Chicken Piccata, Caesar Salad, Macaroni & Cheese, Fresh Asparagus, and Italian Cream Cake Vegetarian Option: Upon request Speaker: Mark Lause, University of Cincinnati Topic: Sterling Price and the 1864 Missouri Campaign ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Reservations: If you do not have an Automatic Reservation, please remember to submit your meeting reservation to the web site at http://cincinnaticwrt.org/wordpress/contact/rsvp/ or call it in to Dave Stockdale at 513-310-9553. Leave a message, if necessary. If you are making a reservation for more than yourself, please provide the names of the others. Please note that all reservations must be in no later than 8:00 pm Wednesday, February 8, 2017. _______________________________________________________________________________________ February Speaker: As the Civil War was drawing to a close, former Missouri governor Sterling Price led his army on one last desperate campaign to retake his home state for the Confederacy, part of a broader effort to tilt the upcoming 1864 Union elections against Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans. In The Collapse of Price’s Raid: The Beginning of the End in Civil War Missouri, Mark A. Lause examines the complex political and social context of what became known as “Price’s Raid,” the final significant Southern operation west of the Mississippi River. 1 ©2017 The Cincinnati Civil War Round Table The success of the Confederates would be measured by how long they could avoid returning south to spend a hungry winter among the picked-over fields of southwestern Arkansas and northeastern Texas. -

Capital Budget Analysis Table of Contents

Ohio Legislative Service Commission Legislative Budget Office Capital Item Analysis Capital Appropriations (FY 2021-FY 2022) December 17, 2020 Introduction This report is an analysis of the capital appropriations in S.B. 310 of the 133rd General Assembly. S.B. 310 appropriates just under $2.13 billion in new capital appropriations for the biennium ending June 30, 2022, and authorizes about $1.75 billion in new debt. The report contains a number of summary reports which break down S.B. 310's capital appropriations by fund and agency, list all new debt authorizations, list all projects by county, and list only community projects by county. These summary reports are followed by a detailed analysis that provides a description of each capital appropriation. The 133rd General Assembly made additional new capital appropriations in S.B. 4, effective October 13, 2020. S.B. 4 appropriates $555.0 million in new capital appropriations for the biennium ending June 30, 2022, and authorizes $525.0 million in new debt. An analysis of the capital appropriations and new debt authorizations in S.B. 4 may be found in LSC's fiscal note for that bill. Including both S.B. 310 and S.B. 4, the 133rd General Assembly’s capital appropriations for new projects total approximately $2.68 billion. Total new debt authorizations amount to $2.28 billion. Legislative Service Commission Capital Budget Analysis Table of Contents Summary Reports Capital Appropriations by Fund 1 Capital Appropriations by Agency 2 Capital Appropriations by Fund and Agency 3 Capital Appropriations -

Experience BOUNTYROWN C2019 VISITORS GUIDE

Experience BOUNTYROWN C2019 VISITORS GUIDE BrOwn cOunty AmericAs LegendAry OhiO’s generAL COVERED BICYCLE ROUTE JOHN HUNT BRIDGES TO FREEDOM HERITAGE TRAIL 2019 BROWN COUNTY TOURISM GUIDE 2 Welcome!Brown county, Ohio Visitor’s guides some highlights: history of georgetown, Ohio home of ulysses s grant....................................8 America’s Legendary Bicycle route to Freedom..................................................10 Land of grant..............................................................................................14 trails of Brown county....................................................................................22 2019 BROWN COUNTY TOURISM GUIDE 3 GUIDE TOURISM COUNTY BROWN 2019 EXPERIENCE BROWN COUNTY, OHIO SOON! Nestled along the banks of the Ohio River and extending north almost to Warren County, Brown County, Ohio is rich with history and activities. Take a stroll through downtown Ripley and enjoy the sights of the Ohio River. Visit key points of historical interest including stops along the Underground Railroad in Ripley and the Ulysses S. Grant boyhood home in Georgetown. Shop along George- town’s Merchants Row and then enjoy dinner and a bottle of wine at a local winery. Take a lovely country drive to visit one of our many covered bridges or quilt barns. Brown County, Ohio has a lot to offer. Brown County is a rural, agricultural community with beautiful scenery, great hunting and fishing, fun on the Ohio River, rich historical sites and warm people. We welcome you to explore our county and discover all of the variety of wonderful things it has to offer. BROWN COUNTY OHIO TOURISM INC. MEMBERS Nancy Montgomery Sonja Cropper Betty Campbell Nancy Purdy Stan Purdy Carol Stivers Joyce Tull Follow us at www.experiencebrowncountyohio.com or on Facebook at Experience Brown County Ohio Visit Historic Georgetown, Ohio Founded 1819 Ulysses S. -

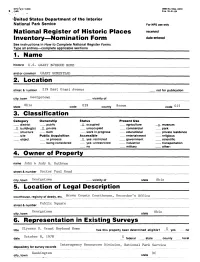

National Register of Historic Places Inventory

NPS Fgrm 10-900 OMB NO. 1024-0018 * (3-82) ' Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For Nps use omy National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections _____________________ 1. Name historic U.S. GRANT BOYHOOD HOME and or common GRANT HOMESTEAD 2. Location street & number East Grant Avenue not for publication city, town Georgetown vicinity of Ohio state code 039 county Brown code 015 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture X rnuseum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name John & Judy A. Ruthven street & number Doctor Faul Road city, town Georgetown vicinity of state Ohio 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Brown County Courthouse, Recorder's Office Public Square street & number Georgetown city, town state Ohio 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Ulysses S. Grant Boyhood Home has this property been determined eligible? __! _ yes __ no October 8, 1978 date X federal _ state county local Interagency Resources Division, National Park Service depository for survey records Washington DC city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered x original site good ruins X altered _ moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The original section of the house is a two-story, brick structure facing onto Water Street, built in 1823, by Jesse R. -

CHARGER, May 2013

THE CLEVELAND CIVIL WAR ROUNDTABLE THE CHARGER ! May 2013 496th Meeting Vol. 34, #9 Tonight’s Program: Tonight’s Speaker: Lincoln Harold Holzer "Now he belongs to the ages," Secretary of War Harold Holzer is Vice President for External Affairs, Edwin Stanton famously declared moments after our Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and one of the sixteenth president had drawn his last breath. country's leading authorities on the political culture of the Posterity has abundantly fulfilled Stanton's Civil War era and Abraham Lincoln. A prolific writer and prediction. Two centuries after his birth, Abraham lecturer, and frequent guest on television, Mr. Holzer Lincoln (1809-1865) has achieved an unrivaled served as co-chair of the United States Lincoln preeminence in American history, culture, and myth. Bicentennial Commission. Mr. Holzer has authored, co- The sudden shock of his death gave rise to authored, or edited over 25 books and has written more superlatives that took root and have been perennial than 350 articles for both popular magazines and scholarly in American letters ever since. Lincoln has been journals, including Life Magazine, American Heritage, variously considered our greatest president, our Civil War Times, American History Illustrated, North & greatest orator, the Great Emancipator; the foremost South, Blue & Gray, The Chicago Tribune, and The New exemplar of the vitality of the American frontier and York Times, and recently served as a consultant on the the promise of American democracy; the central Steven Spielberg movie, Lincoln. actor in the Civil War, our greatest national drama; our most tragic statesman, whose martyrdom has become inextricably linked to his own incandescent Date: Wednesday, vision of our national redemption. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory — Nomination Form Date Entered 1. Name 2. Location 3. Classification 4. Owner O

NPS Fdrrn 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) ' Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places Inventory — Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries — complete applicable sections 1. Name historic U.S. GRANT BOYHOOD HOME and or common GRANT HOMESTEAD 2. Location street & number 219 East Grant Avenue not for publication city, town Georgetown vicinity of state Ohio code ° 39 county Brown code ° 15 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture . x rnuseum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name John & Judy A. Ruthven street & number Doctor Faul Road city, town Georgetown __ vicinity of state Ohio 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Brown Courthouse, Recorder's Office Public Square street & number Georgetown Ohio city, town state 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Ulysses S. Grant Boyhood Home title has this property been determined eligible? X yes no October 8, 1978 X date federal state county local Interagency Resources Division, National Park Service depository for survey records Washington DC city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one _5 excellent __ deteriorated _.__ unaltered ? original site __ good __ ruins _X altered .._._ moved date __ fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The original section of the house is a two-story, brick structure facing onto Water Street, built in 1823, by Jesse R.