Culture, Value and Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’S Built Heritage 410062 789811 9

Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’s Built Heritage Today, Singapore stands out for its unique urban landscape: historic districts, buildings and refurbished shophouses blend seamlessly with modern buildings and majestic skyscrapers. STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS This startling transformation was no accident, but the combined efforts of many dedicated individuals from the public and private sectors in the conservation-restoration of our built heritage. Past, Present and Future: Conserving the Nation’s Built Heritage brings to life Singapore’s urban governance and planning story. In this Urban Systems Study, readers will learn how conservation of Singapore’s unique built environment evolved to become an integral part of urban planning. It also examines how the public sector guided conservation efforts, so that building conservation could evolve in step with pragmatism and market considerations Heritage Built the Nation’s Present and Future: Conserving Past, to ensure its sustainability through the years. Past, Present “ Singapore’s distinctive buildings reflect the development of a nation that has come of age. This publication is timely, as we mark and Future: 30 years since we gazetted the first historic districts and buildings. A larger audience needs to learn more of the background story Conserving of how the public and private sectors have creatively worked together to make building conservation viable and how these efforts have ensured that Singapore’s historic districts remain the Nation’s vibrant, relevant and authentic for locals and tourists alike, thus leaving a lasting legacy for future generations.” Built Heritage Mrs Koh-Lim Wen Gin, Former Chief Planner and Deputy CEO of URA. -

Building Edge

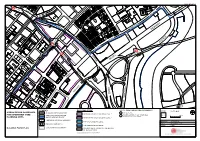

J V A N IC L T T M A O A A R E Y L I J O A E A H APPENDIX 3-1 L N T A R A R C N O A S C J T N T N R R S A O E K C E L L C T J A H A C P D A L A A X" O A O R R R L N A A R O B N K E U C A B R J O D O A D H D C R C A L R O RO A A 12 R N A T O E L L K G I NA L W O E A A A E D C C T J I C A E L D S A D R B E L E R L R OR E T A K E CH R N B T R RO R S (!52 T E P C T I S E S 20 T J A A N N L G E A C E IA N 12 4 U K (!70 7 A C (! Q R P IN C N O A D S 4 R N A T T T G H H R E O T A E Y C C R E E 4 O T I R A T A C C T S H R P S E S E 20 V O U R T T M T T C W R H H S U E S N EE A I S E 20 O R (!14 TR H T 4 * 4 C U S L E T S L G T R S T T B I E R T A G E E B R N C N A H E U C E A R T S E H C 4 4 S T A P C T O P N 16 T A T R C E E S E A C S U R A M T H G S 4 S 20 R A J IN A T T A B M E E V R A E C L TR A P 20 R L S C C 4 H B A A J 16 K O I L R IN I D E L 16 O 20 A A B D U H U D L S C D A 16 A C S G 4 B R N S A N E A O D E N E T B N L C 4 S O R R O 16 O O I A R O O L E H E L M C E G A C A E N * N N D E C S I E U T V D B T B A 16 L D IN L K E 4 20 C X" 16 * C H H E C N C T N A G T E E E Y E L A E B E N R O 16 R P T L S " T X A Y O S C A E R W C E H S IG N 12 A H R 16 16 X"B R L E F OL B O U O L IC T A M G L N * A P E D N IS O E IL T H 12 R 16 A IC T E I 4 S S E R R N C 12 16 T DT O I R A A T N C L 4 16 O S Q H B C R U O O E C U O E R L L R C IA L P N A E !51 G N T ( C E A M S S 4 T R W 16 ID E R N A E 16 D H E R E C C T E L S O * C E T U R A Q E D D TANJONG RHU VIEW * E 4 T A O 16 E R 16 B A I G N D R S I O C A TR * I E R A E D R T B O 16 T M P S IL -

Jubilee Walk Marks Key Milestones of Our Nation-Building and Is a Lasting Physical Legacy of Our Golden Jubilee Celebrations

Launched in 2015 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Singapore’s independence, the Jubilee Walk marks key milestones of our nation-building and is a lasting physical legacy of our Golden Jubilee celebrations. It is a collaborative effort across various agencies, including Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth, National Heritage Board, National Parks Board and Urban Redevelopment Authority. JUBILEE In celebration of WALK 1 INTRODUCTION The story of Singapore and her people has always been one of resilience amid change. From the early pioneers who came to make a living, to later generations who overcame the war and struggled to build a modern, sovereign nation, Singapore’s success over the past 50 years owes much to the indomitable spirit, fortitude and resourcefulness of her people. National Day Parade, 2015 This national resilience continues to be a hallmark of independent Singapore. It has allowed the nation to weather periods of crisis, defend and strengthen herself on all fronts, and for her people to work together to transform the island into a global hub for commerce and culture. Today, this same Singapore spirit is driving a new phase of development as the nation strives to create a liveable and sustainable city; a home like no other with ample room to grow and opportunities for different communities to fl ourish and build a better future together. This collective resilience, which defi nes Singapore’s journey from 14th century trading hub, to colonial port to independent nation and global city, is the theme of the Jubilee Walk. Created in 2015 to mark Singapore’s Golden Jubilee, the Jubilee Walk is a specially curated trail of iconic locations that recall Singapore’s historic beginnings, her path towards nationhood, and show the way forward to Singapore’s present and future as a global city. -

Circular No : URA/PB/2019/18-CUDG Our Ref : DC/ADMIN/CIRCULAR/PB 19 Date : 27 November 2019

Circular No : URA/PB/2019/18-CUDG Our Ref : DC/ADMIN/CIRCULAR/PB_19 Date : 27 November 2019 CIRCULAR TO PROFESSIONAL INSTITUTES Who should know Developers, building owners, architects and engineers Effective Date With immediate effect UPDATED URBAN DESIGN GUIDELINES AND PLANS FOR URBAN DESIGN AREAS 1. As part of the Master Plan 2019 gazette, URA has updated the urban design guidelines and plans applicable to all Urban Design Areas as listed below: a. Downtown Core b. Marina South c. Museum d. Newton e. Orchard f. Outram g. River Valley h. Singapore River i. Jurong Gateway j. Paya Lebar Central k. Punggol Digital District l. Woodlands Central 2. Guidelines specific to each planning area have been merged into a single set of guidelines for easy reference. To improve the user-friendliness of our guidelines and plans, a map-based version of the urban design guide plans is now available on URA SPACE (Service Portal and Community e- Services). 3. All new developments, redevelopments and existing buildings undergoing major or minor refurbishment are required to comply with the updated guidelines. 4. The urban design guidelines provide an overview of the general requirements for developments in the respective Urban Design Areas. For specific sites, additional guidelines may be issued where necessary. The guidelines included herewith do not supersede the detailed guidelines issued, nor the approved plans for developments for specific sites. 5. I would appreciate it if you could convey the contents of this circular to the relevant members of your organisation. You are advised to refer to the Development Control Handbooks and URA’s website for updated guidelines instead of referring to past circulars. -

The Peranakan Collection and Singapore's Asian Civilisations Museum Helena C. Bezzina a Thesis Submitted

Nation Building: The Peranakan Collection and Singapore’s Asian Civilisations Museum Helena C. Bezzina A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy College of Fine Arts New South Wales University March 2013 1.1.1THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES 1.1.2Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Bezzina First name: Helena Other name/s: Concetta Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: School: Art History and Art Education Faculty: Collage of Fine Art (COFA) Title: Nation Building: The Peranakan Collection and Singapore’s Asian Civilisations Museum This case-study investigates whether it is valid to argue that the museological practices of the Asian Civilisations Museum (ACM), as manifested in the exhibition The Peranakan Legacy (1999–2006) and in the subsequent Peranakan museum (2008 to present), are limited to projecting officially endorsed storylines, or whether the museum has been able to portray multiple stories about the Peranakan community and their material culture. Drawing on Pierre Bourdieu’s theoretical framework, the study considers the genesis and context of the ACM within the social structures in which it operates. This approach allows for consideration of the generative reproduction of Singapore’s colonial structures, such as the prevailing doxa on race, manifested in the organising principle of the ACM’s Empress Place Museum with its racially defined galleries addressing Chinese, Malay/Islamic and Indian ancestral cultures. Analysing the ACM as a field in which the curatorial team (informed by their habitus) in combination with various forms of capital are at play, exposes the relationships between macro structures (state policy and economic drivers) and the micro operations (day-to-day decisions of the curatorial team at work on Peranakan exhibitions). -

The Old Hill Street Police Station Stands Today As MICA Building, the Headquarters of the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts

1st Window Page 1 Title: A Time and A Place : History of the Site Intro text: The Old Hill Street Police Station stands today as MICA Building, the headquarters of the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. Although built as a police station and barracks, the building’s significance lies in the history of the site, which was once associated with entertainment and education. It was here, between 1845 and 1856, that the Assembly Rooms, a space for public functions and a building that housed a theatre as well as a school, once stood. After the Rooms were demolished, a temporary theatre was built where amateurs performed till 1861. The performances at the theatre were to raise funds for the scenery, costumes and properties for a new theatre at the new Town Hall at another location; this would eventually become the present Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall, a place of the performing arts. It seems that the arts have never been far from the Old Hill Street Police Station, whether in time, association or distance. 1836 map 1854 map 1857 map 1862 map 1868 map Page 2 (1836 map) As shown in this 1836 map, the site of the Old Hill Street Police Station was vacant in the 1830s. Some sources have stated that this was the site of Singapore’s first jail though others have cited a temporary prison at the “end of the east bank of the river, close to where the stone landing steps are now.” This is likely to be where Empress Place stands at present. -

Singapore River Walk

The Singapore River Walk takes you on a journey from Collyer Quay to » DISCOVER OUR SHARED HERITAGE Robertson Quay, focusing on the contributions of the river towards Singapore’s mercantile development through the various communities who lived and worked by the river, as well as the spectacular architecture SINGAPORE RIVER and social history of the bridges that criss-cross the river, facilitating the movement of people and goods across the river at various junctures. The Singapore River Walk is adopted by American Express. WALK For more information, visit Roots.sg Supported by Roadside hawkers along the Singapore River, 1970 Collyer Quay waterfront, 1960s STAMFORD ROAD Bus River HILL STREET CONTENTS LO MRT KE YEW STREE BUS Stop Taxi BUS 04143 STAMFORD ROAD T THE SINGAPORE RIVER WALK: AN INTRODUCTION p. 1 Roads Prominent Sites BUS A HARBOUR OF HISTORY: THE SINGAPORE RIVER THROUGH TIME p. 3 Parks Heritage Sites 04111 A 14th century port and kingdom Marked Sites BUS An artery of commerce: The rise of a global port of trade River 04142 A harbour and home: Communities by the river Walkways Of landings and landmarks: The river’s quays, piers and bridges BUS A river transformed: Creating a clean and fresh waterway 04149 BUS 04167 RIV FORT AD POINTS OF ARRIVAL: THE QUAYS OF THE SINGAPORE RIVER p. 7 ER VALLEY R EET O Boat Quay CANNING Clarke Quay PARK E R BUS River House 04168 North Boat Quay and Hong Lim Quay LIANG COURT OA HILL STR Read Street and Tan Tye Place D Robertson Quay H B R I DG Ord Bridge RT Alkaff Quay and Earle Quay US Robertson B BUS NO , 04219 Y Quay 04223 R Whampoa’s OLD HILL COMMERCE ON THE WATERFRONT p. -

Our Geylang Serai Museology Highlight

THE STORIES BEHIND JUBILEE WALK NO. COMMUNITY 32 HERITAGE TRAIL: VOL. OUR GEYLANG 09 SERAI ISS. 01 MUSEOLOGY HIGHLIGHT: WHEN OBJECTS BECOME THE SUBJECT Front Cover National Day, August 9, 1966 Photo courtesy of National Archives of Singapore Front Inner Cover Mummy-board, probably from Thebes, Egypt, 950 – 990 BC © 2015 the Trustees of the British Museum FOREWORD FOREWORD Publisher National Heritage Board 61 Stamford Road, MUSE SG is beginning the of the Singaporean identity. The #03-08, Stamford Court, New Year with a new look and a new generation highlights our Singapore 178892 look back on Singapore’s Jubilee multi-faceted cultural identity, Chief Executive Officer Celebrations. continuing the thread of our Rosa Daniel past as a heterogeneous mix of A key milestone in the Jubilee Assistant Chief Executive immigrants who called Singapore Alvin Tan Year, the Jubilee Walk was home. They remind us that we are (Policy & Community) launched to commemorate the only as strong as we are resolute in 50th anniversary of Singapore’s creating a better future together, MUSE SG team independence. The Jubilee Walk while keeping the roots of our Editor-in-chief covers 23 architectural gems, beginnings close. David Chew bringing visitors up close and Design Consultant personal with Singapore’s past, Finally, to round up the year Ian Lin present and future. and usher in new beginnings, we Editorial Managers remember that history also lies in Reena Devi MUSE profiles 12 individuals Ruchi Mittal our diverse communities all over Raudha Muntadar for The Stories behind the Jubilee the island and, for this issue, we Production Manager Walk (page 27) in this bumper focus on Geylang Serai. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Cover Page Preface Part 1 General Considerations 1. Planning Areas & Master Plan 2. Macro Considerations 3. Micro Considerations 4. Special Requirements Part 2 Types of Development 1. Commercial Developments 2. Hotel & other Accommodation Facilities 3. Industrial / Warehouse / Utilities / Tele-communication / Business Park Developments 4. Place of Worship & Institutional Developments 5. Other Uses Part 3 The Guidelines at a Glance The Guidelines at a Glance Geylang Urban Design Guidelines (GUDG) 1 As at February 2019 DEVELOPMENT CONTROL PARAMETERS FOR NON-RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT This handbook is subject to revision from time to time. Nothing herein shall be construed to exempt the person submitting an application or any plans from otherwise complying with the provisions of the Planning Act (Cap 232, I998 Ed) or any rules and/or guidelines made thereunder or any Act or rules and/or guidelines for the time being in force. While every endeavour is made to ensure that the information provided is correct, the Competent Authority and the Urban Redevelopment Authority disclaim all liability for any damage or loss that may be caused as a result of any error or omission. Important Note: You are advised not to print any page from this handbook as it is constantly updated. URBAN REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY Back to Main 2 PREFACE The Development Control Group of the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) plays an important role in guiding and facilitating the physical development of Singapore. As part of URA’s on-going efforts to provide efficient and pleasant service to the public to facilitate property development, it has produced a series of handbooks on development control to inform and guide the public on the procedures in submitting development applications. -

Friends of the Museums Singapore September / October 2019 Art

Friends of the Museums Singapore September / October 2019 art history culture people President's Letter Dear Friends, Welcome back to all our members who were travelling over the summer months. I hope you had a rejuvenating time with your friends and families or simply a great vacation. While many docents were travelling, those who were in town took on multiple tours to ensure we met all our guiding commitments. And a special word of thanks to the Malay Heritage Centre and Asian Civilisations Museum docents for training local schoolchildren to give them a taste of what it is like to be a museum guide. FOM docent training commences on 17 September. Over the past few months our training teams have been working hard to line up interesting lectures, activities and field trips for the upcoming sessions. If you are thinking of training to be a volunteer museum guide or docent, please get in touch with us. Spaces are still available at some of the museums. Join us on 2 September for our Open Morning at 10:00 am at the Asian Civilisations Museum. FOM’s activity group leaders and members will be on hand to share the many interesting programmes they have planned for the coming months. You might find an activity that you want to explore further. FOM Book Groups are planning a book swap so remember to bring along books to exchange. The Open Morning will be followed by a lecture at 11:00 am. The speaker for the day will be Patricia Bjaaland Welch, an expert on Chinese art and symbolism in art. -

Singapore River Bridges and the Padang to Be Gazetted As National Monuments

MEDIA RELEASE For immediate release SINGAPORE RIVER BRIDGES AND THE PADANG TO BE GAZETTED AS NATIONAL MONUMENTS Cavenagh Bridge, one of the three Singapore River The Padang in 1966 where the first National Day Bridges that will be collectively gazetted. Parade was held. Credit line: Photo courtesy of National Heritage Credit line: Ministry of Information and the Arts Board collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore Singapore, 3 August 2019 – Singapore will welcome two new National Monuments – the Singapore River Bridges (Cavenagh, Anderson and Elgin Bridges) and the Padang. With the upcoming gazettes, the bridges and the Padang will be accorded the highest level of preservation in view of their national significance. The National Heritage Board’s (NHB) intention to gazette the National Monuments was announced by Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat today. The announcement was made to commemorate Singapore’s Bicentennial this year, in light of the significance that the Singapore River Bridges and the Padang have to our growth and development as a nation. 2 Ms Jean Wee, Director of the Preservation of Sites and Monuments division, NHB, said, “The Padang and the Singapore River Bridges have been pivotal to Singapore’s early years. Cavenagh bridge is the oldest bridge to still span the river. The gazette of Cavenagh, Anderson and Elgin Bridges as an ensemble gives recognition to the technological advancements in early Page 1 of 14 bridge construction. Functionally, they supported Singapore’s expanding trade interests, as well as physically linked the commercial and government quarters. The Padang, an open space in the heart of the civic district, was the de facto town square of sorts. -

A CITY of CULTURE: PLANNING for the ARTS Culture Is Intricately Linked to Political, Economic, and Social Life

A CITY OF CULTURE: PLANNING FOR THE ARTS Culture is intricately linked to political, economic, and social life. A city’s culture is revealed from the way it is planned, built, and developed. Choices made by the city and its people indicate their values and what they care for, and contribute to the people’s sense STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS of identity and resilience over time. For a liveable city, planners and policymakers need to carefully consider the role and development of culture, and embed these considerations upfront in the urban planning process. This Urban Systems Study documents Singapore’s journey in shaping the urban development of culture and the arts. Throughout the years of Singapore’s independence, the arts has provided an avenue to promote national unity, diversify a fragile economy, and nurture creative talents to foster a more vibrant and gracious city. It has also faced its share of contestation, balancing global city ambitions with the needs of communities whom the city is for. This study charts the Planning for the Arts A City of Culture: development of strategies in urban planning and programmes for the A City of Culture: arts and culture sector, and illustrates how long-term planning and collaboration across stakeholders remain critical to the making of a Planning for city of culture. the Arts “ If you visit the great cities in the world – New York, Paris, Shanghai, London, Mumbai – you will find that arts and culture are an integral part of the cities…These cities are not just business or transportation hubs or dense conurbations of people.