Oxford Heritage Walks Book 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NR05 Oxford TWAO

OFFICIAL Rule 10(2)(d) Transport and Works Act 1992 The Transport and Works (Applications and Objections Procedure) (England and Wales) Rules 2006 Network Rail (Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements (Land Only)) Order 202X Report summarising consultations undertaken 1 Introduction 1.1 Network Rail Infrastructure Limited ('Network Rail') is making an application to the Secretary of State for Transport for an order under the Transport and Works Act 1992. The proposed order is termed the Network Rail (Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements (Land Only)) Order ('the Order'). 1.2 The purpose of the Order is to facilitate improved capacity and capability on the “Oxford Corridor” (Didcot North Junction to Aynho Junction) to meet the Strategic Business Plan objections for capacity enhancement and journey time improvements. As well as enhancements to rail infrastructure, improvements to highways are being undertaken as part of the works. Together, these form part of Oxford Station Phase 2 Improvements ('the Project'). 1.3 The Project forms part of a package of rail enhancement schemes which deliver significant economic and strategic benefits to the wider Oxford area and the country. The enhanced infrastructure in the Oxford area will provide benefits for both freight and passenger services, as well as enable further schemes in this strategically important rail corridor including the introduction of East West Rail services in 2024. 1.4 The works comprised in the Project can be summarised as follows: • Creation of a new ‘through platform’ with improved passenger facilities. • A new station entrance on the western side of the railway. • Replacement of Botley Road Bridge with improvements to the highway, cycle and footways. -

Ttu Mac001 000057.Pdf (19.52Mb)

(Vlatthew flrnold. From the pn/ture in tlic Oriel Coll. Coniinon liooni, O.vford. Jhc Oxford poems 0[ attfiew ("Jk SAoUi: S'ips\i' ani "Jli\j«'vs.'') Illustrated, t© which are added w ith the storv of Ruskin's Roa(d makers. with Glides t© the Country the p©em5 iljystrate. Portrait, Ordnance Map, and 76 Photographs. by HENRY W. TAUNT, F.R.G.S. Photographer to the Oxford Architectural anid Historical Society. and Author of the well-knoi^rn Guides to the Thames. &c., 8cc. OXFORD: Henry W, Taunl ^ Co ALI. RIGHTS REStHVED. xji^i. TAONT & CO. ART PRINTERS. OXFORD The best of thanks is ren(iered by the Author to his many kind friends, -who by their information and assistance, have materially contributed to the successful completion of this little ^rork. To Mr. James Parker, -who has translated Edwi's Charter and besides has added notes of the greatest value, to Mr. Herbert Hurst for his details and additions and placing his collections in our hands; to Messrs Macmillan for the very courteous manner in which they smoothed the way for the use of Arnold's poems; to the Provost of Oriel Coll, for Arnold's portrait; to Mr. Madan of the Bodleian, for suggestions and notes, to the owners and occupiers of the various lands over which •we traversed to obtain some of the scenes; to the Vicar of New Hinksey for details, and to all who have helped with kindly advice, our best and many thanks are given. It is a pleasure when a ^ivork of this kind is being compiled to find so many kind friends ready to help. -

Rare Plants Group 2009 Newsletter

Ashmolean Natural History Society of Oxfordshire Rare Plants Group 2009 Newsletter Birthwort, Aristolochia clematitis Photo: Charles Hayward www.oxfordrareplants.org.uk INTRODUCTION It was such a relief not to have a desperately wet summer in 2009 as the last two were, and what a joy when Creeping Marshwort came popping up in sheets on Port Meadow after an absence of 18 months. Photo 1(left): 1 June 2009. Port Meadow showing the flood-water retreating and mud flats exposed. Photo: Camilla Lambrick Photo 2 (right): 1 June 2009. Southern part of Port Meadow, a former Creeping Marshwort area, now drying mud. Graham Scholey of the Environment Agency and Rebecca Tibbetts of Natural England assess the situation. Photo: Camilla Lambrick Alas Fen Violet is still in trouble at Otmoor – perhaps not dry and warm early enough for this very early species. The Fen Violet exercised us most during 2009 by way of a meeting with specialists from Plantlife and Northern Ireland, in a nation-wide discussion of radical actions notably for introduction on RSPB land. True Fox-sedge looks to be well set-up for the future now that extensive introductions by BBOWT have proved successful. Other plants seem to get on well by themselves – Birthwort (see front cover picture and report on page 4) seems to be proliferating in the ditches of a medieval nunnery just north of Oxford city. Progress continues towards the Oxfordshire Rare Plants Register; photographs are being amassed, and thanks to Ellen Lee’s masterly command of the records we now have some 4000 new records beginning to take form as eye-catching maps. -

Historic Oxford Castle Perimeter Walk

Historic Oxford Castle 10 Plan (1878 Ordnance N Survey) and view of Perimeter Walk 9 11 12 the coal wharf from Bulwarks Lane, 7 under what is now Beat the bounds of Oxford Castle Nuffield College 8 1 7 2 4 3 6 5 Our new book Excavations at Oxford Castle 1999-2009 A number of the features described on our tour can be is available Oxford Castle & Prison recognised on Loggan’s 1675 map of Oxford. Note that gift shop and Oxbow: Loggan, like many early cartographers, drew his map https://www.oxbowbooks.com/ from the north, meaning it is upside-down compared to To find out more about Oxford modern maps. Archaeology and our current projects, visit our website or find us on Facebook, Twitter and Sketchfab: J.B. Malchair’s view of the motte in 1784 http://oxfordarchaeology.com @oatweet “There is much more to Oxford Castle than the mound and shops you see today. Take my tour to facebook.com/oxfordarchaeology ‘beats the bounds’ of this historic site sketchfab.com/oxford_archaeology and explore the outer limits of the castle, and see where excavations To see inside the medieval castle and later prison visit have given insights into the Oxford Castle & Prison: complex history of this site, that https://www.oxfordcastleandprison.co.uk/ has fascinated me for longer than I care to mention!” Julian Munby View towards the castle from the junction of New Road, 1911 2 Head of Buildings Archaeology Oxford Archaeology Castle Mill Stream Start at Oxford Castle & Prison. 1 8 The old Court House that looks like a N 1 Oxford Castle & Prison The castle mound (motte) and the ditch and Castle West Gate castle is near the site of the Shire Hall in the defences are the remains of the ‘motte and 2 New Road (west) king’s hall of the castle, where the justices bailey’ castle built in 1071 by Robert d’Oilly, 3 West Barbican met. -

Hirers' Instruction Manual Heyford Base

HIRERS’ INSTRUCTION MANUAL HEYFORD BASE BOATING INFORMATION & HANDOVER CERTIFICATES Please ensure that you bring this Manual with you on your holiday – your Handover Certificates are enclosed. (To print this document from your home printer, please select 2 pages to view per sheet. This document is set to A5 to reduce printing) 1 CONTENTS Page Welcome & Introduction 3 SECTION A – To be Read and Signed for before you Cast Off Our Commitment to You 4 Your Responsibilities 6 Safety on a Boating Holiday 9 What to do in Case of Accidents & Emergencies 12 Your Boat – How it Works, Daily Checks 14 Your Last Night on Board & Boat Return 17 Boat Acceptance Certificates 19 SECTION B – Useful Information Recommended Routes and Cruising Times 23 Northbound Southbound, including the Thames Water & Rubbish Points 27 Canalside Shops 28 Pubs & Restaurants 28 Places to Visit 28 Trouble-shooting Guide 30 Customer Comment Sheet 39 Please take the time to read everything in this booklet. We strongly recommend that you print/ keep a copy of this manual and bring it with you on your holiday – there is much useful information for you whilst cruising. We regret that we cannot be held responsible in any way for your holiday failing to meet your expectations if caused by failure to read our well-intentioned advice and recommendations… Please note that we will charge £2 should you arrive without this manual, or the Handover Certificates, to cover the printing costs of a replacement. 1. WELCOME ABOARD! Thank you for choosing to spend your holiday with us in the outstandingly pretty Cherwell Valley on the Cotswold borders. -

Uplands 06.01.2020

Democratic Services Reply to: Amy Barnes Direct Line: (01993) 861522 E-mail: [email protected] 20 December 2019 SUMMONS TO ATTEND MEETING: UPLANDS AREA PLANNING SUB-COMMITTEE PLACE: COMMITTEE ROOM 1, COUNCIL OFFICES, WOODGREEN, WITNEY DATE: MONDAY 6TH JANUARY 2020 TIME: 2.00 PM (Officers will be in attendance to discuss applications with Members of the Sub-Committee from 1:30 pm) Members of the Sub-Committee Councillors: Jeff Haine (Chairman), Geoff Saul (Vice-Chairman), Andrew Beaney, Richard Bishop, Mike Cahill, Nathalie Chapple, Nigel Colston, Julian Cooper, Derek Cotterill, Merilyn Davies, Ted Fenton*, David Jackson, Neil Owen and Alex Postan (*Denotes non-voting Member) RECORDING OF MEETINGS The law allows the council’s public meetings to be recorded, which includes filming as well as audio-recording. Photography is also permitted. As a matter of courtesy, if you intend to record any part of the proceedings please let the Committee Officer know before the start of the meeting. _________________________________________________________________ A G E N D A 1. Minutes of the meeting held on 2 December 2019 (copy attached) 2. Apologies for Absence and Temporary Appointments 3. Declarations of Interest To receive any declarations of interest from Councillors relating to items to be considered at the meeting, in accordance with the provisions of the Council’s Local Code of Conduct, and any from Officers. 1 4. Applications for Development (Report of the Business Manager – Development Management – schedule attached) Purpose: To consider applications for development, details of which are set out in the attached schedule. Recommendation: That the applications be determined in accordance with the recommendations of the Business Manager – Development Management. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Oxford Road Corridoor in Manchester Is Being Converted to a Pedes- Trian/Bus/Cycle Only Route, Despite Being a Major Traffic Route Into the City

Top: Grenoble Station has been redeveloped linked to a new office quarter. Middle: Cannes Station has incorporated all of the station functions as part of a traditional street scene. Bottom: Oxford Road Corridoor in Manchester is being converted to a pedes- trian/bus/cycle only route, despite being a major traffic route into the city. The area should be uniied by a pedestrian cycle network with ive new light bridges to create a web of routes that link a series of existing and new public spac- es as part of each of the sites. The University has released plans for the redevelopment of Osney Mead to transform the industrial estate into a knowledge park. This will include engineering, laboratories and a Oxford range of business space from start up accommodation to headquarter The Botley Road bridge under the builings. The plan also includes stu- railway is an impossible problem. C e n t r a l W e s t dent and graduate housing. The city could spend millions on the problem and it will still be substand- ard and the works themselves will cause gridlock. We suggest that cars are removed and the Botley Road is A new city quarter turned into a bus/pedestrian/cycle route (and potentially Oxford’s irst tram line) Osney Mead The station should be developed in stages as funding allows. The new platforms and through tracks will happen irst with each element linked to subsequent commercial development as part of a clear The masterplan that is integrated into Station the rest of the area. -

COUNCIL Monday 24 June 2013

COUNCIL Monday 24 June 2013 COUNCILLORS PRESENT: Councillors Sinclair (Lord Mayor), Brett (Deputy Lord Mayor), Abbasi (Sheriff), Altaf-Khan, Armitage, Baxter, Benjamin, Brown, Campbell, Canning, Clack, Clarkson, Cook, Coulter, Curran, Darke, Fooks, Fry, Goddard, Gotch, Haines, Hollick, Humberstone, Kennedy, Khan, Lloyd- Shogbesan, Lygo, McCready, Mills, O'Hara, Pressel, Price, Rowley, Royce, Sanders, Seamons, Simmons, Smith, Tanner, Turner, Van Nooijen, Williams and Wolff. 11. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Apologies for absence were received from Councillors Jones, Malik, Paule, Rundle and Wilkinson. 12. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST There were no declarations of interest from Councillors present at the meeting. 13. MINUTES (1) The Minutes of the Ordinary meeting of Council held on 22 nd April 2013 were agreed as a correct record and signed by the Lord Mayor. (2) The Minutes of the Annual meeting of Council held on 20 th May 2013 were agreed as a correct record and signed by the Lord Mayor. 14. APPOINTMENTS TO COMMITTEES There were no appointments to committees. 15. ANNOUNCEMENTS (1) Lord Mayor The Lord Mayor made four announcements as follows:- (a) A request to film the proceedings of Council had been received from a member of the public. Councillors discussed the request. Views ranged from noting that the meeting was filmed already and the outcome was placed on the Council’s website, through concern that private filming could result in extracts of that exercise being edited and used out of context to the view that council meetings should generally be fully opened to public scrutiny. The Lord Mayor noted that the request to film has only that day been received and the matter had not been discussed by the political groups. -

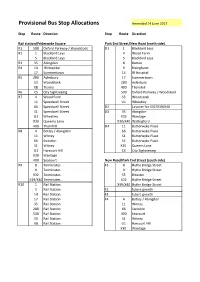

Provisional Bus Stop Allocations Amended 14 June 2017

Provisional Bus Stop Allocations Amended 14 June 2017 Stop Route Direction Stop Route Direction Rail station/Frideswide Square Park End Street/New Road (north side) R1 500 Oxford Parkway / Woodstock D1 1 Blackbird Leys R2 1 Blackbird Leys 4 Wood Farm 5 Blackbird Leys 5 Blackbird Leys R3 35 Abingdon 8 Barton R4 14 JR Hospital 9 Risinghurst 17 Summertown 14 JR Hospital R5 280 Aylesbury 17 Summertown S3 Woodstock 280 Aylesbury X8 Thame 400 Thornhill R6 CS City Sightseeing 500 Oxford Parkway / Woodstock R7 4 Wood Farm S3 Woodstock 11 Speedwell Street U1 Wheatley 66 Speedwell Street D2 Layover for X32/X39/X40 S1 Speedwell Street D3 35 Abingdon U1 Wheatley X32 Wantage X30 Queems Lane X39/X40 Wallingford 400 Thornhill D4 11 Butterwyke Place R8 4 Botley / Abingdon 66 Butterwyke Place 11 Witney S1 Butterwyke Place 66 Swindon S5 Butterwyke Place S1 Witney X30 Queens Lane U1 Harcourt Hill CS City Sightseeing X30 Wantage 400 Seacourt New Road/Park End Street (south side) R9 8 Terminates F1 8 Hythe Bridge Street 9 Terminates 9 Hythe Bridge Street X32 Terminates S5 Bicester X39/X40 Terminates X32 Hythe Bridge Street R10 1 Rail Station X39/X40 Hythe Bridge Street 5 Rail Station F2 future growth 14 Rail Station F3 future growth 17 Rail Station F4 4 Botley / Abingdon 35 Rail Station 11 Witney 280 Rail Station 66 Swindon 500 Rail Station 400 Seacourt S3 Rail Station S1 Witney X8 Rail Station U1 Harcourt Hill X30 Wantage Stop Route Direction Stop Route Direction Castle Street/Norfolk Street (west side) Castle Street/Norfolk Street (east side) E1 4 Botley -

Council Letter Template

Agenda Item 5 West Area Planning Committee 13th June 2017 Application Number: 17/00250/FUL Decision Due by: 24th May 2017 Proposal: Alterations for the continued use of the buildings as student accommodation comprising: External alterations to elevations and roofs of the existing buildings; tree planting (including containers and supporting structures); alterations to, and landscaping of the courtyards; new cycle stores; alterations to existing lighting; and the formation of pedestrian pathways on the east side of Blocks 5 and 8 and the three gatehouses. Site Address: Castle Mill, Roger Dudman Way (site plan: appendix 1) Ward: Jericho And Osney Ward Agent: Mr Nik Lyzba Applicant: Chancellor, Masters And Scholars Of The University Of Oxford Recommendation: The West Area Planning Committee are recommended to grant planning permission for the following reasons Reasons for Approval 1 It is considered that the proposed design mitigation strategy for the existing buildings will, on balance, provide some mitigation for the harm that has been caused to the significance, in particular to the settings of a number of high value heritage assets. The Environmental Statement has assessed the strategy in respect of the landscape and visual impacts, historic environmental impacts, and impacts on ecology and nature conservation and considers that there will be some beneficial effects from the measures on these matters. Similarly it is not considered to give rise to any impacts with respect to highway matters, land contamination, air quality, and archaeology and any such matters could be addressed by appropriately worded planning conditions. The proposal is considered to be acceptable in terms of the aims and objectives of the National Planning Policy Framework, and relevant policies of the Oxford Core Strategy 2026, Sites and Housing Plan 2011-2026, and Oxford Local Plan 2001-2016 REPORT 13 2 In considering the application, officers have had specific regard to the comments of third parties and statutory bodies in relation to the application. -

Rare Oxford D1 Educational Lease Available

RARE OXFORD D1 EDUCATIONAL LEASE AVAILABLE TRAJAN HOUSE, MILL STREET, OXFORD OX2 0DJ Summary Rare Oxford D1 educational lease available on an assignment or sub- lease basis Three storey, modern building with raised floors, suspended ceilings and part air conditioning Building is currently used as an educational facility Unexpired lease term of c.10 years Central Oxford location within close proximity to the city centre and the mainline railway station, providing direct access to both London Paddington and London Marylebone Car parking for 32 cars including 1 disabled bay Total annual rent of £612,908 pa exclusive, subject to contract and exclusive of VAT 2 Birmingham A40 M1 A40 A509 A1 Cambridge A34 A4144 Northampton M40 B4495 M1 Bedford A5 A428 A34 OXFORD A40 Milton M11 Keynes A1(M) B4150 A421 Luton Oxford A420 A5 A420 A40 St Albans MILL ST OXFORD . M40 A4158 A423 M25 M25 A34 A34 Reading Heathrow M4 A4142 M4 LONDON Not to scale. For indicative purposes only. Location Situation The historic city of Oxford is an affluent centre in the south east, the X90 Oxford-London service and the Oxford Tube (which Trajan House is situated on Mill Street, home to the world-renowned University of Oxford. Oxford is known provides a 24-hour bus service to London), with a journey time of a 5 minute walk from Oxford station and a as the ‘city of dreaming spires’ after the stunning architecture of approximately 100 minutes. 10-12 minute walk to the west of the city the university buildings. The city is one of the fastest growing in centre.