Spiritual but Not Religious: the Influence of the Current Romantic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Romanticism of Francisco De Goya

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The shadow in the light: The dark romanticism of Francisco de Goya Elizabeth Burns-Dans The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Burns-Dans, E. (2018). The shadow in the light: The dark romanticism of Francisco de Goya (Master of Philosophy (School of Arts and Sciences)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/214 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i DECLARATION I declare that this Research Project is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which had not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Elizabeth Burns-Dans 25 June 2018 This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence. i ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the enduring support of those around me. Foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Deborah Gare for her continuous, invaluable and guiding support. -

Abandoned Streets and Past Ruins of the Future in the Glossy Punk Magazine

This is a repository copy of Digging up the dead cities: abandoned streets and past ruins of the future in the glossy punk magazine. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/119650/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Trowell, I.M. orcid.org/0000-0001-6039-7765 (2017) Digging up the dead cities: abandoned streets and past ruins of the future in the glossy punk magazine. Punk and Post Punk, 6 (1). pp. 21-40. ISSN 2044-1983 https://doi.org/10.1386/punk.6.1.21_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Digging up the Dead Cities: Abandoned Streets and Past Ruins of the Future in the Glossy Punk Magazine Abstract - This article excavates, examines and celebrates P N Dead! (a single issue printed in 1981), Punk! Lives (11 issues printed between 1982 and 1983) and Noise! (16 issues in 1982) as a small corpus of overlooked dedicated punk literature coincident with the UK82 incarnation of punk - that takes the form of a pop-style poster magazine. -

I Dress Therefore I Am

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Horton, Kathleen (2005) I dress therefore I am. In Sites of Cosmpolitanism, 2005-07-06 - 2005-07-08. (Unpublished) This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/60755/ c Copyright 2005 All Authors This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. This paper focuses on post-punk London street and club fashion of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Using the rather blunt thematic of the dichotomy between the authentic and the fake, part one of the paper examines some of the tensions that arose when hard-edged punk style was supplanted by the camp extravagances of New Romanticism. -

Partridge, Gothic, Death, Music

Temenos Lecture, 2015 Death, the Gothic, and Popular Music: Some Reflections on Why Popular Music Matters CHRISTOPHER PARTRIDGE Lancaster University, UK. In my recent book, Music and Mortality (2015), I began with the following quotation from a memento mori plaque in Ely Cathedral, England. They are the words of a dead person, a skeleton, addressing visitors to the cathedral: All you that do this place pass bye, Remember death for you will dye. As you are now even so was I, And as I am so shall you be. I pointed out that in previous centuries memento mori exhortations, while popular, were hardly necessary. One’s mortality was all too obvious. However, things are rather different in modern Western societies. Modernity has made the Grim Reaper persona non grata. Death and decay are sequestered in hospitals, hospices, mortuaries and cemeteries, and much cultural energy is expended developing strategies to obscure and to sanitize the brutal facts of mortality. But still, we are, of course, haunted by the inevitability of death. How could we not be? I Researching the issues discussed in Music and Mortality (2015), some of which I am going to address in this lecture, has led to me thinking quite differently about my life, about my family, and about my work—about what matters and also about what really doesn’t matter. Certainly, as I get older and as I reflect on the fact that most of my life is behind me and less than I like to think is probably in front of me certain things come into focus and others drop out of focus. -

Synthpop: Into the Digital Age Morrow, C (1999) Stir It Up: Reggae Album Cover Art

118 POPULAR MUSIC GENRES: AN INTRODUCTION Hebdige, D. (1987) Cut 'n' mix: Identity and Caribbean MUSIc. Comedia. CHAPTER 7 S. (1988) Black Culture, White Youth: The Reggae Tradition/romJA to UK. London: Macmillan. Synthpop: into the digital age Morrow, C (1999) StIr It Up: Reggae Album Cover Art. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. Potash, C (1997) Reggae, Rastafarians, Revolution: Jamaican Musicfrom Ska to Dub. London: Music Sales Limited. Stolzoff, N. C (2000) Wake the Town and Tell the People: Dancehall Culture in Jamaica. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press. Recommended listening Antecedents An overview of the genre Various (1989) The Liquidators: Join The Ska Train. In this chapter, we are adopting the term synthpop to deal with an era Various (1998) Trojan Rocksteady Box Set. Trojan. (around 1979-84) and style of music known by several other names. A more widely employed term in pop historiography has been 'New Generic texts Romantic', but this is too narrowly focused on clothing and fashion, Big Youth ( BurI).ing Spear ( and was, as is ever the case, disowned by almost all those supposedly part Alton (1993) Cry Tough. Heartbeat. of the musical 'movement'. The term New Romantic is more usefully King Skitt (1996) Reggae FIre Beat. Jamaican Gold. employed to describe the club scene, subculture and fashion associated K wesi Johnson, Linton (1998) Linton Kwesi Johnson Independam Intavenshan: with certain elements ofearly 1980s' music in Britain. Other terms used to The Island Anthology. Island. describe this genre included 'futurist' and 'peacock punk' (see Rimmer Bob Marley and The Wailers (1972) Catch A Fire. -

A Critical Evaluation of the Pioneer American Romantic Painter Albert Pinkham Ryder

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2003 Alone with everybody| A critical evaluation of the pioneer American Romantic painter Albert Pinkham Ryder William Bliss The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bliss, William, "Alone with everybody| A critical evaluation of the pioneer American Romantic painter Albert Pinkham Ryder" (2003). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1502. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1502 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen aud Mike MANSFIELD I IBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission __ No, I do not grant permission _ Author's Signature: ^ Date : Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 ALONE WITH EVERYBODY: A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE PIONEER AMERICAN ROMANTIC FAINTER ALBERT PINKHAM RYDER By William Bliss B.A., University of the Pacific Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 2003 Approved by: Chairman, M.A. -

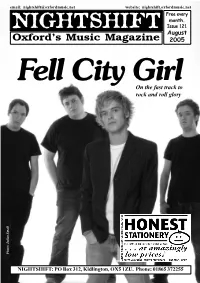

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 121 August Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 Fell City Girl On the fast track to rock and roll glory Photo: Julian Small NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] This month’s issue is dedicated to Albini the Nightshift cat SUPERGRASS play an intimate Ian Parker Band, Michael Myers, show at the Oxford Playhouse this The Invisible and Blue Wax. Music month (Saturday 13th August) as part starts at 7pm. On the Saturday, of a short national tour. The tour is Sunday and Monday, proceedings aimed at promoting new album, kick off at 2pm, with a broad ‘The Road To Rouen’, which marks selection of rock, folk, jazz, blues a change of musical direction for the and acoustic acts, including Leburn, AUGUST band. Kohoutek, Anton Barbeau, Uniting Talking about the tour, singer Gaz the Elements, Sarah Wilson, Laima Every Monday: Coombes said, “It’s gonna be Bite, The Cheesegraters, Tounsi and interesting using these little theatres The Powders. A cheap and extremely THE FAMOUS MONDAY NIGHT BLUES and clubs to show people another cheerful alternative to Reading The best in UK, European and US blues. 8-12. £6 musical side of the band. It’s not Festival. Call 01865 776431 for st something we’ve really done before more details. 1 DIANA BRAITHWAITE (USA) in this way, so we’re excited about it. 8th SHARRIE WILLIAMS & THE WISE We’ll have an old friend playing GOOD AND BAD NEWS for folks GUYS (USA) percussion alongside Danny and his music fans in Oxford this month. -

Cyberpunk Mark Bould

14 Cyberpunk Mark Bould Reflections on “Cyberpunk” The word “Cyberpunk” was coined by Bruce Bethke for the title of a story published in Amazing in 1983, but it came to prominence when Gardner Dozois appropriated it in his 1984 Washington Post article “SF in the Eighties” to describe fiction by William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, Lewis Shiner, Pat Cadigan, and Greg Bear. The self- identified core Cyberpunk group consisted of Gibson, Sterling, Shiner, John Shirley, and Rudy Rucker. They were also dubbed the Movement, the “mirrorshades group” and the “outlaw technologists”; their fiction was sometimes called radical hard SF. As “Cyberpunk” circulated more widely following the success of Gibson’s debut novel Neuromancer (1984), it accreted fresh meanings and applications. To paraphrase Gibson’s famous dictum about human relationships with technology, the street (and the culture industries) found its own uses for “Cyberpunk.” It became an ever-expand- ing term for any slightly edgy artistic or cultural practice concerned with computers and/or the relationships between technology and the body, a synonym for “computer hacker,” the name of a role-playing game and even the title of a Billy Idol album. Although usually considered to refer to a movement, subgenre or an idiom, “Cyber- punk” was also an undeniably commercial label, attracting a lot of attention from readers, writers, journalists, critics, and marketing people. It spawned numerous derivative terms, including “cowpunk,” which described a revitalized western fiction (and had already been applied to the music of the Meat Puppets, whose name Gibson borrowed to describe prostitutes with neural blocks); “elfpunk,” which described post- Tolkien fantasy with attitude; and “ciderpunk,” a variety of pub rock from England’s West Country. -

Goth Subculture Sabrina Newman Johnson & Wales University - Providence, [email protected]

Johnson & Wales University ScholarsArchive@JWU Honors Theses - Providence Campus College of Arts & Sciences 4-26-2018 The volutE ion of the Perceptions of the Goth Subculture Sabrina Newman Johnson & Wales University - Providence, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Repository Citation Newman, Sabrina, "The vE olution of the Perceptions of the Goth Subculture" (2018). Honors Theses - Providence Campus. 27. https://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/student_scholarship/27 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ScholarsArchive@JWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses - Providence Campus by an authorized administrator of ScholarsArchive@JWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Evolution of the Perceptions of the Goth Subculture 1 The Evolution of the Perceptions of the Goth Subculture By Sabrina Newman A Thesis Submitted to the Honors Department of Johnson & Wales University School of Engineering and Design May 2018 The Evolution of the Perceptions of the Goth Subculture 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Introduction 3 Chapter 1 – The History of the Music 12 Chapter 2 – Subcultures Within the Subculture 17 Chapter 3 – Impressions of Goth Throughout the Years 24 Chapter 4 – Survey Results 35 Conclusion 37 Appendix A 39 Works Cited 42 The Evolution of the Perceptions of the Goth Subculture 3 Introduction The Gothic subculture has a rich and interesting history, despite being only approximately 40 years old (Gonzalez). From its origin in the late 1970s to today, the subculture has evolved significantly, and with it the perceptions of said culture. -

Ex Machina Is a Comprehensive Core Rulebook for This Intense Role-Playing Genre

Out of the Machine Covering a range from classic cyberpunk to post cyberpunk, Ex Machina is a comprehensive core rulebook for this intense role-playing genre. In addition to an insightful retrospect of the literary and cinematic genre, Ex Machina features four distinct cyberpunk settings by some of most creative minds in the industry: Bruce Baugh, Christian Gossett and Brad Kayl, Michelle Lyons, and Rebecca R. Borgstrom. Ex Machina also details new rules for cyberware, bioware, and cyberspace, written by Tri-Stat guru David L. Pulver. With dozens of occupational and species templates, vehicles, weapons, and character enhancements, you can create your character and be ready to play in minutes. Lavishly illustrated by the talented artists of Udon, Ex Machina is the final word in cyberpunk role-playing. Sample file WRITTEN BY Bruce Baugh, Rebecca Borgstrom, Christian Gossett, Bradley Kayl, Michelle Lyons ADDITIONAL WRITING BY David Pulver, Jesse Scoble LINE DEVELOPING BY Jesse Scoble with David Pulver EDITING BY Michelle Lyons, James Nicoll ADDITIONAL EDITING BY Adam Jury, RK, Matt Keeley, Chris Kindred, Mark C. MacKinnon ART DIRECTION BY SampleJeff Mackintosh file COVER ART BY Christian Gossett INTERIOR ART BY UDON (with Attila Adorjany, Chris Stevens, Dax Gordine, Eric Kim, Eric Vedder, Greg Boychuk, Jim Zubkavich, Noi Sackda, Ramon Perez, and Ryan Odagawa) © 2004 Guardians Of Order, Inc. All Rights Reserved. GUARDIANS OF ORDER, TRI-STAT SYSTEM, and EX MACHINA are trademarks of Guardians Of Order, Inc. Version 1.0 — October 2004 All right reserved under international law. No part of this book may be reproduced in part or in whole, in any form or by any means, without permission from the publisher, except for personal copies of the character sheet, or brief quotes for use in reviews. -

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Pedagogická Fakulta Ústav Cizích Jazyků

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Pedagogická fakulta Ústav cizích jazyků Bakalářská práce Barbora Zajíčková Ročník: 3. Obor: Anglický jazyk se zaměřením na vzdělávání a společenské vědy se zaměřením na vzdělávání The Subculture of New romantics as a Reaction to the Subculture of Punk Olomouc 2021 Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou práci vypracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. V Olomouci 26.4. 2021 …………………………………………… vlastnoruční podpis I would like to thank to Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. for his support, help and valuable comments on my thesis. Table of contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Terminology .................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Culture and subculture .................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 Contra–culture, movement and scene ........................................................................................... 3 2.3 Style............................................................................................................................................... 3 2.4 Identity .......................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Historical and social background ................................................................................................... -

1 Goth Fashion: from Batcave to Darkwave and Beyond by Ryan V. S

© Ryan V. Stewart, 2018–present | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ARTpublika Magazine: Volume V Submission (Ryan V. Stewart) | 1 Goth Fashion: From Batcave to Darkwave and Beyond By Ryan V. Stewart “Goth”: A phrase which, for many of us, conjures up stereotypical images of pitch black-clad and pale figures, of eerily quiet teenagers seemingly dressed for Halloween year-round; and, perhaps for the more historically-inclined among us, a collection of Germanic tribes whose clashes with the Roman Empire represent some of the most crucial turning points in history. Of course, the former—the cliched idea of teens or young adults who take part in a dreary and doom-laden clique, more likely frequenters of rain-drenched cemeteries, or abandoned and cobwebbed Victorian manors, than varsity athletes or high-rolling yuppies—does have some merit to it: They say that stereotypes are based on at least a kernel of truth, after all. But as much as “goth” is a recognizable term throughout most of the Western world—where counterculture has been, and continues to be, a visible aspect of our societies—it’s also one which, as we near the 2020s, is fairly dated: Though rooted in the late © Ryan V. Stewart, 2018–present | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 ARTpublika Magazine: Volume V Submission (Ryan V. Stewart) | 2 70s British punk scene, especially the post-punk movement and the overarching art punk tendency, and taking influence from glam, and, to a lesser extent, New Wave, goth as a distinguishable, musically-oriented subculture really emerged in the 1980s, and its linchpin genre, gothic rock, flourished throughout that decade, quickly expanding to America and then to other countries.