Handbook of Social Media Management Value Chain and Business Models in Changing Media Markets Media Business and Innovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1616580050.Pdf

СОДЕРЖАНИЕ СОДЕРЖАНИЕ СОДЕРЖАНИЕ 2 ВВЕДЕНИЕ 3 СОЦИАЛЬНЫЕ МЕДИА НА ВЫБОРАХ: НАЧАЛО ДЛИННОГО ПУТИ 4 Становление политических интернет-технологий 1996–2016 4 2016: интернет побеждает телевизор. Феномен Дональда Трампа 5 ПОЛОЖЕНИЕ СОЦИАЛЬНЫХ МЕДИА К СТАРТУ КАМПАНИИ-2020 8 ИСПОЛЬЗОВАНИЕ НОВЫХ ИНСТРУМЕНТОВ В ХОДЕ ПРЕЗИДЕНТСКОЙ ГОНКИ 10 Цифровая стратегия демократов на выборах-2020. «Барометр» 10 Цифровая стратегия Трампа на выборах-2020. Роботизация таргетинга 14 Полевая работа в условиях эпидемии 18 Растущая популярность мобильных приложений 19 Фандрайзинг 22 Предвыборный дискурс и цензура 25 TikTok. Фактор новых соцмедиа в политической агитации 27 КЛЮЧЕВЫЕ ВЫВОДЫ 31 СПИСОК ИСТОЧНИКОВ 32 2 ВВЕДЕНИЕ ВВЕДЕНИЕ Выборы 2020 года в США прошли в самых не- В этом докладе не ставится цель проследить обычных условиях из всех возможных – на фоне хронологию президентской гонки в США и не вы- глобальной пандемии, самого тяжёлого экономи- сказываются оценочные суждения о результатах ческого кризиса за более чем 80 лет и наиболее прошедших выборов. Он посвящён анализу того массовых уличных протестов за последние 50 лет. инструментария, что использовался в ходе пред- Политтехнологам приходится на ходу подстра- выборной борьбы. иваться под эти неожиданные обстоятельства, В самом ближайшем будущем эти технологии адаптируясь к новой реальности. Уже давно про- станут активно использоваться во всём мире. Сле- должающаяся цифровизация современной поли- дует внимательно изучить цифровые тренды в тики лишь ускорилась. планировании и проведении предвыборных кам- На фоне кризиса традиционных медиа и соцсе- паний, агитации, полевой работы и уличной ак- тей появляются альтернативные площадки, на- тивности, которые на деле показали себя в США. бирающие стремительную популярность. Пред- выборная активность уходит в онлайн, где проще и дешевле проводить виртуальные митинги, со- брания сторонников и заниматься мобилизацией избирателей. -

Obama and the Power of Social Media and Technology

The European Business Review Obama and the power of social media and technology This case was prepared by Victoria Chang under the supervision mobile and SMS subscribers. On Election Day alone, supporters received three texts of Professor Jennifer Aaker as the basis for class discussion rather (Exhibit 2).4 than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an The campaign’s social network, www. my.barackobama.com (MyBO), allowed indi- administrative situation. Contributors included Joe Rospars, viduals to connect to one another and acti- vate themselves on behalf of the campaign. Chris Hughes, Sam Graham-Felsen, Kate Albright-Hanna, Scott Two million profiles were created. Registered Goodstein, Steve Grove, Randi Zuckerberg, Chloe Sladden and users and volunteers planned over 200,000 offline events, wrote 400,000 blog posts, and Brittany Bohnet. created 35,000 volunteer groups. Obama raised $639 million from 3 million donors, mostly through the Internet.5 Volunteers n early 2007, Barack Obama was a ers on Twitter, more than 23 times those of on MyBO generated $30 million on 70,000 little-known senator running for presi- McCain. Fifty million viewers spent 14 million personal fundraising pages.6 Donors made dent against Democratic nominee and hours watching campaign-related videos on 6.5 million donations online, totaling more Ihousehold name, Hilary Clinton. But on No- YouTube, four times McCain’s viewers.3 The than $500 million. Of those donations, 6 vember 4, 2008, Obama, 47, was the first Afri- campaign sent out 1 billion e-mails, includ- million were in increments of $100 or less, can American to win the election against Re- ing 10,000 unique messages targeted at spe- the average being $80. -

Applications Log Viewer

4/1/2017 Sophos Applications Log Viewer MONITOR & ANALYZE Control Center Application List Application Filter Traffic Shaping Default Current Activities Reports Diagnostics Name * Mike App Filter PROTECT Description Based on Block filter avoidance apps Firewall Intrusion Prevention Web Enable Micro App Discovery Applications Wireless Email Web Server Advanced Threat CONFIGURE Application Application Filter Criteria Schedule Action VPN Network Category = Infrastructure, Netw... Routing Risk = 1-Very Low, 2- FTPS-Data, FTP-DataTransfer, FTP-Control, FTP Delete Request, FTP Upload Request, FTP Base, Low, 4... All the Allow Authentication FTPS, FTP Download Request Characteristics = Prone Time to misuse, Tra... System Services Technology = Client Server, Netwo... SYSTEM Profiles Category = File Transfer, Hosts and Services Confe... Risk = 3-Medium Administration All the TeamViewer Conferencing, TeamViewer FileTransfer Characteristics = Time Allow Excessive Bandwidth,... Backup & Firmware Technology = Client Server Certificates Save Cancel https://192.168.110.3:4444/webconsole/webpages/index.jsp#71826 1/4 4/1/2017 Sophos Application Application Filter Criteria Schedule Action Applications Log Viewer Facebook Applications, Docstoc Website, Facebook Plugin, MySpace Website, MySpace.cn Website, Twitter Website, Facebook Website, Bebo Website, Classmates Website, LinkedIN Compose Webmail, Digg Web Login, Flickr Website, Flickr Web Upload, Friendfeed Web Login, MONITOR & ANALYZE Hootsuite Web Login, Friendster Web Login, Hi5 Website, Facebook Video -

2019 Winners & Finalists

2019 WINNERS & FINALISTS Associated Craft Award Winner Alison Watt The Radio Bureau Finalists MediaWorks Trade Marketing Team MediaWorks MediaWorks Radio Integration Team MediaWorks Best Community Campaign Winner Dena Roberts, Dominic Harvey, Tom McKenzie, Bex Dewhurst, Ryan Rathbone, Lucy 5 Marathons in 5 Days The Edge Network Carthew, Lucy Hills, Clinton Randell, Megan Annear, Ricky Bannister Finalists Leanne Hutchinson, Jason Gunn, Jay-Jay Feeney, Todd Fisher, Matt Anderson, Shae Jingle Bail More FM Network Osborne, Abby Quinn, Mel Low, Talia Purser Petition for Pride Mel Toomey, Casey Sullivan, Daniel Mac The Edge Wellington Best Content Best Content Director Winner Ryan Rathbone The Edge Network Finalists Ross Flahive ZM Network Christian Boston More FM Network Best Creative Feature Winner Whostalk ZB Phil Guyan, Josh Couch, Grace Bucknell, Phil Yule, Mike Hosking, Daryl Habraken Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Finalists Tarore John Cowan, Josh Couch, Rangi Kipa, Phil Yule Newstalk ZB Network / CBA Poo Towns of New Zealand Jeremy Pickford, Duncan Heyde, Thane Kirby, Jack Honeybone, Roisin Kelly The Rock Network Best Podcast Winner Gone Fishing Adam Dudding, Amy Maas, Tim Watkin, Justin Gregory, Rangi Powick, Jason Dorday RNZ National / Stuff Finalists Black Sheep William Ray, Tim Watkin RNZ National BANG! Melody Thomas, Tim Watkin RNZ National Best Show Producer - Music Show Winner Jeremy Pickford The Rock Drive with Thane & Dunc The Rock Network Finalists Alexandra Mullin The Edge Breakfast with Dom, Meg & Randell The Edge Network Ryan -

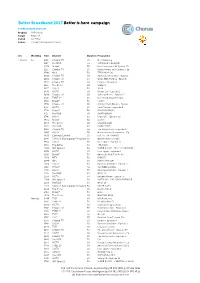

BB2017 Media Overview for Rsps

Better Broadband 2017 Better is here campaign TV PRE AIRDATE SPOTLIST Product All Products Target All 25-54 Period wc 7 May Source TVmap/The Nielsen Company w/c WeekDay Time Channel Duration Programme 7 May 17 Su 1112 Choice TV 30 No Advertising 7 May 17 Su 1217 the BOX 60 SURVIVOR: CAGAYAN 7 May 17 Su 1220 Bravo* 30 Real Housewives Of Sydney, Th 7 May 17 Su 1225 Choice TV 30 Better Homes and Gardens - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1340 MTV 30 TEEN MOM OG 7 May 17 Su 1410 Choice TV 30 American Restoration - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1454 Choice TV 60 Walks With My Dog - Episode 7 May 17 Su 1542 Choice TV 60 Empire - Episode 4 7 May 17 Su 1615 The Zone 60 SLIDERS 7 May 17 Su 1617 HGTV 30 16:00 7 May 17 Su 1640 HGTV 60 Hawaii Life - Episode 2 7 May 17 Su 1650 Choice TV 60 Jamie at Home - Episode 5 7 May 17 Su 1710 TVNZ 2* 60 Home and Away Omnibus 7 May 17 Su 1710 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1710 Choice TV 30 Jimmy's Farm Diaries - Episod 7 May 17 Su 1717 HGTV 30 Yard Crashers - Episode 8 7 May 17 Su 1720 Prime* 30 RUGBY NATION 7 May 17 Su 1727 the BOX 30 SMACKDOWN 7 May 17 Su 1746 HGTV 60 Island Life - Episode 10 7 May 17 Su 1820 Bravo* 30 Catfish 7 May 17 Su 1854 The Zone 60 WIZARD WARS 7 May 17 Su 1905 the BOX 30 MAIN EVENT 7 May 17 Su 1906 Choice TV 60 The Living Room - Episode 37 7 May 17 Su 1906 HGTV 30 House Hunters Renovation - Ep 7 May 17 Su 1930 Comedy Central 30 LIVE AT THE APOLLO 7 May 17 Su 1945 Crime & Investigation Network 30 DEATH ROW STORIES 7 May 17 Su 1954 HGTV 30 Fixer Upper - Episode 6 7 May 17 Su 1955 The Zone 60 THE CAPE 7 May 17 Su 2000 -

Instagram and an Indonesian Ideal Leader

Proceedings of SOCIOINT 2019- 6th International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities 24-26 June 2019- Istanbul, Turkey INSTAGRAM AND AN INDONESIAN IDEAL LEADER Wahyu Eka Putri1, Eriyanto2* 1S.KPm., Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Indonesia, Indonesia, [email protected] 2Dr.,M.Si, Department of Communication Science, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, University of Indonesia, Indonesia, [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract This article explores Indonesian elected president activities on Instagram during the 2019 election. Instagram create new ways to market political campaigns through the displayed images and new channels for candidates and voters to interact. Self-framing displayed enable to present identifiable image for candidates. To explore the role that images play in framing political character and to identify which images received higher levels of engagement, content analyses were performed on candidates’ Instagram account. Political framing identification uses the potential frames character that had previously been carried by Grabe dan Bucy. Grab and Bucy identify images used in the campaign to create a particular political character. The purpose of this study is to describe the representation of Indonesian ideal leader on instagram by using multimodal analysis to understand how Instagram images convey meaning that helps to create those frames. This research concludes with a discussion of the utility of multimodal analysis in understanding campaign images that support the created framing characters. As a candidate, Joko Widodo most frequently employes the ideal candidate frame with subdimensions of statesmanship and compassion. Joko Widodo, as an incumbent candidate, does not show his achievements or symbol of progress as a campaign tool in his image. -

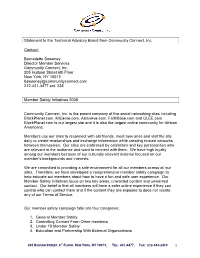

Community Connect Input

Statement to the Technical Advisory Board from Community Connect, Inc. Contact: Bernadette Sweeney Director Member Services Community Connect, Inc. 205 Hudson Street 6th Floor New York, NY 10013 [email protected] 212-431-4477 ext. 238 Member Safety Initiatives 2008 Community Connect, Inc. is the parent company of five social networking sites including BlackPlanet.com, MiGente.com, AsianAve.com, FaithBase.com and GLEE.com. BlackPlanet.com is our largest site and it is also the largest online community for African Americans. Members use our sites to reconnect with old friends, meet new ones and visit the site daily to create relationships and exchange information while creating trusted networks between themselves. Our sites are embraced by celebrities and key personalities who are relevant to the audience and want to connect with them. We have high loyalty among our members because of our culturally relevant material focused on our member’s backgrounds and interests. We are committed to providing a safe environment for all our members across all our sites. Therefore, we have developed a comprehensive member safety campaign to help educate out members about how to have a fun and safe user experience. Our Member Safety initiatives focus on two key areas, unwanted content and unwanted contact. Our belief is that all members will have a safer online experience if they can control who can contact them and if the content they are exposed to does not violate any of our Terms of Service. Our member safety campaign falls into four categories: 1. General Member Safety 2. Controlling Contact From Other members 3. -

The Complete Guide to Social Media from the Social Media Guys

The Complete Guide to Social Media From The Social Media Guys PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 08 Nov 2010 19:01:07 UTC Contents Articles Social media 1 Social web 6 Social media measurement 8 Social media marketing 9 Social media optimization 11 Social network service 12 Digg 24 Facebook 33 LinkedIn 48 MySpace 52 Newsvine 70 Reddit 74 StumbleUpon 80 Twitter 84 YouTube 98 XING 112 References Article Sources and Contributors 115 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 123 Article Licenses License 125 Social media 1 Social media Social media are media for social interaction, using highly accessible and scalable publishing techniques. Social media uses web-based technologies to turn communication into interactive dialogues. Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein define social media as "a group of Internet-based applications that build on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0, which allows the creation and exchange of user-generated content."[1] Businesses also refer to social media as consumer-generated media (CGM). Social media utilization is believed to be a driving force in defining the current time period as the Attention Age. A common thread running through all definitions of social media is a blending of technology and social interaction for the co-creation of value. Distinction from industrial media People gain information, education, news, etc., by electronic media and print media. Social media are distinct from industrial or traditional media, such as newspapers, television, and film. They are relatively inexpensive and accessible to enable anyone (even private individuals) to publish or access information, compared to industrial media, which generally require significant resources to publish information. -

WHERE ARE the EXTRA ANALYSIS September 2020

WHERE ARE THE AUDIENCES? EXTRA ANALYSIS September 2020 Summary of the net daily reach of the main TV broadcasters on air and online in 2020 Daily reach 2020 – net reach of TV broadcasters. All New Zealanders 15+ • Net daily reach of TVNZ: 56% – Includes TVNZ 1, TVNZ 2, DUKE, TVNZ OnDemand • Net daily reach of Mediaworks : 25% – Includes Three, 3NOW • Net daily reach of SKY TV: 22% – Includes all SKY channels and SKY Ondemand Glasshouse Consulting June 20 2 The difference in the time each generation dedicate to different media each day is vast. 60+ year olds spend an average of nearly four hours watching TV and nearly 2½ hours listening to the radio each day. Conversely 15-39 year olds spend nearly 2½ hours watching SVOD, nearly two hours a day watching online video or listening to streamed music and nearly 1½ hours online gaming. Time spent consuming media 2020 – average minutes per day. Three generations of New Zealanders Q: Between (TIME PERIOD) about how long did you do (activity) for? 61 TV Total 143 229 110 Online Video 56 21 46 Radio 70 145 139 SVOD Total 99 32 120 Music Stream 46 12 84 Online Gaming 46 31 30 NZ On Demand 37 15-39s 26 15 40-59s Music 14 11 60+ year olds 10 Online NZ Radio 27 11 16 Note: in this chart average total minutes are based on a ll New Zealanders Podcast 6 and includes those who did not do each activity (i.e. zero minutes). 3 Media are ranked in order of daily reach among all New Zealanders. -

Download 2018 Media Guide

14–18 May 2018 Be heard A media guide for schools TOGETHER WE CAN STOP BULLYING AT OUR SCHOOL www.bullyingfree.nz Contents Why use the media? ................................................................................................... 3 Developing key messages .......................................................................................... 4 News outlets ............................................................................................................... 6 Being in the news ...................................................................................................... 9 Writing a media release ........................................................................................... 10 Tips on media interviews ......................................................................................... 12 Involving students in media activity ........................................................................... 13 Responding to media following an incident .............................................................. 14 Who we are Bullying-Free NZ Week is coordinated by the Bullying Prevention Advisory Group (BPAG). BPAG is an interagency group of 17 organisations, with representatives from the education, health, justice and social sectors, as well as internet safety and human rights advocacy groups. BPAG members share the strongly held view that bullying behaviour of any kind is unacceptable and are committed to ensuring combined action is taken to reduce bullying in New Zealand Schools. Find out more -

Critical Literacy in Support of Critical-Citizenship Education in Social Studies

TEACHING AND LEARNING Critical literacy in support of critical-citizenship education in social studies JANE ABBISS KEY POINTS • Critical-literacy approaches support justice-oriented, critical-citizenship education in social studies. • Developing learner criticality involves analysis of texts, including exploration of author viewpoints, assumptions made, matters of inclusion, and learner responses to social issues and how they are represented in texts. • Taking a critical literacy approach to support critical citizenship involves re-thinking how students in social studies engage with media sources. • Critical literacy aids informed decision-making on social issues. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0054 set 3, 2016 29 TEACHING AND LEARNING How might social-studies teachers enact critical forms of citizenship education in classrooms and what pedagogies support this? This question is explored in relation to literature about critical citizenship and critical literacy. Also, possibilities for practice are considered and two approaches for critical literacy in social studies are presented: a) using critical questions to engage with texts; and b) focusing on media literacy in relation to current events. It is argued that critical literacy offers a collection of approaches that support justice-oriented, critical-citizenship education in social studies. Introduction Methodologically, this article presents a literature- based, small-scale practitioner inquiry relating to The aim of this article is twofold: first, to briefly challenges in supporting citizenship teaching and explore some contested views of citizenship education learning in social studies. At its core is a commitment and to consider the aims and foundations of critical to informing practice (Cochrane-Smith & Donnell, literacy as a collection of pedagogical approaches 2006; Smith & Helfenbein, 2009). -

WHERE ARE the AUDIENCES? August 2021 Introduction

WHERE ARE THE AUDIENCES? August 2021 Introduction • New Zealand On Air (NZ On Air) supports and funds public media content for New Zealand audiences, focussing on authentic NZ stories and songs that reflect New Zealand’s cultural identity and help build social cohesion, inclusion and connection. • It is therefore essential NZ On Air has an accurate understanding of the evolving media behaviour of NZ audiences. • The Where Are The Audiences? study delivers an objective measure of NZ audience behaviour at a time when continuous single source audience measurement is still in development. • This document presents the findings of the 2021 study. This is the fifth wave of the study since the benchmark in 2014 and provides not only a snapshot of current audience behaviour but also how behaviour is evolving over time. • NZ On Air aims to hold a mirror up to New Zealand and its people. The 2021 Where Are The Audiences? study will contribute to this goal by: – Informing NZ On Air’s content and platform strategy as well as the assessment of specific content proposals – Positioning NZ On Air as a knowledge leader with stakeholders. – Maintaining NZ On Air’s platform neutral approach to funding and support, and ensuring decisions are based on objective, single source, multi-media audience information. Glasshouse Consulting July 21 2 Potential impact of Covid 19 on the 2020 study • The Where Are The Audiences? study has always been conducted in April and May to ensure results are not influenced by seasonal audience patterns. • However in 2020 the study was delayed to May-June due to levels 3 and 4 Covid 19 lockdown prior to this period.