Tabletop Role-Playing Games, Narrative, and Individual Development Benjamin Luke Flournoy Gardner-Webb University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gilsdorf Press Kit 2014

857 756 9101 | [email protected] | www.ethangilsdorf.com facebook.com/fantasyfreaksbook | twitter ethanfreak For the electronic version of this press kit, plus author photos, book jacket art, and stills from the book, see: http://www.ethangilsdorf.com/pressroom/ "The hardest-working geek we know, Ethan Gilsdorf."—The Boston Phoenix "Boston nerdlord writer Ethan Gilsdorf"—The Quad "Somerville’s resident d20 dorkwad"—The Weekly Dig Author of FANTASY FREAKS AND GAMING GEEKS: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms “Part personal odyssey, part medieval mid-life crisis, and part wide-ranging survey of all things freaky and geeky”— Huffington Post "Lord of the Rings meets Jack Kerouac’s On the Road"— National Public Radio “For anyone who has ever spent time within imaginary realms, the book will speak volumes.” —Wired.com “Gandalf’s got nothing on Ethan Gilsdorf, except for maybe the monster white beard. In his new book, Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks, Gilsdorf . offers an epic quest for reality within a realm of magic.” —Boston Globe Representation Sorche Fairbank, Fairbank Literary Representation, P.O. Box 6, Hudson, New York 12534-0006 (USA); tel: 617.576.0030, [email protected], http://www.fairbankliterary.com About Ethan Gilsdorf: Biography Ethan Gilsdorf is a journalist, memoirist, critic, poet, teacher and 17th level geek. He is the author of the award-winning travel memoir investigation Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms. Based in Somerville, Massachusetts, Gilsdorf writes regularly for the New York Times, Boston Globe, Salon.com, BoingBoing.net, PsychologyToday.com, Washington Post and wired.com. -

Sherry Turkle on the Power of Talking (Face to Face) - the Boston Globe 10/3/15, 7:48 AM

Sherry Turkle on the power of talking (face to face) - The Boston Globe 10/3/15, 7:48 AM Cheese, beer, wine. Saturday at Copley Square. HUBWEEK List of events GlobeDocs festival Live updates Full coverage THE TECH NOMAD Sherry Turkle on the power of talking (face to face) By Ethan Gilsdorf GLOBE CORRESPONDENT OCTOBER 02, 2015 “Who in this cafe is talking?” Sherry Turkle looks around a trendy coffee shop in Downtown Crossing. The walls are lined with old tomes, a thematic decorative touch, but the books aren’t meant to be read. Aside from Turkle and a guest, one other couple is chatting. Most patrons are hunched over laptops and smart phones, working, texting, or watching something on a screen. “So, we’ve got four people talking,” she sighs. “Two groups of two. OK, that’s not JOE TABACCA FOR THE BOSTON GLOBE very good.” http://www.bostonglobe.com/lifestyle/2015/10/02/sherry-turkle-power-talking-face-face/r6RFoy1LZBT4gIk2I0WJoK/story.html Page 1 of 5 Sherry Turkle on the power of talking (face to face) - The Boston Globe 10/3/15, 7:48 AM Turkle, 67, professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a prolific author, wants to have a conversation. About conversation — and why so few people seem interested in having, or are able to have, that face-to-face anymore. The crisis of conversation is at the heart of Turkle’s new book, “Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age.” With it, she hopes to spark a discussion about what we lose when we settle for fleeting texts, sound bites, and status updates, instead of pursuing meaningful, nuanced human connection. -

Boston Book Festival 2014 Announces Complete

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Ami Bennitt 617.797.8267, [email protected] BOSTON BOOK FESTIVAL 2014 ANNOUNCES COMPLETE LINE-UP, SESSION TOPICS, TIMES, AND LOCATIONS FOR SIXTH ANNUAL FESTIVAL, OCTOBER 23-25, 2014 OVER 50 FREE SESSIONS, ACTIVITIES, AND MORE For festival press credentials, interviews, and images, please email. [Boston, MA – October 2, 2014] The Boston Book Festival, in partnership with WBUR 90.9 FM, announces the complete schedule and locations for the widely anticipated annual event, taking place October 23-25 at locations in and around Copley Square. Festival events include presentations and panels featuring the internationally-known writers, scholars, critics, and commentators listed below; programming for children, teens, and families; writing seminars and competitions; outdoor booths; and spoken word and music performances. All daytime events are FREE and open to the public with no reservations required. The festival also features two ticketed events: a Memoir Keynote by Grammy Award-winner, composer, performer, and author Herbie Hancock , Thursday, October 23, 8PM, at Old South Church; and Art, Architecture, and Design Keynote by renowned architect Norman Foster , Saturday, October 25, 4PM, at Trinity Church. Tickets for Herbie Hancock are $15; Norman Foster $10, and may be purchased online at bostonbookfestival.org. LOCATION ADDRESSES Boston Common Hotel, 40 Trinity Place, Boston Church of the Covenant , 67 Newbury Street, Boston Emmanuel Church , 15 Newbury Street, Boston First Church , 66 Marlborough Street, Boston French Cultural Center , 53 Marlborough Street, Boston Old South Church , 645 Boylston Street Storyville , 90 Exeter Street, Boston Trinity Church , 206 Clarendon Street, Boston and outdoors in Copley Square. More information, including complete author biographies, is available at bostonbookfest.org . -

Dungeons & Dragons and Philosophy: Read and Gain Advantage on All Wisdom Checks

DUNGEONS & DRAGONS AND PHILOSOPHY The Blackwell Philosophy and PopCulture Series Series editor William Irwin A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down, and a healthy helping of popular culture clears the cobwebs from Kant. Philosophy has had a public relations problem for a few centuries now. This series aims to change that, showing that philosophy is relevant to your life – and not just for answering the big questions like “To be or not to be?” but for answering the little questions: “To watch or not to watch South Park?” Thinking deeply about TV, movies, and music doesn’t make you a “complete idiot.” In fact it might make you a philosopher, someone who believes the unexamined life is not worth living and the unexamined cartoon is not worth watching. Already published in the series: 24 and Philosophy: The World According to Jack The Hunger Games and Philosophy: A Critique of Pure Edited by Jennifer Hart Weed, Richard Brian Davis, and Treason Ronald Weed Edited by George Dunn and Nicolas Michaud 30 Rock and Philosophy: We Want to Go to There Inception and Philosophy: Because It’s Never Just a Dream Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Edited by David Johnson Alice in Wonderland and Philosophy: Curiouser and Iron Man and Philosophy: Facing the Stark Reality Curiouser Edited by Mark D. White Edited by Richard Brian Davis Lost and Philosophy: The Island Has Its Reasons Arrested Development and Philosophy: They’ve Made a Edited by Sharon M. Kaye Huge Mistake Mad Men and Philosophy: Nothing Is as It Seems Edited by Kristopher Phillips and J. -

2010 Annual Conference & Bookfair Schedule

2010 Annual Conference & Bookfair Schedule April 7‐10, 2010 Denver, Colorado Hyatt Regency Denver & Colorado Convention Center This schedule is a draft and may be modified. Wednesday‐ April 7, 2010 Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Noon‐5:30 p.m. Exhibit Hall A W100. Bookfair Setup. Exhibit Hall A at the Colorado Convention Center will Colorado Convention be open for setup. For safety and security reasons, only those wearing an Center, Upper Level exhibitor access badge or those accompanied by an individual wearing an exhibitor access badge will be permitted inside the bookfair during setup hours. Bookfair exhibitors are welcome to pick up their registration materials in the Paid Registrant Check‐In area located just inside the main entrance to the bookfair on the upper level. Noon‐7:00 p.m. Exhibit Hall A W101. Conference Registration. Attendees who have registered in advance Colorado Convention may pick up their registration materials throughout the day at AWP's Paid Center, Upper Level Registrant Check‐In, located just inside the main entrance to the bookfair. Badges are available for purchase at the Unpaid Registrant Check‐In located on the street level of the Convention Center. 4:30 p.m.‐5:45 p.m. Granite W102. WITS Membership Meeting. (Robin Reagler) Writers in the Schools Hyatt Regency (WITS) Alliance invites current and prospective members to attend a general Denver, 3rd Floor meeting lead by Robin Reagler, Executive Director of WITS‐Houston. 5:00 p.m.‐6:30 p.m. Mineral Hall W103. CLMP & SPD Publisher Meeting. (Tasha Sorenson) The staffs of the Hyatt Regency Council of Literary Magazines and Presses and Small Press Distribution discuss Denver, 3rd Floor issues facing CLMP and SPD publishers, goals for the organizations, and upcoming programs. -

FANTASY FREAKS and GAMING GEEKS an Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms

Speak, Friend, and Enter... author Ethan Gilsdorf presents FANTASY FREAKS AND GAMING GEEKS An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms Hosted by St. Mark's Bookshop (31 Third Avenue, 212-260-7853, www.stmarksbookshop.com) Solas Bar, 232 East 9th Street (between 2nd & 3rd Avenues), New York City Thursday, October 8 at 7:30pm “A breathless adventure quest / memoir that is uniquely contemporary.” —Andrei Codrescu, NPR commentator “For anyone who has ever spent time within imaginary realms, the book will speak volumes. For those who have not, it will educate and enlighten." —Wired.com A "Geek Trivia Contest" with prizes will test your knowledge of all things Tolkien, Harry Potter, Dungeons & Dragons and more! COME COMMUNE WITH YOUR INNER FANTASY FAN OR GAMING GEEK! MORE INFO AND U.S. TOUR DATES: www.fantasyfreaksbook.com **For more information, or to schedule an interview with Ethan Gilsdorf, author of Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks, contact: Bob Sembiante, Publicist, Globe Pequot Press [email protected] 203-458-4555 High resolution author images, book jacket art, press kit and more downloadable at http://www.ethangilsdorf.com/pressroom/ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Author Ethan Gilsdorf brings Fantasy Freaks and Gaming Geeks to St Mark’s Bookshop/Solas Bar, Thurs, October 8 Come commune with your inner fantasy fan or gaming geek with Ethan Gilsdorf, author of the travel memoir / pop culture narrative FANTASY FREAKS AND GAMING GEEKS: An Epic Quest for Reality Among Role Players, Online Gamers, and Other Dwellers of Imaginary Realms. Gilsdorf reads from the book Thursday, October 8 at 7:30pm at Solas Bar, 232 East 9th Street (between 2nd and 3rd Avenues), New York, NY. -

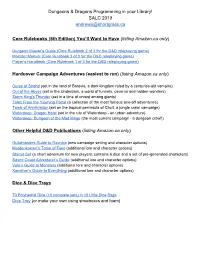

Dungeons & Dragons Programming in Your Library! SALC 2019 Andrewp

Dungeons & Dragons Programming in your Library! SALC 2019 [email protected] Core Rulebooks (5th Edition) You’ll Want to Have (listing Amazon.ca only) Dungeon Master’s Guide (Core Rulebook 2 of 3 for the D&D roleplaying game) Monster Manual (Core Rulebook 3 of 3 for the D&D roleplaying game) Player’s Handbook (Core Rulebook 1 of 3 for the D&D roleplaying game) Hardcover Campaign Adventures (easiest to run) (listing Amazon.ca only) Curse of Strahd (set in the land of Barovia, a dark kingdom ruled by a centuries-old vampire) Out of the Abyss (set in the Underdark, a world of tunnels, caverns and hidden wonders) Storm King’s Thunder (set in a time of unrest among giants) Tales From the Yawning Portal (a collection of the most famous one-off adventures) Tomb of Annihilation (set on the tropical peninsula of Chult, a jungle crawl campaign) Waterdeep: Dragon Heist (set in the city of Waterdeep - an urban adventure) Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage (the most current campaign - a dungeon crawl!) Other Helpful D&D Publications (listing Amazon.ca only) Guildmasters Guide to Ravnica (new campaign setting and character options) Mordenkainen’s Tome of Foes (additional lore and character options) Starter Set (a short adventure for new players; contains 6 dice and a set of pre-generated characters) Sword Coast Adventurer’s Guide (additional lore and character options) Volo’s Guide to Monsters (additional lore and character options) Xanathar’s Guide to Everything (additional lore and character options) -

67 Books Every Geek Should Read to Their Kids Before Age 10."

The GeekDad community at Wired.com is committed to helping you raise geek generation 2.0. We believe few things that you do are more important than reading to your kids early and often. Reading to them is a great way to get them using the language centers of their brain. Plus, reading aloud to your kids can be a blast. In March of 2012 we put out a post of our favorite books to read aloud to our kids before the age of ten. Well, the post turned out to be a bit of a crowd-pleaser. Many educators and parents asked us to put together a printed version of "67 Books Every Geek Should Read to Their Kids Before Age 10." While we never intended this to be a comprehensive list of what you should read to your kids, we certainly missed some obvious choices. After we published our list, we received a huge number of wonderful suggestions from readers. Their suggestions were placed into a second post, "Books Geeks Should Read to Their Kids: Your Additions to Our List." They are also included here. Enjoy and happy Reading! 67 Books Every Geek Should Read to Their Kids Before Age 10 Recommended by Erik Wecks, Matt Blum, Kevin Makice, Nathan Berry, Jonathan Liu, Dave Banks, Roy Wood, Kathy Ceceri, Jenny Williams, Ethan Gilsdorf, Corrina Lawson, Michael Venables, and GeekDad Z: Brian Selznick, The Invention of Hugo Cabret Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows Kate DiCamillo, The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane Barbara Park, Junie B. Jones's First Boxed Set Ever! (Books 1-4) Shel Silverstein, Where the Sidewalk Ends, A Light in the Attic, Falling Up, and Every Thing on It J. -

Icon Gilsdorf

101000010011001100011011 Icon 101101001000100100100100 .com/cobalt 111001010101001000111100 If placelessness finally reigns, it’s not me, the ‘merican, haunting this apartment, 000100100101001000100111 but my shortcut on the French-language 001010100110101011100011 operating system’s desktop. My latest release. 011100000011010110101110 My icon I click and drag behind me, 001010101101011110011011 August 31, 2004 ~ PoetrySuperHighway a mini and memorable identity, my logo. My little DNA-infused flag to wave 11000001100100000000000 at the parade of interface. 000000000011010101010101 My folder’s full of docs. And near-copies 111100110010010110101001 Cobalt Poets Series # 50 ~ of who I am exist invisibly on the chip. 011101010000100110011000 Just like in “the future.” 1101110110100100010010010 I have to keep persuading the spellchecker 0100111001010101001000111 it’s English (US), not French (France), puh-leeze. I guard both passport and passwords. 100000100100101001000100 I had saved a country once to disk. It’s here somewhere. 1110010101001101010111000 All night, the baby hard drive purrs and coos 1101110000001101011010111 from the other room. Satisfied, we sleep. 0001010101101011110011011 The DSL umbilicus branches into the data fields, searching for homesickness’s salve and remedy. 110000011001000000000000 000000000110101010101011 All night, behind our slumber, Ethan tirelessly trolling the pixel-dark seas. 1110011001001011010100101 110101000010011001100011 011101101001000100100100Gilsdorf 1001110010101010010001111 000001001001010010001001 -

The Birth of Fantasy Role-Playing Games

chapter 1 The Birth of Fantasy Role-Playing Games Imagination is but another name for super intelligence. —Edgar Rice Burroughs, Jungle Tales of Tarzan All men dream: but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to fi nd that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dream with open eyes, to make it possible. —T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom Dungeons & Dragons inspired countless other fantasy role-playing games, defi ning the genre.1 The origins of Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson’s extremely successful game did not lie in theater or storytelling but in wargaming—a hobby in which players simulate historical battles using miniature soldiers. Wargaming developed in the nineteenth cen- tury, primarily as a training exercise for Prussian military offi cers. It was eventually adapted for civilian leisure, but it has remained an obscure hobby. Not only does wargaming demand a serious interest in military history, but the rules frequently require complex mathematical calculations and charts that most people would regard as a tedious exercise rather than entertainment. Thus wargaming was an unlikely midwife for the genre of fantasy role-playing. D&D combined two very diff erent ways of thinking about the world. On the one hand, it entailed a preoccupation with mathematical models and rules, the roots of which can be traced back to Prussian offi cers per- fecting “the science of war.” On the other hand, it refl ected the cultural trends of the 1960s, including a fascination with history, myth, and 31 32 | The History of the Panic fantasy as well as a renewed appreciation for values such as cooperation and imagination. -

Gygax Magazine Issue 1

CONTENTS Issue #1 FEATURES Volume I, No. 1 9 The cosmology of role-playing games - James Carpio illustrated by Alyssa Faden February 2013 Everything is interconnected – but how is it all related? 14 Still playing after all these years - Tim Kask illustrated by Barrie James Publishers What Tim’s really keeping behind that DM’s screen Editor-in-chief Jayson Elliot 16 Leomund’s Secure Shelter - Lenard Lakofka Jayson Elliot Ernest Gary Gygax Jr. AD&D, math, and magic items. What’s better, +1 to damage or to hit? Luke Gygax Editors 18 The ecology of the banshee - Ronald Corn illustrated by Michał Kwiatkowski Mary Lindholm Contributing editor If you hear her wail, it’s already too late Hanae Ko Tim Kask 22 Bridging generations - Luke Gygax Stories fathers tell . and rediscover Community Manager Art director 23 Gaming with a virtual tabletop - Nevin P. Jones Susan Silver Jim Wampler Playing face to face when you can’t be in the same place Contributing writers Games editor 24 Keeping magic magical - Dennis Sustare illustrated by Simon Adams Rodrigo Garcia Carmona James Carpio Liven up the magic in your game, whatever system you play James Carpio 26 Playing it the science fiction way - James M. Ward illustrated by Barrie James Ronald Corn Kobold editor Disrupt your fantasy campaign with an unexpected twist Michael Curtis Wolfgang Baur 28 DMing for your toddler - Cory Doctorow illustrated by Hanae Ko Dennis Detwiller A four-year-old’s first d20 Cory Doctorow Contributing artists Ethan Gilsdorf Simon Adams 30 Great power for ICONS - Steve Kenson illustrated by Jeff Dee Ernest Gary Gygax Jr. -

E-Sports and the World of Competitive Gaming

THE WORLD OF THE WORLD OF VIDEO GAMES THE WORLD OF VIDEO The World of Video Games VIDEO GAMES explores the many topics and GAMES controversies in the video game industry. Readers will learn about such topics as the E-SPORTS AND history of video games, breakthrough technologies, and the rising popularity of E-Sports. They will understand how AND OFE-SPORTS THE WORLD THE WORLD OF video games affect both individual people and society. The books look ahead to the future, charting the likely future paths of the video game industry. Each volume includes diagrams to enhance COMPETITIVE readers’ understanding of complex concepts, source notes, and an annotated bibliography to facilitate deeper research. GAMING COMPETITIVE GAMING By Heather L. Bode TITLES IN THE SERIES INCLUDE: VIDEO GAME ADDICTION E-SPORTS AND THE WORLD OF VIDEO GAMES AND COMPETITIVE GAMING CULTURE Press ReferencePoint VIOLENCE GAMING AND VIDEO GAMES TECHNOLOGY: BLURRING REAL AND YOUTH VIRTUAL WORLDS AND VIDEO GAMES CONTENTS IMPORTANT EVENTS IN THE HISTORY OF VIDEO GAMES 4 INTRODUCTION 6 Gaming as a Job CHAPTER 1 10 The History of Competitive Gaming CHAPTER 2 24 How Do People Play E-Sports? CHAPTER 3 40 How Do E-Sports Affect Society? CHAPTER 4 56 The Future of E-Sports and Competitive Gaming Source Notes 70 For Further Research 74 Index 76 Image Credits 79 About the Author 80 IMPORTANT EVENTS IN THE HISTORY OF VIDEO GAMES 1972 The Magnavox Odyssey, the first at-home gaming system, is introduced. 1997 1969 Dennis “Thresh” Fong Rick Blomme creates wins a Ferrari 328 GTS a two-person version as the grand prize of the of Spacewar! and first Quake tournament, releases it on PLATO.