NZMJ 1507.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017-10-Motor-Mouth

THE VOICE OF THE MACEDON RANGES A ES ND G D N I A A0003800S S R T R N & DISTRICT MOTOR CLUB INC. I C O T D - E I C A0003800S N A C . M M B OTOR CLU DR BLAKE BALLARAT GOLD MUSEUM MID-WEEK RUN 23 AUG 2017 ISSUE: V34-12 – OCTOBER 2017 Club Objective: To encourage the restoration, preservation and operation S AN of motorised vehicles. E D G D N I A A0003800S S R T R N I C O T Meetings: First Wednesday of every month (except Jan) at 8pm. D - E I C N A C . Disclaimer: The opinions and ideas expressed in this magazine are not M necessarily those of the club or the committee. No responsibility can be taken M B OTOR CLU for accuracy of submissions. Committee 2016/2017 President - Alan Martin Vice President - Ted Delia Ph: 0402 708 408 Ph: 0424 244 390 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Secretary-Hanging Rock- Graham Williams Treasurer - Adam Furniss Ph: 0419 393 023 Ph: 0404 034 841 E:[email protected] E: [email protected] Membership Officer/ Members Rally Director– Deb Williams Representative - Michael Camilleri Ph: 0404 020 525 Ph: 0432 718 250 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Sales Officer - Lina Bragato Editor - Peter Amezdroz Ph: 0432 583 098 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] Welfare/Grievance Officer - John Parnis Head Scrutineer Officer Brian- Jayasingha Ph: 0425 802 593 Ph: 9330 3331 BH E: [email protected] Property Officer – Boyd Unwin Catering Officer - Clara Tine Ph: 0403 371 449 Librarian - Shelly Haylock Ph: 0430 426 854 Web Administrator - Andrew Parnis -

Acdelco Premium Belt Range

ACDELCO PREMIUM BELT RANGE ACDELCO BELTS ACDelco P/N GM P/N Application Make/Model FORD (Asia & Oceania) Telstar 2.0 / FORD Australia Laser 1.8 / HONDA Integra 1.8 / MAZDA 323 1.8 / MAZDA 323 Astina 1.8 / MAZDA 323 Protege 1.8 / MAZDA 626 2.0 / MAZDA 626 Estate/Wagon 2.0 / MAZDA 4PK920 19376034 Capella 2.0 / MAZDA Familia 1.8 / MAZDA MX6 2.5 / MAZDA Premacy 1.8 / NISSAN Pulsar 2.0 / SUZUKI Alto 1.0 / SUZUKI Cultus 1.0 / TOYOTA Chaser 2.0 / TOYOTA Echo 1.3 / TOYOTA Starlet 1.3 / TOYOTA Supra 3.0 / TOYOTA Yaris 1.3 / TOYOTA Yaris Verso 1.3 FORD (Europe) Fiesta 1.2 / FORD (Europe) Fusion 1.4 / FORD Australia Fiesta 5PK692SF 19375735 1.6 / MAZDA 3 2.0 / MAZDA Axela 2.0 LEXUS ES 300 3.0 / LEXUS RX 300 3.0 / LEXUS RX 330 3.3 / MITSUBISHI Lancer 1.5 / MITSUBISHI Mirage 1.3 / NISSAN 200SX 2.0 / NISSAN 4PK880 19376031 Serena 2.0 / NISSAN Skyline GT-R 2.6 / TOYOTA Avalon 3.0 / TOYOTA Camry 3.0 / TOYOTA Estima 3.0 / TOYOTA Harrier 3.0 / TOYOTA Hiace 2.4 / TOYOTA Kluger 3.3 / TOYOTA Starlet 1.3 HOLDEN Calais 3.6 / HOLDEN Caprice 3.6 / HOLDEN Commodore 3.6 / HOLDEN Crewman 3.6 / HOLDEN Frontera 2.2 / HOLDEN One Tonner 3.6 6PK2045 19376030 / HOLDEN Statesman 3.6 / JEEP Cherokee 3.2 / SUZUKI Grand Vitara 2.4 / SUZUKI SX4 2.0 DAEWOO 1.5i 1.5 / DAEWOO Cielo 1.5 / DAEWOO Lanos 1.5 / HOLDEN Nova 1.4 / SUZUKI Vitara 1.4 / TOYOTA Corolla 1.3 / TOYOTA 5PK970 19376037 Corolla Estate/Wagon 1.6 / TOYOTA Corolla Levin 1.5 / TOYOTA Sprinter 1.6 / TOYOTA Sprinter Carib 1.6 MAZDA 3 2.0 / MAZDA CX3 2.0 / MAZDA CX5 2.0 / MITSUBISHI Galant 6PK965 19376038 2.5 / MITSUBISHI -

Chevrolet Spark Service Manual

1 / 5 Chevrolet Spark Service Manual Complete service repair manual for Chevrolet Spark 2000-2015, with all the workshop information to maintain, troubleshoot, diagnose, repair, and service like .... Oct 11, 2012 — Does anyone know if Chevy has an official service manual available for the USA Sparks yet? This is one of the things I almost always buy as .... 2019 Chevrolet Spark – PDF Owner's Manuals. in English. Owner's Manual. 343 pages. Chevrolet Spark Models. 2021 Chevrolet Spark · 2020 Chevrolet Spark .... Factory service manual for the Chevrolet Spark. The type of information contained in this workshop manual include general servicing, maintenance and minor .... PDF Workshop Service Repair Manuals Find. chevrolet spark Owner s Manual View Fullscreen chevrolet spark Owner s Manual suburan chevy Owner's. Powering the .... Results 1 - 24 of 48 — AutoZone offers Free In-store Pickup for Chevrolet Repair Manual - Vehicle. Order yours online today and pick up from the store.. The service department checked my vehicle out to make sure all fluid levels were in order... They have me information on what I should have done next, .... Chilton's Chevrolet Corsica/Beretta 1988-92 Repair ManualChevrolet. Astro and Gmc Safari Mini-Vans Automotive Repair ManualMotor Auto. Repair Manual. Chevrolet India provides car service and repair manuals which contain all the information about spares parts, car maintenance, car accessories, .... It will totally ease you to look guide chevrolet spark 10 service manual ... Chevrolet Spark 2016 2017 2018 Service Repair Manual PDF Chevrolet Spark .... 2003 Chevy Tracker Auto Repair Manuals — CARiD.com. View and Download Chevrolet TRACKER 2003 manual online. -

MY10 VE and WM PRODUCT INFORMATION 3.0L and 3.6L SIDI

September 2009 MY10 VE and WM PRODUCT INFORMATION 3.0L and 3.6L SIDI V6 Engines Overview The Global V6 engine family was launched by General Motors in 2003 to fulfil its strategy to build a new generation of engines for flexible worldwide application in premium and high- performance vehicles. Today GM Powertrain’s all-alloy 60-degree double overhead cam (DOHC) Global V6 engines power a variety of vehicles around the world. GM Holden is a producer as well as a user of Global V6 engines. In 2003 its newly commissioned $400 million Port Melbourne V6 engine plant began building Global V6 engines for export. In August 2004 Alloytec Global V6 engines were introduced to the Australian market with the Holden VZ Commodore and WL Caprice and Statesman model ranges. The latest evolution of the Global V6 is the Spark Ignition Direct Injection SIDI V6; which offers advanced direct combustion chamber fuel injection. Like its predecessor, the SIDI V6 applies highly developed engine technologies such as state-of- the-art casting processes, full four-cam phasing, ultra-fast data processing and torque-based engine management. GM Holden engineers jointly assisted in the architectural development of the SIDI V6 with colleagues from GM technical centres in North America and Germany. The 3.0L and 3.6L SIDI V6 engines introduced with the MY10 Holden Commodore, Berlina, Calais, Sportwagon, Ute, Statesman and Caprice model ranges combine with smooth-shifting six-speed automatic transmission and dual exhaust specified as standard*. They deliver a balance of improved operating refinement with first-rate noise and vibration control, good specific output, high torque over a broad rpm band, fuel economy and low emissions, exclusive durability-enhancing features and very low maintenance. -

Bathurst 2019 Results Show N Shine

BATHURST 2019 RESULTS SHOW N SHINE CLASS PLACE NO NAME & CAR Top Sedan (Showcar) 2nd 51 Mark Wilson - Holden LH Torana Top Sedan (Showcar) 1st 53 Victor Yeghoyan - Chevrolet 64 Bel Air Top Sedan (Streetcar) 2nd 21 Paul Zammit - Holden Chev Bel Air Top Sedan (Streetcar) 1st 423 Sebastian Desisto - Ford Falcon XW Top Coupe/Tudor (Showcar) 2nd 424 Ken Logue - Holden HT Monaro Top Coupe/Tudor (Showcar) 1st 42 Kevin Couper - Valiant VG Coupe Top Coupe/Tudor (Streetcar) 2nd 41 Adam Griffiths - Ford GT Falcon Top Coupe/Tudor (Streetcar) 1st 636 John Spinks - Holden Torana Top Ute/Pickup (Showcar) 1st 101 Sebastian Desisto - Datsun 1200 Top Ute/Pickup (Streetcar) 1st 512 Ian Granger - Holden Rodeo Top Van/Wagon (Showcar) 1st 645 Phil Kerjean - Holden Commodore Top Van/Wagon (Streetcar) 1st 446 Josh Brian - Holden HG Belmont Top Interior 1st 53 Victor Yeghoyan - Chevrolet 64 Bel Air Top Engineered 1st 45 John Beckingham - Ford Top Standard Paint 1st 41 Adam Griffiths - Ford GT Falcon Top Custom Paint/Special Effects 1st 645 Phil Kerjean - Holden Commodore Top Undercarriage 1st 42 Kevin Couper - Valiant VG Coupe Top Engine Compartment 1st 42 Kevin Couper - Valiant VG Coupe Top Import 1st 30 Brett Doble - Pontiac Top Restored/Authentic 1st 60 Peter Barrett - Holden Torana SLR Top Female Vehicle 1st 304 Sharon Xuereb - Holden 1957 Chev Bel Air Top Custom 1st 43 Darren Gersbach - Holden FX Top Pro Street 1st 45 John Beckingham - Ford Pro’s Choice (GM) 1st 433 Vince D’Amico - Holden Torana Pro’s Choice (Ford) 1st 428 Nick LaBara - Ford 66 Futura Pro’s -

December 2014

December 2014 Website: www.nzmustang.com/Clubs/Canterbury.htm PO Box 22389, Christchurch 8140 - Email: [email protected] Regular Features Club Reports President’s Message Kaikoura Hop Club Captain’s Report Henry Ford Memorial New Members Run Your Committee CONVENTION Advertisements All USA Day Events List Featured this Quarter Honourable Guests Note from abroad Sponsorship Diary THANK YOU TO ALL OUR MAGAZINE SPONSORS who make it possible to bring these printed editions to you: Academy Signs - Avon City Ford - Banks Car Upholstery - Copy Print - Heavy Diesel Parts & Services Hillside ITM Building Centre - Mustang Centre - NZ Tax Refunds - Steve Allan Auto Refinishers - Swann Insurance Jeff & Karen Waghorn Z Branded Service Stations, The Speed Shed Ross Norton and Kevin Rea are proud to sponsor the Canterbury Mustang Owners Club. Canterbury owned and operated and Suppliers of building materials to the Trade and DIY. We’ll see you right From Left: Kevin, Jesse, Josh, Sandra, Paul, Nathan, Shane & Ross Missing: Anna, Gary, Mark, Robbie, Chris, Wade, Matt, Clyde, Elizabeth, Colin, Barb For help & friendly advice with your building project Concrete Steel Timber Frames/Trusses HAVE PLANS? NEED PRICES? Gib Contact: Insulation Gary: 027 272 2231 Roofing Robbie: 027 443 8124 Tiles Ross: 027 407 0407 Hardware Mark: 027 444 4851 Chris: 027 444 4849 Doors Wade: 027 707 9724 Decking Bathrooms Phone: 03 349 9739 Kitchens Fax: 03 349 3098 Paint Email: [email protected] Stain etc http://www.itm.co.nz/hillside Visit us: Corner of Springs Rd & Halswell Junction Rd, Hornby Steve Steele & Sharon Boag 1984 GT 350 Convertible Stewart Kaa & Natividad Kaa-Sanchez - Gary Sim 1966 A Code Notch Back Rodger & Bernadine Atkinson 1973 351 Cleveland Convertible Gerard & Halina Jordan 2011 GT 350 Shelby (45th Anniversary) Mike Stevenson 1997 Cobra 4.6 Peter Barker & Joy Coughlan 2008 Mach Roush 4.6 Rebecca Fuller - Steve & Trudy McLachan 1969 Fastback 351 Erin Jackson - Steve & Ruth Cox 1965 Coupe Gary Fransen 2006 GT 4.6 C. -

GM 2004 Annual Report

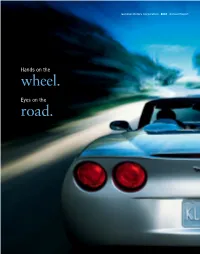

General Motors Corporation 2004 Annual Report Hands on the wheel. Eyes on the road. Contents 2 Financial Highlights 42 Corporate and Social Responsibility 3 Letter to Stockholders 44 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 8 Drive more great new cars and trucks. 59 Independent Auditors’ Report 20 Drive breakthrough technology. 60 Consolidated Financial Statements 26 Drive one company further. 67 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 32 Drive more dreams to reality. 102 Board of Directors and Committees 36 Drive to a bright new future. 104 Senior Leadership Group 40 At a Glance Inside Back Cover General Information We’re on the right road. Our cars and trucks are getting better all the time. Our quality is now back among the best in the industry. We’re stronger and more globally integrated than ever. But it’s not enough. The world is not standing still while we improve. We have to be faster. Bolder. Better. With our hands fi rmly guiding the wheel and eyes focused confi dently on the road ahead, that’s what we’re determined to do. Financial Highlights (Dollars in millions, except per share amounts) Years ended December 31, 2004 2003 2002 Total net sales and revenues $193,517 $185,837 $177,867 Worldwide wholesale sales (units in thousands) 8,241 8,098 8,411 Income from continuing operations $÷÷2,805 $÷÷2,862 $÷÷1,975 (Loss) from discontinued operations – $÷÷÷(219) $÷÷÷(239) Gain on sale of discontinued operations – $÷÷1,179 – Net income $÷÷2,805 $÷÷3,822 $÷÷1,736 Net profi t margin from continuing operations 1.4% 1.5% 1.1% Diluted earnings -

2015 AWARD Name Vehicle PRIZE MONEY SHOW AWARDS Grand Champion * 533 Ralph Italiano 1932 Ford Coupe $ 5,000.00

2015 AWARD Name Vehicle PRIZE MONEY SHOW AWARDS Grand Champion * 533 Ralph Italiano 1932 Ford Coupe $ 5,000.00 STREET MACHINE - Elite Top Judged * 553 Lennard Vidot 1971 Holden Monaro $ 1,000.00 Motorvation Street Machine - Top 10 553 Lennard Vidot 1971 Holden Monaro $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Machine - Top 10 302 Spencer Jarret Holden Commodore VH SLE $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Machine - Top 10 331 Darren Green Holden Torana SS Hatch $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Machine - Top 10 464 Stuart Vernon 1969 Chev Camaro $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Machine - Top 10 329 David Cocciolone Mazda RX2 $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Machine - Top 10 532 Mick Patience 1980 Ford XD $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Machine - Top 10 520 Shane Smart 1976 Holden Torana $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Machine - Top 10 565 David Gibson Holden HQ $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Machine - Top 10 549 Brad Durtanovich 1957 Chev 210 $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Machine - Top 10 39 Patrick Rando 1976 Holden GTS Monaro $ 100.00 STREET ROD - Elite Top Judged * 533 Ralph Italiano 1932 Ford Coupe $ 1,000.00 Motorvation Street Rod - Top 5 533 Ralph Italiano 1932 Ford Coupe $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Rod - Top 5 236 Mark Craine-White Ford Coupe $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Rod - Top 5 253 John Gordon Ford Replica Coupe $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Rod - Top 5 502 Mal Foord Plymouth 1933 Tudor $ 100.00 Motorvation Street Rod - Top 5 288 Tony Fondacaro Ford Tudor $ 100.00 STREET MACHINE - Driven Best Street Machine Driven * 108 Darren Rowe Chevrolet Bel Air $ 100.00 STREET ROD - Driven -

Holden Vehicle Communication Manual (Including Holden Astra, Barina and Vectra Etc.) July 2011

SEE APPLICABLE COVERAGE SHEETS FOR VEHICLE APPLICATIONS Holden Vehicle Communication Manual (Including Holden Astra, Barina and Vectra etc.) July 2011 Use in conjunction with the applicable Scanner User’s Reference Manual and Diagnostic Safety Manual. 1 Before operating this unit, please read this manual and any applicable Scanner User’s Manual. Safety Notices .................................... Refer Diagnostic Safety Manual Quick Reference Contents Listing ... page 5 Using the Scanner Module ............... Refer to relevant User's Manual for more information Vehicles covered and systems covered in all sections of software are available on the applicable coverage sheets. 2 Holden Vehicle Communication Manual (Including Holden Astra, Barina and Vectra etc.) July 2011 BEFORE OPERATING THIS UNIT, PLEASE READ THIS MANUAL CAREFULLY, ALSO PAY PARTICULAR ATTENTION TO THE SAFETY PRECAUTIONS IN THIS MANUAL AND THE DIAGNOSTIC SAFETY MANUAL. 3 The information, specifications, and illustrations in this manual are based on the latest information available at the time of publication. The tool manufacturer and the vehicle manufacturers reserve the right to make equipment changes at any time without notice. All illustrations in this manual are for demonstration purposes only. They are representative images only. They do not portray actual situations and not intended for diagnostic use or actual testing. Copyright © 2010 Snap-on Technologies, Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Quick Reference Contents Detailed Contents are at the beginning of each part Part -

Issue 1-Sept 2020

Issue 1: September 2020 Beginning to Torque Welcome to the first issue of Macaulay Torque, a place for us to share exciting product updates, specials and information about our business and our community with you. As I write this, I’m finding for many business and gramme where we will Service Centre in Wana- it hard to believe it’s Sep- community groups in donate $250 to clubs ka, which will open in the tember already, daylight Southland and Central that we sponsor when coming weeks. See the savings is just around the Otago and at the end of supporters, family and most recent photos of corner and we are keep- lock down we joined the players purchase a new the new site on page 2. ing our fingers crossed to call alongside other busi- or used vehicle. We’ve move down to Alert Level We hope that this news- 1 next week! e’re very aware it has been particularly letter will give you some insights into our busi- tough for many. in Southland and When Covid-19 hit inter- W ness and our great team, nationally, Ford Australia Central Otago and at the end of lock down we along with the opportu- redeployed their resourc- joined. other businesses in the community nity to grab some great es and produced face and encouraged people to support local. deals and see more infor- shields, which they dis- mation about our fantas- tributed to dealerships tic product range. throughout the world. nesses in the community been blown away by the We were thrilled to be A big thank you to all our and encouraged people response to this initia- customers for your ongo- able to offer these to lo- to support local. -

Technical Bulletin B32 Holden Commodore Ve/ Calais Sedan and Sportwagon/ Statesman and Caprice Wm Sedan Hsv E-Series Sedan and Sportwagon

TECHNICAL BULLETIN B32 HOLDEN COMMODORE VE/ CALAIS SEDAN AND SPORTWAGON/ STATESMAN AND CAPRICE WM SEDAN HSV E-SERIES SEDAN AND SPORTWAGON REPAIRS TO SPARE WHEEL WELL LUGS USING METAL BRACKETS JULY 2008 Insurance Australia Limited Disclaimer: ABN 11 000 016 722 The information contained herein is for general information purposes only. Users should be aware that (to the maximum permitted AFS Licence No. 227681 by law) we accept no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of any material contained herein and exclude all liability to any person arising directly or indirectly from using the information or material. We recommend users confirm the accuracy and IAG Research Centre appropriateness of the information from another source if necessary, and to exercise their own skill and care with respect to its use. Unit One/ No. 2 Holker Street Copyright Newington NSW 2127 Australia Copyright © 2007 Insurance Australia Limited ABN 11 000 016 722. All content included herein, such as text, documents, graphics, logos and images are the property of Insurance Australia Limited or its content suppliers and protected by Australian T +61 (0)2 9292 6840 copyright laws. Third party copyright and trade marks appearing herein are reproduced with permission. No part of the content F +61 (0)2 9737 9860 may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, commercialised or re-used for any purpose whatsoever without written permission of Insurance Australia Limited (contact IAG Research Centre for more information). E [email protected] W www.iagresearch.com.au Low speed rear impacts can easily damage the spare wheel wells on Holden VE/WM- series and HSV E-series sedans and sportwagons. -

Holden VF Commodore, Sportwagon and Calais

Sedan Sportwagon Commodore WHEN WE IMAGINED THE VF COMMODORE WE IMAGINED A WHOLE NEW WORLD This is one of those When you proudly wear your heart on your sleeve, knowing moments. A line in the that you’re the rival of any. sand type of moment. It’s not ego-driven. It simply comes from a desire to be the best at what you do. And that’s to design a car for Australia and the world. That changes perceptions. That redefines its class. Welcome to the Holden Commodore. WELCOME TO THE HOLDEN COMMODORE. Calais V-Series Sedan in Prussian Steel Calais V-Series Sedan interior in Light Titanium * Available on automatic models only # Driver remains responsible for vehicle control ^ Not available on Evoke, standard on all other models + Standard on Calais, Calais V-Series, SS V-Series and SSV Redline WE CREATED A CAR Never before has a Commodore been so aware of Remote vehicle Passive Entry and Automatic Park Assist Rear View Camera Reverse Traffic Alert^ + its surroundings; and so in tune with the driver. start system* Push-button Start Leading from the front When you shift into When reversing, it’s Remote vehicle start gets This ultra-convenient is the all-new Automatic reverse, the Rear View not always easy to see IN TOUCH WITH The Commodore is one of the most advanced you on your way quicker, feature offers push-button Park Assist, that uses Camera automatically what’s coming up behind enabling you to fire up the ignition and the ability to ultrasonic sensors to comes to life, displaying you.