Alabaster, Developing an Outstanding Core Collection, Ch.4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection Development Policy Statement Rare Books Collection Subject Specialist Responsible

Collection Development Policy Statement Rare Books Collection Subject Specialist responsible: Doug McElrath, 301‐405‐9210, [email protected] I. Purpose The Rare Books Collection in the University of Maryland Libraries preserves physical evidence of the most successful format for recording and disseminating human knowledge: the printed codex. From the invention of printing with movable type in Asia to its widespread adoption and explosive growth in 15th century Europe, the printed book in all its forms has had an inestimable impact on the way information has been organized, spread, and consumed. The invention of printing is one of the critical technological advances that made possible the modern world. At the University of Maryland, the Rare Books Collection serves multiple purposes: As a teaching collection that preserves physical examples of the way the book has evolved over the centuries, from a hand‐crafted artifact to a mass‐produced consumable. As a research collection for targeted concentrations of printed text supporting scholarly investigation (see collection scope below). As an historical repository for outstanding examples of human accomplishment as preserved in printed formats, including seminal works in the arts, humanities, social sciences, physical and biological sciences. As a research repository for noteworthy examples of the art and craft of the book: typography, bindings, paper making, illustration, etc. As a secure storehouse for works that because of their scarcity, fragility, age, ephemerality, provenance, controversial content, or high monetary value are not appropriate for the general circulating collection. The Rare Books Collection seeks to enable researchers to interact with the physical artifact as much as possible. -

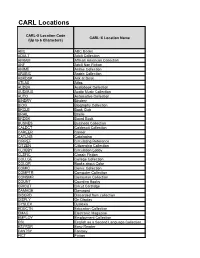

CARL Locations

CARL Locations CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) ABC ABC Books ADULT Adult Collection AFRAM African American Collection ANF Adult Non Fiction ANIME Anime Collection ARABIC Arabic Collection ASKDSK Ask at Desk ATLAS Atlas AUDBK Audiobook Collection AUDMUS Audio Music Collection AUTO Automotive Collection BINDRY Bindery BIOG Biography Collection BKCLB Book Club BRAIL Braille BRDBK Board Book BUSNES Business Collection CALDCT Caldecott Collection CAREER Career CATLNG Cataloging CIRREF Circulating Reference CITZEN Citizenship Collection CLOBBY Circulation Lobby CLSFIC Classic Fiction COLLGE College Collection COLOR Books about Color COMIC Comic Collection COMPTR Computer Collection CONSMR Consumer Collection COUNT Counting Books CRICUT Cricut Cartridge DAMAGE Damaged DISCRD Discarded from collection DISPLY On Display DYSLEX Dyslexia EDUCTN Education Collection EMAG Electronic Magazine EMPLOY Employment Collection ESL English as a Second Language Collection ESYRDR Easy Reader FANTSY Fantasy FICT Fiction CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) GAMING Gaming Collection GENEAL Genealogy Collection GOVDOC Government Documents Collection GRAPHN Graphic Novel Collection HISCHL High School Collection HOLDAY Holiday HORROR Horror HOURLY Hourly Loans for Pontiac INLIB In Library INSFIC Inspirational Fiction INSROM Inspirational Romance INTFLM International Film INTLNG International Language Collection JADVEN Juvenile Adventure JAUDBK Juvenile Audiobook Collection JAUDMU Juvenile Audio Music Collection -

Read-Aloud Chapter Books for Younger Children for Children Through 3 Rd Grade Remember to Choose a Story That You Will Also Enjoy

Read-Aloud Chapter Books for Younger Children rd for children through 3 grade Remember to choose a story that you will also enjoy The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken: Surrounded by villains of the first order, brave Bonnie and gentle cousin Sylvia conquer all obstacles in this Victorian melodrama. Poppy by Avi: Poppy the deer mouse urges her family to move next to a field of corn big enough to feed them all forever, but Mr. Ocax, a terrifying owl, has other ideas. The Indian in the Cupboard by Lynne Reid Banks: A nine-year-old boy receives a plastic Indian, a cupboard, and a little key for his birthday and finds himself involved in adventure when the Indian comes to life in the cupboard and befriends him. Double Fudge by Judy Blume: His younger brother's obsession with money and the discovery of long-lost cousins Flora and Fauna provide many embarrassing moments for twelve-year-old Peter. The Mouse and the Motorcycle by Beverly Cleary: A reckless young mouse named Ralph makes friends with a boy in room 215 of the Mountain View Inn and discovers the joys of motorcycling. How to Train Your Dragon by Cressida Cowell : Chronicles the adventures and misadventures of Hiccup Horrendous Haddock the Third as he tries to pass the important initiation test of his Viking clan, the Tribe of the Hairy Hooligans, by catching and training a dragon. Understood Betsy by Dorothy Canfield Fisher: Timid and small for her age, nine- year-old Elizabeth Ann discovers her own abilities and gains a new perception of the world around her when she goes to live with relatives on a farm in Vermont. -

Printing Presses in the Graphic Arts Collection

Printing Presses in the Graphic Arts Collection THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY 1996 This page blank Printing Presses in the Graphic Arts Collection PRINTING, EMBOSSING, STAMPING AND DUPLICATING DEVICES Elizabeth M. Harris THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON D.C. 1996 Copies of this catalog may be obtained from the Graphic Arts Office, NMAH 5703, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 20560 Contents Type presses wooden hand presses 7 iron hand presses 18 platen jobbers 29 card and tabletop presses 37 galley proof and hand cylinder presses 47 printing machines 50 Lithographic presses 55 Copperplate presses 61 Braille printers 64 Copying devices, stamps 68 Index 75 This page blank Introduction This catalog covers printing apparatus from presses to rubber stamps, as well as some documentary material relating to presses, in the Graphic Arts Collection of the National Museum of American History. Not listed here are presses outside the accessioned collections, such as two Vandercook proof presses (a Model 4T and a Universal III) that are now earning an honest living in the office printing shop. At some future time, no doubt, they too will be retired into the collections. The Division of Graphic Arts was established in 1886 as a special kind of print collection with the purpose of representing “art as an industry.” For many years collecting was centered around prints, together with the plates and tools that made them. Not until the middle of the twentieth century did the Division begin to collect printing presses systematically. Even more recently, the scope of collecting has been broadened to include printing type and type-making apparatus. -

Library of Congress Collection Overviews: Rare Books

COLLECTION OVERVIEW RARE BOOKS I. SCOPE This overview describes the holdings of the Rare Books and Special Collections Division (RBSCD)of the Library of Congress. It excludes rare books and manuscripts in the custody of other Library divisions, such as the Music Division, the Asian Division, or the African and Middle Eastern Division. In general, all materials printed before 1801 fall into the scope of RBSCD. Although the division’s materials come into its custody for a variety of reasons – age, rarity, monetary value, importance in the history of printing, historic binding, provenance or association interest, fragility, uniqueness or scarcity – they have one point in common: the collections document at a research level the traditions of thought and learning and the social life and customs of Europe and the Americas. II. SIZE The Rare Book and Special Collections Division's holdings amount to approximately 800,000 books, broadsides, pamphlets, theater programs and playbills, title pages, prints, posters, photographs, and medieval and Renaissance manuscripts. III. GENERAL RESEARCH STRENGTHS The Division selects rare materials and special collections covering all eras and subjects, focusing on original printed sources in the following areas: the fifteenth-century book and the history of printing, European social and intellectual history, the Reformation, the history of science, travels and voyages, the illustrated book, Mesoamerica and the encounter, Americana, selected English and American authors, the fine press tradition, the contemporary artist’s book, subject themes and formats such as gastronomy and magic, and special format books such as miniature books. Criteria for the selection of rare materials and special collections include especially their long-term scholarly importance and their value as editions of a given work. -

Rare Books and Special Collections Collection Development Policy January 2020 I. Introduction Rare Books and Special Collections

Rare Books and Special Collections Collection Development Policy January 2020 I. Introduction Rare Books and Special Collections at Northern Illinois University Library includes those materials that, because of subject coverage, rarity, source, condition, or form, are best handled separately from the General Collection. The primary materials held in RBSC are an integral part of the educational experience, in keeping with the public research and teaching missions of Northern Illinois University. We provide students, faculty, staff, and individual users from the general public at all levels an opportunity to interact with hands-on history, and to perform in- depth research, particularly in areas related to popular culture in the United States. The nature, extent, and depth of the collection have grown with that purpose to date, although the nature of the collections is always subject to review and extension depending on the research needs of the entire community. II. Criteria for Consideration for Inclusion in the Rare Books Collection (over 10,300 vols.) All inclusion decisions are ultimately made by the Curator on a case-by-case basis. Materials that meet these guidelines are not guaranteed to be accepted into the Rare Books Collection; the Curator may opt not to add particular items due to condition, space issues, or other considerations. A. Date of Publication. The simplest general guideline for materials to be included is the publication date of the book. The cut-off dates for inclusion of material with various imprints are listed below with a brief explanation of the choice of date: 1. European publications before 1801. Teaching examples of representative types of publications from this period should be sought after (i.e. -

Poetry, Novel, Children's Picture Book, and Memoir Writing Project Faqs for 2020

Poetry, Novel, Children’s Picture Book, and Memoir Writing Project FAQs for 2020 How much do I need to have spent writing already? If you’re considering one of the year-long writing projects, you ought to have spent countless hours working on your craft. Though there’s no clear definition of what “countless hours” means, the best qualified candidates will likely have written many short stories, poems, picture books, or creative nonfiction pieces, given writing a novel, poetry collection, picture book, or memoir serious consideration and/or effort, and of course have spent years of their life reading. HOWEVER, there are those rare exceptions of writers who have not spent years honing their craft who would still be a good fit for this endeavor. If you have questions about your ability, please contact the teaching artist or The Loft for advice. How much commitment is required? By far the most important quality of the prospective student is this: How hard are you willing to work? If the answer to this question is: As hard as I have to in order to finish a collection of poetry, a novel, several picture books, or a memoir in the next year, then you’re probably a good candidate. How will the variances in abilities in the class be accounted for? What if I’m by far the best or worst writer to sign up, won’t that put me at an advantage or disadvantage? As in any writing workshop environment, there are going to be students who are further advanced or more naturally gifted than others. -

Popular Fiction 1814-1939: Selections from the Anthony Tino Collection

POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION L.W. Currey, Inc. John W. Knott, Jr., Bookseller POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION WINTER - SPRING 2017 TERMS OF SALE & PAYMENT: ALL ITEMS subject to prior sale, reservations accepted, items held seven days pending payment or credit card details. Prices are net to all with the exception of booksellers with have previous reciprocal arrangements or are members of the ABAA/ILAB. (1). Checks and money orders drawn on U.S. banks in U.S. dollars. (2). Paypal (3). Credit Card: Mastercard, VISA and American Express. For credit cards please provide: (1) the name of the cardholder exactly as it appears on your card, (2) the billing address of your card, (3) your card number, (4) the expiration date of your card and (5) for MC and Visa the three digit code on the rear, for Amex the for digit code on the front. SALES TAX: Appropriate sales tax for NY and MD added. SHIPPING: Shipment cost additional on all orders. All shipments via U.S. Postal service. UNITED STATES: Priority mail, $12.00 first item, $8.00 each additional or Media mail (book rate) at $4.00 for the first item, $2.00 each additional. (Heavy or oversized books may incur additional charges). CANADA: (1) Priority Mail International (boxed) $36.00, each additional item $8.00 (Rates based on a books approximately 2 lb., heavier books will be price adjusted) or (2) First Class International $16.00, each additional item $10.00. (This rate is good up to 4 lb., over that amount must be shipped Priority Mail International). -

Next Page Foundation Annual Report 2011

NEXT PAGE FOUNDATION ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION On December 8, 2011, Next Page Foundation turned 10. For the last 10 years, the Foundation had supported over 300 publications on key political topics or in underrepresented languages, in print and electronic formats, in 22 languages; commissioned and distributed 38 studies on various aspects of book publishing and translations; supported the establishment of exchange networks between publishers from “peripheral” languages; organized and participated in 50+ events and worked on numerous other projects in over 20 countries. Examples of some of Next Page’s most interesting projects can be seen on the special birthday main page of our website: www.npage.org None of this would have been possible without the support of our staff and partners around the world. We are thankful for the inspiration, energy, professional competence, trust, attitude and cooperation to: Our former staff members who are currently spread over on three different continents and pursuing successful careers; Our interns and volunteers who have learned a lot but also taught us a lot; Our board members who have inspired us and opened new horizons; Our donors who have trusted us and still do; Our grantees who always serve as a precious reality check; Our consultants in Belgrade, Cairo, London, Sarajevo, Vienna, Kuwait City and many other places in Europe and beyond; Our partner organizations who have shared with us responsibility, experience and great satisfaction; And last, but definitely not least, all our friends − for their support and inspiration! ANNUAL REPORT 2011 CONTENTS CONTENTS I. ACTIVITIES & OUTCOMES ............................................................................ -

Self-Publishing and Collection Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Robert P

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 9-15-2015 Self-Publishing and Collection Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Robert P. Holley Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, and the Collection Development and Management Commons Recommended Citation Holley, Robert P., Self-Publishing and Collection Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries. (2015). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Self-Publishing and Collection Development Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences Editorial Board Shin Freedman Tom Gilson Matthew Ismail Jack Montgomery Ann Okerson Joyce M. Ray Katina Strauch Carol Tenopir Anthony Watkinson Self-Publishing and Collection Development Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries Edited by Robert P. Holley Charleston Insights in Library, Archival, and Information Sciences Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright 2015 by Purdue University. All rights reserved. Cataloging-in-Publication data on file at the Library of Congress. Contents Foreword i Mitchell Davis (BiblioLabs) Introduction 1 Robert P. Holley (Wayne State University) 1 E-Book Self-Publishing and the Los Gatos Library: A Case Study 5 Henry Bankhead (Los Gatos Library) 2 Supporting Self-Publishing and Local Authors: From Challenge to Opportunity 21 Melissa DeWild and Morgan Jarema (Kent District Library) 3 Do Large Academic Libraries Purchase Self-Published Books to Add to Their Collections? 27 Kay Ann Cassell (Rutgers University) 4 Why Academic Libraries Should Consider Acquiring Self-Published Books 37 Robert P. -

AFRICA ASSERTS ITS IDENTITY Part I: the Frankfurt Book Fair by Barbara Harrel I-Bond

AFRICA ASSERTS ITS IDENTITY Part I: The Frankfurt Book Fair by Barbara Harrel I-Bond he 1980 Frankfurt Book Fa17focused on :mks "punten and published in Africa " :lacy participants got t3eir first exposure to ?t? richness and divers~tyof Afr~can terature. desp~tethe problems - largely ,-r-3. n,ornic - that ~nhibitAfrica's pubiishing ?,^!ustry The American Universities Field INSTITUTIONAL MEMBERS Staff, Inc.,founded in 1951, is a non- University of Alabama American profit, membership corporation of Brown University Americ/an educational institutions. It California State Universities- employs a full-time staff of foreign area specialists who write from University/Fullerton abroad and make periodic visits to California State Field Staff member institutions. AUFS serves UniversityINorthridge the public through its seminar pro- Dartmouth College grams, films, and wide-ranging pub- Indiana University lications on significant develop- Institute for Shipboard ments in foreign societies. Education University of Kansas Michigan State University University of Pittsburgh Ramapo College of New Jersey Utah State University University of Wisconsin System AUFS Reports are a continuing Associates of the Field Staff are series on international affairs and chosen for their ability to cut across major global issues of our time. the boundaries of the academic dis- Reports have for almost three ciplines in order to study societies in decades reached a group of their totality, and for their skill in col- readers-both academic and non- lecting, reporting, and evaluating academic-who find them a useful data. They combine long residence source of firsthand observation of abroad with scholarly studies relat- political, economic, and social trends ing to their geographic areas of in foreign countries. -

Rare Books Collection Development Policy

Rare Books Collection Development Policy Stephanie Noell, Special Collections Librarian Purpose: This policy is intended to provide guidelines for developing UTSA’s rare book holdings for the next five years (2020-2025), at which time it will be fully reviewed. Our Vision is to bring national recognition to the university for distinctive research collections documenting the diverse histories and development of San Antonio and South Texas. Our Mission is to build, preserve, and provide access to distinctive archival, photographic, and printed materials, with a particular commitment to collections with significance to our region. We embrace the changing digital landscape by actively exploring new ways to enhance access to our collections. We support the university’s ascent to Tier One status by building nationally recognized collections that inspire new knowledge, serving researchers at UTSA and from around the world. Statement of Purpose In support of the UTSA Libraries’ goal of building, preserving, and digitizing distinctive collections of national importance, the Special Collections Librarian seeks to collect, preserve, and provide access to material documenting the history and culture of South Texas and Mexico. Particular attention will be given to material that is deemed exceptional due to its content, publishing history, provenance, age, format, significance, rarity, or vulnerability. Preservation of the collection includes both environmental controls and item-level conservation. Access to research materials is provided through cataloging, online guides, digital facsimiles, onsite assistance, outreach programs, and partnering with faculty to provide instruction for specific subjects or classes. Introduction The Rare Books Unit serves as the repository for published—and occasionally unpublished—codices, maps, and ephemera in the Special Collections Department.