Grassroots Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Florida Women's Heritage Trail Sites 26 Florida "Firsts'' 28 the Florida Women's Club Movement 29 Acknowledgements 32

A Florida Heritag I fii 11 :i rafiM H rtiS ^^I^H ^bIh^^^^^^^Ji ^I^^Bfi^^ Florida Association of Museums The Florida raises the visibility of muse- Women 's ums in the state and serves as Heritage Trail a liaison between museums ^ was pro- and government. '/"'^Vm duced in FAM is managed by a board of cooperation directors elected by the mem- with the bership, which is representa- Florida tive of the spectrum of mu- Association seum disciplines in Florida. of Museums FAM has succeeded in provid- (FAM). The ing numerous economic, Florida educational and informational Association of Museums is a benefits for its members. nonprofit corporation, estab- lished for educational pur- Florida Association of poses. It provides continuing Museums education and networking Post Office Box 10951 opportunities for museum Tallahassee, Florida 32302-2951 professionals, improves the Phone: (850) 222-6028 level of professionalism within FAX: (850) 222-6112 the museum community, www.flamuseums.org Contact the Florida Associa- serves as a resource for infor- tion of Museums for a compli- mation Florida's on museums. mentary copy of "See The World!" Credits Author: Nina McGuire The section on Florida Women's Clubs (pages 29 to 31) is derived from the National Register of Historic Places nomination prepared by DeLand historian Sidney Johnston. Graphic Design: Jonathan Lyons, Lyons Digital Media, Tallahassee. Special thanks to Ann Kozeliski, A Kozeliski Design, Tallahassee, and Steve Little, Division of Historical Resources, Tallahassee. Photography: Ray Stanyard, Tallahassee; Michael Zimny and Phillip M. Pollock, Division of Historical Resources; Pat Canova and Lucy Beebe/ Silver Image; Jim Stokes; Historic Tours of America, Inc., Key West; The Key West Chamber of Commerce; Jacksonville Planning and Development Department; Historic Pensacola Preservation Board. -

Florida Libraries

The information in this publication represents only a small sample of all the archival and special environment-related collections available online or at south Florida (and beyond) libraries, museums and organizations. Researchers, students and the general public should note the names of institutions possessing the original materials and contact these organizations directly for information on reproductions, copyright, research assistance, and reading room hours. I speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues. Dr. Seuss (1904 - 1991), The Lorax Gail Donovan, Librarian, New College of Florida, Jane Bancroft Cook Library (As of February 2014, Mote’s Archivist) Mote Marine Laboratory, Arthur Vining Davis Library & Archives Susan Stover, Library & Archives Director and Erin Mahaney, Archivist Daniel Newsome and Marissa Brady, Mote Library interns Kay Hale, Mote Library volunteer We are grateful to our many library and archives colleagues throughout Florida for sharing their information and ideas. Mote Marine Laboratory Technical Report No. 1722 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 2 Trends in Environmentalism 10 a) Naturalists/Early Conservationists b) Conservationists/Preservationists c) Environmentalists Key Events in Florida’s Environmental History 14 e.g. The Swamp and Overflowed Lands Act of 1850 Great Giveaway-Reclamation Act Archival and Special Collections ….mainly print 18 Digital Collections (non-government) 73 Government Agencies (local, state, federal) 77 Plants and Herbariums 92 Facilities and Organizations 100 … whose mission -

The 2020 Induction Ceremony Program Is Available Here

FLORIDA WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME VIRTUAL INDUCTION CEREMONY honoring 2020 inductees Alice Scott Abbott Alma Lee Loy E. Thelma Waters Virtual INDUCTION 2020 CEREMONY ORDER OF THE PROGRAM WELCOME & INTRODUCTION Commissioner Rita M. Barreto . 2020 Chair, Florida Commission on the Status of Women CONGRATULATORY REMARKS Jeanette Núñez . Florida Lieutenant Governor Ashley Moody . Florida Attorney General Jimmy Patronis . Florida Chief Financial Officer Nikki Fried . Florida Commissioner of Agriculture Charles T. Canady . Florida Supreme Court Chief Justice ABOUT WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME & KIOSK Commissioner Maruchi Azorin . Chair, Women’s Hall of Fame Committee 2020 FLORIDA WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME INDUCTIONS Commissioner Maruchi Azorin . Chair, Women’s Hall of Fame Committee HONORING: Alice Scott Abbott . Accepted by Kim Medley Alma Lee Loy . Accepted by Robyn Guy E. Thelma Waters . Accepted by E. Thelma Waters CLOSING REMARKS Commissioner Rita M. Barreto . 2020 Chair, Florida Commission on the Status of Women 2020 Commissioners Maruchi Azorin, M.B.A., Tampa Rita M. Barreto, Palm Beach Gardens Melanie Parrish Bonanno, Dover Madelyn E. Butler, M.D., Tampa Jennifer Houghton Canady, Lakeland Anne Corcoran, Tampa Lori Day, St. Johns Denise Dell-Powell, Orlando Sophia Eccleston, Wellington Candace D. Falsetto, Coral Gables Rep. Heather Fitzenhagen, Ft. Myers Senator Gayle Harrell, Stuart Karin Hoffman, Lighthouse Point Carol Schubert Kuntz, Winter Park Wenda Lewis, Gainesville Roxey Nelson, St. Petersburg Rosie Paulsen, Tampa Cara C. Perry, Palm City Rep. Jenna Persons, Ft. Myers Rachel Saunders Plakon, Lake Mary Marilyn Stout, Cape Coral Lady Dhyana Ziegler, DCJ, Ph.D., Tallahassee Commission Staff Kelly S. Sciba, APR, Executive Director Rebecca Lynn, Public Information and Events Coordinator Kimberly S. -

Florida Gator Magazine

SPRING 2020 GATOR INVENTORS TO THE RESCUE Plastics that decompose in landfills? Seriously, these new UF ideas are game changers. Page 26 AND THE AWARD GOES TO ... Find out who won this year's Academy of Golden Gators. Page 44 THIS GATOR'S A IT'S EASY TO GET EXCITED ABOUT ANIMALS WITH THIS NAT GEO WILD STAR. Page 20 CORONAVIRUS In early March, due to the spread of COVID-19, all state individuals who embrace new challenges with optimism universities including UF moved all classes online and and demonstrate grace under pressure each day. FLORIDA GATOR asked students to return to their homes. The University of Florida’s This issue, which was going to press as the crisis unfolded, alumni magazine Around the world, this pandemic has created uncertainty includes a revised letter from President Fuchs (pg. 5), as VOLUME 7 ISSUE 4 SPRING 2020 and will surely be remembered as an inflection point that well as photos from campus as staff and students headed VICE PRESIDENT, UF ADVANCEMENT challenged all members of our community to rethink home (pg. 74). Your summer issue will include complete Thomas J. Mitchell the way we approach our daily lives and work. I thank coverage. Until then, remember: “In all kinds of weather, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, everyone for their efforts, patience and flexibility as we we all stick together.” UF ALUMNI ASSOCIATION FEATURES navigate this complex situation together. Matthew Hodge — Matthew Hodge, Executive Director UF ALUMNI ASSOCIATION 20 The Untamable Filipe DeAndrade The strength of our university and Gator Nation is built UF Alumni Association EXECUTIVE BOARD on its people, and I am grateful to be surrounded by President Katrina Rolle This Nat Geo Wild filmmaker’s images are getting humans psyched President-elect Mark Criser Vice President James Gadsby about protecting the many wild creatures in their own backyards. -

Mary Etta Hancock Cubberly Emeritus Board Members David Auth, Ph.D

Matheson History Museum Fall 2015 Newsletter Volume 17, Issue 2 2015 Board of Directors Betsy Albury—President Barry Baumstein—Vice President Lawrence Lokken, J.D.—Treasurer Ivy Bell—Secretary Peggy Macdonald, Ph.D.—Executive Director Robert P. Ackerman, Esq. Larry Brasington Mae Clark Fletcher Crowe, Ph.D. Phil DeLaney Caleb King, D.D.S., M. Sc.D. Rod McGalliard, Esq. Anson Moye, Ph.D. Laura Nemmers Church Street, Archer postcard courtesy of the Matheson History Museum Collection Jon Sensbach, Ph.D. Anita Spring, Ph.D. Courtney Taylor, Ph.D. Greg Young Mary Etta Hancock Cubberly Emeritus Board Members David Auth, Ph.D. By Joanna Grey, Marketing and Education Coordinator Mark V. Barrow, M.D., Ph.D. Mary Etta Hancock Cubberly was a renaissance woman. She was born on April 4, 1870, in Central Donald Caton, M.D. Mine, Michigan, a town known for its copper mine, but her family moved to Archer, Florida, in 1885. According to the 1880 census, her father, James Hancock, had been a blacksmith but when they Mary Ann H. Cofrin moved to Florida he bought over 100 acres of orange trees. Unfortunately, the Big Freeze of 1886 D. Henrichs happened the next year and by the 1900 census Mr. Hancock had become a “well borer.” Rebecca Nagy, Ph.D. Mary Etta was a very smart and determined young woman and in 1886 she began teaching at the age Ann Smith, R.N. of 16. She taught in a one-room log cabin “deep in the country […] and not many miles from the Suwanee River.” She boarded with the Snyder family and was introduced to snuff for the first time, although she politely turned it down. -

Florida Lecture Series the Lawton M

The Lawton M. Chiles, Jr. Center for Florida History 2014 –2015 Florida Lecture Series The Lawton M. Chiles, Jr. Center for Florida History Founded in 2001, the Lawton M. Chiles, Jr., Center for Florida History strives to enhance the teaching, study, and writing of Florida history. The center seeks to preserve the state’s past through cooperative eff orts with historical societies, preservation groups, museums, public programs, media, and interested persons. This unique center, housed in the Sarah D. and L. Kirk McKay, Jr., Archives Center, is a source of continuing information created to increase appreciation for Florida history. About the Lecture Series In its 18th year, the Florida Lecture Series is a forum that brings speakers to the Florida Southern College campus to explore Florida life and culture from a wide range of disciplines, including history, public aff airs, law, sociology, criminology, anthropology, literature, and art. The overall objective of the series is to bring members of the community, the faculty, and the student body together to interact with and learn from leading scholars in their fi elds. Board of Governors Dr. James M. Denham, Executive Director Mrs. Mimi Hardman, Lake Wales Mr. Hollis H. Hooks, Lakeland Mr. Kent Lilly, Lakeland Dr. Sarah D. McKay, Lakeland Professor Walter W. Manley II, Tallahassee The Hon. Adam Putnam, Bartow The Hon. Susan Roberts, Lakeland The Hon. Dr. T. Terrell Sessums, Tampa On the Cover Ogeechee Tupelo Photo by Carlton Ward Jr / CarltonWard.com. The 2014–2015 Florida Lecture Series is sponsored in part by WUSF Public Media. Stahl Lecture in Criminal Justice SEPTEMBER 18 CARLTON WARD, JR. -

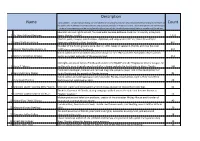

Name Description Count

Description Name (DISCLAIMER: The descriptions below are intended to be very brief summaries of accomplishments provided by members of Count the public who submitted recommendations, and accounts provided in historical record. These descriptions are not intended to be all-encompassing and do not reflect the official view of the Florida Department of State or members of the ad hoc Educator and civil rights activist, founded whatcommittee.) became Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona 1 Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune Beach, Florida, in 1904. 1,233 Teacher, poet, essayist, social activist, diplomat, and song writer Lift Ev'ry Voice; First African 2 James Weldon Johnson American admitted to the Florida Bar. 447 Founder of the Publix grocery store chain in 1930, based in Lakeland, Florida, and now has over 3 George Washington Jenkins, Jr. 1,000 stores across the Southeast. 417 Noted author and environmentalist, best known for her 1947 work The Everglades: River of Grass 4 Marjory Stoneman Douglas and as an ardent defender of the environment. 261 Civil rights activist in Central Florida and active in the NAACP and the Progressive Voters’ League, he 5 Harry T. Moore and his wife were tragically murdered after a bomb exploded in their home in Mims, Florida. 189 Prominent developer, hotelier and railroad magnate; played a major role in the development of 6 Henry Morrison Flagler South Florida and the growth of Florida tourism. 82 Noted author and anthropologist from Eatonville, Florida, most famous work is Their Eyes Were 7 Zora Neale Hurston Watching God, published in 1937. 68 8 Seminole Leader Osceola (Billy Powell) Seminole leader and commander who led troops during the Second Seminole War. -

Summer 2016 Vol

Summer 2016 Vol. 50, No. 4 ONLINE aejmc.us/history INSIDE THIS ISSUE Newsletter of the History Division of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication On to Minneapolis! Early registration for the 2016 AEJMC Conference in Minneapolis ends July 8. The dates are August 4-7 (with Pre-Conference workshops on Wednesday, August 3). The confer- ence theme: Innovate, Integrate, Engage. Accepted papers from the History Division are listed in Mike Sweeney’s column inside on p. 5. Congratulations, all. History Division Program on p. 6. Prof. Finis Dunaway’s book, Seeing Green, won the History Division’s Book Award for 2016. An excerpt begins on Page 13. PF&R Column I PAGES 3-4 AEJMC Conference Papers List I PAGE 5, 7 2016 Conference Program I PAGE 6-7 Membership Column I PAGE 8 NOTES FROM THE CHAIR The Periodical Room For a more inclusive history Essay I PAGE 9 A few months ago, I visited the Ar- and the study of the sea turtle. What Graduate Liaison chie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research was not mentioned in the film, or really Column I PAGE 10 in nearby Mel- at the Center, was Marjorie Harris Carr. Kimberly Wilmot bourne, Flori- Yet without her, Archie Carr would not Teaching Standards Voss da. The Center have achieved as much professionally or Column I PAGES 11-12 included a short personally. They had a 50-year scientific film about the partnership and a marriage that pro- 2016 Book Award Winner acclaimed scien- duced five children. Announcement I PAGE 12 tist for whom the The story of Archie Carr’s wife can Seeing Green Center is named be found in Peggy Macdonald’s book, Book Excerpt I PAGE 13-15, 18 and it included Marjorie Harris Carr: Defender of a clip featuring Florida’s Environment. -

Jennings Lesson

America's Swamp: The Historical Everglades Lesson Plan Created by Rebecca Fitzsimmons May Mann Jennings and the Everglades Postcard of Royal Palm State Park, not dated, (“Postcards (Royal Palm Postcard of Royal Palm State Park (back), not dated, (“Postcards (Royal Park)” folder, May Mann Jennings Papers) Palm Park)” folder, May Mann Jennings Papers) http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00091225/00001/11x http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00091225/00001/12x Grade 4: This lesson will begin by teaching students about the Everglades and include history related to the formation of the Everglades National Park. The role of May Mann Jennings and the Florida Federation of Women's Clubs in forming the Royal Palm State Park will be discussed. This will lead to a study of Jennings' role as an influential citizen, and to a study of other influential Florida women. Objectives: Students will: . Gain an understanding of how civic leaders can make important social changes. Learn about May Mann Jennings and her impact on the establishment of the Royal Palm State Park. Create a biographical timeline of an important Florida historical figure . Learn about the Everglades ecosystem and associated issues Time and Resources: . 6 forty-minute classes . Computers with Internet access . Library materials . Everglades book by Jean Craighead George . Everglades Forever: Restoring America's Great Wetland book by Trish Marx . Colored pencils or markers . 18 x 24 Poster board or paper America's Swamp: The Historical Everglades Lesson Plan Created by Rebecca Fitzsimmons Sunshine State Standards (grade 4) Social Studies: . American History, Standard 1: Historical Inquiry and Analysis o SS.4.A.1.1 Analyze primary and secondary resources to identify significant individuals and events throughout Florida history. -

From Exploitation to Conservation a History of the Marjorie Harris Carr Cross Florida Greenway, by Steven Noll and M

Attachment 11 History Report: From Exploitation to Conservation A History of the Marjorie Harris Carr Cross Florida Greenway, by Steven Noll and M. David Tegeder Marjorie Harris Ca rr Cross Florida G r e e n w a y From Exploitation to Conservation: A History of the Marjorie Harris Carr Cross Florida Greenway by Steven Noll and M. David Tegeder August 2003 This publication was produced in partial fulfillment of a Grant between the State of Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Office of Greenways and Trails, and the Department of Landscape Architecture, University of Florida. History Report: From Exploitation to Conservation i i Marjorie Harris Ca rr Cross Florida G r e e n w a y Acknowledgments A project of this magnitude would not have been possible without the help of literally dozens of individuals and organizations not only in the state of Florida but across the country. We would like to thank the staff of the Office of Greenways and Trails in both Tallahassee and Ocala for their assistance, patience, and excitement about our work. Much of the work of this project took place in archives and libraries and we greatly appreciate the help and support of their staffs. Without their assistance this document would be incomplete and much less interesting. As important as our archival research was the fieldwork we did in the Greenway communities. People have opened their homes and offices, as well as spent untold hours over the phone, talking about the history of the Greenway. We would like to thank those individuals who shared with us their time and their memories, and in so doing gave this document its human dimension. -

Ocklawaha River Green and Gold Report Investing in North Florida Waters

Ocklawaha River Green and Gold Report Investing in North Florida Waters A Stimulus-Ready Project Three Rivers, 50+ Springs, One Solution The Ocklawaha, the heart of the Great Florida Riverway, is part of 95 Jacksonville a vast 217-mile system of rivers and springs that flow north from 10 the Green Swamp near Lake Apopka, are fed by Silver Springs, Osceola National Forest St. Johns and continue past Palatka to the Lower St. Johns River estuary Estuary ending at the Atlantic Ocean. The river was unnecessarily dammed Green Cove Springs in 1968 before the Cross Florida Barge Canal was halted. The Atlantic Ocean St. Johns River Rodman/Kirkpatrick Dam devastated over 7,500 acres of wetland Palatka Buckman Lock forest, 20 springs, and 16 miles of the Ocklawaha River. The Cross Florida Barge Canal 75 Rodman Reservoir destruction continues today. Water quality is declining, fueling Welaka 95 blue-green algae events. Thousands of acres of forests are stressed Lower Ocklawaha Silver Springs Rodman / Kirkpatrick Dam and dying upstream and down. The 100-mile St. Johns River Ocala National Forest Ocala Ocklawaha Estuary is being deprived of its full natural water flow. Massive, Preserve invasive aquatic weed blockages make the dammed river an Silver River I-4 unreliable recreation resource. Harris Chain of Lakes 95 Removing a portion of the earthen Rodman/Kirkpatrick dam at 75 the site of the historic river channel will allow access to essential Lake Apopka habitat for hundreds of manatees and bring back migratory Green Swamp fish and shellfish to the Ocklawaha and Silver Springs. It will I-4 reconnect the historic blueway from Lake Apopka near Orlando to the Atlantic Ocean at Jacksonville for outdoor recreation. -

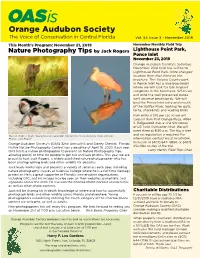

Oasis Editor: Renewables Has Been Gas

NOVEMBER 2019 • 1 OASOAS is is Orange Audubon Society The Voice of Conservation in Central Florida Vol. 54 Issue 3 • November 2019 This Month’s Program: November 21, 2019 November Monthly Field Trip Nature Photography Tips by Jack Rogers Lighthouse Point Park, Ponce Inlet November 23, 2019 Orange Audubon Society’s Saturday, November 23rd field trip will be to Lighthouse Point Park. Note changed location from that listed on the brochure. This Volusia County park in Ponce Inlet has a nice boardwalk where we will look for late migrant songbirds in the hammock. When we exit onto the well-preserved dunes, we’ll observe beach birds. We will bird the Ponce Inlet jetty and mouth of the Halifax River, looking for gulls, terns, shorebirds and wading birds. Park entry is $10 per car, so we will carpool from Port Orange Plaza, 4064 S. Ridgewood Ave. at the SW corner of US 1 and Dunlawton Blvd. We will meet there at 8:30 a.m. The trip is free and no registration is required. For Top left, Bobcat. Right, Young Roseate Spoonbill. Bottom left, Black Skimmer chick with fish. Photos: Jack Rogers information, contact me at lmartin5@ Orange Audubon Society’s (OAS) 32nd Annual Kit and Sidney Chertok Florida msn.com or (407) 647- 5834, or (407) Native Nature Photography Contest has a deadline of April 16, 2020. Each year 252-1182 on day of the trip. OAS hosts a nature photographer to present on Nature Photography Tips, Larry Martin, Field Trips Chair allowing plenty of time for people to get out and take photos.