The Limits of Liberal Planning: the Lindsay Administration's Failed Plan to Control Development on Staten Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary Ann E. Mears 903 Poplar Hill Road Baltimore, Maryland 21210 Phone: 410 435-2265 Website: Email: [email protected]

Mary Ann E. Mears 903 Poplar Hill Road Baltimore, Maryland 21210 Phone: 410 435-2265 Website: www.maryannmears.com email: [email protected] COMMISSIONS: 2015 Petal Play, Columbia Downtown Project, Parcel D, West Promenade, Columbia, MD (interactive, painted aluminum, stainless, water, text, and lighting,14 pieces from 2’ to 28’ height) 2014 Reston Rondo, Reston Town Center, Reston, VA (painted aluminum 18’ h) 2013 Aeriads, Private Residence, Annapolis, MD (exterior relief, painted aluminum 13’ x 3’x 5”) 2013 Charispiral, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston, MA (exterior, painted aluminum, 17’x13’x 8’) 2011 Spun Grace, St. Agnes Hospital, Baltimore, MD (suspended, moving, painted aluminum, 12’x 40’x 30’) 2010 Calla Pods, Private Residence, Baltimore MD (exterior, painted aluminum, 4 forms 3’h - ‘6-6” h) 2009 Lotus Columns, Silver Spring, MD (exterior, eight column forms, stainless 14’ 8”-16’ h) 2009 Sun Drops, Private Residence, Baltimore MD (exterior, painted aluminum, 3 forms 4’h - 5’ h) 2008 Leaps and Bounds, University of Central Florida, Orlando (interior relief, ptd. aluminum 15’x 28’) 2006 Callooh Callay, Millenium Bike Trail, Anne Arundel County, MD (painted aluminum 16’ h) 2004 Floating Garden, Cheverly Health Center, commissioned by the Prince George’s County Revenue Authority, MD (suspended, ptd. aluminum and stainless, 20’x 36’x 44’) 2003 Gyre and Gimble, Betty Ann Krahnke Intermission Terrace, Imagination Stage, Bethesda Academy of Performing Arts, MD (site extends length of a city block, stainless and painted aluminum) -

Columbia Archives Ephemera-Memorabilia-Artifacts Collection

Columbia Archives Ephemera-Memorabilia-Artifacts Collection James W. Rouse's "Photo James W. Rouse's Fishing James W. Rouse's Ice Skates, Shoot" Eyeglasses, n.d. Pole, n.d. n.d. Desk Pen Set Presented to Shovel for Cherry Hill Mall Shovel for The Rouse James W. Rouse from the Expansion Ground Breaking, Company Headquarters Young Columbians, 1975 1976 Ground Breaking, 1972 Whistle Nancy Allison Used Cross Keys Inn Ashtray, n.d. Waterside Restaurant to Summon James W. Rouse Ashtray, n.d. to Meetings, n.d. Columbia Bank and Trust People Tree Ashtray, 1968 Clyde's Restaurant Ashtray, Company Ashtray, 1968 n.d. Columbia All Star Swim Head Ski and Sportswear Columbia Volksmarch Club Meet Badge, n.d. Company Badge, n.d. Badge for Columbia's 20th Birthday, 1987 Columbia Volksmarch Club Town Center 25th Columbia Bank and Trust Badge, 1986 Anniversary Products, 1999 Company Moneybag, n.d. The Mall in Columbia 40th Produce Galore Bag for Kings Contrivance Village Anniversary Shopping Bag, Coffee Beans, 2008 Center Shopping Bag, n.d. 2011 Wilde Lake Village Green Columbia Aquatics Owen Brown Interfaith Holiday Shopping Bag, n.d. Association Swim Bag, n.d. Center Token Noting Surplus Budget, ca. 1984 Hickory Ridge Village Columbia 20th Birthday Rotary Club of Columbia Center Ball, n.d. Balloon, 1987 Town Center Banner, n.d. Rotary Club of Columbia Sewell's Orchards Fruit Sewell's Orchards Fruit Banner, n.d. Basket, n.d. Basket, n.d. www.ColumbiaArchives.org Page 1 Columbia Archives Ephemera-Memorabilia-Artifacts Collection "Columbia: The Next Columbia Voyage Wine Columbia 20th Birthday America Game", 1982 Bottle, 1992 Chateau Columbia Wine Bottle, 1986 Columbia 20th Birthday Santa Remembers Me ™ Merriweather Park at Champagne Bottle, 1987 Bracelet from the Mall Symphony Woods Bracelet, in Columbia, 2007 2015 Anne Dodd for Howard Columbia Gardeners Bumper Columbia Business Card County School Board Sticker, 1974 Case, n.d. -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 16, Number 43, October 27

Deflationaryshock wave hits stock market Western Europe. the key to war or peace Ozone. greenhouse hoaxes exposed in Australia LaRouche: How Congress must act to rebuild after the crash On June 23, 1989 Executive Intelligence Review exposed Henry Kissinger's lucrative interest in keeping the Beijing butchers in power, in "Kissinger' s China card: the drug connection." On September 15, 1989 Wall Street Journal published "Mr. Kissinger Has Opinions-And Business Ties: Commentator Entrepreneur. in Wearing Two Hats. Draws Fire From Critics." where Kissinger's conflict of interest was exposed-without mentioning the heroin trade. I would like to subscribe to Executive Intelligence Review for o 1 year, $396 0 6 months, $225 0 3 months, $ 125 _ I enclose $ check or money _ Name _ ____ _____ ___ _ order _ Address ______________ _ Please charge my o MasterCard 0 Visa City _________State _ Zip __ _ Phone ( Cprd no. _______ Exp. date _______ Make checks payable to EIR New Service Inc., P.O. Box 17390, Signature _______ Washington, D.C. 20041-0390. Founder and Contributing Editor: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. Editor: Nora Hamerman From the Editor Managing Editors: John Sigerson and Susan Welsh Editorial Board: Warren Hamerman, Melvin Klenetsky, Antony Papert, Gerald Rose, Allen Salisbury, Edward Spannaus, Nancy Spannaus, Webster Tarpley, William Wenz, Carol White, Christopher White Science and Technology: Carol White T he dreadful earthquake that shook the San Francisco Bay area, Special Services: Richard Freeman the political tremors rocking Eastern Europe, and the shock wave Book Editor: Katherine Notley Advertising Director: Marsha Freeman which struck the Wall Street markets on Friday Oct. -

Still Here Nearly Three Decades After It Opened in New York’S Battery Park City, This Small Site Continues to Spread Its Influence—And Bring People Joy

STILL HERE NEARLY THREE DECADES AFTER IT OPENED IN NEW YORK’S BATTERY PARK CITY, THIS SMALL SITE CONTINUES TO SPREAD ITS INFLUENCE—AND BRING PEOPLE JOY. BY JANE MARGOLIES / PHOTOGRAPHY BY LEXI VAN VALKENBURGH 102 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE JUNE 2016 LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE JUNE 2016 / 103 rom Mary Miss’s home and studio, it’s Today much of New York’s waterfront has been civic purpose—something she has continued to a couple blocks south, then west, to developed with attractive and popular parks and pursue with the nonprofit she founded, City as reach Battery Park City, the landmark public spaces like this one. But South Cove— Living Laboratory. residential and commercial develop- conceived at a time when the shoreline was a Fment built on landfill just off Lower Manhattan. no-man’s-land, cut off from the rest of the city “To work on something on this scale—something Miss, an artist, is a walker, and when her dog by roadways and railroad tracks, and dotted with permanent that would affect the lives of New Yorkers was young and spry, they used to make the trek derelict warehouses—helped spark New York’s —that was an amazing experience,” she says. together regularly, wending their way down to ABOVE rediscovery of its waterfront. It gave those who The landfill area— South Cove, the small park along the Hudson still mostly undeveloped lived and worked in Manhattan a toehold on The three of them had never worked together River she designed with the landscape architect when this photograph the river. -

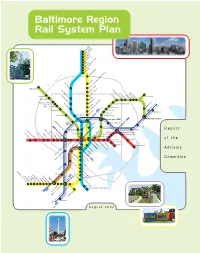

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

Salvation in a Grain of Sand O

SALVATIO N IN A GRAIN OF SAND RECKONING WITH THE OCEAN’S FURY CAME EARLY TO A FAMOUS HOUSE ON LONG ISLAND. BY MAC GRISWOLD N THE EAST END OF LONG ISLAND, O in the Hamptons, fabled or distinguished houses, including some by Norman Jaffe, the architect famed for using the area’s vernacu- lar language of potato barn and saltbox to create modernist masterpieces, are bulldozed at an ever increasing rate or disfigured by hair-raisingly inappropriate additions. Stephen and Sandy Perl- binder’s 1969 Jaffe house in Sagaponack is still standing after almost half a century but has been raised like a phoenix from disaster after disaster. In 1970, Architectural Record named it a “Record House,” igniting Jaffe’s career. Seen from the nearest road, now as then, its boxy profile stands distantly against a blank horizon. Beyond lies the Atlantic. The intervening 27 acres of cornfield, pond, meadow, and dunes are the inspired work of the landscape architect Christopher LaGuardia, ASLA, who has worked on this landscape since 1998, when two fierce winter nor’easters chewed out the then-legal beach bulkhead and the dune that the house originally stood on in less than 24 hours. In 2013, ASLA recognized LaGuardia’s work with the coveted Award of Excellence for residential design. SHANK ERIKA 96 / LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE SEP 2014 ERIKA SHANK ERIKA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE SEP 2014 / 97 Implicit in the award, and driving the appropri- the house to safety—the only possible move, given the circum- ateness of LaGuardia’s work in its Long Island stances, if the house wasn’t going to be torn down. -

Contents Introduction I Early Life 1 Coming to UC Santa Cruz As A

Contents Introduction i Early Life 1 Coming to UC Santa Cruz as a Student in 1967 5 Architecture School at Princeton University 17 Master’s Thesis on UCSC’s College Eight 24 Working as an Architect 29 Working as a Consultant for UC Santa Cruz 35 Becoming an Associate Architect at UC Santa Cruz 37 Bay Region Style 47 Learning the Job 49 Building a New Science Library 57 2 Other Early Architectural Projects at UC Santa Cruz 82 Cowell College Office Facility 82 Sinsheimer Labs 85 The Student Center 89 The Physical Education Facility 99 Colleges Nine and Ten 105 The Evolution of Planning at UC Santa Cruz 139 A History of Long Range Development Plans at UC Santa Cruz 143 The 1963 Long Range Development Plan 147 Long Range Development Plans in the 1970s 151 The 1988 Long Range Development Plan 152 The 2005 Long Range Development Plan 158 Campus Planning and the Overall Campus Structure 165 The Collaborative Relationship Between Physical Planning & Construction and Capital Planning 168 3 Building a Physical Planning & Construction Staff 170 Growth and Stewardship 174 More on the 2005 Long Range Development Plan 178 Strategic Futures Committee 182 Cooper, Robertson and Partners 187 The LRDP and the California Environmental Quality Act 198 The LRDP and Public Hearings 201 Enrollment Levels and the LRDP 203 Town-Gown Relations 212 The Dynamic Nature of Campus Planning 217 The LRDP Implementation Program 223 Design Advisory Board 229 Campus Physical Planning Advisory Committee 242 Working with the Office of the President 248 Different Kinds of Construction -

Wall Street's Wildest Scandals Sexy Spring

+PLUS Wall Street’s Wildest Scandals Sexy Spring Getaways Art Flash: Mogul Madness!? Meet NYC’s New Music & Film Ingénues Our Deluxe Design Hot List! & Manhattan’s Best Restaurants 10019 NY YORK, NEW FLOOR 8TH ST., 51ST W. 7 MANHATTAN M O D E R N L U X U RY.C O M MAR/APR 2010 $5.95 FEATURES CONTENTS CELEBRITY FEARLESS Julianne Moore talks middle FACTOR age, nudity and her new psychological thriller, Chloe . 62 FASHION NUDE Blushing (but not bashful) party AWAKENING dresses by Donna Karan New York, Valentino and Elie Saab bring the chic for spring. 66 THEORY OF is season, Gucci, Prada, DEVOLUTION Maison Martin Margiela and more break it down with deconstructed looks that rock! . .74 HOME BUILT TO LAST From new High Line condos to Andre Kikoski’s LED mania to a chair created to look like bone structure, a look at how design and architecture are coming together all over the city . .84 HOME WORKS e lives, likes and impossibly posh homes of Manhattanite designers Yoshiko Sato and Michael Morris of Morris Sato Studio and Kristina O’Neal, a founding principal at AvroKO, and her husband, developer Adam Gordon . 90 66 62 84 90 12 | | March/April 2010 | Visit Manhattan online at nyc.modernluxury.com. Home Works What’s every New Yorker’s dream? A spectacular home in the city for entertaining and a summer retreat for relaxing. Like these two | By William Bostwick and Melissa Feldman | Photography by Kate Glicksberg | Home | profile LORTISCILIT INIM POOLzzriustrud PARTY ming eu Afaccum guest/pool vullum house eraese withdionullamet, a garden sit, quis utilitynim iriureratum room below et, isconsenit situated venit, next cortin tovolesse a 20x40–foot quisim nos in-groundnonum volorper pool alisl plasteredipit ad minim in medium volum gray.venim A ilis freestanding num qu two-car garage is also included in the plan. -

March 10, 2016

March 10, 2016 DOWNTOWN COLUMBIA TAX INCREMENT FINANCING APPLICATION DATA PART I – APPLICATION FOR CREATION OF TAX INCREMENT FINANCE DISTRICT 1. Provide relevant information on the Applicant’s background and development experience. Applicant’s Response: Applicant, The Howard Research And Development Corporation, is the original petitioner for New Town Zoning and has been the developer of Columbia, Maryland, throughout its 50+ year history. Applicant is a wholly-owned subsidiary of The Howard Hughes Corporation (HHC), which is the Community Developer under the Downtown Columbia Plan and, through its other affiliates, is developing three other master planned communities in Las Vegas (Summerlin) and Houston (Bridgeland and The Woodlands) and mixed-use properties in 16 states from New York to Hawaii. John DeWolf is Senior Vice President Maryland, Development of HHC. Mr. DeWolf leads the Company’s strategic developments in Columbia, Maryland. Under Mr. DeWolf’s leadership, the Applicant’s affiliates developed the first new residential/retail mixed-use project in Downtown Columbia, The Metropolitan, with similar projects underway on an adjacent parcel, as well as the mixed use project in the newly renovated former Rouse Company Building with Whole Foods Markets and the Columbia Association’s Haven on the Lake; and has commenced renovations to make Merriweather Post Pavilion a state-of-the-art outdoor concert venue. Mr. DeWolf has over 30 years of real estate experience, including his work for New York & Company where he oversaw the addition of 225 stores. Mr. DeWolf has held senior positions with New England Development, Woolworth Corporation and The Disney Stores, Inc. Greg Fitchitt joined HHC as Vice President, Development, in March 2013, working on a variety of assets from Miami to California. -

GENERAL GROWTH PROPERTIES MOR October 2009 11-30-09 FINAL

UNITED STATES IlANKR UPTCY COURT CASE NO. 09-11977 (Jointly Admi nistered) Reporting Period: October 31, 2009 Federal Tax 1.0. # 42-1283895 CO RPO RATE MONTHLY OPERATI NG REP ORT FO R FILING ENTITIES ONLY I declare under penalties ofperjury (28 U.S.C. Sect ion 1746) that this repo rt and the attached documents are true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. GENERAL GROWTHPROPERTIES, INC. Date: November 30, 2009 Q GENERAL GROWTH PROPERTIES, INC. Combined Debtors Monthly Operating Report CASE NO. 09-11977 (Jointly Administered) Debtors Monthly Operating Report as of and for the Month Ended October 31, 2009 Index Combined Condensed Statements of Income and Comprehensive Income for the Month Ended October 31, 2009 and Cumulative Post-Petition Period Ended October 31, 2009.............................................................................................................. 3 Combined Condensed Balance Sheet............................................................................... 4 Notes to Unaudited Combined Condensed Financial Statements .................................... 5 Note 1: Chapter 11 Cases and Proceedings ........................................................... 5 Note 2: Basis of Presentation ................................................................................ 6 Note 3: Summary of Significant Accounting Policies .......................................... 7 Note 4: Cash and Cash Equivalents and Amounts Applicable to Debtor First-Lien Holders .................................................................................. -

Center Center

value from the CENTER PENNSYLVANIA REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT TRUST 2002 ANNUAL REPORT Financial Highlights (Thousands of dollars except per share amounts) Year Ended 12/31 2002 2001 2000 1999 1998 Funds from operations $ 51,167 $ 44,699 $ 45,844 $ 38,911 $ 34,576 Total real estate revenues 114,599 100,215 97,447 87,079 59,641 Investments in real estate, at cost 739,429 636,294 612,266 577,521 509,406 Net income 23,678 19,789 32,254 20,739 23,185 Net income per share 1.47 1.35 2.41 1.56 1.74 Distributions paid to shareholders/unitholders 37,492 36,478 28,775 27,562 26,485 Distributions paid per share 2.04 2.04 1.92 1.88 1.88 PENNSYLVANIA REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT TRUST (NYSE: PEI), FOUNDED IN 1960 AS ONE OF THE FIRST EQUITY REITS IN THE U.S., HAS A PRIMARY INVESTMENT FOCUS ON RETAIL MALLS AND POWER CENTERS LOCATED IN THE EASTERN UNITED STATES. FOLLOWING COMPLETION OF TRANSACTIONS ANNOUNCED IN MARCH 2003, THE COMPANY WILL BECOME THE LARGEST RETAIL OWNER/OPERATOR IN THE GREATER PHILADELPHIA METROPOLITAN AREA. THE COMPANY’S PORTFOLIO OF 32 PROPERTIES INCLUDES 14 SHOPPING MALLS AND 14 STRIP AND POWER CENTERS, TOTALLING 17.4 MILLION SQUARE FEET IN SEVEN STATES. PENNSYLVANIA REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT TRUST IS HEADQUARTERED IN PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA. PENNSYLVANIA REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT TRUST ı 2002 ANNUAL REPORT 1 dear fellow shareholders, AS THIS ANNUAL REPORT GOES TO PRESS, WE HAVE MADE ANNOUNCEMENTS THAT DRAMATICALLY STRENGHTEN our strategic focus on retail. We have agreed to purchase six shopping malls from The Rouse Company, making PREIT the largest retail owner/operator in the Greater Philadelphia metropolitan area upon completion of the transaction. -

Memo Regarding 250 Water Street

The South Street Seaport Historic District A National Treasure Worth Preserving Prepared by: The Seaport Coalition June 2020 Purpose This document was developed by the Seaport Coalition, an all-volunteer grass-roots community alliance with an interest in preserving the character of the South Street Historic District (the “District”) and its planned development. In further consideration of the Seaport Coalition’s Strategic Plan, the focus of this document is to provide an alternative perspective on the development plans of the Howard Hughes Corporation (“HHC”), a Texas-based developer, for 250 Water Street (the “Site”). The Seaport Coalition is working to ensure that the District maintains its historic character, and that the zoning limit is upheld. HHC has proposed various building plans for the Site. All of these plans contemplate a structure outside the zoning height restrictions of 120 feet. This document will outline a brief history of the South Street Seaport Historic District, a discussion around the history of 250 Water Street, a review of HHC’s financial condition, true plans and lobbying efforts, a brief history of the South Street Seaport Museum, and alternatives for future governance of the Historic District. We hope you come away better informed on this topic, with an appreciation of how much time and effort has been spent over the years to preserve the integrity and mission of the South Street Seaport Historic District. 2 Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 4 2 Importance of the Seaport 7 3 250 Water Street 18 4 HHC Implications