The Defensor Pacis of Marsiglio of Padua;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Authors of Articles in This Number of the Harvard Theological Review

THE AUTHORS OF ARTICLES IN THIS NUMBER OF THE HARVARD THEOLOGICAL REVIEW GEORGE HODGES, A.M., D.D., D.C.L., LL.D., Dean of the Episcopal Theological School, Cambridge. Author: The Episcopal Church; Christianity Between Sundays; The Heresy of Cain; In this Present World; Faith and Social Service; The Battles of Peace; The Path of Life; William Perm; Fountains Abbey; The Human Nature of the Saints; When the King Came; The Cross and Passion; Three Hundred Years of the Episcopal Church in America; The Administration of an Institutional Church; The Happy Family; The^ Pursuit of Happiness; The Year of Grace; Holderness; The Apprenticeship of Washington; The Garden of Eden; The Training qf Children in Religion; A Child's Guide to the Bible; Everyman's Relig- ion; Saints and Heroes; Class Book of Old Testament History; The Early Church; Henry Codman Potter, Seventh Bishop of New York; Religion in a World of War; How to Know the Bible. EPHRAIM EMERTON, Ph.D., Winn Professor of Ecclesiastical History, Emeritus, in Harvard University. Author: Introduction to the Study of the Middle Ages; Synopsis of the History of Continental Europe; Mediaeval Europe, 814-1300; Desid- erius Erasmus; Unitarian Thought; Beginnings of Modern Europe. JAMES BISSETT PRATT, A.M.,Ph.D., Professor of Philosophy in Williams College. Author: The Psychology of Religious Belief; What is Pragmatism? India and its Faith; Democracy and Peace. WILLIAM HALLOCK JOHNSON, Ph.D., D.D., Professor of Greek and New Testament Literature in Lincoln University, Chester County, Pennsylvania. Author: The Free-will Problem in Modem Thought; The Christian Faith under Modern Searchlights. -

Harvard Theological Review the Beginnings of Modern Europe

Harvard Theological Review http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR Additional services for Harvard Theological Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The Beginnings of Modern Europe (1250– 1458). Ephraim Emerton. Ginn & Co. 1918. Pp. xiv, 550. Maps. \$1.80. Dana C. Munro Harvard Theological Review / Volume 12 / Issue 02 / April 1919, pp 241 - 243 DOI: 10.1017/S0017816000010579, Published online: 03 November 2011 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/ abstract_S0017816000010579 How to cite this article: Dana C. Munro (1919). Review of Josiah Gilbert, and G. C. Churchill 'The Dolomite Mountains' Harvard Theological Review, 12, pp 241-243 doi:10.1017/S0017816000010579 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR, IP address: 128.122.253.228 on 25 Apr 2015 BOOK REVIEWS 241 religious crisis as more of an intellectual than of a mystical char- acter is entirely new and wholly original, but certainly it has never been propounded in such a definite way and so well harmonized with the whole of Augustine's intellectual and spiritual career, in a vigor- ous synthesis of his life and his theology. Being a work of synthesis, there is no room for details in the book. As for the synthesis itself, like all syntheses, it has a personal element, which, however, does not at all diminish the objective value of the study. G. F. LA PIANA. HARVARD UNIVEBSITY. THE BEGINNINGS OP MODERN EUROPE (1250-1458). EPHRAIM EMERTON. Ginn & Co. 1918. Pp. xiv, 550. Maps. $1.80. The publication of this new volume by Professor Emerton is an event of great interest to a host of his students and friends. -

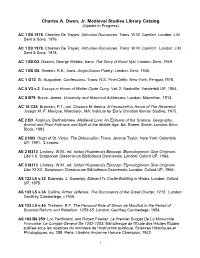

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy. -

38037732 Lese 1.Pdf

Archive for Reformation History An international journal concerned with the history of the Reformation and its significance in world affairs, published under the auspices of the Verein für Reformationsgeschichte and the Society for Reformation Research Board of Editors Jodi Bilinkoff, Greensboro/North Carolina – Gérald Chaix, Nantes – David Cressy, Columbus/Ohio – Michael Driedger, St. Catharines/Ontario – Mark Greengrass, Sheffield – Brad S. Gregory, Notre Dame/Indiana – Scott Hendrix, Princeton/New Jersey – Mack P. Holt, Fairfax/Virginia – Susan C. Karant-Nunn, Tucson/Arizona – Thomas Kaufmann, Göttingen – Ernst Koch, Leipzig – Ute Lotz-Heumann, Tucson/ Arizona – Janusz Małłek, Toruń – Silvana Seidel Menchi, Pisa – Bernd Moeller, Göttingen – Carla Rahn Phillips, Minneapolis/Minnesota – Heinz Scheible, Heidel- berg – Heinz Schilling, Berlin – Anne Jacobson Schutte, Charlottesville/Virginia – Christoph Strohm, Heidelberg – James D. Tracy, Minneapolis/Minnesota – Randall C. Zachman, Notre Dame/Indiana North American Managing Editors Brad S. Gregory – Randall C. Zachman European Managing Editor Ute Lotz-Heumann Vol. 104 · 2013 Gütersloher Verlagshaus Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte Internationale Zeitschrift zur Erforschung der Reformation und ihrer Weltwirkungen, herausgegeben im Auftrag des Vereins für Reformationsgeschichte und der Society for Reformation Research Herausgeber Jodi Bilinkoff, Greensboro/North Carolina – Gérald Chaix, Nantes – David Cressy, Columbus/Ohio – Michael Driedger, St. Catharines/Ontario – Mark Greengrass, Sheffield – Brad S. Gregory, Notre Dame/Indiana – Scott Hendrix, Princeton/New Jersey – Mack P. Holt, Fairfax/Virginia – Susan C. Karant-Nunn, Tucson/Arizona – Thomas Kaufmann, Göttingen – Ernst Koch, Leipzig – Ute Lotz-Heumann, Tucson/ Arizona – Janusz Małłek, Toruń – Silvana Seidel Menchi, Pisa – Bernd Moeller, Göttingen – Carla Rahn Phillips, Minneapolis/Minnesota – Heinz Scheible, Heidel- berg – Heinz Schilling, Berlin – Anne Jacobson Schutte, Charlottesville/Virginia – Christoph Strohm, Heidelberg – James D. -

Philip Melanchthon's Influence on the English Theological

PHILIP MELANCHTHON’S INFLUENCE ON ENGLISH THEOLOGICAL THOUGHT DURING THE EARLY ENGLISH REFORMATION By Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö A dissertation submitted In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology August 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö To the memory of my beloved husband, Tauno Pyykkö ii Abstract Philip Melanchthon’s Influence on English Theological Thought during the Early English Reformation By Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö This study addresses the theological contribution to the English Reformation of Martin Luther’s friend and associate, Philip Melanchthon. The research conveys Melanchthon’s mediating influence in disputes between Reformation churches, in particular between the German churches and King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1539. The political background to those events is presented in detail, so that Melanchthon’s place in this history can be better understood. This is not a study of Melanchthon’s overall theology. In this work, I have shown how the Saxons and the conservative and reform-minded English considered matters of conscience and adiaphora. I explore the German and English unification discussions throughout the negotiations delineated in this dissertation, and what they respectively believed about the Church’s authority over these matters during a tumultuous time in European history. The main focus of this work is adiaphora, or those human traditions and rites that are not necessary to salvation, as noted in Melanchthon’s Confessio Augustana of 1530, which was translated into English during the Anglo-Lutheran negotiations in 1536. Melanchthon concluded that only rituals divided the Roman Church and the Protestants. -

Church History April

Church History Catalog April 2013 Windows Booksellers 199 West 8th Ave., Suite 1 Eugene, OR 97401 USA Phone: (800) 779-1701 or (541) 485-0014 * Fax: (541) 465-9694 Email and Skype: [email protected] Website: http://www.windowsbooks.com Monday - Friday: 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM, Pacific time (phone & in-store); Saturday: Noon to 3:00 PM, Pacific time (in-store only- sorry, no phone). Our specialty is used and out-of-print academic books in the areas of theology, church history, biblical studies, and western philosophy. We operate an open shop and coffee house in downtown Eugene. Please stop by if you're ever in the area! When ordering, please reference our book number (shown in brackets at the end of each listing). Prepayment required of individuals. Credit cards: Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Discover; or check/money order in US dollars. Books will be reserved 10 days while awaiting payment. Purchase orders accepted for institutional orders. Shipping charge is based on estimated final weight of package, and calculated at the shipper's actual cost, plus $1.00 handling per package. We advise insuring orders of $100.00 or more. Insurance is available at 5% of the order's total, before shipping. Uninsured orders of $100.00 or more are sent at the customer's risk. Returns are accepted on the basis of inaccurate description. Please call before returning an item. __2000 Ans de Christianisme, Tome I__. Société d'Histoire Chrétienne. 1975. Hardcover, no dust jacket.. 288pp. Very good $10 [381061] . __2000 Ans de Christianisme, Tome II__. -

Gregory VII and the Investiture Controversy Samuel Dollarhide Western Oregon University, [email protected]

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2010 “In the Name of Almighty God” Gregory VII and the Investiture Controversy Samuel Dollarhide Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Dollarhide, Samuel, "“In the Name of Almighty God” Gregory VII and the Investiture Controversy" (2010). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 94. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/94 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Investiture Controversy was a conflict between Pope Gregory VII and the German King Henry IV over who had the right to appoint church officials in the Catholic Church. In the Roman Council of 1074 presided over by Gregory he declared: “Those who have been advanced to any grade of holy orders, or to any office, through simony, that is the payment of money, shall hereafter have no right to officiate in the holy church.”1 This statement as well as several others made throughout the Dictatus Papae2 offended and enraged secular rulers across Western Europe, especially Henry IV the Holy Roman Emperor, who previous to Gregory’s pontificate had appointed church officials at their pleasure. This was the escalation of a growing and serious rift between the Church in Rome and the secular power in the Holy Roman Empire. -

Church and Council: the Ecclesiology of Marsilius of Padua

ANTHONY C. YU Church and Council: The Ecclesiology of Marsilius of Padua With the recent convention and completion of the Second Vatican Council, one traditional concern of the Christian church once more has been placed in sharp focus. Within the context of reform, renewal, and ecumenical conversa tion, the question of church and council has been raised and discussed with fresh significance.1 It is not surprising today to find Roman Catholics and Protestants, though they may differ widely in their theological assumptions, all earnestly debating the possibilities of a church council for internal reform and for external reunion of the divided communions. In light of these develop ments, it is instructive to examine afresh some of the ideas of Marsilius of Padua, who, as a Roman Catholic historian has recently observed, has conventionally been regarded as one of the fathers of modem conciliar theory.2 Whether such an opinion is historically accurate remains a subject of controversy and research. However, there can be no denial of the fact that Marsilius' Defensor Pacis, as a document, was an important milestone in the whole history of conciliar theory and the conciliar movement, and it thus is a significant link from the fourteenth century down to the present. The purpose of the study is to examine and assess Marsilius' concept of the church, with special attention to his theory of the general council. Before we begin formal exposition of the Marsilian ecclesiology, a .word on historical background seems appropriate. When the ideas of the Paduan are studied as more or less isolated phenomena, they appear to be strikingly original and independent of tradition.8 Yet more recent research tends to minimize this emphasis, by placing Marsilius in the context of his contem porary society, intellectual and otherwise.4 A note on historical background 1. -

“Developments, Reforms, and Two Great Reformations: Towards a Historical Assessment of Vatican II”

Boston College -- Office of University Mission and Ministry “Developments, Reforms, and Two Great Reformations: Towards a Historical Assessment of Vatican II” BY JOHN W. O’MALLEY, S.J. Published in Theological Studies, vol. 44 (1983). ©1983 Theological Studies. Used with permission. We have just celebrated the twentieth anniversary of the start of Vatican Council II, and questions about its significance exercise us today as urgently as they did while the Council was in session.1 These questions are often addressed to historians. The familiar evasion that it is too soon to judge is not without merit, but it also risks relegating the historical profession to irrelevance for the contemporary life of the Church.2 It was for this reason that I attempted some years ago in the pages of this journal to venture an assessment of the Council, and I would now like to take up the subject again, but from a different point of view.3 The present article presupposes the earlier one and builds upon it. In that earlier article I stated: "In the breadth of its applications and in the depths of its implications, aggiornamento was a revolution in the history of the idea of reform."4 I still stand by that judgment. The question today, however, is not whether "the idea" of aggiornamento was revolutionary but whether the applications and implications of the idea are correspondingly being translated into action. Is a "revolution" taking place, or did Catholicism simply indulge in a momentary flirtation or infatuation with an idea? How much and how deeply have things changed? What kind of "reform" did the Council initiate, and how can its magnitude, or finitude, be assessed? These are the questions that seem to be on many people's minds. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Frontiers and borders : sources of transcendent credibility and the boundaries between political units Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/84b1t6kz Author Williamson, Rosco Publication Date 2007 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California i UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Frontiers and Borders: Sources of Transcendent Credibility and the Boundaries between Political Units A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Rosco Williamson Committee in charge: Professor David Mares, Chair Professor Alan Houston Professor Richard Madsen Professor Victor Magagna Professor Michael Monteon 2007 ii Copyright Rosco Williamson, 2007 All rights reserved iii The dissertation of Rosco Williamson is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2007 iii iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page...............................................................................................................iii Table -

The Murder of Charles the Good

The Murder of Charles the Good RECORDS OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION RECORDS OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION TbtArt of Courtly Love, bv Andreas Capellanus. Translated with an introduction and notes by John Jay Parry. The Correspondence of Pope Gregory HI: Selected Le Iters from the Registrum. Translated with an introduction by Ephraim Emerton. Medieval Handbooks of Penance: The Principal Libri Poenitentiales and Selections from Related Documents. Translated bv John T. McNeill and 1 lelena M. Gamer. Macrobius: Commentary on The Dream of Scipio. Translated with an introduction by William Harris Stahl. Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean IVorld: Illustrative Documents. Translated with introductions and notes by Robert S. Lopez and Irving W. Raymond, with a foreword and bibliography by Olivia Remie Constable. The Cosmographia ofBemardus Sihestris. Translated with an introduction by Winthrop Wetherbee. Heresies of the High Middle Ages. Translated and annotated by Walker L. Wakefield and Austin P. Evans. The Didascalicon of Hugh of Saint Victor: A Medieval Guide to the Arts. Translated with an intro- duction by Jerome Taylor. Martianus Capella and the Seven Libera! Arts. Vol. I: The Quadrivium of Martianus Capella: Latin Traditions in the Mathematical Sciences, by William Harris Stahl with Richard Johnson and E. L. Burge. Vol. II: The Marriage of Philology and Mercury, by Martianus Capella. Translated by William Harris Stahl and Richard Johnson with E. L.. Burge. The See of Peter, bv James T. Shotwell and Louise Ropes Loomis. Two Renaissance Book Hunters: The Letters oj'Poggius Bracciolini to Nicolaus df Niccolis. Translated and annotated by Phyllis Walter Goodhart (Jordan. Guillaume d'Orange: Four Twelfth-Century Epics. -

Marsilius of Padua: the Defender of the Peace Edited by Annabel Brett Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521789117 - Marsilius of Padua: The Defender of the Peace Edited by Annabel Brett Frontmatter More information MARSILIUS OF PADUA: THE DEFENDER OF THE PEACE The Defender of the Peace of Marsilius of Padua is a massively influential text in the history of western political thought. Marsilius offers a detailed analysis and explanation of human political communities, before going on to attack what he sees as the obstacles to peaceful human coexistence – principally the contemporary papacy. Annabel Brett’s authoritative rendition of the Defensor pacis is the first new translation in English for fifty years, and a major contribution to the series of Cambridge Texts: all of the usual series features are provided, including chronology, notes for further reading, and up-to-date annotation aimed at the student reader encountering this classic of medieval thought for the first time. This new edition of The Defender of the Peace is a scholarly and a pedagogic event of great importance, of interest to historians, political theorists, theologians and philosophers at all levels from second-year undergraduate upwards. The editor and translator ANNABEL BRETT is Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Gonville and Caius College. Her previous publications include Liberty, Right and Nature: Individual Rights in Later Scholastic Thought (Cambridge, 1997). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521789117 - Marsilius of Padua: The Defender of the Peace Edited by