Phil‟S Classical Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty Recital Piano Vs. Viola: a Romantic Duel Jasmin Arakawa, Piano Rudolf Haken, Five-String Viola ______

Faculty Recital Piano vs. Viola: A Romantic Duel Jasmin Arakawa, piano Rudolf Haken, five-string viola ________________________________ Sonata in E-flat Major, op. 120, no. 2 (1894) Johannes Brahms Allegro amabile (1833-1897) Allegro appassionato Andante con moto; Allegro Grandes études de Paganini (1851) Franz Liszt No. 5 (1811-1986) No. 2 No. 3 “La Campanella” Caprices (ca. 1810) Niccolò Paganini (1833-1897) No. 9 arranged by Rudolf Haken No. 17 “La Campanella” from Violin Concerto No.2 (1826) INTERMISSION Concerto in F (2014) Rudolf Haken Possum Trot (b. 1965) Triathlon Hoedown Walpurgisnacht Le Grand Tango (1982) Ástor Piazzolla (1921-1992) ________________________________ The Fourth Concert of Academic Year 2014-2015 Tuesday, September 16, 2014 7:30 p.m. A charismatic and versatile pianist, Jasmin Arakawa has performed widely in North America, Central and South America, Europe, and Japan. Described by critics as a “lyrical” pianist with “impeccable technique” (The Record), she has been heard in prestigious venues worldwide including Carnegie Hall, Salle Gaveau (Paris) and Victoria Hall (Geneva). She has appeared as a concerto soloist with the Philips Symphony Orchestra in Amsterdam, and with the Piracicaba Symphony Orchestra in Brazil. Arakawa’s interest in Spanish repertoire grew out of a series of lessons with Alicia de Larrocha in 2004. She has subsequently recorded solo and chamber pieces by Spanish and Latin American composers (LAMC Record), under the sponsorship of the Spanish Embassy as a prizewinner at the Latin American Music Competition. An avid chamber musician, she has collaborated with such artists as cellists Colin Carr and Gary Hoffman, flutists Jean Ferrandis and Marina Piccinini, clarinetist James Campbell, and the Penderecki Quartet. -

The Form of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites Daniel E. Prindle University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Composition Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Prindle, Daniel E., "The orF m of the Preludes to Bach's Unaccompanied Cello Suites" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 636. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/636 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2011 Master of Music in Music Theory © Copyright by Daniel E. Prindle 2011 All Rights Reserved ii THE FORM OF THE PRELUDES TO BACH’S UNACCOMPANIED CELLO SUITES A Thesis Presented by DANIEL E. PRINDLE Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Gary Karpinski, Chair _____________________________________ Miriam Whaples, Member _____________________________________ Brent Auerbach, Member ___________________________________ Jeffrey Cox, Department Head Department of Music and Dance iii DEDICATION To Michelle and Rhys. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the generous sacrifice made by my family. -

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

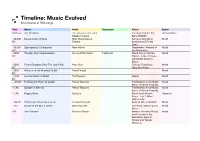

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

Maud Powell As an Advocate for Violinists, Women, and American Music Catherine C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 "The Solution Lies with the American Women": Maud Powell as an Advocate for Violinists, Women, and American Music Catherine C. Williams Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC “THE SOLUTION LIES WITH THE AMERICAN WOMEN”: MAUD POWELL AS AN ADVOCATE FOR VIOLINISTS, WOMEN, AND AMERICAN MUSIC By CATHERINE C. WILLIAMS A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Catherine C. Williams defended this thesis on May 9th, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Thesis Michael Broyles Committee Member Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Maud iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents and my brother, Mary Ann, Geoff, and Grant, for their unceasing support and endless love. My entire family deserves recognition, for giving encouragement, assistance, and comic relief when I needed it most. I am in great debt to Tristan, who provided comfort, strength, physics references, and a bottomless coffee mug. I would be remiss to exclude my colleagues in the musicology program here at The Florida State University. The environment we have created is incomparable. To Matt DelCiampo, Lindsey Macchiarella, and Heather Paudler: thank you for your reassurance, understanding, and great friendship. -

Newsletter 1

The instruments of choice for the best players in the world... MARK WOOD MARK WOOD, award winning composer, interna- Magazine, among others. tional recording artist, and electric violinist, is widely Mark is currently starring in a national TV ad campaign acknowledged as the premier electric rock violinist of for Pepsi. The music track is a Kanye West produced his generation. Mark studied under maestro Leonard hip hop version of “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” Bernstein at Tanglewood and attended the Juilliard (featuring the rapper Nas). School of Music on full scholarship, which he left Mark won an Emmy award for his music for the Tour to pursue his vision of bringing rock violin into the De France bike race on CBS-TV and received three mainstream. His first release “Voodoo Violince” is widely additional Emmy nominations. As an inventor, Mark hailed as the quintessential rock violin record. In addi- established Wood Violins, a company whose mission is tion to his own band, The Mark Wood Experience, he to make Mark’s incredible instruments available to the has received two platinum and gold records from his general public. work with Trans-Siberian Orchestra, and has toured Mark’s Electrify Your Strings!™ series of music educa- and performed with Dee Snider’s Van Helsing’s tion programs have become enormously successful Curse, Celine Dion, Billy Joel, Lenny Kravitz, and and in demand with hundreds of schools participating Jewel. Mark has been a featured guest on The Tonight around the country. Show with Jay Leno, and has had articles written His definitive electric violin method book by the about him in the New York Times, USA Today, and Time same name is a must-have for all string players. -

Cymbal Playing Robot by Godfried-Willem Raes

<Synchrochord> The first bowed instrument robot we designed was <Hurdy>, an automated hurdy gurdy, built between 2004 and 2007. The building of that robot had many problems and our attempts to solve these have lead to many new ideas and experiments regarding acoustic sound production from bowed strings. Between 2008 and 2010 we worked very hard on our <Aeio> robot, where we used only two phase electromagnetic excitation of the twelve strings. Although <Aeio> works pretty well, it can not serve as a realistic replacement of the cello as we first envisaged it. The pretty slow build-up of sound was the main problem. The cause being the problematic coupling of the magnetic field to the string material. Thus we went on experimenting with bowing mechanisms until we discovered that it is possible to excite the string mechanically synchronous with the frequency to which it is tuned. For such an approach to work well, we need a very precize synchronous motor with a very high speed. Change of speed ought to be very fast, thus necessitating a low inertia motor as well as a fast braking mechanism. Needless to say, but the motor should also run as quietly as possible. To relax the high speed requirement a bit, we designed a wheel mounted on the motor axis with ten plectrums around the circumference. Thus for every single rotation of the spindle, the string will be plucked ten times. Follows that in order to excite a string tuned to 880Hz, we need a rotational frequency of 88Hz. Or, stated in rotations per minute: 5280 rpm. -

Complete Piano Music Rˇák

DVO COMPLETE PIANO MUSIC RˇÁK Inna Poroshina piano QUINTESSENCE · QUINTESSENZ · QUINTESSENZA · QUINAESENCIA · QUINTESSÊNCIA · QUINTESSENCE · QUINTESSENZ · QUINTESSENZA · QUINAESENCIA · QUINTESSÊNCIA Antonín Dvorˇák 1841-1904 Complete Piano Music Theme and Variations Op.36 (1876) Two Furiants Op.42 (1878) Six Mazurkas Op.56 1. Theme 1’21 26. No.1 in D major 5’33 51. No.1 2’50 76. No.4 in D minor, poco andante 2’46 2. Variation 1 1’09 27. No.2 in F major 7’38 52. No.2 2’28 77. No.5 in A minor, vivace 3’04 3. Variation 2 1’12 53. No.3 1’58 78. No.6 in B major, poco allegretto 2’56 4. Variation 3 2’56 Eight Waltzes Op.54 (1880) 54. No.4 2’57 79. No.7 in G flat major, poco lento 5. Variation 4 0’41 28. No.1 in A major 3’39 55. No.5 2’37 e grazioso 3’26 6. Variation 5 1’00 29. No.2 in A minor 4’05 56. No.6 2’35 80. No.8 in B minor, poco andante 3’22 7. Variation 6 1’36 30. No.3 in C sharp minor 2’55 8. Variation 7 0’58 31. No.4 in D flat major 2’52 57. Moderato in A major B.116 2’10 81. Dumka, Op.12/1 (1884) 4’00 9. Variation 8 3’53 32. No.5 in B flat major 3’00 33. No.6 in F major 5’05 58. Question, B.128a 0’27 82. -

Violin Concerto in D Major Composed in 1931 Igor

VIOLIN CONCERTO IN D MAJOR COMPOSED IN 1931 IGOR STRAVINSKY BORN IN LOMONOSOV, RUSSIA, JUNE 17, 1882 DIED IN NEW YORK CITY, APRIL 6, 1971 Some of the most famous violin concertos, such as those by Mozart, were written by composers who played the instrument and who possessed first-hand knowledge of its potential. Concertos by a virtuoso violinist like Paganini show even greater evidence of knowing the best ways to exploit the fiddle to full effect, even if the profundity of the compositions themselves do not match the brilliance of the technical virtuosity they exhibit. And then there are those composers who rely on the kindness of others, sometimes strangers, calling upon them to help mold their musical ideas into idiomatic string writing. Joseph Joachim provided just such wise counsel for Brahms, Dvořák, Bruch, and other 19th-century masters, so much so that at times he approached becoming co-composer. One of the most fruitful partnerships to emerge in the 20th century was between Igor Stravinsky and the Polish-American violinist Samuel Dushkin (1891-1976). The result of their first collaboration in 1931 was the celebrated Concerto we hear performed tonight, a work that initiated a 40-year friendship, lasting until the composer’s death, and that resulted in other compositions, transcriptions, and numerous performances together. “A CLOSE FRIENDSHIP” By 1930 Stravinsky had already written a number of concertos, all of them keyboard works intended for his own use in concert. When the music publisher Willy Strecker approached him with a commission for Dushkin, Stravinsky was initially skeptical. He had never met Dushkin, nor heard him play. -

PROGRAM NOTES Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Johann Sebastian Bach Born March 21, 1685, Eisenach, Thuringia, Germany. Died July 28, 1750, Leipzig, Germany. Orchestral Suite No. 1 in C Major, BWV 1066 The dating of Bach’s four orche stral suites is uncertain. The first and fourth are the earliest, both composed around 1725. Suite no. 1 calls for two oboes and bassoon, with strings and continuo . Performance time is approximately twenty -one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s fir st subscription concert performances of Bach’s First Orchestral Suite were given at Orchestra Hall on February 22 and 23, 1951, with Rafael Kubelík conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on May 15, 16, and 17, 2003, with D aniel Barenboim conducting. Today it’s hard to imagine a time when Bach’s name meant little to music lovers, and when his four orchestral suites weren’t considered landmarks. But in the years immediately following Bach’s death in 1750, public knowledge o f his music was nil, even though other, more cosmopolitan composers, such as Handel, who died only nine years later, remained popular. It’s Mendelssohn who gets the credit for the rediscovery of Bach’s music, launched in 1829 by his revival of the Saint Ma tthew Passion in Berlin. A great deal of Bach’s music survives, but incredibly, there’s much more that didn’t. Christoph Wolff, today’s finest Bach biographer, speculates that over two hundred compositions from the Weimar years are lost, and that just 15 to 20 percent of Bach’s output from his subsequent time in Cöthen has survived. -

Rachel Barton Pine

Rachel Barton Pine Heralded as a leading interpreter of the great classical masterworks, international concert violinist Rachel Barton Pine thrills audiences with her dazzling technique, lustrous tone and emotional honesty. With an infectious joy in music-making and a passion for connecting historical research to performance, Pine transforms audiences’ experiences of classical music. During the 2015-16 season, Pine will perform concertos by Beethoven, Brahms, Bruch, Dvorak, Fairouz, Mozart, Sibelius and Vivaldi, with orchestras including the Santa Rosa Symphony, the New Mexico Philharmonic, and the Flagstaff, Windsor, and Gainesville Symphony Orchestras. She will continue her recital tour of the Six Bach Sonatas and Partitas for Unaccompanied Violin in Gainesville, FL and Washington, D.C. In April, 2016 Avie Records will release Pine’s performance of J.S. Bach’s Six Sonatas and Partitas for Violin. Pine recently celebrated the release of her debut album on Avie: Mozart: Complete Violin Concerto, Sinfonia Concertante, with conductor Sir Neville Marriner and The Academy of St Martin in the Fields. In September 2015 Cedille Records releases her recording of Vivaldi: The Complete Viola D’Amore Concertos with Ars Antigua. This season a high-definition, life size video of Pine playing and being interviewed will be the culminating installation of “Stradivarius: Origins and Legacy of the Greatest Violin Maker,” a new exhibit of treasures made by master violin makers including Andrea Amati, Guarneri del Gesù, and Antonio Stradivari debuting at the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix, AZ. Pine has appeared as soloist with many of the world’s most prestigious ensembles, including the Chicago Symphony; the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Royal Philharmonic; and the Netherlands Radio Kamer Filharmonie. -

Fomrhi Quarterly

Quarterly No. Ill, February 2009 FoMRHI Quarterly BULLETIN 111 Christopher Goodwin 2 COMMUNICATIONS 1835 Jan Steenbergen and his oboes Jan Bouterse 5 1836 Observations on glue and an early lute construction technique John Downing 16 1837 Thomas Stanesby Junior's 'True Concert Flute' Philippe Bolton 19 1838 Oil paintings of musical instruments - should we trust the Old Masters? Julian Goodacre 23 1839 A method of fixing loose soundbars Peter Bavington 24 1840 Mediaeval and Renaissance multiple tempo standards Ephraim Segerman 27 1841 The earliest soundposts Ephraim Segerman 36 1842 The historical basis of the modern early-music pitch standard ofa'=415Hz Ephraim Segerman 37 1843 Notes on the symphony Ephraim Segerman 41 1844 Some design considerations in making flattened lute backs Ephraim Segerman 45 1845 Tromba Marina notes Ian Allan 47 1846 Woodwinds dictionary online Mona Lemmel 54 1847 For information: Diderot et d'Alembert, L'Encyclopedie - free! John Downing 55 1848 'Mortua dolce cano' - a question John Downing 56 1849 Mortua dolce cano - two more instances Chris Goodwin 57 1850 Further to Comm. 1818, the new Mary Rose fiddle bow Jeremy Montagu 58 1851 Oud or lute? Comm. 1819 continued John Downing 59 1852 Wood fit for a king - a case of mistaken identity? Comm 1826 updated John Downing 62 1853 Reply to Segerman's Comm. 1830 John Downing 64 1854 Reply to John Catch's Comm 1827 on frets and temperaments Thomas Munck 65 1856 Re: Comms 1810 and 1815, Angled Bridges, Tapered Strings Frets and Bars Ephraim Segerman 66 1857 The lute in renaissance Spain: comment on Comm 1833 Ander Arroitajauregi 67 1858 Review of Modern Clavichord Studies: De Clavicordio VIII John Weston 68 The next issue, Quarterly 112, will appear in May 2009.