Blessed Cecilia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

That to See How Britten Handles the Dramatic and Musical Materials In

BOOKS 131 that to see how Britten handles the dramatic and musical materials in the op- era is "to discover anew how from private pain the great artist can fashion some- thing that transcends his own individual experience and touches all humanity." Given the audience to which it is directed, the book succeeds superbly. Much of it is challenging and stimulating intellectually, while avoiding exces- sive weightiness, and at the same time, it is entertaining in the very best sense of the word. Its format being what it is, there are inevitable duplications of information, and I personally found the Garbutt and Garvie articles less com- pelling than the remainder of the book. The last two articles of Brett's, excel- lent as they are, also tend to be a little discursive, but these are minor reserva- tions. For anyone who cares for this masterwork of twentieth-century opera, Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/4/3/131/1587210 by guest on 01 October 2021 or for Britten and his music, this book is obligatory reading. Carlisle Floyd Peter Grimes/Gloriana Benjamin Britten English National Opera/Royal Opera Guide 24 Nicholas John, series editor London: John Calder; New York: Riverrun Press, 1983 128 pages, $5.95 (paper) The English National Opera/Royal Opera Guides, small paperbacks with siz- able contents, are among the best introductions available to the thirty-plus operas published in the series so far. Each guide includes some essays by ac- knowledged authorities on various aspects of its subject, followed by a table of major musical themes, a complete libretto (original language plus transla- tion), a brief bibliography, and a discography. -

JOAN SUTHERLAND John Pritchard (1918–89)

JOAN SUTHERLAND John Pritchard (1918–89). Walthamstow-born, John Pritchard learned his craft as principal conductor of the Derby String Orchestra, before joining the music staff of Glyndebourne in 1947. Appointed Chorus Master in 1949, he was soon sharing major Mozart productions with Fritz Busch, conducting the London Philharmonic Orchestra there and swiftly expanding his repertoire. The company’s Musical Director from 1969 to 1977, he was also a regular guest at the Royal Opera, where in 1955 he conducted the premiere of Tippett’s A Midsummer Marriage. His opera and concert work encircled the globe, with periods at the helm of many companies and orchestras, notably the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and BBC Symphony. He was knighted in 1983. Though his full diary could result in perfunctory routine, fiery theatricality and a grasp of essentials inform his best work – not least in many studio and off-air recordings made with his ‘home’, Glyndebourne company, and for BBC radio. Joan Sutherland (1926–2010). The world-renowned soprano Joan Sutherland left her Sydney home for London in 1952, with the ultimate aim of singing Wagner. Contracted to Covent Garden, she felt her future lay in heavy, dramatic roles; and her early assignments there included Amelia in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera and the title role in Aida. Soon her breathtaking agility, crystalline staccatos and unique stratospheric purity became evident – not least as Jenifer in Tippett’s The Midsummer Marriage, followed swiftly by the doll Olympia in Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann (both 1955). Although increasingly identified with the bel canto repertoire, until her 1959 Covent Garden triumph in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor she kept her options open. -

Concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra for Seasons 1946-47 to 2006-07 Last Updated April 2007

Artistic Director NEVILLE CREED President SIR ROGER NORRINGTON Patron HRH PRINCESS ALEXANDRA Concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra For Seasons 1946-47 To 2006-07 Last updated April 2007 From 1946-47 until April 1951, unless stated otherwise, all concerts were given in the Royal Albert Hall. From May 1951 onwards, unless stated otherwise, all concerts were given in The Royal Festival Hall. 1946-47 May 15 Victor De Sabata, The London Philharmonic Orchestra (First Appearance), Isobel Baillie, Eugenia Zareska, Parry Jones, Harold Williams, Beethoven: Symphony 8 ; Symphony 9 (Choral) May 29 Karl Rankl, Members Of The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Kirsten Flagstad, Joan Cross, Norman Walker Wagner: The Valkyrie Act 3 - Complete; Funeral March And Closing Scene - Gotterdammerung 1947-48 October 12 (Royal Opera House) Ernest Ansermet, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Clara Haskil Haydn: Symphony 92 (Oxford); Mozart: Piano Concerto 9; Vaughan Williams: Fantasia On A Theme Of Thomas Tallis; Stravinsky: Symphony Of Psalms November 13 Bruno Walter, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Isobel Baillie, Kathleen Ferrier, Heddle Nash, William Parsons Bruckner: Te Deum; Beethoven: Symphony 9 (Choral) December 11 Frederic Jackson, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Ceinwen Rowlands, Mary Jarred, Henry Wendon, William Parsons, Handel: Messiah Jackson Conducted Messiah Annually From 1947 To 1964. His Other Performances Have Been Omitted. February 5 Sir Adrian Boult, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Joan Hammond, Mary Chafer, Eugenia Zareska, -

The Turn of the Screw Onadek Winan As Aricie in Juilliard Opera's Production of Rameau's Hippolyte Et Aricie

BENJAMIN BRITTEN The Turn of the Screw Onadek Winan as Aricie in Juilliard Opera's production of Rameau's Hippolyte et Aricie A Message from Brian Zeger We choose the operas that make up the Juilliard opera season for a number of reasons. They need to be great works that will nourish the growth of our students and satisfy the tastes of a sophisticated public. They need to complement one another so that students and audiences receive a varied diet. As it happens, all three of the works we’re presenting this season—Britten’s The Turn of the Screw, Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and Mozart’s Don Giovanni—seem to speak to the current moment of upheaval in gender and sexual politics. Whether this is chance or the mysterious working of the zeitgeist, I welcome the opportunity to reflect on these timeless issues through the lenses of gifted composers and librettists. The first genius behindThe Turn of the Screw is Henry James, whose 1898 novella is a tour-de-force of ambiguity, indirectness, and horror. Librettist Myfanwy Piper has adroitly transformed the suggestiveness of James’ prose into dialogue that hides as much as it discloses. Rather than a conventional orchestra, Britten’s masterly score employs only solo instruments, demanding that each player bring a soloist’s range of color and imagination. The result is a haunting and highly dramatic piece with virtuoso challenges for the whole cast as well as all the orchestral players. Britten refuses to reduce the story to a simple dichotomy of innocence and corruption. -

Peter Grimes BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913 – 1976)

Peter Grimes BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913 – 1976) coc.ca/Explore Table of Contents Welcome .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Opera 101 ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Attending the Opera ................................................................................................................................... 5 Characters and Synopsis .......................................................................................................................... 7 Genesis of the Opera .................................................................................................................................. 9 Listening Guide ............................................................................................................................................ 12 What to Look for .......................................................................................................................................... 16 COC Spotlight: Alan Moffat .................................................................................................................... 18 Active Learning ............................................................................................................................................ 20 Bibliography .................................................................................................................................................. -

TEM Issue 7 Cover and Back Matter

FOLK SONG ARRANGEMENTS by The BENJAMIN BRITTEN These three volumes of folk song arrangements, the first of which appeared in 1943, have established ENGUSH OPERA GROUP themselves through their many performances in the concert hall and by means of broadcast and record- Chairman : The Rt. Hon. Oliver Lyttelton, D.S.O., M.C., M.P. ings, as one of the most successful series of songs Artistic Directors : in recent years. Mr. Britten has kept simplicity Benjamin Britten, Eric Crozier, John Piper in both the melodic line and its accompaniment. VOLUME I " BRITISH ISLES' High Voice 6/3 " The Sally Gardens "—" Little Sir William "—" The Bonny Earl o' Moray "—" O Can Ye Sew Cushions ? "— THE BEGGAR'S OPERA " The Trees They Grow So High "—" The Ash Grove " —" Oliver Cromwell." By JOHN GAY VOLUME II Music realised by "FRANCE High or Medium Voice 9/6 BENJAMIN BRITTEN " La Noel passee ' (Th. e Orpha. n and Kin_g Henry)— " Voici le Printemps " (Hear th' e "Voic' ' e of Spring)* ' — from the original airs " Fileuse " (When I was Young)—" Le roi s'en va-t'en chasse " (The King is gone a-hunting)—" La belle est au jardin d'amour " (Beauty in love's garden)—"II est Produced by Designed by quelqu'un sur terre " (There's someone in my fancy)— " Eho ! Eho ! "—" Quand j'etais chez mon pere " TYRONE GUTHRIE TANYA MOISEIWITCH (Heigh ho, heigh hi !) Cambridge Arts Theatre... ... May 24th VOLUME III " BRITISH ISLES High Voice 6/3 The Holland Festival ... ... June 25th "The Plough Boy"—"There's None to Soothe"— The Cheltenham Festival .. -

Albert Herring Benjamin Britten

NI 5824/6 In 1938 Knud Hegermann-Lindencrone suggested to the Royal Theatre that they should establish a National Vocal Archive, but because of the war this never happened. In Albert Herring 1948 the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen celebrated its bicentenary with eighteen special performances. It was Knud Hegermann-Lindencrone’s idea to acquire an American tape recorder and record all these performances. So it was that the fi rst tape-recorders Benjamin Britten arrived in Denmark, a Soundmirror BK-401 from the Brush Development Corporation English Opera Group closely followed by a machine from Magnecord Inc. The tapes arrived by plane from the manufacturer, 3M in Minnesota, only a few hours before the opening of the fi rst conducted by the composer performance. The American machine was designed for 60 Hz alternating current but Hegermann-Lindencrone modifi ed it to function on 50 Hz. Playing the oldest tapes today Recorded live at the on ordinary equipment will give the result that they are running 16.66 % too fast! Royal Theatre, Copenhagen Following the jubilee celebrations Hegermann-Lindencrone persuaded the Theatre September 1949 and the Company of actors, dancers and singers to permit him to record prominent productions, particularly premieres and international guest performers. Over the next forty years approximately 1500 performances were recorded. Hegermann-Lindencrone had a permanent installation for his recording equipment and microphones in the Theatre. He kept pace with technical developments, with a major change to stereo in 1958, and employed a sound engineer (Villy Bak) to do the actual recording. Hegermann- Lindencrone sold his collection to the Royal Theatre in 1989 where it is securely kept today together with backup copies undertaken in the 1990s. -

Opera Mcgill – Lisl Wirth Black Box Festival November 21, 22, 23 and 24, 2007 Pollack Hall

Schulich School of Music of McGill University Concerts and Publicity 555 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, Quebec H3A 1E3 Phone: (514) 398-5530 Fax: (514) 398-5514 PRESS RELEASE Opera McGill – Lisl Wirth Black Box festival November 21, 22, 23 and 24, 2007 Pollack Hall Albert Herring Benjamin Britten For immediate release November 19, 2007 – Opera McGill opens its 2007-2008 with Albert Herring by Benjamin Britten on November 21, 22, 23 and 24, at 7:30 p.m. in Pollack Hall for its Lisl Wirth Black Box Festival. Tickets for this production are $10 ($5 seniors and students) and are available at the Pollack Hall Box Office, Monday through Friday, 12:00 (noon) to 6:00 p.m., (514) 398-4547. With this production Opera McGill welcomes its new director, Patrick John Hansen, who will stage direct the cast of 13 students, including 3 children. From the orchestra pit, Julian Wachner, Opera McGill’s principal conductor, will conduct the singers and the small ensemble of 13 musicians as indicated by the composer. Comic opera in three acts, Op. 39, by Benjamin Britten to a libretto by Eric Crozier, after Guy de Maupassant’s short story Le rosier de Madame Husson, Albert Herring has been premiered on June 20, 1947 at Glyndebourne by the English Opera Group, an independent and progressive opera company launched by Britten and Crozier, with Peter Pears in the title role and Joan Cross as Lady Billow. “There are a number of themes being played out in this delightful libretto: Victorian fixation on morality, the British pre-occupation with correctness, judging persons strictly on their appearances, sexual repression (or lack thereof) in the countryside of Suffolk in 1900, and how to sever the apron string’s of not only a mother figure but society’s strings as well… Albert Herring is an opera that continues to amuse audience from production to production because of its terrific libretto and Britten’s magnificent genius of a score. -

Benjamin Britten World Premiere: 24 May 1948 Arts Theatre, Cambridge, United Kingdom Tyrone Guthrie, Director; English Opera Group Conductor: Benjamin Britten

9790060096877 Study Score (hardback) - Hawkes Pocket Score 1276 Benjamin Britten World Premiere: 24 May 1948 Arts Theatre, Cambridge, United Kingdom Tyrone Guthrie, director; English Opera Group Conductor: Benjamin Britten Billy Budd (original 4-Act version) op. 50 1951 2 hr 42 min Opera in four acts Major roles: T,Bar,B; minor roles: 4T,7Bar,BBar,2B; Benjamin Britten photo © Angus McBean children's roles: 4Tr,boy speaker,boy actors; men's chorus 4(II,III,IV=picc).2.corA.3(II=Ebcl,bcl;III=bcl).asax.2.dbn- 4.4(III in D).3.1-timp(3).perc(6):xyl/glsp/tgl/wdbl/tamb/SD/TD/BD/ OPERAS whip/cyms/small gong/4drums(on-stage)-harp-strings World Premiere: 01 Dec 1951 Albert Herring op. 39 Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, United Kingdom 1947 2 hr 17 min Basil Coleman, director; Royal Opera Covent Garden Conductor: Benjamin Britten Comic opera in three acts Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world 2S,2M,A,2T,2Bar,B; Children's roles:Tr,2S 1(=picc,afl).1.1(=bcl).1-1.0.0.0-perc(1):timp/SD/TD/BD/tgl/cyms/cast/ tamb/gong/bells/glsp/whip/wdbl-harp-pft(=conductor)- Billy Budd (reduced orchestration of 2-act version) strings(1.1.1.1.1) Benjamin Britten, arranged by Steuart Bedford 9790202519301 Libretto (German) 1951, rev.1960, orch. 2016 2 hr 38 min Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world 9790060013881 Libretto reduced orchestration of 2-act version 9790060013867 (Vocal Score) Major roles: T,Bar,B; minor roles: 4T,7Bar,BBar,2B; 9790060013850 Study Score (hardback) - Hawkes Pocket Score 854 children's roles: 4Tr,boy speaker,boy actors; men's chorus World Premiere: 20 Jun 1947 2(I&II=picc).2.corA.2(II=ebcl,bcl).2.dbn-4.3.3.1-timp(3).perc(6):xyl/glsp/tri/bl/tamb/SD/T Glyndebourne, United Kingdom D/BD/whip/cym/small gong/4dr/ Frederick Ashton, director; English Opera Group Conductor: Benjamin Britten World premiere of version: 01 Jul 2017 Indianola, Iowa, United States The Beggar's Opera op. -

Theatre Archive Project: Interview with Leo Kersley

THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT http://sounds.bl.uk Leo Kersley – interview transcript Interviewer: Thomas Dymond 17 July 2006 Dancer and Choreographer. Frederick Ashton; Lilian Baylis; Benjamin Britten; The Cherry Orchard; Joan Cross; Sid Field; Margot Fonteyn; John Gielgud; Robert Helpmann; Vivien Leigh; Music Hall; Nadia Nerina; Laurence Olivier; Ballet Rambert; Maria Rambert; Sadlers Wells Ballet; Antony Tudor; Ninette de Valois; Ralph Vaughan Williams's works. TD: Firstly, if you want to tell me about your career in general. You were a dancer, I believe, weren’t you, about how you came to be a dancer and you're initial experiences and anything you’d like to share. LK: Well, that’s pre-1945 [laughter] but Lilian Baylis said, just out of thin air when she introduced me to Queen Mary on the 22 December 1932, ‘Oh, and he’s going to join our ballet one day…’! I was flabbergasted! But if Miss Baylis said anything, it was so, so I thought, ‘Oh well, I’ll join their ballet’. And at this point Queen Mary, who I was chatting to, said, ‘Oh, if you’re going to do ballet, you must shake my hand…’, She drew herself up and put her hand out and shook, ‘…because I'm a pupil of the greatest dancer that ever lived: Marie Taglioni’. So, I thought that was lovely and she turned to go away, and then suddenly she turned back and said, ‘And that’s why I don’t have to wear a corset.’ [laughter] So, it was ordained by Baylis that I should be a ballet dancer, so I became one. -

Peter Grimes

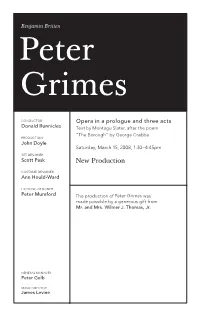

Benjamin Britten Peter Grimes CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and three acts Donald Runnicles Text by Montagu Slater, after the poem “The Borough” by George Crabbe PRODUCTION John Doyle Saturday, March 15, 2008, 1:30–4:45pm SET DESIGNER Scott Pask New Production COSTUME DESIGNER Ann Hould-Ward LIGHTING DESIGNER Peter Mumford The production of Peter Grimes was made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2007-08 Season The 69th Metropolitan Opera performance of Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes This performance is broadcast live over Conductor Donald Runnicles The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera International IN ORDER OF VOCAL APPEARANCE Radio Network, Hobson Two nieces sponsored by Dean Peterson Leah Partridge Toll Brothers, Erin Morley America’s luxury Swallow ® home builder , John Del Carlo Ned Keene with generous Teddy Tahu Rhodes long-term Peter Grimes support from Anthony Dean Griffey The Annenberg Mrs. Sedley Boy Foundation Felicity Palmer Logan William Erickson and the Vincent A. Stabile Ellen Orford Villagers Endowment for Patricia Racette Roger Andrews, David , Asch, Kenneth Floyd, Broadcast Media Auntie and through David Frye, Jason Jill Grove contributions from Hendrix, Mary Hughes, listeners worldwide. Bob Boles Robert Maher, Timothy Greg Fedderly Breese Miller, Jeffrey This afternoon’s Mosher, Richard Pearson, performance is also Captain Balstrode Mark Persing, Mitchell being broadcast Anthony Michaels-Moore Sendrowitz, Daniel live on Metropolitan Clark Smith, Lynn Taylor, Opera Radio, on Rev. Horace Adams Joseph Turi Sirius Satellite Radio Bernard Fitch channel 85. Saturday, March 15, 2008, 1:30–4:45pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

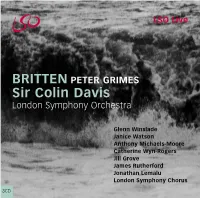

BRITTEN PETER GRIMES Sir Colin Davis

LSO Live LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional LSO Live témoigne de LSO Live fängt unter performances from the concerts d’exception, donnés Einsatz der neuesten High- finest musicians using the par les musiciens les plus Density-Aufnahmetechnik latest high-density recording remarquables et restitués außerordentliche technology. The result? grâce aux techniques les plus Darbietungen der besten Sensational sound quality modernes de l’enregistrement Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? BRITTEN PETER GRIMES and definitive interpretations haute-définition. La qualité Sensationelle Klangqualität combined with the energy and sonore impressionnante und maßgebliche Sir Colin Davis emotion that you can only entourant ces interprétations Interpretationen, gepaart mit experience live in the concert d’anthologie se double de der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, London Symphony Orchestra hall. LSO Live lets everyone, l’énergie et de l’émotion que die man nur live im everywhere, feel the seuls les concerts en direct Konzertsaal erleben kann. excitement in the world’s peuvent offrit. LSO Live LSO Live lässt jedermann greatest music. For more permet à chacun, en toute an der aufregendsten, Glenn Winslade information visit circonstance, de vivre cette herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt Janice Watson www.lso.co.uk passion intense au travers teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr Anthony Michaels-Moore des plus grandes oeuvres erfahren möchten, schauen du répertoire. Sie bei uns herein: Catherine Wyn-Rogers Pour plus d’informations, www.lso.co.uk Jill Grove rendez vous sur le site James