The Voice of the New Renaissance: the Premiere Performances of Peter Pears Christopher Swanson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Download Booklet

SIGCD656_16ppBklt**.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 19/11/2020 17:06 Page 1 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. 16 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm SIGCD656_16ppBklt**.qxp_BookletSpread.qxt 19/11/2020 17:06 Page 2 CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. rEDISCOvErEd British Clarinet Concertos Dolmetsch • Maconchy • Spain-Dunk • Wishart 1. Cantilena (Poem) for Clarinet and Orchestra, Op. 51 * Susan Spain-Dunk (1880-1962) ............[11.32] Concertino for Clarinet and String Orchestra Elizabeth Maconchy (1907-1994) 2. I. Allegro .....................................................................................................................................................................................................................[5.01] 3. II. Lento .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................[6.33] 4. III. Allegro ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. [5.32] Concerto for Clarinet, Harp and Orchestra * Rudolph Dolmetsch (1906-1942) 5. I. Allegro moderato ......................................................................................................................................................................................[10.34] -

25114Booklet.Pdf

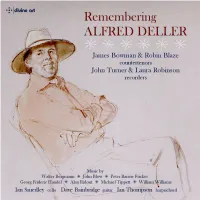

Remembering ALFRED DELLER Walter Bergmann (1902-1988) 1. Pastorale for countertenor & recorder (1946) 3.21 Michael Tippett (1905-1998) Four Inventions for two recorders (1954) 3.40 2. I. Andante 0.55 3. II. Allegro molto 0.34 4. III. Adagio 1.33 5. IV. Allegro moderato 0.36 Alan Ridout (1934-1996) 6. Soliloquy for countertenor, recorder, cello & harpsichord (1985) 5.10 William Williams (d.1701) Sonata in A minor for two recorders & continuo (c.1696) 6.01 7. I. Adagio 1.23 8. II. Vivace 2.58 9. III. Allegro 1.39 John Blow (1649-1708) Ode on the Death of Mr. Henry Purcell, for two countertenors, two recorders & continuo (1696) 32.20 10. I. 4.03 11. II. 4.29 12. III. 3.02 13. IV. 1.51 14. V. 2.32 15. VI. 3.40 16. VII. 2.38 George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Sonata in F major for two recorders & continuo (c.1707) 5.51 17. I. Allegro 2.14 18. II. Grave 1.28 19. III. Allegro 2.09 Peter Racine Fricker (1920-1990) 20. Elegy: The Tomb of St. Eulalia, Op. 25, for countertenor, cello & harpsichord (1955) 7.35 Walter Bergmann (1902-1988) Three Songs for countertenor & guitar (1973, rev. 1983) 4.53 21. No. 1 Mater cantans filio 1.26 22. No. 2 To Musick 2.36 23. No. 3 Chop-Cherry 0.50 Total duration: 59.36 JAMES BOWMAN countertenor (Blow, Fricker, Bergmann songs) ROBIN BLAZE countertenor (Bergmann Pastorale, Ridout, Blow) JOHN TURNER recorder (all works except Fricker & Bergmann Songs) LAURA ROBINSON recorder (Tippett, Williams, Handel) TIM SMEDLEY cello (Ridout, Williams, Blow, Handel, Fricker) DAVE BAINBRIDGE guitar (Bergmann Songs) IAN THOMPSON harpsichord (Ridout, Williams, Blow, Handel, Fricker) MEMORIES OF TIPPETT AND BERGMANN For those of us who grew up in the immediate post-war years, and who were interested in the revival of, and burgeoning enthusiasm for, early music, the names of Tippett and Bergmann are synonymous with those famous Schott editions of music by Purcell and his contemporaries. -

9 September 2021

9 September 2021 12:01 AM Uuno Klami (1900-1961) Serenades joyeuses Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Jussi Jalas (conductor) FIYLE 12:07 AM Johann Gottlieb Graun (c.1702-1771) Sinfonia in B flat major, GraunWV A:XII:27 Kore Orchestra, Andrea Buccarella (harpsichord) PLPR 12:17 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Violin Sonata in G minor Janine Jansen (violin), David Kuijken (piano) GBBBC 12:31 AM Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) Slavonic March in B flat minor 'March Slave' BBC Philharmonic, Rumon Gamba (conductor) GBBBC 12:41 AM Maria Antonia Walpurgis (1724-1780) Sinfonia from "Talestri, Regina delle Amazzoni" - Dramma per musica Batzdorfer Hofkapelle, Tobias Schade (director) DEWDR 12:48 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Sonata for piano (K.281) in B flat major Ingo Dannhorn (piano) AUABC 01:00 AM Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805) Quintet for guitar and strings in D major, G448 Zagreb Guitar Quartet, Varazdin Chamber Orchestra HRHRT 01:19 AM Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) Symphony No.3 (Op.27) "Sinfonia espansiva" Janne Berglund (soprano), Johannes Weisse (baritone), Stavanger Symphony Orchestra, Niklas Willen (conductor) NONRK 02:01 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Estampes, L.100 Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:14 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Etude in C minor Op.10'12 'Revolutionary' Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:17 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Etude in E major, Op.10'3 Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:20 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Etude in C minor Op.25'12 Kira Frolu (piano) ROROR 02:23 AM Constantin Silvestri (1913-1969) Chants nostalgiques, -

For All the Attention Paid to the Striking Passage of Thirty-Four

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Humanities Commons for Jane, on our thirty-fourth Accents of Remorse The good has never been perfect. There is always some flaw in it, some defect. First Sightings For all the attention paid to the “interview” scene in Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd, its musical depths have proved remarkably resistant to analysis and have remained unplumbed. This striking passage of thirty-four whole-note chords has probably attracted more comment than any other in the opera since Andrew Porter first spotted shortly after the 1951 premiere that all the chords harmonize members of the F major triad, leading to much discussion over whether or not the passage is “in F major.” 1 Beyond Porter’s perception, the structure was far from obvious, perhaps in some way unprecedented, and has remained mysterious. Indeed, it is the undisputed gnomic power of its strangeness that attracted (and still attracts) most comment. Arnold Whittall has shown that no functional harmonic or contrapuntal explanation of the passage is satisfactory, and proceeded from there to make the interesting assertion that that was the point: The “creative indecision”2 that characterizes the music of the opera was meant to confront the listener with the same sort of difficulty as the layers of irony in Herman Melville’s “inside narrative,” on which the opera is based. To quote a single sentence of the original story that itself contains several layers of ironic ambiguity, a sentence thought by some—I believe mistakenly—to say that Vere felt no remorse: 1. -

5099943343256.Pdf

Benjamin Britten 1913 –1976 Winter Words Op.52 (Hardy ) 1 At Day-close in November 1.33 2 Midnight on the Great Western (or The Journeying Boy) 4.35 3 Wagtail and Baby (A Satire) 1.59 4 The Little Old Table 1.21 5 The Choirmaster’s Burial (or The Tenor Man’s Story) 3.59 6 Proud Songsters (Thrushes, Finches and Nightingales) 1.00 7 At the Railway Station, Upway (or The Convict and Boy with the Violin) 2.51 8 Before Life and After 3.15 Michelangelo Sonnets Op.22 9 Sonnet XVI: Si come nella penna e nell’inchiostro 1.49 10 Sonnet XXXI: A che piu debb’io mai l’intensa voglia 1.21 11 Sonnet XXX: Veggio co’ bei vostri occhi un dolce lume 3.18 12 Sonnet LV: Tu sa’ ch’io so, signior mie, che tu sai 1.40 13 Sonnet XXXVIII: Rendete a gli occhi miei, o fonte o fiume 1.58 14 Sonnet XXXII: S’un casto amor, s’una pieta superna 1.22 15 Sonnet XXIV: Spirto ben nato, in cui so specchia e vede 4.26 Six Hölderlin Fragments Op.61 16 Menschenbeifall 1.26 17 Die Heimat 2.02 18 Sokrates und Alcibiades 1.55 19 Die Jugend 1.51 20 Hälfte des Lebens 2.23 21 Die Linien des Lebens 2.56 2 Who are these Children? Op.84 (Soutar ) (Four English Songs) 22 No.3 Nightmare 2.52 23 No.6 Slaughter 1.43 24 No.9 Who are these Children? 2.12 25 No. -

George Frideric Handel Cc 9127 George Frideric Handel

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL CC 9127 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL male lead in The Bear for Hemsley, who played it under the composer on BBC Television in George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) 1970. His book Singing and Imagination is a lucid guide to his finely-honed art. = `çåÅÉêíç=áå=_JÑä~í=ets=OVQ=léK=Q=kçK=S=ENTPSF= NNKNN Geraint Jones (1917-98). The son of a Glamorgan minister, Jones studied at the Royal 1-3 I Andante allegro 3.53 2 II Larghetto 4.31 3 III Allegro moderato 2.53 Academy of Music before being rejected for World War II service on grounds of poor health. Osian Ellis, harp. The Boyd Neel Orchestra directed by Thurston Dart Determined to ‘do his bit’, he made his debut as a harpsichordist in 1940 at one of Myra Hess’s A BBC studio broadcast, 26 February 1957 National Gallery concerts, later touring widely with his wife, the violinist Winifred Roberts. After the war he became highly influential in the ‘authentic’ baroque movement, forming his own = ^éçääç=É=a~ÑåÉ=ets=NOO=ENTNMF= QPKMR orchestra for the acclaimed performances at London’s Mermaid Theatre in 1951 of Dido and Aeneas, with Kirsten Flagstad and Thomas Hemsley. Jones’s many recordings included Dido 4 Recitative and Aria Apollo ‘La terra è liberata … Pende il ben dell’universo’ 5.18 (The earth is set free … The good of the universe) with those singers (plus Elisabeth Schwarzkopf as Belinda and Arda Mandikian as the 5 Recitative and Aria Apollo 3.54 Sorceress) as well as music by Bach, Handel and Mozart. -

Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Piano Tamara Stefanovich, Piano

Thursday, March 12, 2015, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Pierre-Laurent Aimard, piano Tamara Stefanovich, piano The Piano Music of Pierre Boulez PROGRAM Pierre Boulez (b. 1925) Notations (1945) I. Fantastique — Modéré II. Très vif III. Assez lent IV. Rythmique V. Doux et improvisé VI. Rapide VII. Hiératique VIII. Modéré jusqu'à très vif IX. Lointain — Calme X. Mécanique et très sec XI. Scintillant XII. Lent — Puissant et âpre Boulez Sonata No. 1 (1946) I. Lent — Beaucoup plus allant II. Assez large — Rapide Boulez Sonata No. 2 (1947–1948) I. Extrêmement rapide II. Lent III. Modéré, presque vif IV. Vif INTERMISSION PLAYBILL PROGRAM Boulez Sonata No. 3 (1955–1957; 1963) Formant 3 Constellation-Miroir Formant 2 Trope Boulez Incises (1994; 2001) Boulez Une page d’éphéméride (2005) Boulez Structures, Deuxième livre (1961) for two pianos, four hands Chapitre I Chapitre II (Pièces 1–2, Encarts 1–4, Textes 1–6) Funded, in part, by the Koret Foundation, this performance is part of Cal Performances’ – Koret Recital Series, which brings world-class artists to our community. This performance is made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsor Françoise Stone. Hamburg Steinway piano provided by Steinway & Sons, San Francisco. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES PROGRAM NOTES THE PROGRAM AT A GLANCE the radical break with tradition that his music supposedly embodies. If Boulez belongs to an Tonight’s program includes the complete avant-garde, it is to a French avant-garde tra - piano music of Pierre Boulez, as well as a per - dition dating back two centuries to Berlioz formance of the second book of Structures for and Delacroix, and his attitudes are deeply two pianos. -

BENJAMIN BRITTEN's USE of the Passacagt.IA Bernadette De Vilxiers a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts University of the Wi

BENJAMIN BRITTEN'S USE OF THE PASSACAGt.IA Bernadette de VilXiers A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Johannesburg 1985 ABSTRACT Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) was perhaps the most prolific cooposer of passaca'?' las in the twentieth century. Die present study of his use of tli? passac^.gl ta font is based on thirteen selected -assacaalias which span hin ire rryi:ivc career and include all genre* of his music. The passacaglia? *r- occur i*' the follovxnc works: - Piano Concerto, Op. 13, III - Violin Concerto, Op. 15, III - "Dirge" from Serenade, op. 31 - Peter Grimes, Op. 33, Interlude IV - "Death, be not proud!1' from The Holy Sonnets o f John Donne, Op. 35 - The Rape o f Lucretia, op. 37, n , ii - Albert Herring, Op. 39, III, Threnody - Billy Budd, op. 50, I, iii - The Turn o f the Screw, op . 54, II, viii - Noye '8 Fludde, O p . 59, Storm - "Agnu Dei" from War Requiem, Op. 66 - Syrrvhony forCello and Orchestra, Op. 68, IV - String Quartet no. 3, Op. 94, V The analysis includes a detailed investigation into the type of ostinato themes used, namely their structure (lengUi, contour, characteristic intervals, tonal centre, metre, rhythm, use of sequence, derivation hod of handling the ostinato (variations in length, tone colouJ -< <>e register, ten$>o, degree of audibility) as well as the influence of the ostinato theme on the conqposition as a whole (effect on length, sectionalization). The accompaniment material is then brought under scrutiny b^th from the point of view of its type (thematic, motivic, unrelated counterpoints) and its importance within the overall frarework of the passacaglia. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

The Scottish Viola a Tribute to Watson Forbes

NI 6180 The Scottish Viola A tribute to WAtson Forbes For further information please visit MArtin outrAM viola www.martinoutram.com www.wyastone.co.uk JuliAn rolton piano The Scottish Viola A tribute to WAtson Forbes As an accompanist he recorded an piano trios entitled Borderlands on Campion Pietro Nardini (arr Forbes/Richardson): Concerto in G minor acclaimed CD of Russian song with Cameo which attracted exceptional reviews. 1. Allegro moderato 4:28 the mezzo-soprano Helen Lawrence in The Chagall Trio has appeared at festivals 2. Andante affettuoso 2:57 3. Allegretto 2:35 celebration of Pushkin’s bi-centenary. throughout Britain, broadcasts on BBC He has appeared with Richard Jackson Radio 3 and has given premieres of works Robin Orr: Sonata 4. Introduction and Fugue 5:01 in the Almeida Opera Festival and, with by Nicholas Maw, David Matthews and Philip 5. Elegy 4:24 Mary Wiegold, performed a programme Grange. During the Royal Academy of Art’s 6. Scherzetto 1:55 of songs by Howard Skempton in the Chagall exhibition, “Love and the Stage”, 7. Finale 4:51 Aldeburgh Festival. He regularly plays for they were invited to present a programme of Alan Richardson: Sonata the master-classes of such eminent singers music and words celebrating the life of their 8. Poco lento - Allegro 6:17 as Galina Vishnevskaya, Phyllis Bryn-Julson namesake. With the actor Samuel West, the 9. Molto vivace: leggiero e volante 2:24 10. Lento 7:06 and Anthony Rolfe Johnson at the Snape Trio repeated this programme in the Wigmore 11. Allegro energico 4:02 Maltings. -

That to See How Britten Handles the Dramatic and Musical Materials In

BOOKS 131 that to see how Britten handles the dramatic and musical materials in the op- era is "to discover anew how from private pain the great artist can fashion some- thing that transcends his own individual experience and touches all humanity." Given the audience to which it is directed, the book succeeds superbly. Much of it is challenging and stimulating intellectually, while avoiding exces- sive weightiness, and at the same time, it is entertaining in the very best sense of the word. Its format being what it is, there are inevitable duplications of information, and I personally found the Garbutt and Garvie articles less com- pelling than the remainder of the book. The last two articles of Brett's, excel- lent as they are, also tend to be a little discursive, but these are minor reserva- tions. For anyone who cares for this masterwork of twentieth-century opera, Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/4/3/131/1587210 by guest on 01 October 2021 or for Britten and his music, this book is obligatory reading. Carlisle Floyd Peter Grimes/Gloriana Benjamin Britten English National Opera/Royal Opera Guide 24 Nicholas John, series editor London: John Calder; New York: Riverrun Press, 1983 128 pages, $5.95 (paper) The English National Opera/Royal Opera Guides, small paperbacks with siz- able contents, are among the best introductions available to the thirty-plus operas published in the series so far. Each guide includes some essays by ac- knowledged authorities on various aspects of its subject, followed by a table of major musical themes, a complete libretto (original language plus transla- tion), a brief bibliography, and a discography.