Albert Herring Benjamin Britten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Jonathan Summers B) CATEGORY: Opera Singer / Baritone C) POSITION: Freelance

1a) NAME: Jonathan Summers b) CATEGORY: Opera singer / baritone c) POSITION: Freelance 2a) PERSONAL DETAILS: date of birth / place / country 2nd October, 1946; Melbourne; Australia b) MARITAL STATUS: date of marriage / name of spouse / number of children 29th March 1969, Melbourne Australia; Lesley; 3 children 3) PREVIOUS OCCUPATIONS: dates / occupation 1965-1974 Freelance singer/concert artist 1970-1974 Technical operator/recording engineer Australian Broadcasting Commission, Melbourne 4) EDUCATION: dates / institution / city / teacher Secondary : Melbourne; Macleod High School Tertiary : Melbourne; Prahran Technical College (Art School) 1964-1974 Melbourne; Bettine McCaughan, voice teacher 1972-1973 Melbourne;National Theatre Opera School 1974-1980 London; Otakar Kraus, voice teacher 5) PROFESSIONAL DEBUT: date / opera company / role / opera / cast Nov 1975; Kent Opera; title role in Verdi's Rigoletto; Congress Theater, Eastbourne, UK; producer: Jonathan Miller; conductor: Roger Norrington; David Hillman (Duke), Meryl Drower (Gilda), Sarah Walker (Maddalena), Malcolm King (Sparafucile) 6) EARLY CAREER WITH BRIEF RESUME: dates / opera house or company / role / opera Feb 1976; University College London Opera; title role in Macbeth (orig. 1847 version); producer: John Moody; conductor: George Badachoni Sep 1976; Glyndebourne Touring Opera; title role in Falstaff; producer: Jean-Pierre Ponnelle; conductor: Kenneth Montgomery Oct 1976; joined the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, as a company principal Nov 1976; English National Opera -

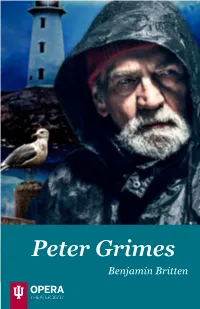

Peter Grimes Benjamin Britten

Peter Grimes Benjamin Britten THEATER 16/17 FOR YOUR INFORMATION Do you want more information about upcoming events at the Jacobs School of Music? There are several ways to learn more about our recitals, concerts, lectures, and more! Events Online Visit our online events calendar at music.indiana.edu/events: an up-to-date and comprehensive listing of Jacobs School of Music performances and other events. Events to Your Inbox Subscribe to our weekly Upcoming Events email and several other electronic communications through music.indiana.edu/publicity. Stay “in the know” about the hundreds of events the Jacobs School of Music offers each year, most of which are free! In the News Visit our website for news releases, links to recent reviews, and articles about the Jacobs School of Music: music.indiana.edu/news. Musical Arts Center The Musical Arts Center (MAC) Box Office is open Monday – Friday, 11:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. Call 812-855-7433 for information and ticket sales. Tickets are also available at the box office three hours before any ticketed performance. In addition, tickets can be ordered online at music.indiana.edu/boxoffice. Entrance: The MAC lobby opens for all events one hour before the performance. The MAC auditorium opens one half hour before each performance. Late Seating: Patrons arriving late will be seated at the discretion of the management. Parking Valid IU Permit Holders access to IU Garages EM-P Permit: Free access to garages at all times. Other permit holders: Free access if entering after 5 p.m. any day of the week. -

Press Information Eno 2013/14 Season

PRESS INFORMATION ENO 2013/14 SEASON 1 #ENGLISHENO1314 NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 CONTENTS Autumn 2013 4 FIDELIO Beethoven 6 DIE FLEDERMAUS Strauss 8 MADAM BUtteRFLY Puccini 10 THE MAGIC FLUte Mozart 12 SATYAGRAHA Glass Spring 2014 14 PeteR GRIMES Britten 18 RIGOLetto Verdi 20 RoDELINDA Handel 22 POWDER HeR FAce Adès Summer 2014 24 THEBANS Anderson 26 COSI FAN TUtte Mozart 28 BenvenUTO CELLINI Berlioz 30 THE PEARL FISHERS Bizet 32 RIveR OF FUNDAMent Barney & Bepler ENGLISH NATIONAL OPERA Press Information 2013/4 3 FIDELIO NEW PRODUCTION BEETHoven (1770–1827) Opens: 25 September 2013 (7 performances) One of the most sought-after opera and theatre directors of his generation, Calixto Bieito returns to ENO to direct a new production of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio. Bieito’s continued association with the company shows ENO’s commitment to highly theatrical and new interpretations of core repertoire. Following the success of his Carmen at ENO in 2012, described by The Guardian as ‘a cogent, gripping piece of work’, Bieito’s production of Fidelio comes to the London Coliseum after its 2010 premiere in Munich. Working with designer Rebecca Ringst, Bieito presents a vast Escher-like labyrinth set, symbolising the powerfully claustrophobic nature of the opera. Edward Gardner, ENO’s highly acclaimed Music Director, 2013 Olivier Award-nominee and recipient of an OBE for services to music, conducts an outstanding cast led by Stuart Skelton singing Florestan and Emma Bell as Leonore. Since his definitive performance of Peter Grimes at ENO, Skelton is now recognised as one of the finest heldentenors of his generation, appearing at the world’s major opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera, New York, and Opéra National de Paris. -

Owen Wingrave

OWEN WINGRAVE Oper in zwei Akten von Benjamin Britten Libretto von Myfanwy Piper nach der gleichnamigen Kurzgeschichte von Henry James Eine Veranstaltung des Departements für Oper und Musiktheater in Kooperation mit dem Departement für Bühnen- und Kostümgestaltung, Film- und Ausstellungsarchitektur Montag, 20. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr Dienstag, 21. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr Mittwoch, 22. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr (Livestream) Donnerstag, 23. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr Max Schlereth Saal Universität Mozarteum Mirabellplatz 1 BESETZUNG Owen Wingrave Taesung Kim (20.1./22.1.)/Benjamin Sattlecker (21.1./23.1.) Musikalische Einstudierung Julia Antonovitch, Dariusz Burnecki, Stefan Müller, Walewein Witten Spencer Coyle Xiaofei Liu (20.1./22.1.)/Qi Wang (21.1./23.1.) Szenische Assistenz Agnieszka Lis Lechmere Johannes Hubmer Schauspielcoaching Natalie Forester Miss Wingrave Julia Heiler Sprachcoaching Theresa McDougall Mrs. Coyle Veronika Loy (20.1./22.1.)/Sophie Negoïta (21.1./23.1.) Szenischer Kampf Ulf Kirschhofer Mrs. Julian Chelsea Kolic´ (20.1./22.1.)/Bryndís Guðjónsdóttir (21.1./23.1.) Maske Jutta Martens Kate Vera Bitter Übertitel Leopold Eibensteiner General Wingrave Yu Hsuan Cheng Technische Leitung Andreas Greiml/Thomas Hofmüller/Alexander Lährm Narrator Richard Glöckner Werkstättenleitung Thomas Hofmüller Kinderchor Antonella Hohenadler, Felix Knittel, Florian Kritzinger, Lennart Malm, Sophie Münch, Noah Obermair, Niklas Plasse, Lichtgestaltung Michael Becke Leonhard Radauer Tontechnik Susanne Gasselsberger Musikalische Leitung Gernot Sahler -

Copland As Mentor to Britten, 1939-1942

'You absolutely owe it to England to stay here': Copland as mentor to Britten, 1939-1942 Suzanne Robinson Few details of the circumstances of Benjamin Copland to visit him for the weekend at his home in a Britten's stay in America in the years 1939-42 were converted mill in Snape. On this occasion they familiar- known before the publication in 1991of Britten's letters ised one another with their music; Copland played his and, in 1992, of a biography by Humphrey Carpenter. school opera, The Second Hurricane, singing all the parts And with the exception of a short article on Aaron himself, while Britten performed the first version of his Copland and Britten in an Aldeburgh Festival Programme Piano ~oncerto.~Being July, and England, at the first ~ook,llittle attention has been paid to the significance sign of sunshine the locals escorted their visitor to one of Britten's exposure to Copland's music, which Britten of Suffolk's pebbled beaches (which Copland described regarded as the best America had to offer. More than 20 as a 'shingle'). Copland realised that perhaps he was letters survive between 'Benjie' and 'my dearest Aaron', more accustomed to the effects of the sun, when Ibefore the majority of them belonging to the war years when long it became clear that the assembled group was in Copland was resident in New York and Britten was, for danger of "roasting". When I politely pointed out the the most part, nearby in Long ~sland.~Britten fre- obvious result to be expected from lying unprotected quently referred to Copland as his 'very dear friend', on the beach, I was told: "But we see the sun so and even 'Father' (Copland was the senior of the two rarely"'? When he returned to America, copland wrote by 13 years). -

BENJAMIN BRITTEN's USE of the Passacagt.IA Bernadette De Vilxiers a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts University of the Wi

BENJAMIN BRITTEN'S USE OF THE PASSACAGt.IA Bernadette de VilXiers A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Johannesburg 1985 ABSTRACT Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) was perhaps the most prolific cooposer of passaca'?' las in the twentieth century. Die present study of his use of tli? passac^.gl ta font is based on thirteen selected -assacaalias which span hin ire rryi:ivc career and include all genre* of his music. The passacaglia? *r- occur i*' the follovxnc works: - Piano Concerto, Op. 13, III - Violin Concerto, Op. 15, III - "Dirge" from Serenade, op. 31 - Peter Grimes, Op. 33, Interlude IV - "Death, be not proud!1' from The Holy Sonnets o f John Donne, Op. 35 - The Rape o f Lucretia, op. 37, n , ii - Albert Herring, Op. 39, III, Threnody - Billy Budd, op. 50, I, iii - The Turn o f the Screw, op . 54, II, viii - Noye '8 Fludde, O p . 59, Storm - "Agnu Dei" from War Requiem, Op. 66 - Syrrvhony forCello and Orchestra, Op. 68, IV - String Quartet no. 3, Op. 94, V The analysis includes a detailed investigation into the type of ostinato themes used, namely their structure (lengUi, contour, characteristic intervals, tonal centre, metre, rhythm, use of sequence, derivation hod of handling the ostinato (variations in length, tone colouJ -< <>e register, ten$>o, degree of audibility) as well as the influence of the ostinato theme on the conqposition as a whole (effect on length, sectionalization). The accompaniment material is then brought under scrutiny b^th from the point of view of its type (thematic, motivic, unrelated counterpoints) and its importance within the overall frarework of the passacaglia. -

Big Ship One Sheet

A Simple Films Development project THE TOUR OF 2718 RIVERSIMPLE JOHN FILMSSTATION LTD ROAD THE BIGProducer: Stuart Cresswell SHIPWriter: Julie Welch Nova Scotia,River John, B0K 1N0 : TELEPHONE 1-902-701-2483 Armstrong’s [email protected] EMAIL Australians won 8 successive test matches, a feat International mini-series, unequalled in test historical sports drama match history. A STORY OF IMMENSE CHARACTERS. FOR INSTANCE... WARWICK ARMSTRONG - THE BIG SHIP Huge in stature and personality on and off the pitch, Armstrong battled and battered opponents and had a long-running row with Tour Manager Syd Smith to protect his players. He was built to win - and bent the rules to meet Warwick Armstrong’s touring Australians, 1921 his ends. ARCHIE MACLAREN - THE OPPORTUNIST Aging ex-England Captain, cast aside by the MCC, he chipped away at the establishment to have the chance to pick an English team of no- hopers who would provide one of the greatest upsets in sporting history. NEVILLE CARDUS - THE CRICKET ROMANTIC Lord Tennyson batting bravely one-handed Archie MacLaren (L), 1921 Cricket writer and critic who has influenced sports journalists since. The David and Goliath “Australians have made game at the Saffrons was “the only scoop of my cricket a war game...with career.” an intensity of purpose too deadly for a mere JACK GREGORY - THE DEMON BOWLER game.” One half of Australia’s twin-pace bowling attack, described as ‘fearsome’ he was Wisden’s Neville Cardus top cricketer in 1922. The Tour of The Big Ship |TV Mini-series | International co-pro potential | Historical Sports Drama THE TOUR OF THE BIG SHIP! PAGE2 The Saffrons - The cricket pitch in Eastbourne that was the venue of Armstrong and MacLaren’s historic game C.B. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

That to See How Britten Handles the Dramatic and Musical Materials In

BOOKS 131 that to see how Britten handles the dramatic and musical materials in the op- era is "to discover anew how from private pain the great artist can fashion some- thing that transcends his own individual experience and touches all humanity." Given the audience to which it is directed, the book succeeds superbly. Much of it is challenging and stimulating intellectually, while avoiding exces- sive weightiness, and at the same time, it is entertaining in the very best sense of the word. Its format being what it is, there are inevitable duplications of information, and I personally found the Garbutt and Garvie articles less com- pelling than the remainder of the book. The last two articles of Brett's, excel- lent as they are, also tend to be a little discursive, but these are minor reserva- tions. For anyone who cares for this masterwork of twentieth-century opera, Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/4/3/131/1587210 by guest on 01 October 2021 or for Britten and his music, this book is obligatory reading. Carlisle Floyd Peter Grimes/Gloriana Benjamin Britten English National Opera/Royal Opera Guide 24 Nicholas John, series editor London: John Calder; New York: Riverrun Press, 1983 128 pages, $5.95 (paper) The English National Opera/Royal Opera Guides, small paperbacks with siz- able contents, are among the best introductions available to the thirty-plus operas published in the series so far. Each guide includes some essays by ac- knowledged authorities on various aspects of its subject, followed by a table of major musical themes, a complete libretto (original language plus transla- tion), a brief bibliography, and a discography. -

Download Booklet

- PB - SYMPHONIES 1 & 2 The First and Second Symphonies of Sibelius Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) The music critic Neville Cardus, when reviewing a concert Besides considering the various influences on of the Sibelius First and Second Symphonies, remarked these two magnificent works, it is instructive to that he would be happy to discard the later symphonies understand the origins of both. Already 34 when in favour of the first two. He was referring to the his First Symphony was premiered in 1899, Sibelius Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39 * [34.17] emotional impact of these early works compared to the was known for a number of nationalistic orchestral 1 I. Andante, ma non troppo [9.39] more restrained glories of the later ones. Sometimes it is works heavily influenced by Finnish literature 2 hard to disagree with this opinion, particularly when both and landscape such as En Saga, Kullervo, the II. Andante (ma non troppo lento) [9.26] symphonies are given such overtly romantic readings Karelia Suite and the Lemminkainen Legends. 3 III. Scherzo–Allegro [4.45] as those conducted by Leopold Stokowski on this CD. Certain Finnish critics were, however, impatient with 4 IV. Finale (Quasi una Fantasia)–Andante [10.17] Sibelius himself turned to the high priests of romantic Sibelius for not writing an abstract symphony of music for his influences. With the First Symphony, he the kind traditionally associated with the musical sought guidance from the Russian school typified by capitals of Europe. Sibelius must also have been Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. -

Britten's Acoustic Miracles in Noye's Fludde and Curlew River

Britten’s Acoustic Miracles in Noye’s Fludde and Curlew River A thesis submitted by Cole D. Swanson In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music TUFTS UNIVERSITY May 2017 Advisor: Alessandra Campana Readers: Joseph Auner Philip Rupprecht ii ABSTRACT Benjamin Britten sought to engage the English musical public through the creation of new theatrical genres that renewed, rather than simply reused, historical frameworks and religious gestures. I argue that Britten’s process in creating these genres and their representative works denotes an operation of theatrical and musical “re-enchantment,” returning spiritual and aesthetic resonance to the cultural relics of a shared British heritage. My study focuses particularly on how this process of renewal further enabled Britten to engage with the state of amateur and communal music participation in post-war England. His new, genre-bending works that I engage with represent conscious attempts to provide greater opportunities for amateur performance, as well cultivating sonically and thematically inclusive sound worlds. As such, Noye’s Fludde (1958) was designed as a means to revive the musical past while immersing the Aldeburgh Festival community in present musical performance through Anglican hymn singing. Curlew River (1964) stages a cultural encounter between the medieval past and the Japanese Nō theatre tradition, creating an atmosphere of sensory ritual that encourages sustained and empathetic listening. To explore these genre-bending works, this thesis considers how these musical and theatrical gestures to the past are reactions to the post-war revivalist environment as well as expressions of Britten’s own musical ethics and frustrations.