Saurashtra University Library Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Nov-2019.Qxd

C M C M Y B Y B RNI No: JKENG/2012/47637 Email: [email protected] POSTAL REGD NO- JK/485/2016-18 Internet Edition www.truthprevail.com Truth Prevail Epaper: epaper.truthprevail.com We failed to execute our skills properly: Rohit Sharma after losing to Bangladesh 3 5 12 2-Day orientation program Dissolution of 200 year old State an Multipronged strategy to check fire commences in Srinagar insult to people : Harsh incidents in Hotels across J&K VOL: 8 NO: 303 JAMMU AND KASHMIR, TUESDAy , NOVEMBER 05, 2019 DAILy PAGES 12 Rs. 2/- IInnssiiddee Darbar opens at Jammu Assembly secretariat re-opens in Jammu JAMMU, NOVEMBER took stock of the facilities on Terrorist hideout 04 : Speaker Legislative re-opening after move of Assembly, Nirmal Singh offices from Srinagar. The busted in orchard Lt. Governor accorded ceremonial reception on his arrival along with officers today Speaker interacted with the in Sopore inspected various sections of staff members and enquired Srinagar : In a joint Assembly Secretariat and about their working. search by the Jammu and at Civil Secretariat, interacts with officers, visits PHQ Kashmir Police and security JAMMU, NOVEMBER Secretary, B V R important and urgent adminis - erated the resolve of the gov - where he received a Guard of Chief Justice Gita Mittal presented forces on Monday, a terrorist 04 : The offices opened here Subrahmanyam, Director trative issues. In another ernment for tirelessly work - Honour. Sh. Dilbag Singh, hideout was unearthed and today as a part of Darbar General of Police, Dilbag DGP, and other senior Police ceremonial guard of honour destroyed in Sopore Move, after their closing at Singh, Administrative officers interacted with the Lt. -

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

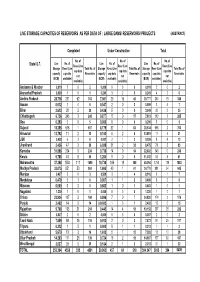

Live Storage Capacities of Reservoirs As Per Data of : Large Dams/ Reservoirs/ Projects (Abstract)

LIVE STORAGE CAPACITIES OF RESERVOIRS AS PER DATA OF : LARGE DAMS/ RESERVOIRS/ PROJECTS (ABSTRACT) Completed Under Construction Total No. of No. of No. of Live No. of Live No. of Live No. of State/ U.T. Resv (Live Resv (Live Resv (Live Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of cap data cap data cap data capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs not not not (BCM) available) (BCM) available) (BCM) available) available) available) available) Andaman & Nicobar 0.019 20 2 0.000 00 0 0.019 20 2 Arunachal Pradesh 0.000 10 1 0.241 32 5 0.241 42 6 Andhra Pradesh 28.716 251 62 313 7.061 29 16 45 35.777 280 78 358 Assam 0.012 14 5 0.547 20 2 0.559 34 7 Bihar 2.613 28 2 30 0.436 50 5 3.049 33 2 35 Chhattisgarh 6.736 245 3 248 0.877 17 0 17 7.613 262 3 265 Goa 0.290 50 5 0.000 00 0 0.290 50 5 Gujarat 18.355 616 1 617 8.179 82 1 83 26.534 698 2 700 Himachal 13.792 11 2 13 0.100 62 8 13.891 17 4 21 J&K 0.028 63 9 0.001 21 3 0.029 84 12 Jharkhand 2.436 47 3 50 6.039 31 2 33 8.475 78 5 83 Karnatka 31.896 234 0 234 0.736 14 0 14 32.632 248 0 248 Kerala 9.768 48 8 56 1.264 50 5 11.032 53 8 61 Maharashtra 37.358 1584 111 1695 10.736 169 19 188 48.094 1753 130 1883 Madhya Pradesh 33.075 851 53 904 1.695 40 1 41 34.770 891 54 945 Manipur 0.407 30 3 8.509 31 4 8.916 61 7 Meghalaya 0.479 51 6 0.007 11 2 0.486 62 8 Mizoram 0.000 00 0 0.663 10 1 0.663 10 1 Nagaland 1.220 10 1 0.000 00 0 1.220 10 1 Orissa 23.934 167 2 169 0.896 70 7 24.830 174 2 176 Punjab 2.402 14 -

A.R. Desai: Social Background of Indian Nationalism

M.A. (Sociology) Part I (Semester-II) Paper III L .No. 2.2 Author : Prof. B.K. Nagla A.R. Desai: Social Background of Indian Nationalism Structure 2.2.0 Objectives 2.2.1 Introduction to the Author 2.2.2 Writing of Desai 2.2.3 Nationalism 2.2.3.1 Nation : E.H. Carr's definition 2.2.3.2 National Sentiment 2.2.3.3 Study of Rise and Growth of Indian Nationalism 2.2.3.4 Social Background of Indian Nationalism 2.2.4 Discussion 2.2.5 Nationalism in India, Its Chief Phases 2.2.5.1 First Phase 2.2.5.2 Second Phase 2.2.5.3 Third Phase 2.2.5.4 Fourth Phase 2.2.5.5 Fifth Phase 2.2.6 Perspective 2.2.7 Suggested Readings 2.2.0 Objectives: After going through this lesson you will be able to : • introduce the Author. • explain Nationalism. • discuss rise and growth of Indian Nationalism. • know Nationalism in India and its different phases. 2.2.1 Introduction to the Author A.R.Desai: (1915-1994) Akshay Ramanlal Desai was born on April 16, 1915 at Nadiad in Central Gujarat and died on November 12, 1994 at Baroda in Gujarat. In his early ears, he was influenced by his father Ramanlal Vasantlal Desai, a well-known litterateur who inspired the youth in Gujarat in the 30s. A.R.Desai took part in student movements in Baroda, Surat and Bombay. He graduated from the university of M.A. (Sociology) Part I 95 Paper III Bombay, secured a law degree and a Ph.D. -

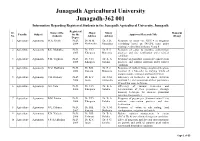

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001 Information Regarding Registered Students in the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh Registered Sr. Name of the Major Minor Remarks Faculty Subject for the Approved Research Title No. students Advisor Advisor (If any) Degree 1 Agriculture Agronomy M.A. Shekh Ph.D. Dr. M.M. Dr. J. D. Response of castor var. GCH 4 to irrigation 2004 Modhwadia Gundaliya scheduling based on IW/CPE ratio under varying levels of biofertilizers, N and P 2 Agriculture Agronomy R.K. Mathukia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. P. J. Response of castor to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Marsonia practices and zinc fertilization under rainfed condition 3 Agriculture Agronomy P.M. Vaghasia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of groundnut to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Golakia practices and sulphur nutrition under rainfed condition 4 Agriculture Agronomy N.M. Dadhania Ph.D. Dr. B.B. Dr. P. J. Response of multicut forage sorghum [Sorghum 2006 Kaneria Marsonia bicolour (L.) Moench] to varying levels of organic manure, nitrogen and bio-fertilizers 5 Agriculture Agronomy V.B. Ramani Ph.D. Dr. K.V. Dr. N.M. Efficiency of herbicides in wheat (Triticum 2006 Jadav Zalawadia aestivum L.) and assessment of their persistence through bio assay technique 6 Agriculture Agronomy G.S. Vala Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Efficiency of various herbicides and 2006 Khanpara Golakia determination of their persistence through bioassay technique for summer groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 7 Agriculture Agronomy B.M. Patolia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) to 2006 Khanpara Golakia moisture conservation practices and zinc fertilization 8 Agriculture Agronomy N.U. -

Formative Years

CHAPTER 1 Formative Years Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a seaside town in western India. At that time, India was under the British raj (rule). The British presence in India dated from the early seventeenth century, when the English East India Company (EIC) first arrived there. India was then ruled by the Mughals, a Muslim dynasty governing India since 1526. By the end of the eighteenth century, the EIC had established itself as the paramount power in India, although the Mughals continued to be the official rulers. However, the EIC’s mismanagement of the Indian affairs and the corruption among its employees prompted the British crown to take over the rule of the Indian subcontinent in 1858. In that year the British also deposed Bahadur Shah, the last of the Mughal emperors, and by the Queen’s proclamation made Indians the subjects of the British monarch. Victoria, who was simply the Queen of England, was designated as the Empress of India at a durbar (royal court) held at Delhi in 1877. Viceroy, the crown’s representative in India, became the chief executive-in-charge, while a secretary of state for India, a member of the British cabinet, exercised control over Indian affairs. A separate office called the India Office, headed by the secretary of state, was created in London to exclusively oversee the Indian affairs, while the Colonial Office managed the rest of the British Empire. The British-Indian army was reorganized and control over India was established through direct or indirect rule. The territories ruled directly by the British came to be known as British India. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

POTTERY ANALYSIS of Kuntasl CHAPTEH IV

CHAPTER IV POTTERY ANALYSIS OF KUNTASl CHAPTEH IV POTTBKY ANALYSIS OF KUNTASI IV-A. KUNTASI, A HARAPPAN SITE IN WESTKRN SAUKASHTKA IV-A-1. Gujarat and its regions The ancient site of Kuntasi (22" 53’ OO” N - 70“ :J2 ’ OO" H '; Taluka Maliya, Dislricl l^ajkot) lies about two kilomelres soulh- easl of the present village, on the right (north) bank of the meandering, ephemeral nala of Zinzoda. The village of Kuntasi lies just on the border of three districts, viz., Rajkot, Jamnagar and Kutch (Fig. 1). Geographically, Kuntasi is located at the north western corner of Saurashtra bordering Kutch, almost at the mouth of the Little Rann. Thus, the location of the site itself is very interesting and unique. Three regions of Gujarat^ : Gujarat is roughly divided into three divisions, namely Anarta (northern Gujarat), Lata (southern Gujarat from Mahi to Tapi rivers) and Saurashtra (Sankalia 1941: 4- 6; Shah 1968: 56-62). The recent anthropological field survey has also revealed major “ eco-cultural” zones or the folk regions perceived by the local people in Gujarat (North, South and Saurashtra) identical with the traditional divisions, adding Kutch as the fourth region (Singh 1992: 34 and Map 1). These divisions also agree well more or less with the physiographical divisions, which are also broadly divided into three distinct units, viz. the mainland or the plains of (North and South combined) Gujarat, the Saurashtra peninsular and Kutch (Deshpande 1992: 119)'. -72- The mainland or the plains of Gujarat is characleri zed by a flat tract of alluvium formed by the rivers such as Banas and Kupen X draining out into the Little Rann of Kutch, and Sabarmati, Mahi, Narmada, Tapi, etc.(all these rivers are almost perennial) into the Gulf of Khambhat. -

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1 Chapter: 1 Introduction Substantial research work has been conducted on the genre of the novel and its various aspects in English as well as in Gujarati literature, but the study focusing on the theme of the region and regionality in Indian writing in English and the Gujarati novel, especially in the novels of R. K. Narayan (1906 to 2001) and Pannalal Patel (1912 to 1989), has scarcely been carried out in a comparative mode. This dissertation is aimed at studying the representation of the region in the novels of R. K. Narayan and Pannalal Patel from the point of view of postcolonial studies by highlighting the socio-cultural, political and religious dimensions their works. It is possible to locate the postcolonial discourse of creating an image of indigenous culture through the means of representing rural locale, language and customs in the works of R. K. Narayan and Pannalal Patel. The creative period of both the novelists extends from the pre-independence to the post-independence phase of the twentieth century India. Their works cover majority of features representing the postcolonial dimension of literature, which has been examined in the following chapters. Narayan is regarded as the father-figure in postcolonial Indian English fiction. Similarly Pannalal Patel’s creativity writing too has a comparable place. Both represent the notion of region and nation which has become now-a-days vigorous debate in postcolonial studies. The thesis explores how the literary discourse of their novels participates in constructing ‘nation’ in a postcolonial context by representing ‘region’. Instead of seeing the categories of ‘nation’ and ‘region’ as simple opposites, the thesis examines the problematic ways in which these notions are represented. -

Movies of Feroz Khan

1 / 2 Movies Of Feroz Khan Feroze Khan (born July 11, 1990) is famous for being tv actor. ... Padmavati is undeniably the most awaited movie of the year and it won't be hard to call it a hit .... Feroz Khan Movies List. Thambi Arjuna (2010)Ramana, Aashima. Welcome (2007)Feroz Khan, Anil Kapoor. Ek Khiladi Ek Haseena (2005)Fardeen Khan, .... See more ideas about actors, pakistani actress, feroz khan. ... Khushbo is Pakistani film and stage Actress. c) On some minimal productions (e. Want to Become .... Tasveer Full Hindi Movie (1966) Film cast : Feroz Khan, Kalpana, Helen, Sajjan, Rajendra Nath, Nazir Hasain, Leela Mishra, Raj Mehra, Lalita Pawar, Sabeena. MUMBAI, India (Agence France-Presse) — Feroz Khan, a Bollywood ... he made “Dharmatma,” the first Hindi-language movie shot on location .... Actor Rishi Kapoor tweeted that the two actors, who worked together in three films, died of Cancer on the same date. Known for his flamboyant persona, Feroz Khan was an actor, director and producer who had a long innings in the Hindi film industry. The actor .... Feroz Khan was born at Bangalore in India to an Afghan Father, Sadiq Khan and an Iranian mother Fatima. After schooling from Bangalore he shifted to Bombay .... He would have turned 79 on September 25. However, actor, director and producer Feroz Khan – one of his kind in the Hindi film industry .... Feroz Khan All Movies List · Ek Khiladi Ek Haseena - 2005 · Ek Khiladi Ek Haseena (2005)Feroz Khan , Fardeen Khan , Koena Mitra , Gulshan Grover , Kay Kay , .... India's answer to Clint Eastwood, Feroz Khan is known as the most stylish bollywood actor. -

Breath Becoming a Word

BREATH BECOMING A WORD CONTMPORARY GUJARATI POETRY IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION EDITED BY DILEEP JHAVERI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My earnest thanks to GUJARAT SAHITYA AKADEMI for publishing this book and to Harshad Trivedi. With his wholehearted support a dream is fulfilled. Several of these translations have appeared in INDIAN LITERATURE- Sahitya Akademi Delhi MUSEINDIA KRITYA- web journals and elsewhere. Thanks to all of them. Cover page painting by Late Jagdeep Smart with the kind permission of Smt Nita Smart and Rajarshi Smart Dedicated to PROF. K. SATCHIDANANDAN The eminent poet of Malayalam who has continuously inspired other Indian languages while becoming a sanctuary for the survival of Poetry. BREATH BECOMING A WORD It’s more than being in love, boy, though your ringing voice may have flung your dumb mouth thus: learn to forget those fleeting ecstasies. Far other is breath of real singing. An aimless breath. A stirring in the god. A breeze. Rainer Maria Rilke From Sonnets To Orpheus This is to celebrate the breath becoming a word and the joy of word turning into poetry. This is to welcome the lovers of poetry in other languages to participate in the festival of contemporary Gujarati poetry. Besides the poets included in this selection there are many who have contributed to the survival of Gujarati poetry and there are many other poems of the poets in this edition that need to be translated. So this is also an invitation to the friends who are capable to take over and add foliage and florescence to the growing garden of Gujarati poetry. Let more worthy individuals undertake the responsibility to nurture it with their taste and ability. -

Université De Montréal /7 //F Ç /1 L7iq/5-( Dancing Heroines: Sexual Respectability in the Hindi Cinema Ofthe 1990S Par Tania

/7 //f Ç /1 l7Iq/5-( Université de Montréal Dancing Heroines: Sexual Respectability in the Hindi Cinema ofthe 1990s par Tania Ahmad Département d’anthropologie Faculté des arts et sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l’obtention du grade de M.Sc. en programme de la maîtrise août 2003 © Tania Ahrnad 2003 n q Université (1111 de Montréal Direction des bibliothèques AVIS L’auteur a autorisé l’Université de Montréal à reproduire et diffuser, en totalité ou en partie, par quelque moyen que ce soit et sur quelque support que ce soit, et exclusivement à des fins non lucratives d’enseignement et de recherche, des copies de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse. L’auteur et les coauteurs le cas échéant conservent la propriété du droit d’auteur et des droits moraux qui protègent ce document. Ni la thèse ou le mémoire, ni des extraits substantiels de ce document, ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement reproduits sans l’autorisation de l’auteur. Afin de se conformer à la Loi canadienne sur la protection des renseignements personnels, quelques formulaires secondaires, coordonnées ou signatures intégrées au texte ont pu être enlevés de ce document. Bien que cela ait pu affecter la pagination, il n’y a aucun contenu manquant. NOTICE The author of this thesis or dissertation has granted a nonexclusive license allowing Université de Montréal to reproduce and publish the document, in part or in whole, and in any format, solely for noncommercial educational and research purposes. The author and co-authors if applicable retain copyright ownership and moral rights in this document.