Saints, Icons, and Relics Fr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mariology – Part 2

PAUL M. WILLIAMS [09/12/16] IS ROMAN CATHOLICISM TRUE CHRISTIANITY? – PART 11 MARIOLOGY – PART 2 Recap We began in our last teaching part to explore what is termed in the realm of theology, Mariology – which is the study of Mary, the mother of Jesus. We outlined the biblical portrayal of Mary, a righteous women and a humble handmaid of the Lord. She it was who was found with child of the Holy Spirit, who gave birth to Messiah and nursed Him who was called King of the Jews. We looked at the early life of Jesus and how His mother played an integral role in His nativity and in His early childhood. However, we also saw that as Jesus was growing into manhood, a clear transitioning of authority was taking place between that of His submission to his earthly parents and His submission to His Father in heaven. This was brought out most forcefully in two accounts recorded in the gospel of Luke and John – the first being Jesus’ response to Mary when being only twelve in Jerusalem (Luke 2:48-49) and the other when just beginning His ministry at the wedding in Cana of Galilee (John 2:1-5). For Roman Catholics, Mary is not merely and only the biological mother of Jesus, the vehicle used by God to bring His Son into this world. Official Catholic Church dogma teaches that Mary remained a perpetual virgin; that Mary is free from original sin (Immaculate Conception) and at the end of her life on earth, she was taken up into heaven where she continues perpetually to be the mother of God and Queen of Heaven. -

Naples, 1781-1785 New Evidence of Queenship at Court

QUEENSHIP AND POWER THE DIARY OF QUEEN MARIA CAROLINA OF NAPLES, 1781-1785 New Evidence of Queenship at Court Cinzia Recca Queenship and Power Series Editors Charles Beem University of North Carolina, Pembroke Pembroke , USA Carole Levin University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln , USA Aims of the Series This series focuses on works specializing in gender analysis, women's studies, literary interpretation, and cultural, political, constitutional, and diplomatic history. It aims to broaden our understanding of the strategies that queens-both consorts and regnants, as well as female regents-pursued in order to wield political power within the structures of male-dominant societies. The works describe queenship in Europe as well as many other parts of the world, including East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Islamic civilization. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14523 Cinzia Recca The Diary of Queen Maria Carolina of Naples, 1781–1785 New Evidence of Queenship at Court Cinzia Recca University of Catania Catania , Italy Queenship and Power ISBN 978-3-319-31986-5 ISBN 978-3-319-31987-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-31987-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947974 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Dogmatic Canons and Decrees

;ru slsi, \ DOGMATIC CANONS AND DECREES AUTHORIZED TRANSLATIONS OF THE DOGMATIC DECREES OF THE COUNCIL OF TRENT, THE DECREE ON THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION, THE SYLLABUS OF POPE PIUS IX, AND THE DECREES OF THE VATICAN COUNCIL * NEW YORK THE DEVIN-ADAIR COMPANY 1912 REMIGIUS LAFORT, D.D. Censor imprimatur )J<JOHN CARDINAL FARLEY Archbishop of New York June 22, 1912 COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY THE DEVIN-ADAIR COMPANY PREFACE versions of recent ecclesias ENGLISHtical decrees are easily found in pamphlet, book, or periodical. Up to the present time, however, this has not been true of earlier decrees. Those of Trent, bearing on justification, grace, the sacraments, etc., have long been out of print; so also the decree on the Immaculate Conception and the Syllabus of Pope Pius IX. It has seemed advisable, therefore, to publish in one volume, a collection of the most important dogmatic decrees from the Council of Trent down to the reign of Pope Leo XIII. No one will fail to recognize the desirability of such a collection. In almost every doc trinal treatise or sermon some of these decrees are sure to be used. In the majority of cases the writer or preacher is unable to quote directly, because in matters so important he naturally shrinks from the responsibility of giving an exact English rendering of the PREFACE original Latin. With an approved transla tion to guide him he will now be able to quote directly, and thus to state and explain the doctrines of the Church in her own words. In the present volume we have used Canon Waterworth s translation for the Council of Trent; Cardinal Manning s for the Vatican Council; and for the Syllabus, the one author ized by Cardinal McCabe, Archbishop of Dublin. -

St.-Thomas-Aquinas-The-Summa-Contra-Gentiles.Pdf

The Catholic Primer’s Reference Series: OF GOD AND HIS CREATURES An Annotated Translation (With some Abridgement) of the SUMMA CONTRA GENTILES Of ST. THOMAS AQUINAS By JOSEPH RICKABY, S.J., Caution regarding printing: This document is over 721 pages in length, depending upon individual printer settings. The Catholic Primer Copyright Notice The contents of Of God and His Creatures: An Annotated Translation of The Summa Contra Gentiles of St Thomas Aquinas is in the public domain. However, this electronic version is copyrighted. © The Catholic Primer, 2005. All Rights Reserved. This electronic version may be distributed free of charge provided that the contents are not altered and this copyright notice is included with the distributed copy, provided that the following conditions are adhered to. This electronic document may not be offered in connection with any other document, product, promotion or other item that is sold, exchange for compensation of any type or manner, or used as a gift for contributions, including charitable contributions without the express consent of The Catholic Primer. Notwithstanding the preceding, if this product is transferred on CD-ROM, DVD, or other similar storage media, the transferor may charge for the cost of the media, reasonable shipping expenses, and may request, but not demand, an additional donation not to exceed US$25. Questions concerning this limited license should be directed to [email protected] . This document may not be distributed in print form without the prior consent of The Catholic Primer. Adobe®, Acrobat®, and Acrobat® Reader® are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. -

Copy of Holy Eucharist

HOLY EUCHARIST WHEN DID JESUS CHRIST INSTITUTE THE EUCHARIST? Jesus instituted the Eucharist on Holy Thursday “the night on which he was betrayed” (1 Corinthians 11:23), as he celebrated the Last Supper with his apostles. WHAT DOES THE EUCHARIST REPRESENT IN THE LIFE OF THE CHURCH? It is the source and summit of all Christian life. In the Eucharist, the sanctifying action of God in our regard and our worship of him reach their high point. It contains the whole spiritual good of the Church, Christ himself, our Pasch. Communion with divine life and the unity of the People of God are both expressed and effected by the Eucharist. Through the Eucharistic celebration we are united already with the liturgy of heaven and we have a foretaste of eternal life. WHAT ARE THE NAMES FOR THIS SACRAMENT? The unfathomable richness of this sacrament is expressed in different names which evoke its various aspects. The most common names are: the Eucharist, Holy Mass, the Lord’s Supper, the Breaking of the Bread, the Eucharistic Celebration, the Memorial of the passion, death and Resurrection of the Lord, the Holy Sacrifice, the Holy and Divine Liturgy, the Sacred Mysteries, the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar, and Holy Communion. HOW IS THE CELEBRATION OF THE HOLY EUCHARIST CARRIED OUT? The Eucharist unfolds in two great parts which together form one, single act of worship. The Liturgy of the Word involves proclaiming and listening to the Word of God. The Liturgy of the Eucharist includes the presentation of the bread and wine, the prayer or the anaphora containing the words of consecration, and communion. -

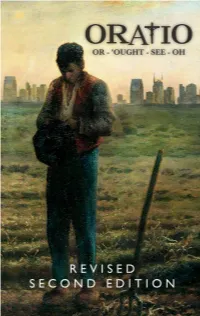

Oratio-Sample.Pdf

REVISED SECOND EDITION RHYTHMS OF PRAYER FROM THE HEART OF THE CHURCH DILLON E. BARKER JIMMY MITCHELL EDITORS ORATIO (REVISED SECOND EDITION) © 2017 Dillon E. Barker & Jimmy Mitchell. First edition © 2011. Second edition © 2014. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-692-89224-4 Published by Mysterium LLC Nashville, Tennessee, U.S.A. LoveGoodCulture.com NIHIL OBSTAT: Rev. Jayd D. Neely Censor Librorum IMPRIMATUR: Most Rev. David R. Choby Bishop of Nashville May 9, 2017 For bulk orders or group rates, email [email protected]. Special thanks to Jacob Green and David Lee for their contributions to this edition. Excerpts taken from Handbook of Prayers (6th American edition) Edited by the Rev. James Socias © 2007, the Rev. James Socias Psalms reprinted from The Psalms: A New Translation © 1963, The Grail, England, GIA Publications, Inc., exclusive North American agent, www.giamusic.com. All rights reserved. Excerpts from the Revised Standard Version Bible, Second Catholic Edition © 2000 & 2006 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Excerpts from the English translation of The Roman Missal © 2010, USCCB & ICEL; excerpts from the Rites of the Catholic Church © 1990, USCCB & ICEL; excerpts from the Book of Blessings © 1988, 1990, USCCB & ICEL. All rights reserved. All ritual texts of the Catholic Church not already mentioned are © USCCB & ICEL. Cover art & design by Adam Lindenau adapted from “The Angelus” by Jean-François Millet, 1857 The Tradition of the Church proposes to the faithful certain rhythms of praying intended to nourish continual prayer. Some are daily, such as morning and evening prayer, grace before and after meals, the Liturgy of the Hours. -

Saints and Angels (Tuesday)

LITANY & DEVOTIONS to Angels & Saints Tuesday 1pm Devotion Angels and Saints The celebrant leads the two opening prayers to Angels, one of the two versions of the Litany of Saints and choses one or more of the other prayers and then gives a blessing. Celebrant (to camera) We call upon our heavenly Father and Jesus His divine Son to send the Holy Spirit of healing upon our world at this time of pandemic. We ask the Angels to watch over, guard and protect us, especially, all our doctors, nurses, health-care workers and caregivers; may they be safe as our frontline against this pestilence, and may the angels strengthen and guide all essential and other emergency services We call upon the holy Saints in heaven, our elder and brothers and sisters, who have gone before us marked with the sign of faith, to intercede for us, for mercy, hope and healing, for those who are suffering from Covid 19 and to welcome in to the halls of heaven those who have died. Opening Prayers (2) face altar standing 1 To our Guardian Angel Angel of God, my guardian dear, to whom God's love commits me here, ever this day be at my side, to light and guard, to rule and guide. Amen. 2 Prayer for the Archangels to protect us from Covid19 Heavenly Father, you have given us archangels to accompany us on our pilgrimage on earth. Hear and answer our prayers and pour upon us your grace and compassion. Send Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, to be with us today as we confront this terrible coronavirus. -

Guidelines for Eucharistic Processions

Guidelines for Eucharistic Processions Pope Paul VI writes of special forms of worship of the Eucharist, “The Catholic Church has always displayed and still displays this latria that ought to be paid to the Sacrament of the Eucharist, both during Mass and outside of it, by taking the greatest possible care of consecrated hosts, by exposing them to the solemn veneration of the faithful, and by carrying them about in processions to the joy of great numbers of the people.”1 May our processions also bring joy to all who participate! This is not an unfounded joy, but one founded on the knowledge that Christ comes to us, to be among us, to make is dwelling in our midst, to teach us, and lead us to the Father. The following are helpful guidelines for preparing a Eucharistic Procession according to the norms of the Church. 1. The source texts for Eucharistic Processions is Holy Communion and Worship of the Eucharist Outside Mass (HCWEOM), #’s 101-108 and Ceremonial of Bishops #’s 385-394. 2. The following are the things that should be prepared for the procession in addition to what is needed for the Mass: a. A host to be used in the monstrance b. Monstrance c. Humeral Veil d. [Second Thurible] e. Candles for the procession f. [Canopy] 3. A day of especial importance for Eucharistic devotion, and thus also for processions, is the Feast of Corpus Christi. While processions may be done on other days, it is for the local ordinary to determine these other times (cf. HCWEOM 101-102) 4. -

The Martyrologies and Calendars the Heretics Produced in England

Book 2, chapter 37 The Martyrologies and Calendars the Heretics Produced in England The devil is the ape of God, seeking to usurp the honor and glory due the divine majesty in every way he can: in shrines, altars, sacrifices, offerings, and all that pertains to sacred worship, and to that highest reverence (called latria) owed to God alone,1 the evil one has tried to imitate God, that he might be acknowledged and served as God, deceiving countless men and instructing them to adore stone, and clay, and silver, and gold, and the gods and works of their hands,2 and him therein, as he did in ancient times, and as the blind pagans do even in our own day. In the same way, the heretics, the sons of the demon,3 little vipers who emerge from the entrails of a viper, strive to be apes of the Catholics—neither in faith nor in sanctity, but only in usurping the honor owed to them, mimicking in their hypocritical synagogues what the Catholic Church represents in the congregation of the faithful. For this reason, seeing that the Catholic Church has its saints and martyrs, which it reveres as such and honors on their days, to the glory of the saints and the imitation and emulation of their deeds, the heretics have chosen to celebrate as saints and regard as martyrs those heretics who have been justly burned, whether for their crimes or4 in the name of our faith. The Arian Bishop Georgius died for his crimes in Alexandria, and was venerated and honored as a martyr by the other Arian heretics, as Ammianus Marcellinus says;5 the Donatist Salvius was killed by other heretics—likewise Donatists, but of another, contrary sect— and those of his sect built a temple to him, and esteemed and revered him as martyr, as Saint Augustine writes.6 And so, following the example of their 1 Beginning with Augustine, theologians had distinguished between latria, the worship due only to God, and dulia, the reverence that might be accorded the saints. -

Litany of the Saints Leader: Lord, Have Mercy on Us

Litany of the Saints Leader: Lord, have mercy on us. All: Christ, have mercy on us. Leader: Lord, have mercy on us. Leader: All: Christ hear us. Christ, graciously hear us. God the Father of Heaven... Have mercy on us. God the Son, Redeemer of the world... Have mercy on us. God the Holy Spirit... Have mercy on us. Holy Trinity, one God... Have mercy on us. Holy Mary, Mother of God… Pray for us. Saint Agnes… Saint Michael, the Archangel… Saint Gregory… Holy Angels of God… Saint Augustine… Saint John the Baptist… Saint Athanasius… Saint Joseph… Saint Basil… Saint Peter and Saint Paul… Saint Martin… Saint Andrew… Saint Benedict… Saint John… Saint Francis and Saint Dominic… Saint Mary Magdalene… Saint Francis Xavier… Saint Stephen… Saint John Vianney… Saint Ignatius… Saint Catherine… Saint Lawrence… Saint Teresa… Saint Perpetua and Saint Felicity… All holy men and women… St. Dominic receiving the Rosary, 19th century lithograph From all evil… O Lord, deliver us. Through the mystery of Thy holy Incarnation… From all sin… Through Thy coming… From Thy wrath… Through Thy nativity… From a sudden and unprovided death… Through Thy baptism and holy fasting… From the snares of the devil… Through Thy cross and Passion… From anger, and hatred, and all ill will… Through Thy death and burial… From the spirit of fornication… Through Thy holy Resurrection… From lightning and tempest… Through Thine admirable Ascension… From the scourge of earthquake… Through the coming of the Holy Spirit… From pestilence, famine and war… In the Day of Judgment… From everlasting death… Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.. -

Pastor's Office

FR. VICTOR HERNANDO Pastor/Administrator Email: [email protected] OLS Phone: (559) 642-3452 From the Pastor’s Office My Dear Friends: The month of November has so many important feast days of the Church! To me it is important to know what these feast days mean. For this reason, I have included in this publication articles about All Saints Day (page 2) and All Souls Day (page 3). Please take time to read them, then spend some time in prayer, attending Mass (livestream or outdoors) and offering your special prayers and intentions on these days. Note the schedule of Masses below: SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES FOR NOVEMBER OCTOBER 31, SATURDAY: VIGIL MASS FOR ALL SAINTS DAY AT OLS 3:00–4:00 PM: Confessions 3:30 PM Rosary with Litany of the Saints 4:00 PM Mass After Mass blessing of water for visit to the cemetery NOVEMBER 01, SUNDAY: MASS FOR ALL SAINTS DAY 8:00 AM St. Joseph the Worker 9:30 AM St. Dominic Savio 11:30 AM Our Lady of the Sierra All masses are preceded by: Rosary with Litany of the Saints Prayers for the Dead Bless water to be used when you go to the cemetery. Prayers for the visit to the cemetery will be distributed. NOVEMBER 02, MONDAY: ALL SOULS DAY AT OLS 9:00 AM Rosary – Litany of the Poor Souls in Purgatory Mass October 28, 2020 Objectives of The Feast Today, we thank God for giving ordinary men and women a share in His holiness and Heavenly glory as a reward for their Faith. -

Saint Augustine of Hippo Catholic Church

The Holy Family of Jesus, Mary and Joseph December 27, 2020 Saint Augustine of Hippo Catholic Church 2530 South Howell Avenue • Milwaukee, WI 53207 Sacraments of Initiation Infant Baptism Baptism is celebrated regularly throughout the year. Contact the parish office for further information. Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults Adults wishing to come into full communion with the church, should contact the Director of RCIA for information regarding classes of preparation. Adult Confirmation Schedule of Masses Post-High School adults 18 years and older who wish to receive the Sacrament of Weekends: Confirmation are asked to participate in the Inter-parish Collaborative Process beginning Saturday Daily 8:30am each Fall. Contact the Director of Adult Confirmation for information. Saturday Vigil 4:00pm (Suspended UFN) Sunday 11:00am Sacrament of Marriage All couples wishing to celebrate the Sacrament of Marriage at St. Augustine Weekdays: must be members of the parish for at least one year prior to the date of the Tuesday & Thursday at 8:30am wedding. Contact the Pastor and the Director of Worship a minimum of six Holydays: As scheduled in the bulletin. months in advance of your intended wedding date. Sacrament of Reconciliation Saturday 9:00am to 10:00am Anointing of the Sick & Communion to the Sick/Shut-In Parish Office Hours .... Monday - Friday 8:00am - 4:30pm Phone ..................................... 414-744-0808 Parish Membership Parish Email ............. [email protected] Families and Single Persons 18 years and older are asked to register at the Website .............................. www.staugies.org Parish in order to receive services the Church offers to all members of our parish Religious Ed www.southeastcatholic.org family.