Notes and References

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 007Th Minute Ebook Edition

“What a load of crap. Next time, mate, keep your drug tripping private.” JACQUES A person on Facebook. STEWART “What utter drivel” Another person on Facebook. “I may be in the minority here, but I find these editorial pieces to be completely unreadable garbage.” Guess where that one came from. “No, you’re not. Honestly, I think of this the same Bond thinks of his obituary by M.” Chap above’s made a chum. This might be what Facebook is for. That’s rather lovely. Isn’t the internet super? “I don’t get it either and I don’t have the guts to say it because I fear their rhetoric or they’d might just ignore me. After reading one of these I feel like I’ve walked in on a Specter round table meeting of which I do not belong. I suppose I’m less a Bond fan because I haven’t read all the novels. I just figured these were for the fans who’ve read all the novels including the continuation ones, fan’s of literary Bond instead of the films. They leave me wondering if I can even read or if I even have a grasp of the language itself.” No comment. This ebook is not for sale but only available as a free download at Commanderbond.net. If you downloaded this ebook and want to give something in return, please make a donation to UNICEF, or any other cause of your personal choice. BOOK Trespassers will be masticated. Fnarr. BOOK a commanderbond.net ebook COMMANDERBOND.NET BROUGHT TO YOU BY COMMANDERBOND.NET a commanderbond.net book Jacques I. -

Copyright in Teams Anthony J

Copyright in Teams Anthony J. Caseyt & Andres Sawickitt Dozens of people worked together to produce Casablanca. But a single person working alone wrote The Sound and the Fury. While almost all films are produced by large collaborations,no great novel ever resulted from the work of a team. Why does the frequency and success of collaborative creative production vary across art forms? The answer lies in significantpart at the intersection of intellectualproperty law and the theory of the firm. Existing analyses in this area often focus on patent law and look almost exclusively to a property-rights theory of the firm. The impli- cations of organizational theory for collaborative creativity and its intersection with copyright law have been less examined. To fill this gap, we look to team- production and moral-hazardtheories to understandhow copyright law can facili- tate or impede collaborative creative production. While existing legal theories look only at how creative goods are integrated with complementary assets, we explore how the creative goods themselves are produced. This analysis sheds new light on poorly understood features of copyright law, including the derivative-works right, the ownership structure ofa joint work, and the work-made-for-hire doctrine. INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 1684 I. A THEORY OF CREATIVE PRODUCTION ........................... 1690 A. The Limitations of Property-Rights Theory ..................... 1690 B. Theories of Team Production. .................... .......... 1694 1. The monitoring manager ........................ 1695 t Assistant Professor of Law, The University of Chicago Law School. The Jerome F. Kutak Faculty Fund provided research support. ft Associate Professor of Law, University of Miami School of Law. This article is built largely on foundational theories pioneered by the late Ronald H. -

Legends of Screenwriting “Richard Maibaum” by Ray Morton

Legends of Screenwriting “Richard Maibaum” By Ray Morton Screenwriters are generally a cerebral lot and not usually thought of as men (or women) of action, but Richard Maibaum certainly was, especially when it comes to writing about the adventures of a certain British secret agent with a triple digit code name and a license to kill. Maibaum was born on May 26, 1909 in New York City. He attended New York University and the University of Iowa and then became an actor on Broadway. In 1930 he began writing plays, including 1932’s The Tree, 1933’s Birthright, 1935’s Sweet Mystery of Life (with Michael Wallach and George Haight) and 1939’s See My Lawyer (with Harry Clark). When MGM bought the rights to Sweet Mystery of Life to use as the basis for its 1936 film Gold Diggers of 1937 (screenplay by Warren Duff), the studio also signed Maibaum, who moved to Hollywood and began writing for the movies. Between 1936 and 1942 he wrote or co-wrote scripts for MGM, Columbia, Twentieth Century- Fox, and Paramount, including We Went to College (1936), The Bad Man of Brimstone (1937), The Lady and the Mob (1939), 20 Mule Team (1940), I Wanted Wings (1941), and Ten Gentlemen from West Point (1942). After the United States entered World War II, Richard spent several years in the Army’s Combat Film Division. Following the war, Maibaum became a writer/producer at Paramount, where he wrote his first spy movie— O.S.S. (1946), which was based on files and research provided by the actual Office of Strategic Services. -

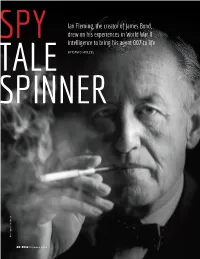

Ian Fleming, the Creator of James Bond, Drew on His Experiences In

Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, SPY drew on his experiences in World War II intelligence to bring his agent 007 to life TALE BY DAVID HOLZEL SPINNER Horst Tappe / Contributor Tappe Horst 20 BOSS 4 s u mm e r 2016 erman U-boats were infesting the Child of Privilege waters of the Caribbean in July G 1943 when high-level American Ian Lancaster Fleming was born and British naval intelligence agents met in London on May 28, 1908, into in the British colonial outpost of wealth, although it was new wealth. Jamaica to jaw out a response. His paternal grandfather had made e head of the British team, a fortune trading railroad stocks. 35-year-old Ian Fleming, was the e family of his mother, Eve, had charming personal assistant to the chief begun humbly, but her grandfathers of naval intelligence. At the end of each had risen in their professions and had day of meetings, Fleming and his British been knighted. colleague and friend Ivar Bryce escaped Ian and his three brothers were the humidity of Kingston to an old children of privilege. eir father, Valentine Fleming, was a Conservative manor house on the mountainside USA/ZUMAPRESS/Newscom Pictures KEYSTONE above the city. ere they sat on the member of parliament and a friend balcony, drinking grenadine and of Winston Churchill. When World looking out at the tropical rain. War I broke out in 1914, Valentine Reuters in London, which led to trips to Aer the conference, on the volunteered to ght. He was killed in Berlin and Moscow. -

Against Expression an Anthology of Conceptual Writing

Against Expression Against Expression An Anthology of Conceptual Writing E D I T E D B Y C R A I G D W O R K I N A N D KENNETH GOLDSMITH Northwestern University Press Evanston Illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © by Northwestern University Press. Published . All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America + e editors and the publisher have made every reasonable eff ort to contact the copyright holders to obtain permission to use the material reprinted in this book. Acknowledgments are printed starting on page . Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Against expression : an anthology of conceptual writing / edited by Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith. p. cm. — (Avant- garde and modernism collection) Includes bibliographical references. ---- (pbk. : alk. paper) . Literature, Experimental. Literature, Modern—th century. Literature, Modern—st century. Experimental poetry. Conceptual art. I. Dworkin, Craig Douglas. II. Goldsmith, Kenneth. .A .—dc o + e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, .-. To Marjorie Perlo! Contents Why Conceptual Writing? Why Now? xvii Kenneth Goldsmith + e Fate of Echo, xxiii Craig Dworkin Monica Aasprong, from Soldatmarkedet Walter Abish, from Skin Deep Vito Acconci, from Contacts/ Contexts (Frame of Reference): Ten Pages of Reading Roget’s ! esaurus from Removal, Move (Line of Evidence): + e Grid Locations of Streets, Alphabetized, Hagstrom’s Maps of the Five Boroughs: . Manhattan Kathy Acker, from Great Expectations Sally Alatalo, from Unforeseen Alliances Paal Bjelke Andersen, from + e Grefsen Address Anonymous, Eroticism David Antin, A List of the Delusions of the Insane: What + ey Are Afraid Of from Novel Poem from + e Separation Meditations Louis Aragon, Suicide Nathan Austin, from Survey Says! J. -

Entertainment Memorabilia Entertainment

Montpelier Street, London I 12 June 2019 Montpelier Street, Entertainment Memorabilia Entertainment Entertainment Memorabilia I Montpelier Street, London I 12 June 2019 25431 Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams International Board Registered No. 4326560 Malcolm Barber Co-Chairman, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Montpelier Street, London SW7 1HH Matthew Girling CEO, Asaph Hyman, Caroline Oliphant, +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 Edward Wilkinson, Geoffrey Davies, James Knight, +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax Jon Baddeley, Jonathan Fairhurst, Leslie Wright, Rupert Banner, Simon Cottle. Lot 13 Entertainment Memorabilia Montpelier Street, London | Wednesday 12 June 2019 at 1pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES The following symbol is used to denote that VAT is due on SPECIAL NOTICE TO Montpelier Street Claire Tole-Moir BUYERS Knightsbridge, +44 (0) 20 7393 3984 the hammer price and buyer’s Given the age of some of London SW7 1HH [email protected] premium the Lots they may have been www.bonhams.com damaged and/or repaired and Stephen Maycock † VAT 20% on hammer price you should not assume that +44 (0) 20 7393 3844 and buyer’s premium VIEWING a Lot is in good condition. [email protected] Sunday 9 June * VAT on imported items at Electronic or mechanical parts 11am to 3pm may not operate or may not Aimee Clark a preferential rate of 5% on Monday 10 June comply with current statutory +44 (0) 20 7393 3871 hammer price and the prevailing 9am to 4.30pm requirements. You should not [email protected] rate on buyer’s premium Tuesday 11 June assume that electical items 9am to 4.30pm Y These lots are subject to designed to operate on mains SALE NUMBER: Wednesday 12 June CITES regulations, please read electricity will be suitable 9am to 11am 25431 the information in the back of the for connection to the mains catalogue. -

Against Expression: an Anthology of Conceptual Writing

Against Expression Against Expression An Anthology of Conceptual Writing E D I T E D B Y C R A I G D W O R K I N A N D KENNETH GOLDSMITH Northwestern University Press Evanston Illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © by Northwestern University Press. Published . All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America + e editors and the publisher have made every reasonable eff ort to contact the copyright holders to obtain permission to use the material reprinted in this book. Acknowledgments are printed starting on page . Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Against expression : an anthology of conceptual writing / edited by Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith. p. cm. — (Avant- garde and modernism collection) Includes bibliographical references. ---- (pbk. : alk. paper) . Literature, Experimental. Literature, Modern—th century. Literature, Modern—st century. Experimental poetry. Conceptual art. I. Dworkin, Craig Douglas. II. Goldsmith, Kenneth. .A .—dc o + e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, .-. To Marjorie Perlo! Contents Why Conceptual Writing? Why Now? xvii Kenneth Goldsmith + e Fate of Echo, xxiii Craig Dworkin Monica Aasprong, from Soldatmarkedet Walter Abish, from Skin Deep Vito Acconci, from Contacts/ Contexts (Frame of Reference): Ten Pages of Reading Roget’s ! esaurus from Removal, Move (Line of Evidence): + e Grid Locations of Streets, Alphabetized, Hagstrom’s Maps of the Five Boroughs: . Manhattan Kathy Acker, from Great Expectations Sally Alatalo, from Unforeseen Alliances Paal Bjelke Andersen, from + e Grefsen Address Anonymous, Eroticism David Antin, A List of the Delusions of the Insane: What + ey Are Afraid Of from Novel Poem from + e Separation Meditations Louis Aragon, Suicide Nathan Austin, from Survey Says! J. -

The James Bond Phenomenon

CTCS 469 THE JAMES BOND PHENOMENON SPRING 2013 INSTRUCTOR: Dr. Rick Jewell, Hugh M. Hefner Professor of American Film OFFICE: George Lucas Bldg., SCA 303; [email protected] TEACHING ASSISTANTS: Luci Marzola ([email protected]) RJ Ashmore ([email protected]) Nicholas Emme ([email protected]) 1. COURSE DESCRIPTION: CTCS 469 will focus on a number of issues that pivot around the extraordinary longevity of the James Bond films. These issues will include literary source material and adaptation strategies, business practices, genre influences, cultural context, narrative and style, representation, mythology, ideology and stardom. 2. CLASS SESSIONS: Classes convene on Wednesday evenings at 6 in the Norris Cinema Theater. At least one film will be screened during each session. 3. TEXT BOOKS: Chapman, James. License to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films. Second edition. New York: I.B. Taurus, 2007. Lindner, Christopher (ed.). The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 2003. Five James Bond novels written by Ian Fleming: Casino Royale, Dr. No, From Russia With Love, Goldfinger, Thunderball 4. REQUIREMENTS: ONE TERM PAPER (12 page minimum) Due: April 10th (1/3 of final grade) MID-TERM EXAM March 6th (1/3 of final grade) FINAL EXAM May 8th, 7-9 p.m. (1/3 of final grade) 5. POLICIES: a. The MID-TERM and FINAL EXAM will cover lectures, screenings, assigned readings, handouts and discussions and will be primarily essay in nature. b. PENALTY SCHEDULE FOR LATE PAPERS: The final grade assigned to a late term paper will be lowered as follows: One day to one week: 1/3 letter grade One week to two weeks: One full letter grade Two weeks to three weeks: Two full letter grades More than three weeks: Paper receives a grade of F c. -

Peter Harrington London

Summer Miscellany Peter Harrington london 136 We are exhibiting at these fairs: 8–10 September 2017 brooklyn Brooklyn Antiquarian Book Fair Brooklyn Expo Center 79 Franklin St, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, NY www.brooklynbookfair.com 7–8 October pasadena Antiquarian Book, Print, Photo & Paper Fair Pasadena Center, Pasadena, CA www.bustamante-shows.com/book/index-book.asp 14–15 October seattle Seattle Antiquarian Book Fair Seattle Center Exhibition Hall www.seattlebookfair.com 3–5 November chelsea Chelsea Old Town Hall Kings Road, London SW3 www.chelseabookfair.com 10–12 November boston Boston International Antiquarian Book Fair Hynes Convention Center bostonbookfair.com 17–19 November hong kong China in Print Hong Kong Maritime Museum www.chinainprint.com VAT no. gb 701 5578 50 Front cover illustration by John Minton from Elizabeth David’s A Book of Mediterranean Food, item 68 Peter Harrington Limited. Registered office: WSM Services Limited, Connect House, Illustration above of Bullock’s Museum from John B. Papworth’s Select Views of London, item 162 133–137 Alexandra Road, Wimbledon, London SW19 7JY. Design: Nigel Bents; Photography Ruth Segarra Registered in England and Wales No: 3609982 Peter Harrington london catalogue 136 Summer Miscellany All items from this catalogue are on exhibition at Dover Street mayfair chelsea Peter Harrington Peter Harrington 43 Dover Street 100 Fulham Road London w1s 4ff London sw3 6hs uk 020 3763 3220 uk 020 7591 0220 eu 00 44 20 3763 3220 eu 00 44 7591 0220 usa 011 44 20 3763 3220 usa 011 44 7591 0220 Dover St opening hours: 10am–7pm Monday–Friday; 10am–6pm Saturday www.peterharrington.co.uk 1 1 ACKERMANN, Rudolph (publ.) The Mi- crocosm of London; or, London in Min- iature. -

And He Strikes Like THUNDERBALL!

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ...and he strikes like THUNDERBALL! “The trouble about writing something specially for a film is that I haven’t got a single idea in my head! Ian Fleming to Kevin McClory – 29th April 1959 Fresh on the heels of the announcement that Danjaq LLC, the producer of the James Bond films, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), the long-time distributor of the Bond films, have acquired all the rights and interests relating to James Bond from the estate and family of the late Kevin McClory, after legal and business disputes that have arisen periodically for over 50 years – December 18th 2013 will see the auction at Bonhams (Knightsbridge) of a number of unique and historically important items related to the labyrinthine story of the writing and subsequent film project that would eventually evolve into the fourth James Bond film Thunderball (1965) – the Biggest Bond of All! The legal battles began when James Bond creator Ian Fleming turned the first James Bond script, which he co-created in 1959 with Kevin McClory and respected British screenwriter Jack Whittingham, into the novel THUNDERBALL (1960) excluding the two men from any credit. In 1961, McClory (initially together with Whittingham) sued Fleming for plagiarism and after 10 days he won not only significant financial damages but also the film rights to THUNDERBALL. In 1965 in a strained collaboration with the established Bond producers Harry Saltzman and Albert R. ‘Cubby’ Broccoli, Kevin McClory produced the film Thunderball starring Sean Connery as James Bond 007, directed by Terence Young with the main title theme famously sung by Tom Jones. -

(1983) As 007'S Lesson in Adaptation Studies Traditi

Accepted manuscript version of: Schwanebeck, Wieland. “License to Replicate: Never Say Never Again (1983) as 007’s Lesson in Adaptation Studies.” James Bond Uncovered, edited by Jeremy Strong, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, pp. 163–84. Wieland Schwanebeck (Dresden) Licence to Replicate: Never Say Never Again (1983) as 007’s Lesson in Adaptation Studies Traditionally, the James Bond franchise existed outside the jurisdiction of adaptation studies, where the prestige of canonical literature frequently continues to overshadow the merits of film, especially popular blockbuster cinema. Though no-one working in adaptation studies would voice this attitude, the prevalent opinion still seems to be that cinema, as a ‘hot medium’ (Marshall McLuhan), “requires a less active response from the viewer” (Gjelsvik 256). Some go so far as to speak of a general “bias in favour of literature as both a privileged […] and an aesthetically sanctified field”, which may account for adaptation studies’s reputation as “fundamentally conservative” (Leitch 2008: 64f.) More recently, they have widened their focus and have gradually become more inclusive, investigating ‘lowbrow’ fiction and transmedial processes.1 Admittedly, this new inclusiveness entails certain dangers for the objects of their studies. Leaving popular franchises like James Bond out of adaptation studies certainly smacked of elitism and disdain, but it allowed them to retain a notable advantage which films that we more commonly perceive as literary adaptations don’t enjoy: they were treated as films in -

2001 Court Docket

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT DANJAQ LLC, a Delaware limited liability company; METRO- GOLDWYN-MAYER, INC., a Delaware corporation; UNITED ARTISTS CORPORATION, a Delaware corporation; UNITED ARTISTS PICTURES INC., a Delaware corporation; SEVENTEEN LEASING CORPORATION, a Delaware corporation; EIGHTEEN LEASING CORPORATION, a Delaware corporation; MGM/UA COMMUNICATIONS CO., No. 00-55781 Plaintiffs-Appellees, D.C. No. v. CV-97-08414-ER SONY CORPORATION, a Japanese OPINION corporation; SONY PICTURES ENTERTAINMENT, INC., a Delaware corporation; COLUMBIA PICTURES TELEVISION, INC., a Delaware corporation; JOHN CALLEY, an individual, Defendants, and KEVIN O'DONOVAN MCCLORY; SPECTRE ASSOCIATES, INC., an entity of unknown capacity, Defendants-Appellants. 11467 Appeal from the United States District Court for the Central District of California Edward Rafeedie, District Judge, Presiding Argued and Submitted May 11, 2001--Pasadena, California Filed August 27, 2001 Before: M. Margaret McKeown and Raymond C. Fisher, Circuit Judges, and David Warner Hagen,* District Judge. Opinion by Judge McKeown _________________________________________________________________ *Honorable David Warner Hagen, United States District Judge for the United States District Court for Nevada, sitting by designation. 11468 11469 11470 COUNSEL Kevin McClory, defendant-appellant, in propria persona. Paul J. Cohen, Segal, Cohen & Landis, Beverly Hills, Califor- nia, and Lucile Hotton Lynch, Carlsbad, California (argued), for defendant-appellant