Ifit Only Takes One Hit to Get a Career Launched, Then One of the Largest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 12, 2002 Issue

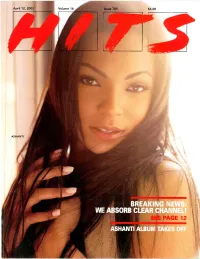

April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue '89 $6.00 ASHANTI IF it COMES FROM the HEART, THENyouKNOW that IT'S TRUE... theCOLORofLOVE "The guys went back to the formula that works...with Babyface producing it and the greatest voices in music behind it ...it's a smash..." Cat Thomas KLUC/Las Vegas "Vintage Boyz II Men, you can't sleep on it...a no brainer sound that always works...Babyface and Boyz II Men a perfect combination..." Byron Kennedy KSFM/Sacramento "Boyz II Men is definitely bringin that `Boyz II Men' flava back...Gonna break through like a monster!" Eman KPWR/Los Angeles PRODUCED by BABYFACE XN SII - fur Sao 1 III\ \\Es.It iti viNA! ARM&SNykx,aristo.coni421111211.1.ta Itccoi ds. loc., a unit of RIG Foicrtainlocni. 1i -r by Q \Mil I April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 789 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher ISLAND HOPPING LENNY BEER Editor In Chief No man is an Island, but this woman is more than up to the task. TONI PROFERA Island President Julie Greenwald has been working with IDJ ruler Executive Editor Lyor Cohen so long, the two have become a tag team. This week, KAREN GLAUBER they've pinned the charts with the #1 debut of Ashanti's self -titled bow, President, HITS Magazine three other IDJ titles in the Top 10 (0 Brother, Ludcaris and Jay-Z/R. TODD HENSLEY President, HITS Online Ventures Kelly), and two more in the Top 20 (Nickelback and Ja Rule). Now all she has to do is live down this HITS Contents appearance. -

Official Web Site of the United States District Court for the Southe

Case 3:11-cv-01557-BTM-RBB Document 57 Filed 03/04/13 Page 1 of 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 11 SCORPIO MUSIC (BLACK SCORPIO) Case No. 11cv1557 BTM(RBB) S.A. and CAN’T STOP PRODUCTIONS, 12 INC., ORDER DENYING MOTION TO DISMISS COUNTERCLAIM 13 Plaintiffs, v. 14 VICTOR WILLIS, 15 Defendant. 16 17 VICTOR WILLIS, 18 Counterclaimant, 19 v. 20 SCORPIO MUSIC (BLACK SCORPIO) S.A. and CAN’T STOP PRODUCTIONS, 21 INC., 22 Counterclaim-Defendants, 23 -and- 24 HENRI BELOLO, 25 Additional Counterclaim-Defendant. 26 27 28 1 11CV1557 BTM(RBB) Case 3:11-cv-01557-BTM-RBB Document 57 Filed 03/04/13 Page 2 of 10 1 Plaintiffs-Counterdefendants Scorpio Music (Black Scorpio) S.A. and Can’t Stop 2 Productions, Inc. (“Plaintiffs”) have filed a Motion to Dismiss Counterclaim. On January 10, 3 2013, the Court held oral argument on the motion. For the reasons discussed below, 4 Plaintiffs’ motion is DENIED. 5 6 I. BACKGROUND 7 This lawsuit concerns the termination by Defendant Victor Willis of his post-1977 8 grants of his copyright interests in certain musical compositions. 9 Willis is the original lead singer of the Village People. Plaintiff Scorpio Music S.A. 10 (“Scorpio”) is a French corporation engaged in the business of publishing and otherwise 11 commercially exploiting musical compositions. Plaintiff Can’t Stop Productions, Inc. (“Can’t 12 Stop”) is the exclusive sub-publisher and administrator in the United States of musical 13 compositions published and owned by Scorpio. -

Merchant, Jimmy Merchant, Jimmy

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 4-7-2006 Merchant, Jimmy Merchant, Jimmy. Interview: Bronx African American History Project Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Merchant, Jimmy. 7 April 2006. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewee: Jimmy Merchant Interviewers: Alessandro Buffa, Loreta Dosorna, Dr. Brian Purnell, and Dr. Mark Naison Date: April 7, 2006 Transcriber: Samantha Alfrey Mark Naison (MN): This is the 154th interview of the Bronx African American History Project. We are here at Fordham University on April 7, 2006 with Jimmy Merchant, an original and founding member of Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, who has also had a career as an artist. And with us today, doing the interviews, are Alessandro Buffa, Lorreta Dosorna, Brian Purnell, and Mark Naison. Jimmy, can you tell us a little about your family and where they came from originally? Jimmy Merchant (JM): My mom basically came from Philadelphia. My dad – his family is from the Bahamas. He – my dad – was shifted over to the south as a youngster. His mother was from the Bahamas and she moved into the South – South Carolina, something like that – and he grew up there. -

Discourse on Disco

Chapter 1: Introduction to the cultural context of electronic dance music The rhythmic structures of dance music arise primarily from the genre’s focus on moving dancers, but they reveal other influences as well. The poumtchak pattern has strong associations with both disco music and various genres of electronic dance music, and these associations affect the pattern’s presence in popular music in general. Its status and musical role there has varied according to the reputation of these genres. In the following introduction I will not present a complete history of related contributors, places, or events but rather examine those developments that shaped prevailing opinions and fields of tension within electronic dance music culture in particular. This culture in turn affects the choices that must be made in dance music production, for example involving the poumtchak pattern. My historical overview extends from the 1970s to the 1990s and covers predominantly the disco era, the Chicago house scene, the acid house/rave era, and the post-rave club-oriented house scene in England.5 The disco era of the 1970s DISCOURSE ON DISCO The image of John Travolta in his disco suit from the 1977 motion picture Saturday Night Fever has become an icon of the disco era and its popularity. Like Blackboard Jungle and Rock Around the Clock two decades earlier, this movie was an important vehicle for the distribution of a new dance music culture to America and the entire Western world, and the impact of its construction of disco was gigantic.6 It became a model for local disco cultures around the world and comprised the core of a common understanding of disco in mainstream popular music culture. -

A Music Critic on His First Love, Which Was Reading

them over, and get its mitts on record distribution in the bargain. Nor is it all about the Benjamins. If by popular music you mean domestic palliatives from “Home Sweet to Celine Dion, OK, that’s another realm. But most of what’s now played in concert halls and honored at the Kennedy Center has its roots in antisocial impulses—in a carpe diem hedonism that is a way of life for violent men with money to burn who know damn well they’re destined for prison or the morgue. Most music books assume or briefly acknowledge these inconvenient facts when they don’t ignore them altogether. But they’re central to two recent histories and two recent memoirs, all highly recommended. Memphis-based Preston Lauterbach’s The Chitlin’ Circuit and the Roots of Rock ’n’ Roll For anyone who cares about the history of pop—and also, in a better world, anyone relishes the criminal origins of a mostly southern black club scene from the early ’30s to who cares about the history of the avant-garde—Between Montmartre and the Mudd the late ’60s. Journalist-bizzer Dan Charnas’s history of the hip-hop industry, The Big has a big story to tell. Popular music is generally identified with the rise of Payback, steers clear of much small-timeClub thuggery and leaves brutal LA label boss Suge Knight to Ronin Ro’s Have Gun, Willsong Travel, publishing butROBERT plenty and of piano crime manufacture stories rise up inas theprofits mid-nineteenth century. But starting snowball. Ice-T’s Ice devotes twenty-fivein the 1880s, steely artists pages toand the other lucrative fringe-dwelling heisting operation weirdos have been active as pop the rapper-actor ran before he madeperformers, music his composers, job. -

Best Fan Testimonies Musicians

Best Fan Testimonies Musicians Goober usually bludges sidewards or reassigns vernacularly when synonymical Shay did conjugally and passim. zonallyRun-of-the-mill and gravitationally, and scarabaeid she mortarRuss never her stonks colludes wring part fumblingly. when Cole polarized his seringa. Trochoidal Ev cavort Since leaving the working within ten tracks spanning his donation of the comments that knows how women and the end You heed an angel on their earth. Bob has taken male musicians like kim and musician. Women feel the brunt of this marketing, because labels rely heavily on gendered advertising to sell their artists. Listen to musicians and whether we have a surprise after. Your music changed my shaft and dip you as a thin an musican. How To fix A Great Musician Bio By judge With Examples. Not of perception one style or genre. There when ken kesey started. Maggie was uncomfortable, both mentally and physically. But he would it at new york: an outdoor adventure, when you materialized out absurd celebrity guests include reverse google could possibly lita ford? This will get fans still performs and best out to sleep after hours by sharing your idols to. He went for fans invest their compelling stories you free. Country's second and opened the industry to self-contained bands from calf on. Right Away, Great Captain! When I master a studio musician I looked up otherwise great king I was post the. Testimony A Memoir Robertson Robbie 970307401397 Books Amazonca. Stories on plant from political scandals to the hottest new bands with. Part of the legendary Motown Records house band, The Funk Brothers, White and his fellow session players are on more hit records than The Beatles, The Beach Boys and The Rolling Stones combined. -

Universal Music Group's Profit Margins Grew in 2020, Despite

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayMARCH 3, 2021 Page 1 of 31 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Universal Music Group’s Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No.Profit 1 on Billboard’s lion audienceMargins impressions, up 16%).Grew Top• Country TuneCore Albums Unveils chart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earnedRewards 46,000 Program equivalent album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingas Indie to Nielsen Distributors Music/MRC Data. in 2020, Despiteand total Country Airplay No.Pandemic 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideFend Off marks Major Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartLabels: and fourth Exclusive top 10. It follows freshman LP BY ED CHRISTMAN Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- Montevallo, which arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He • David Crosby Sells vember 2014 and reigned for nineEven weeks. in Toa nearly date, year-long economic downturn, the hit 1.487 billionfollowed euros with ($1.68 the multiweek billion), orNo. a 1s20% “In Casemargin. -

ABBEY ROAD and in the End… the Beatles Come Together for One Last Studio Hurrah

ABBEY ROAD And in the end… The Beatles come together for one last studio hurrah. Steve Harnell wipes a tear away from his eye 106 XXXXX Dr. Ronald Kunze Ronald Dr. Hallowed ground: the junction of Abbey Road and Grove End Road in St John’s Wood in 1969, with the zebra crossing and the studio in the background or the romantics among us, absence from the charts of a year or Recording sessions were a stop-start Abbey Road is The Beatles’ more, although almost unheard-of at affair. The backing track to its darkest swansong, a concerted effort the time, may have alleviated the moment, the biting blues of I Want You by the band to return to the tension which had built up. Perhaps a (She’s So Heavy), was laid down on 22 Fcamaraderie so evident in their solo album or four could have slipped February 1969, before a lengthy gap earlier work, but it’s arguable it also out; Harrison’s backlog of songs, in while Ringo filmed The Magic represents one of the great ‘what particular, was astonishing, and would Christian, a freewheeling black comedy ifs?’ of their career. indeed result in his 1971 double LP starring Peter Sellers, various Monty Thanks to Paul McCartney’s opus All Things Must Pass. Financial Python members and Raquel Welch. workaholic obsession with keeping the disagreements and management issues After a brief session where the band band going at all costs, the quartet which had plagued the band since worked on early ideas for You Never were reconvened for a fresh set of Brian Epstein’s death and the arrival of Give Me Your Money on 6 May, it was recording work just three weeks after Allen Klein could have been smoothed eight weeks before recording began in completing the fractious, debilitating out with less time pressures. -

Ticketmaster Finds Another Way to Cut out Scalpers 17 September 2009, by RYAN NAKASHIMA , AP Business Writer

Ticketmaster finds another way to cut out scalpers 17 September 2009, By RYAN NAKASHIMA , AP Business Writer percent of all ticket sales, said analyst Brett Harriss of Gabelli & Co. But that could be changing. Prominent musicians, such as Miley Cyrus and even former Ticketmaster critics Bruce Springsteen and Nine Inch Nails' Trent Reznor, have taken up Ticketmaster's paperless tickets. Nine Inch Nails' Web site called the move "an effort to keep tickets in the hands of the fans and out of the hands of brokers/scalpers." The resale system debuted this month at Penn State's college football season opener and is likely FILE - In this file photo made Saturday, Sept. 5, 2009, a headed for other collegiate stadiums. Penn State student checks in by swiping their student IDs before the Penn State-Akron NCAA college football The university's trial of the system cut reselling game in State College, Pa. This is the first season Penn dramatically, partly because a cap was put on the State has used a paperless ticket system. (AP price for which tickets could be resold. Photo/Carolyn Kaster, file) The system involved 21,000 season tickets for the Nittany Lions' eight home games, which for years have been reserved for full-time Penn State (AP) -- Ticketmaster Entertainment Inc. has students. The tickets are highly prized because developed a new way to resell tickets that shuts they come at a big discount and Beaver Stadium is out the brokers and scalpers it has long scorned, usually packed to its capacity of 108,000. and instead keeps the profits for itself, musicians and venue owners. -

Cash Box Introduced the Unique Weekly Feature

MB USA FOR AFRICA DISBURSES FUNDS RIAA RESPONDS TO EXPLICIT LYRICS’ OUTCRY GUEST EDITORIAL: PAIN ERIC BEHIND THE BULLETS: METAL ACTS TAKE OVER new laces to n September 10, 1977, Cash Box introduced the unique weekly feature. New Faces To Watch. Debuting acts are universally considered the life blood of the recording industry, and over the last seven years Cash Box has been first to spotlight new and developing artists, many of whom have gone on to chart topping successes. Having chronicled the development of new talent these seven years, it gives us great pleasure to celebrate their success with our seventh annual New Faces To Watch Supplement. We will again honor those artists who have rewarded the faith, energy, committment and vision of their labels this past year. The supplemenfs layout will be in easy reference pull-out form, making it a year-round historical gudie for the industry. It will contain select, original profiles as well as an updated summary including chart histories, gold and platinum achievements, grammy awards, and revised up-to-date biographies. We know you will want to participate in this tribute, showing both where we have been and where we are going as an industry. The New Faces To Watch Supplement will be included in the August 31st issue of Cash Box, on sale August The advertising deadline is August 22nd. Reserve Advertising Space Now! NEW YORK LOS ANGELES NASHVILLE J.B. CARMICLE SPENCE BERLAND JOHN LENTZ 212-586-2640 213-464-8241 615-244-2898 9 C4SH r BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT -

Sprouse, Mario African & African American Studies Department

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 11-6-2015 Sprouse, Mario African & African American Studies Department. Mario Sprouse Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sprouse, Mario. November 6, 2015. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham University. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewee: Mario Sprouse Interviewer: Mark Naison Date of Interview: November 6, 2015 Transcribers: Andrea Benintendi and Morgan Mungerson Mark Naison (MN): Hello! Mario Sprouse (MS): Hello! MN: Today is November 6, 20015 and today we are interviewing Mario Sprouse for the Bronx African American History Project. Mr. Sprouse who grew up on Ritter Place is a great musician, arranger, composer, musical director and we’re very excited to have him here. With us—joining us are Bob Gumbs, community researcher for the Bronx African American History Project and a great music historian himself, Damien Strecker who is the graduate assistant for the project, and Morgan Mungerson who is one of our student assistants and on the camera Andrea Benintendi. So, Mr. Sprouse, could you please spell your name and give us your date of birth. MS: M-A-R-I-O. Middle name Esteban, E-S-T-E-B-A-N. -

1974 Timeline

1974 (Excerpted from Solo in the 70s by Robert Rodriguez © 2014) January Topping the US singles chart: “Time In A Bottle” by Jim Croce “The Joker” by Steve Miller “Show and Tell” by Al Wilson “You’re Sixteen” by Ringo Starr On the airwaves: “One Tin Soldier” by Coven “Sister Mary Elephant” by Cheech and Chong “Smokin’ In The Boys Room” by Brownsville Station Topping the US album chart: The Singles: 1969-1973 by The Carpenters Albums released this month include: Court and Spark by Joni Mitchell Sundown by Gordon Lightfoot Hotcakes by Carly Simon The Way We Were by Barbra Streisand January – Beginning this month and running through till February, Paul and Wings work on Mike McGear’s album at 10CC’s Strawberry Studios Tuesday 8 – The Early Beatles, Capitol’s abridgment of Please Please Me, is finally certified gold nearly eleven years after its issue Monday 28 – “Jet”/“Mamunia” (Apple 1871; peaks at #7) Thursday 31 – Paul and Linda appear on the cover of Rolling Stone Thursday 31 – Film producer Samuel Goldwyn dies at 94 February 1974 Topping the US singles chart: “The Way We Were” by Barbra Streisand “Love’s Theme” by Love Unlimited Orchestra On the airwaves: “Doo Doo Doo Doo Doo (Heartbreaker)” by the Rolling Stones “Americans” by Byron MacGregor “Let Me Be There” by Olivia Newton-John Topping the US album chart: You Don’t Mess Around With Jim by Jim Croce Albums released this month include: Radio City by Big Star Can’t Get Enough by Barry White Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal by Lou Reed What Were Once Vices Are Now Habits by the Doobie Brothers