Lennie Tristano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazzpress 0612

CZERWIEC 2012 Gazeta internetowa poświęcona muzyce improwizowanej ISSN 2084-3143 KONCERTY Medeski, Martin & Wood 48. Jazz nad Odrą i 17. Muzeum Jazz Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia Mojito w Duc de Lombards z Giladem Hekselmanem Śląski Festiwal Jazzowy Marcus Miller Jarosław Śmietana Trio na Mokotów Jazz Fest Bruce Springsteen And The E Street Band Joscho Stephan W maju Szczecin zakwitł jazzem Mazurki Artura Dutkiewicza na żywo KONKURSY Artur Dutkiewicz, fot. Krzysztof Wierzbowski i Bogdan Augustyniak SPIS TREŚCI 3 – Od Redakcji 68 – Publicystyka 4 – KONKURSY 68 Monolog ludzkich rzeczy 6 – Wydarzenia 72 – Wywiady 72 Jarosław Bothur i Arek Skolik: 8 – Płyty Wszystko ma swoje korzenie 8 RadioJAZZ.FM poleca 77 Aga Zaryan: 10 Nowości płytowe Tekst musi być o czymś 14 Recenzje 84 Nasi ludzie z Kopenhagi i Odense: Imagination Quartet Tomek Dąbrowski, Marek Kądziela, – Imagination Quartet Tomasz Licak Poetry – Johannes Mossinger Black Radio – Robert Glasper Experiment 88 – BLUESOWY ZAUŁEK Jazz w Polsce – wolność 88 – Magia juke jointów rozimprowizowana? 90 – Sean Carney w Warszawie 21 – Przewodnik koncertowy 92 – Kanon Jazzu 21 RadioJAZZ.FM i JazzPRESS polecają y Dexter Calling – Dexter Gordon 22 Letnia Jazzowa Europa Our Thing – Joe Henderson 23 Mazurki Artura Dutkiewicza na żywo The Most Important Jazz Album 26 MM&W – niegasnąca muzyczna marka Of 1964/1965 – Chet Baker 28 48. Jazz nad Odrą i 17. Muzeum Jazz Zawsze jest czas pożegnań 40 Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia i rzecz o bansuri 100 – Sesje jazzowe 43 Mojito w Duc de Lombards 108 – Co w RadioJAZZ.FM -

Student Ensemble: Jazz Combos School of Music Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 4-4-2013 Student Ensemble: Jazz Combos School of Music Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation School of Music, "Student Ensemble: Jazz Combos" (2013). School of Music Programs. 467. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/467 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State University Illinois State University College of Fine Arts College of Fine Arts School of Music School of Music __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Illinois State University Illinois State University Jazz Combos Jazz Combos ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Kemp Recital Hall Kemp Recital Hall April 4, 2013 April 4, 2013 Thursday Evening Thursday Evening 8:00 p.m. 8:00 p.m. This is the one hundred and thirty-ninth program of the 2012-2013 season. This is the one hundred and thirty-ninth program of the 2012-2013 season. Program Program Please turn off cell phones and pagers for the duration of the concert. Thank you. Please turn off cell phones and pagers for the duration of the concert. Thank -

Liebman Expansions

MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE LIEBMAN EXPANSIONS CHICO NIK HOD LARS FREEMAN BÄRTSCH O’BRIEN GULLIN Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Chico Freeman 6 by terrell holmes [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Nik Bärtsch 7 by andrey henkin General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Dave Liebman 8 by ken dryden Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Hod O’Brien by thomas conrad Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Lars Gullin 10 by clifford allen [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Rudi Records by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above CD Reviews or email [email protected] 14 Staff Writers Miscellany David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, 37 Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Event Calendar 38 Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Tracing the history of jazz is putting pins in a map of the world. -

Anticommercialism in the Music and Teachings of Lennie Tristano

ANTICOMMERCIALISM IN THE MUSIC AND TEACHINGS OF LENNIE TRISTANO James Aldridge Department of Music Research, Musicology McGill University, Montreal July 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS © James Aldridge 2016 i CONTENTS ABSTRACT . ii RÉSUMÉ . iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . v PREFACE . vi INTRODUCTION . 1 LITERATURE REVIEW . 8 CHAPTER 1 Redefining Jam Session Etiquette: A Critical Look at Tristano’s 317 East 32nd Street Loft Sessions . 19 CHAPTER 2 The “Cool” and Critical Voice of Lennie Tristano . 44 CHAPTER 3 Anticommercialism in the Pedagogy of Lennie Tristano . 66 CONCLUSION . 86 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 91 ii Abstract This thesis examines the anticommercial ideology of Leonard Joseph (Lennie) Tristano (1919 – 1978) in an attempt to shed light on underexplored and misunderstood aspects of his musical career. Today, Tristano is known primarily for his contribution to jazz and jazz piano in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He is also recognized for his pedagogical success as one of jazz’s first formal teachers. Beyond that, however, Tristano remains a peripheral figure in much of jazz’s history. In this thesis, I argue that Tristano’s contributions are often overlooked because he approached jazz creation in a way that ignored unspoken commercially-oriented social expectations within the community. I also identify anticommercialism as the underlying theme that influenced the majority of his decisions ultimately contributing to his canonic marginalization. Each chapter looks at a prominent aspect of his career in an attempt to understand how anticommercialism affected his musical output. I begin by looking at Tristano’s early 1950s loft sessions and show how changes he made to standard jam session protocol during that time reflect the pursuit of artistic purity—an objective that forms the basis of his ideology. -

Warne Marsh Quintet Jazz of Two Cities Mp3, Flac, Wma

Warne Marsh Quintet Jazz Of Two Cities mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Jazz Of Two Cities Country: Spain Released: 2003 Style: Cool Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1461 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1907 mb WMA version RAR size: 1842 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 178 Other Formats: VOX MMF DXD VOC AU AIFF AAC Tracklist Hide Credits Smog Eyes 1-1 3:35 Composed By – Ted Brown Ear Conditioning 1-2 5:14 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Lover Man 1-3 4:28 Composed By – Ram Ramirez* Quintessence 1-4 4:15 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Jazz Of Two Cities 1-5 4:33 Composed By – Ted Brown Dixie's Dilemma 1-6 4:21 Composed By – Warne Marsh These Are The Things I Love (Based On Tchaikovsky's Opus 42, 3rd Movement) 1-7 3:59 Adapted By – Warne Marsh I Never Knew 1-8 5:02 Composed By – Gus Kahn, Ted Fiorito Ben Blew 1-9 3:37 Composed By – Ben Tucker Time's Up 1-10 3:08 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Earful 1-11 4:35 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Black Jack 1-12 3:15 Composed By – Warne Marsh Jazz Of Two Cities (Alternate Take) 1-13 4:39 Composed By – Ted Brown I Never Knew (Alternate Take) 1-14 5:09 Composed By – Gus Kahn, Ted Fiorito Aretha 2-1 4:59 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Long Gone 2-2 4:47 Composed By – Warne Marsh Once We Were Young 2-3 3:46 Composed By – Walter Gross Foolin' Myself 2-4 4:31 Composed By – Andy Razaf, Fats Waller Avalon 2-5 3:04 Composed By – Jolson*, DeSylva*, Rose* On A Slow Boat To China 2-6 5:17 Composed By – Frank Loesser Crazy She Calls Me 2-7 4:15 Composed By – Al Cahn Broadway 2-8 5:58 Composed By – Haydn Wood, Teddy McRae Arrival 2-9 3:48 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Au Privave 2-10 1:08 Composed By – Charlie Parker Ad Libido 2-11 2:43 Composed By – Ronnie Ball 2-12 Bobby Troup Discusses Warne's Music.. -

JREV3.6FULL.Pdf

KNO ED YOUNG FM98 MONDAY thru FRIDAY 11 am to 3 pm: CHARLES M. WEISENBERG SLEEPY I STEVENSON SUNDAY 8 to 9 pm: EVERYDAY 12 midnite to 2 am: STEIN MONDAY thru SATURDAY 7 to 11 pm: KNOBVT THE CENTER OF 'He THt fM DIAL FM 98 KNOB Los Angeles F as a composite contribution of Dom Cerulli, Jack Tynan and others. What LETTERS actually happened was that Jack Tracy, then editor of Down Beat, decided the magazine needed some humor and cre• ated Out of My Head by George Crater, which he wrote himself. After several issues, he welcomed contributions from the staff, and Don Gold and I began. to contribute regularly. After Jack left, I inherited Crater's column and wrote it, with occasional contributions from Don and Jack Tynan, until I found that the well was running dry. Don and I wrote it some more and then Crater sort of passed from the scene, much like last year's favorite soloist. One other thing: I think Bill Crow will be delighted to learn that the picture of Billie Holiday he so admired on the cover of the Decca Billie Holiday memo• rial album was taken by Tony Scott. Dom Cerulli New York City PRAISE FAMOUS MEN Orville K. "Bud" Jacobson died in West Palm Beach, Florida on April 12, 1960 of a heart attack. He had been there for his heart since 1956. It was Bud who gave Frank Teschemacher his first clarinet lessons, weaning him away from violin. He was directly responsible for the Okeh recording date of Louis' Hot 5. -

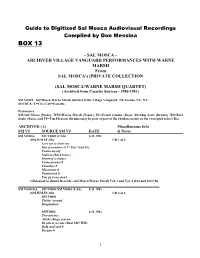

SAL MOSCA/WARNE MARSH QUARTET) (Archived from Cassette Sources - 1980-1981)

Guide to Digitized Sal Mosca Audiovisual Recordings Compiled by Don Messina BOX 13 - SAL MOSCA - ARCHIVED VILLAGE VANGUARD PERFORMANCES WITH WARNE MARSH From SAL MOSCA's |PRIVATE COLLECTION (SAL MOSCA/WARNE MARSH QUARTET) (Archived from Cassette Sources - 1980-1981) SM V000X– Sal Mosca-Warne Marsh Quartet at the Village Vanguard, 7th Avenue, NY, NY; SOURCE: C=CD; CAS=Cassette. Performers: SM=Sal Mosca (Piano); WM=Warne Marsh (Tenor); FC=Frank Canino (Bass); SS=Skip Scott (Drums). (ES=Earl Sauls (Bass), and TP=Tim Pleasant (Drums) may be part of part of the rhythm section on the excerpted solos CDs). ARCHIVED (A) Miscellaneous Info SM V# SOURCE SM V# DATE & Notes SM V0001a SM V0001 (CAS) 8.11.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 1 of 2 Love me or leave me Out of nowhere (317 East 32nd St.) Foolin myself Indiana (Back home) Ghost of a chance Crosscurrents # Cherokee # Marionette # Featherbed # You go to my head # Released on Zinnia Records - Sal Mosca/Warne Marsh Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (103 and 104 CD) ________________________________________________________________________ SM V0001b-2 SM V0001/SM V0002 (CAS) 8.11.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 2 of 2 SM V0001 Fishin' around Imagination SMV0002 8.11.1981 Two not one All the things you are Its you or no one (Duet SM+WM) Body and soul # Dreams # 1 Pennies in minor Sophisticated lady (incomplete) # Released on Zinnia Records - Sal Mosca/Warne Marsh Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (103 and 104CD) ________________________________________________________________________ SM V0003a SM V0003 (CAS) 8.12.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 1 of 2 Its you or no one 317 East 32nd St. -

Stomp 39 He Joint Was Packed, the Dance Floor Twas Jumping, and the Music Was HOT

Volume 36 • Issue 4 April 2008 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Stomp 39 he joint was packed, the dance floor Twas jumping, and the music was HOT. In a nutshell, the NJJS’s annual Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp delivered the goods for the 39th straight year. The fun began at noon with a set of modern The musician of the year award jazz classics, smoothly performed by a septet was presented to Eddie Bert. of Jersey college players, and was capped five The octogenarian trom- hours later by some rocking versions of bonist drove down from Swing Era standards by George Gee’s Jump, his home in Jivin’ Wailers Swing Orchestra, who closed Connecticut to pick the show to rousing applause. In between, up his award, but had the clock was turned back to the 1920s and to leave early to get ’30s as vocalist Barbara Rosene and group, back for a gig later in the Jon Erik-Kellso Group and the Smith the day! Street Society Band served up a tasty banquet And John Becker, who had been of vintage Jazz Age music. The Hot Jazz fans unable to attend the NJJS Annual in the audience ate it all up. Meeting in December, was on hand to There were some special guests in attendance receive the 2007 Nick Bishop Award. at the Birchwood Manor in Whippany on The event also featured the presenta- March 2. NJJS President Emeritus, and tion of annual NJJS Pee Wee Russell Stomp founder, Jack Stine, took the stage to scholarship awards to five New present Rutgers University Institute of Jazz Jersey jazz studies college students. -

A Lennie Tristano Retrospective Once, As He Does with His International-Flavored Group Spinning Repetition with Pointillism

the history of jazz piano is also a history of the merger playing as three-in-one. Rodgers-Hart’s “My Romance” of jazz and specifically ‘classical’ elements, whether it is perfect in this setting as Capdevila and his cohorts is Tatum’s adventures in the repertoire (Chopin, find mystery and magic going from inward to Dvořák, Massenet), Powell’s variations (“Bud on expansive. Klampanis solos with a great sense of the Bach”) or Bill Evans’ importation of Eastern European melody and its possibilities. modernist harmony. Stabinsky continues what has Enchanting moments appear throughout—in the become a long line: he has touch, technique and syncopated rhythms of “Another Day”; beautifully harmonic breadth contributing to a genuinely personal relaxed swing of “Workshop”, which features electric synthesis, contrasting polyrhythmic and polytonal piano and some fine brush work; and very danceable Monk Restrung complexities with intense single-note lines, spare, “Cabana Leo”, which, like much of this wonderful Freddie Bryant (s/r) moody harmonies and occasional punchy trebles. recording, celebrates both old and new worlds. by Joel Roberts Each piece is a probe into both the impulses of the moment and an extended investigation. The opening For more information, visit lluiscapdevila.com. This project Freddie Bryant has made a name for himself over the “...After It’s Over” floats between Scriabin and blues, is at Cleopatra’s Needle Nov. 18th. See Calendar. past two decades as a highly skilled and versatile individual phrases alternating consonant sunlight and guitarist who can play equally well in a variety of jazz dissonant knots at once emotional and harmonic; and non-jazz contexts: classical, AfroCaribbean, world the brief “31” and “For Reel” are very different music, you name it, often combining several genres at explosions, the former bright, the latter contrasting A Lennie Tristano Retrospective once, as he does with his international-flavored group spinning repetition with pointillism. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

MUNI 20071115 – All the Things You Are (Vocal, Piano) 1 Barbra

MUNI 20071115 – All the Things You Are (vocal, piano) 1 Barbra Streisand -voc; studio orchestra conducted by David Shire; Ray Ellis-arr. 1967. CD: Columbia COL 437698 2. 2 Joe Williams -voc; Thad Jones-tp, arr; Eddie „Lockjaw“ Davis, Benny Golson-ts; John Collins-g; Jerry Peters-kb; Norman Simmons-p; John Heard-b; Gerryck King-dr. Ocean Way Studio A, Los Angeles, June 29-30, 1985. CD: Delos 4004. 3 Margaret Whiting -voc; Russell Garcia Orchestra. Los Angeles, January & February 1960. CD: Verve 559 553/2. 4 Ella Fitzgerald -voc; Nelson Riddle Orchestra. Los Angeles, January 1963. CD: Verve V6-4060 / 0075021034754. 5 Rosemary Clooney -voc; Warren Vache-co; Scott Hamilton-ts; John Oddo-p, arr; John Clayton-b; Jeff Hamilton-dr. Coast Recorders, San Francisco, August & November 1988. CD: Recall SMDCD 252. 6 Carmen McRae -voc; Dick Shreve-p; Larry Bunker-vib; Joe Pass-g; Ray Brown-b; Frank Severino-dr. Los Angeles, late 1972. CD: LRC CDC 7970. 7 Betty Carter -voc; Norman Simmons-p; Lisle Atkinson-b; Al Harewood-dr. Village Vanguard, New York, May 22, 1970. CD: Verve 519 851-2. 8 Singers Unlimited : Bonnie Herman, Don Shelton, Gene Puerling, Len Dresslar-voc; Gene Puerling-arr. Villingen, Germany, June 1979. CD: MPS 539 137-2. 9 Eddie Heywood -p; Frank Carroll-b; Terry Snyder-dr. New York City, August 30, 1950. CD: Mosaic MD7-199. 10 Duke Ellington -p; Jimmy Woode-b; Sam Woodyard-dr. Columbia 30th Street Studio, NYC, October 10, 1957. CD: Columbia/Legacy 512920 2. 11 Bill Evans -piano solo. New York City, January 20, 1963. -

'!2G00BJ-Hbfhdj! to a Superb Black Disc and a Cover with Lines Notes by the Famous Barry Ulanov

Atlantic 1217 Lee Konitz With Warne Marsh personnel Lee Konitz (as); Warne Marsh (ts); Ronnie Ball, Sal Mosca (p); Billy Bauer (g); Oscar Pettiford (b); Kenny Clarke (dr) tracks Topsy; There Will Never Be Another You; I Can’t Get Started; Donna Lee; Two Not One; Don’t Squawk; Ronnie’s Line; Background Music What a great rhythm group! A dream comes true: Oscar Pettiford and Kenny Clarke – and then Billy Bauer on the guitar and alternately Ronnie Ball (UK) or Sal Mosca (USA) on the piano. No wonder that things really take off when these masters of improvisation from the Lennie Tristano school get going. catalogue # In June 1955, in the Atlantic studio, standards provided the starting base for the long and 1217 wonderfully sophisticated improvisations by Lee Konitz and Wayne Marsh, who were at that set contents time pupils of the great Chicago maestro. Although the numbers are declared as own com- 1 LP / standard sleeve positions, such as Background Music and Ronnie’s Line, they are actually none other than pricecode adaptations of All Of Me or That Old Feeling – but at the very highest level. Lee Konitz always SC01 called this “The Twelfth Step”. The repertoire is enriched by seldom-heard compositions by the great Oscar Pettiford. “Time-keeping” – a neologism of prime importance for jazz musi- release date November 2018 cians – is the most important element in Donna Lee and There Will Never Be Another You – and there is no better drummer for this music than Kenny “Klook” Clarke, who lived in those days barcode in the USA before moving to Paris in 1956 where there was no racial discrimination.