Jeff Pifher-Wow by Lennie Tristano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Ensemble: Jazz Combos School of Music Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 4-4-2013 Student Ensemble: Jazz Combos School of Music Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation School of Music, "Student Ensemble: Jazz Combos" (2013). School of Music Programs. 467. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/467 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State University Illinois State University College of Fine Arts College of Fine Arts School of Music School of Music __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Illinois State University Illinois State University Jazz Combos Jazz Combos ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Kemp Recital Hall Kemp Recital Hall April 4, 2013 April 4, 2013 Thursday Evening Thursday Evening 8:00 p.m. 8:00 p.m. This is the one hundred and thirty-ninth program of the 2012-2013 season. This is the one hundred and thirty-ninth program of the 2012-2013 season. Program Program Please turn off cell phones and pagers for the duration of the concert. Thank you. Please turn off cell phones and pagers for the duration of the concert. Thank -

Anticommercialism in the Music and Teachings of Lennie Tristano

ANTICOMMERCIALISM IN THE MUSIC AND TEACHINGS OF LENNIE TRISTANO James Aldridge Department of Music Research, Musicology McGill University, Montreal July 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS © James Aldridge 2016 i CONTENTS ABSTRACT . ii RÉSUMÉ . iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . v PREFACE . vi INTRODUCTION . 1 LITERATURE REVIEW . 8 CHAPTER 1 Redefining Jam Session Etiquette: A Critical Look at Tristano’s 317 East 32nd Street Loft Sessions . 19 CHAPTER 2 The “Cool” and Critical Voice of Lennie Tristano . 44 CHAPTER 3 Anticommercialism in the Pedagogy of Lennie Tristano . 66 CONCLUSION . 86 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 91 ii Abstract This thesis examines the anticommercial ideology of Leonard Joseph (Lennie) Tristano (1919 – 1978) in an attempt to shed light on underexplored and misunderstood aspects of his musical career. Today, Tristano is known primarily for his contribution to jazz and jazz piano in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He is also recognized for his pedagogical success as one of jazz’s first formal teachers. Beyond that, however, Tristano remains a peripheral figure in much of jazz’s history. In this thesis, I argue that Tristano’s contributions are often overlooked because he approached jazz creation in a way that ignored unspoken commercially-oriented social expectations within the community. I also identify anticommercialism as the underlying theme that influenced the majority of his decisions ultimately contributing to his canonic marginalization. Each chapter looks at a prominent aspect of his career in an attempt to understand how anticommercialism affected his musical output. I begin by looking at Tristano’s early 1950s loft sessions and show how changes he made to standard jam session protocol during that time reflect the pursuit of artistic purity—an objective that forms the basis of his ideology. -

JREV3.6FULL.Pdf

KNO ED YOUNG FM98 MONDAY thru FRIDAY 11 am to 3 pm: CHARLES M. WEISENBERG SLEEPY I STEVENSON SUNDAY 8 to 9 pm: EVERYDAY 12 midnite to 2 am: STEIN MONDAY thru SATURDAY 7 to 11 pm: KNOBVT THE CENTER OF 'He THt fM DIAL FM 98 KNOB Los Angeles F as a composite contribution of Dom Cerulli, Jack Tynan and others. What LETTERS actually happened was that Jack Tracy, then editor of Down Beat, decided the magazine needed some humor and cre• ated Out of My Head by George Crater, which he wrote himself. After several issues, he welcomed contributions from the staff, and Don Gold and I began. to contribute regularly. After Jack left, I inherited Crater's column and wrote it, with occasional contributions from Don and Jack Tynan, until I found that the well was running dry. Don and I wrote it some more and then Crater sort of passed from the scene, much like last year's favorite soloist. One other thing: I think Bill Crow will be delighted to learn that the picture of Billie Holiday he so admired on the cover of the Decca Billie Holiday memo• rial album was taken by Tony Scott. Dom Cerulli New York City PRAISE FAMOUS MEN Orville K. "Bud" Jacobson died in West Palm Beach, Florida on April 12, 1960 of a heart attack. He had been there for his heart since 1956. It was Bud who gave Frank Teschemacher his first clarinet lessons, weaning him away from violin. He was directly responsible for the Okeh recording date of Louis' Hot 5. -

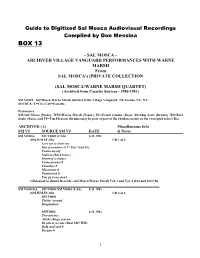

SAL MOSCA/WARNE MARSH QUARTET) (Archived from Cassette Sources - 1980-1981)

Guide to Digitized Sal Mosca Audiovisual Recordings Compiled by Don Messina BOX 13 - SAL MOSCA - ARCHIVED VILLAGE VANGUARD PERFORMANCES WITH WARNE MARSH From SAL MOSCA's |PRIVATE COLLECTION (SAL MOSCA/WARNE MARSH QUARTET) (Archived from Cassette Sources - 1980-1981) SM V000X– Sal Mosca-Warne Marsh Quartet at the Village Vanguard, 7th Avenue, NY, NY; SOURCE: C=CD; CAS=Cassette. Performers: SM=Sal Mosca (Piano); WM=Warne Marsh (Tenor); FC=Frank Canino (Bass); SS=Skip Scott (Drums). (ES=Earl Sauls (Bass), and TP=Tim Pleasant (Drums) may be part of part of the rhythm section on the excerpted solos CDs). ARCHIVED (A) Miscellaneous Info SM V# SOURCE SM V# DATE & Notes SM V0001a SM V0001 (CAS) 8.11.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 1 of 2 Love me or leave me Out of nowhere (317 East 32nd St.) Foolin myself Indiana (Back home) Ghost of a chance Crosscurrents # Cherokee # Marionette # Featherbed # You go to my head # Released on Zinnia Records - Sal Mosca/Warne Marsh Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (103 and 104 CD) ________________________________________________________________________ SM V0001b-2 SM V0001/SM V0002 (CAS) 8.11.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 2 of 2 SM V0001 Fishin' around Imagination SMV0002 8.11.1981 Two not one All the things you are Its you or no one (Duet SM+WM) Body and soul # Dreams # 1 Pennies in minor Sophisticated lady (incomplete) # Released on Zinnia Records - Sal Mosca/Warne Marsh Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (103 and 104CD) ________________________________________________________________________ SM V0003a SM V0003 (CAS) 8.12.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 1 of 2 Its you or no one 317 East 32nd St. -

A Lennie Tristano Retrospective Once, As He Does with His International-Flavored Group Spinning Repetition with Pointillism

the history of jazz piano is also a history of the merger playing as three-in-one. Rodgers-Hart’s “My Romance” of jazz and specifically ‘classical’ elements, whether it is perfect in this setting as Capdevila and his cohorts is Tatum’s adventures in the repertoire (Chopin, find mystery and magic going from inward to Dvořák, Massenet), Powell’s variations (“Bud on expansive. Klampanis solos with a great sense of the Bach”) or Bill Evans’ importation of Eastern European melody and its possibilities. modernist harmony. Stabinsky continues what has Enchanting moments appear throughout—in the become a long line: he has touch, technique and syncopated rhythms of “Another Day”; beautifully harmonic breadth contributing to a genuinely personal relaxed swing of “Workshop”, which features electric synthesis, contrasting polyrhythmic and polytonal piano and some fine brush work; and very danceable Monk Restrung complexities with intense single-note lines, spare, “Cabana Leo”, which, like much of this wonderful Freddie Bryant (s/r) moody harmonies and occasional punchy trebles. recording, celebrates both old and new worlds. by Joel Roberts Each piece is a probe into both the impulses of the moment and an extended investigation. The opening For more information, visit lluiscapdevila.com. This project Freddie Bryant has made a name for himself over the “...After It’s Over” floats between Scriabin and blues, is at Cleopatra’s Needle Nov. 18th. See Calendar. past two decades as a highly skilled and versatile individual phrases alternating consonant sunlight and guitarist who can play equally well in a variety of jazz dissonant knots at once emotional and harmonic; and non-jazz contexts: classical, AfroCaribbean, world the brief “31” and “For Reel” are very different music, you name it, often combining several genres at explosions, the former bright, the latter contrasting A Lennie Tristano Retrospective once, as he does with his international-flavored group spinning repetition with pointillism. -

MILES DAVIS: the ROAD to MODAL JAZZ Leonardo Camacho Bernal

MILES DAVIS: THE ROAD TO MODAL JAZZ Leonardo Camacho Bernal Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: John Murphy, Major Professor Cristina Sánchez-Conejero, Minor Professor Mark McKnight, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Camacho Bernal, Leonardo, Miles Davis: The Road to Modal Jazz. Master of Arts (Music), May 2007, 86 pp., 19 musical examples, references, 124 titles. The fact that Davis changed his mind radically several times throughout his life appeals to the curiosity. This thesis considers what could be one of the most important and definitive changes: the change from hard bop to modal jazz. This shift, although gradual, is best represented by and culminates in Kind of Blue, the first Davis album based on modal style, marking a clear break from hard bop. This thesis explores the motivations and reasons behind the change, and attempt to explain why it came about. The purpose of the study is to discover the reasons for the change itself as well as the reasons for the direction of the change: Why change and why modal music? Copyright 2006 by Leonardo Camacho Bernal ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES............................................................................................... v Chapters 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... -

The Cultural Challenges and Limitations of Free Jazz in the 1960S

Iain Anderson. This Is Our Music: Free Jazz, the Sixties, and American Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006. vi + 258 pp. $22.00, paper, ISBN 978-0-8122-2003-2. Reviewed by Zachary J. Lechner Published on H-1960s (July, 2008) The emergence of free jazz music in the 1960s ing status of jazz" (p. 2). He posits two chief ques‐ presented a significant challenge to the jazz tions: How influential were black activists and in‐ canon. Free improvisers such as Ornette Coleman, tellectuals in transforming the cultural hierarchy, Cecil Taylor, Eric Dolphy, Archie Shepp, and Sun and, after World War II, did a broadening of Ra pushed the boundaries of jazz. For these per‐ wealth and education bridge the void between formers, bebop, hard bop, modal, and other jazz high and low culture? Anderson argues that free innovations of the 1940s and 1950s were too re‐ improvisers and their supporters challenged the strictive. They abandoned fxed chord changes promotion of jazz as "America's artform" and of‐ and tempos. For some listeners, it sounded inno‐ ten attempted to claim it as distinctive of the vative and exciting; others found the music chaot‐ African American experience. In doing so, they ic and threatening. drove away most of the jazz audience. Universi‐ Iain Anderson, an associate professor of histo‐ ties and other high arts institutions interested in ry at Dana College, disagrees with the critics of better representing and supporting black culture, free improvisation, as Anderson generally refers as well as the avant-garde in the arts, welcomed to the style. -

Brief Biography of Lee Konitz

Lee Konitz: Conversations on the Improviser's Art Andy Hamilton http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=130264 The University of Michigan Press, 2007 Brief Biography of Lee Konitz Lee Konitz is one of the most original and distinctive alto saxophonists in the history of jazz. With Sonny Rollins, Max Roach, and a few others, he is one of the surviving master improvisers of the bebop generation. But his apprenticeship to bebop was indirect, and he has carved out an uncompro- mising solo career guided by a singular artistic vision. He seeks out chal- lenging situations and strives for perfection in the momentary art of impro- visation. He is unerringly self-critical and always stretches himself to do the best work possible. Though Konitz is a highly re›ective musician, what he plays is intuitive, the product of an intensely emotional sensibility. It’s strik- ing how ingenious Konitz has been in creating novel contexts for the tradi- tional approach of “theme and variations” that he follows. In albums such as Peacemeal or Duets from the 1960s, the solo album Lone-Lee from the 1970s, right up to the recent duo album with drummer Matt Wilson, Gong With Wind, the saxophonist has been concerned to develop new formats for improvisation. Konitz was born on October 13, 1927, in Chicago, of Austrian/Russian Jewish parents. At the age of eleven he picked up his ‹rst instrument, the clarinet, on which he received classical lessons before switching to tenor and then alto saxophone. In 1943 he met the decisive personal and musical in›uence of his life, the blind teacher and pianist Lennie Tristano. -

Listing of Albums to Be Donated to the Edmonds School District (April 2011)

EXHIBIT A Listing of Albums to be Donated to the Edmonds School District (April 2011) A. Time Life Records “Concerts of Great Music” • An Index to the Recordings – a 64 page hard-cover book • The Rich World of Music by Henry Anatole Grunwald, an Introduction to the Story of Great Music STL 140 – The Romantic Era STL 141 – Age of Elegance STL 142 – The Opulent Era STL 143 – Age of Revolution STL 144 – The Baroque Era STL 145 – The Music of Today STL 146 – The Early Twentieth Century STL 147 – Prelude to Modern Music STL 148 – Slavic Traditions STL 149 – The Spanish Style STL 150 – From the Renaissance STL 151 – The Baroque Era (a follow-on album) STL 152 – The Romantic Era (a follow-on album) STL 153 – Age of Elegance (a follow-on album) STL 154 – Age of Revolution (a follow-on album) STL 155 – Prelude to Modern Music (a follow-on album) STL 156 – The Early Twentieth Century (a follow-on album) STL 157 – Slavic Traditions (a follow-on album) STL 158 – The Opulent Era (a follow-on album) STL 159 – The Music of Today (a follow-on album) STL 160 – From the Renaissance (a follow-on album) STL 161 – The Spanish Style (a follow-on album) Page 1 of 4) B. The Franklin Mint Record Society’s “The Greatest Recordings of the Big Band Era” • The Greatest Recordings of the Big Band Era , an introductory promotional pamphlet • The Greatest Recordings of the Big Band Era , Cross Reference Index (Issues 1-50) Record # Bands Featured 1/2 Glenn Miller/Will Bradley/Orrin Tucker/Don Redman 3/4 Harry James/Horace Heidt/Jack Jenney/Claude Hopkins 5/6 Vaughan -

9780472115877-Fm.Pdf

Lee Konitz Lee Konitz Conversations on the Improviser’s Art Andy Hamilton THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2007 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2010 2009 2008 2007 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hamilton, Andy, 1957– Lee Konitz : conversations on the improviser’s art / Andy Hamilton. p. cm. — (Jazz perspectives) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-472-11587-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-11587-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-472-03217-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-03217-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Konitz, Lee— Interviews. 2. Saxophonists—United States—Interviews. 3. Jazz musicians—United States—Interviews. 4. Musicians—Interviews. 5. Jazz—History and criticism. I. Konitz, Lee. II. Title. ML419.K66H36 2007 788.7'3165092—dc22 [B] 2006032064 [Frontispiece] “Listen” picture, London, 1987 (Courtesy of Caroline Forbes.) To the memory of Lennie Tristano (1919–1978) That’s my way of preparation—to not be prepared. And that takes a lot of preparation! —Lee Konitz Contents Author’s Introduction xi Foreword by Joe -

An Analysis of the Compositions of Bill Evans, Billy Strayhorn, and Bill Murray

Billy's Touch: An Analysis of the Compositions of Bill Evans, Billy Strayhorn, and Bill Murray J. William Murray Towson University March, 2011 Billy's Touch Introduction Composers of any musical style are influenced by what they hear. There are certain sounds that resonate with each composer and musical elements that create these sounds will appear in his/her works. In addition to being influenced through the listening process, musical elements of others composers are learned by analyzing their works, transcribing compositions or other means of study and will also likely find their way into compositions. The study of music theory will also influence what appears in whatever they write or arrange. Because of all these influences and many more things that impact a particular composition, it is difficult to determine a specific influencer for most composers. However, most times when they are asked whose works they admire, they are able to name several composers that are more meaningful. In my case, there are two composers, Bill Evans (1929- 1980) and Billy Strayhorn (1915-1967), whose compositions have a particular resonance with me. Why am I drawn to these composers? Why do I enjoy listening to their works? Why do I enjoy playing their tunes on the piano? These are all questions that I have been unable to answer other than I enjoy listening to them. As part of my interest in and study of jazz, I have begun to compose tunes to be played primarily by small jazz ensembles. If the above hypothesis is true, characteristics of Evans's and Strayhorn's music should appear in my compositions. -

'Cliques Are Destroying Jazz: Lennie Tristano by JOHN S

'Cliques Are Destroying Jazz: Lennie Tristano By JOHN S. WILSON New York—The efforts of such groups as the Shearing quintet and the Bird-with-strings combo to wean the public to bop by offering it in a commercialized form is producing exactly the opposite effect, according to Lennie Triatano. lennir, one of jazz's most adamant* iconoclasts, says such efforts arr killing off the potential jazz audi ence and lousing up the musician* Axel Stordahl To VOL. 17—No. 20 CHICAGO. OCTOBER 6. 1750 involved. (Copyright, I9W, Dowa leaf, lac.)_______________________________________ “If you give watered-down bop to the public,” he says, “they’d Rejoin The Voice rather near that than the real New York—Axel Stordahl, who thing. Has George Shearing helped had been Frank Sinatra’s regular Disc Sales Up jazz by making hi* bop a filling in conductor and arranger until about Korean Troops Get Musk side a sandwich of familiar melo a year ago, will be back with the dy? Obviously not, because there Voice again this season. Stordahl an fewer places where jazz can be will wave the baton on Sinatra’s Over 49 Mark played today than there wen* when video show and will also work with it. Gecxge and his quintet started out. him again on records. For the last New York—Financial statements year Sinatra has used a number of look at Bird asued in the last month indicate different leaders for hi« backing, that record sales are booming along "Look what happened to Charlie with Skitch Henderson handling at a better rate than they did a Parker He made pime records, fea the chore for several months be year ago.