Lennie Tristano's Teaching Method, Followed with a Guitar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ألبوù… (الألبوù…ات & الجØ

Lee Konitz ألبوم قائمة (الألبوم ات & الجدول الزمني) Jazz Nocturne https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/jazz-nocturne-30595290/songs Live at the Half Note https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/live-at-the-half-note-25096883/songs Lee Konitz with Warne Marsh https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lee-konitz-with-warne-marsh-20813610/songs Lee Konitz Meets Jimmy Giuffre https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lee-konitz-meets-jimmy-giuffre-3228897/songs Organic-Lee https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/organic-lee-30642878/songs https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lee-konitz-meets-warne-marsh-again- Lee Konitz Meets Warne Marsh Again 28405627/songs Subconscious-Lee https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/subconscious-lee-7630954/songs https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/an-image%3A-lee-konitz-with-strings- An Image: Lee Konitz with Strings 24966652/songs Lee Konitz Plays with the Gerry https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lee-konitz-plays-with-the-gerry-mulligan- Mulligan Quartet quartet-24078058/songs Anti-Heroes https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/anti-heroes-28452844/songs Alto Summit https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/alto-summit-28126595/songs Pyramid https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/pyramid-28452798/songs Live at Birdland https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/live-at-birdland-19978246/songs Oleo https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/oleo-28452776/songs Very Cool https://ar.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/very-cool-25096889/songs -

Lee Konitz Nonet Yes, Yes, Nonet Mp3, Flac, Wma

Lee Konitz Nonet Yes, Yes, Nonet mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Yes, Yes, Nonet Country: Japan Released: 1979 Style: Post Bop, Contemporary Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1260 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1226 mb WMA version RAR size: 1987 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 665 Other Formats: MP1 DMF TTA RA VOX AHX MP2 Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Death Of A Nation 6:05 A2 Languid 6:11 Footprints A3 7:59 Written-By – W. Shorter* Stardust B1 5:10 Written-By – H. Carmichael* B2 Primrose Path 6:30 B3 Noche Triste 4:32 My Buddy B4 3:30 Written-By – Kahn*, Donaldson* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – SteepleChase Records Copyright (c) – SteepleChase Records Credits Alto Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone – Lee Konitz Baritone Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone – Ronnie Cuber Bass – Buster Williams Design [Cover], Layout – Per Grunnet Drums – Billy Hart Liner Notes – Torbjørn Sjøgren Piano – Harold Danko Producer, Mixed By, Photography By – Nils Winther Recorded By – Elvin Campbell Trombone – Jimmy Knepper Trombone [Bass] – Sam Burtis Trumpet, Flugelhorn – John Eckert, Tom Harrell Written-By – Jimmy Knepper (tracks: A1, A2, B2, B3) Notes JAPAN Press with OBI and insert SAMPLE/PROMO COPY Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Lee Konitz Yes, Yes, Nonet (LP, SCS-1119 SteepleChase SCS-1119 Denmark 1979 Nonet Album) Lee Konitz SCCD-31119 Yes, Yes, Nonet (CD) SteepleChase SCCD-31119 Denmark 1986 Nonet Lee Konitz Yes, Yes, Nonet (CD, SCCD-31119 SteepleChase SCCD-31119 Denmark 1986 Nonet Album) Related Music albums to Yes, Yes, Nonet by Lee Konitz Nonet Mingus - Something Like A Bird Duke Ellington And His Orchestra - 1927-1931 Lee Konitz - Pride Duke Ellington And His Orchestra - 1938-1939 Pierre Dørge & New Jungle Orchestra - Even The Moon Is Dancing Lou Donaldson - The Best Of Lou Donaldson Vol. -

Short Takes Jazz News Festival Reviews Jazz Stories Interviews Columns

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC SHORT TAKES JAZZ NEWS FESTIVAL REVIEWS JAZZAMANCA 2020 JAZZ STORIES PATTY WATERS INTERVIEWS PETER BRÖTZMANN BILL CROW CHAD LEFOWITZ-BROWN COLUMNS NEW ISSUES - REISSUES PAPATAMUS - CD REVIEWS OBITURARIES Volume 46 Number 2 April May June Edition 2020 Ed Schuller (bassist, composer) on GM Recordings My name is Eddy I play the bass A kind of music For the human race And with beauty and grace Let's stay on the case As we look ahead To an uncertain space Peace, Music Love and Life" More info, please visit: www.gmrecordings.com Email: [email protected] GM Recordings, Inc. P.O. Box 894 Wingdale, NY 12594 3 | CADENCE MAGAZINE | APRIL MAY JUNE 2016 L with Wolfgang Köhler In the Land of Irene Kral & Alan Broadbent Live at A-Trane Berlin “The result is so close, so real, so beautiful – we are hooked!” (Barbara) “I came across this unique jazz singer in Berlin. His live record transforms the deeply moving old pieces into the present.” (Album tip in Guido) “As a custodian of tradition, Leuthäuser surprises above all with his flawless intonation – and that even in a live recording!” (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) “Leuthäuser captivates the audience with his adorable, youthful velvet voice.” (JazzThing) distributed by www.monsrecords.de presents Kądziela/Dąbrowski/Kasper Tom Release date: 20th March 2020 For more information please visit our shop: sklep.audiocave.pl or contact us at [email protected] The latest piano trio jazz from Quadrangle Music Jeff Fuller & Friends Round & Round Jeff Fuller, bass • Darren Litzie, piano • Ben Bilello, drums On their 4th CD since 2014, Jeff Fuller & Friends provide engaging original jazz compositions in an intimate trio setting. -

Student Ensemble: Jazz Combos School of Music Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 4-4-2013 Student Ensemble: Jazz Combos School of Music Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation School of Music, "Student Ensemble: Jazz Combos" (2013). School of Music Programs. 467. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/467 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State University Illinois State University College of Fine Arts College of Fine Arts School of Music School of Music __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Illinois State University Illinois State University Jazz Combos Jazz Combos ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Kemp Recital Hall Kemp Recital Hall April 4, 2013 April 4, 2013 Thursday Evening Thursday Evening 8:00 p.m. 8:00 p.m. This is the one hundred and thirty-ninth program of the 2012-2013 season. This is the one hundred and thirty-ninth program of the 2012-2013 season. Program Program Please turn off cell phones and pagers for the duration of the concert. Thank you. Please turn off cell phones and pagers for the duration of the concert. Thank -

The Evolution of Ornette Coleman's Music And

DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY by Nathan A. Frink B.A. Nazareth College of Rochester, 2009 M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Nathan A. Frink It was defended on November 16, 2015 and approved by Lawrence Glasco, PhD, Professor, History Adriana Helbig, PhD, Associate Professor, Music Matthew Rosenblum, PhD, Professor, Music Dissertation Advisor: Eric Moe, PhD, Professor, Music ii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Copyright © by Nathan A. Frink 2016 iii DANCING IN HIS HEAD: THE EVOLUTION OF ORNETTE COLEMAN’S MUSIC AND COMPOSITIONAL PHILOSOPHY Nathan A. Frink, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Ornette Coleman (1930-2015) is frequently referred to as not only a great visionary in jazz music but as also the father of the jazz avant-garde movement. As such, his work has been a topic of discussion for nearly five decades among jazz theorists, musicians, scholars and aficionados. While this music was once controversial and divisive, it eventually found a wealth of supporters within the artistic community and has been incorporated into the jazz narrative and canon. Coleman’s musical practices found their greatest acceptance among the following generations of improvisers who embraced the message of “free jazz” as a natural evolution in style. -

Liebman Expansions

MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE LIEBMAN EXPANSIONS CHICO NIK HOD LARS FREEMAN BÄRTSCH O’BRIEN GULLIN Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2016—ISSUE 169 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : Chico Freeman 6 by terrell holmes [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Nik Bärtsch 7 by andrey henkin General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Dave Liebman 8 by ken dryden Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Hod O’Brien by thomas conrad Editorial: 10 [email protected] Calendar: Lest We Forget : Lars Gullin 10 by clifford allen [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel Spotlight : Rudi Records by ken waxman [email protected] 11 Letters to the Editor: [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above CD Reviews or email [email protected] 14 Staff Writers Miscellany David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, 37 Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Event Calendar 38 Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Tracing the history of jazz is putting pins in a map of the world. -

Anticommercialism in the Music and Teachings of Lennie Tristano

ANTICOMMERCIALISM IN THE MUSIC AND TEACHINGS OF LENNIE TRISTANO James Aldridge Department of Music Research, Musicology McGill University, Montreal July 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS © James Aldridge 2016 i CONTENTS ABSTRACT . ii RÉSUMÉ . iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . v PREFACE . vi INTRODUCTION . 1 LITERATURE REVIEW . 8 CHAPTER 1 Redefining Jam Session Etiquette: A Critical Look at Tristano’s 317 East 32nd Street Loft Sessions . 19 CHAPTER 2 The “Cool” and Critical Voice of Lennie Tristano . 44 CHAPTER 3 Anticommercialism in the Pedagogy of Lennie Tristano . 66 CONCLUSION . 86 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 91 ii Abstract This thesis examines the anticommercial ideology of Leonard Joseph (Lennie) Tristano (1919 – 1978) in an attempt to shed light on underexplored and misunderstood aspects of his musical career. Today, Tristano is known primarily for his contribution to jazz and jazz piano in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He is also recognized for his pedagogical success as one of jazz’s first formal teachers. Beyond that, however, Tristano remains a peripheral figure in much of jazz’s history. In this thesis, I argue that Tristano’s contributions are often overlooked because he approached jazz creation in a way that ignored unspoken commercially-oriented social expectations within the community. I also identify anticommercialism as the underlying theme that influenced the majority of his decisions ultimately contributing to his canonic marginalization. Each chapter looks at a prominent aspect of his career in an attempt to understand how anticommercialism affected his musical output. I begin by looking at Tristano’s early 1950s loft sessions and show how changes he made to standard jam session protocol during that time reflect the pursuit of artistic purity—an objective that forms the basis of his ideology. -

Warne Marsh Quintet Jazz of Two Cities Mp3, Flac, Wma

Warne Marsh Quintet Jazz Of Two Cities mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Jazz Of Two Cities Country: Spain Released: 2003 Style: Cool Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1461 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1907 mb WMA version RAR size: 1842 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 178 Other Formats: VOX MMF DXD VOC AU AIFF AAC Tracklist Hide Credits Smog Eyes 1-1 3:35 Composed By – Ted Brown Ear Conditioning 1-2 5:14 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Lover Man 1-3 4:28 Composed By – Ram Ramirez* Quintessence 1-4 4:15 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Jazz Of Two Cities 1-5 4:33 Composed By – Ted Brown Dixie's Dilemma 1-6 4:21 Composed By – Warne Marsh These Are The Things I Love (Based On Tchaikovsky's Opus 42, 3rd Movement) 1-7 3:59 Adapted By – Warne Marsh I Never Knew 1-8 5:02 Composed By – Gus Kahn, Ted Fiorito Ben Blew 1-9 3:37 Composed By – Ben Tucker Time's Up 1-10 3:08 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Earful 1-11 4:35 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Black Jack 1-12 3:15 Composed By – Warne Marsh Jazz Of Two Cities (Alternate Take) 1-13 4:39 Composed By – Ted Brown I Never Knew (Alternate Take) 1-14 5:09 Composed By – Gus Kahn, Ted Fiorito Aretha 2-1 4:59 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Long Gone 2-2 4:47 Composed By – Warne Marsh Once We Were Young 2-3 3:46 Composed By – Walter Gross Foolin' Myself 2-4 4:31 Composed By – Andy Razaf, Fats Waller Avalon 2-5 3:04 Composed By – Jolson*, DeSylva*, Rose* On A Slow Boat To China 2-6 5:17 Composed By – Frank Loesser Crazy She Calls Me 2-7 4:15 Composed By – Al Cahn Broadway 2-8 5:58 Composed By – Haydn Wood, Teddy McRae Arrival 2-9 3:48 Composed By – Ronnie Ball Au Privave 2-10 1:08 Composed By – Charlie Parker Ad Libido 2-11 2:43 Composed By – Ronnie Ball 2-12 Bobby Troup Discusses Warne's Music.. -

JREV3.6FULL.Pdf

KNO ED YOUNG FM98 MONDAY thru FRIDAY 11 am to 3 pm: CHARLES M. WEISENBERG SLEEPY I STEVENSON SUNDAY 8 to 9 pm: EVERYDAY 12 midnite to 2 am: STEIN MONDAY thru SATURDAY 7 to 11 pm: KNOBVT THE CENTER OF 'He THt fM DIAL FM 98 KNOB Los Angeles F as a composite contribution of Dom Cerulli, Jack Tynan and others. What LETTERS actually happened was that Jack Tracy, then editor of Down Beat, decided the magazine needed some humor and cre• ated Out of My Head by George Crater, which he wrote himself. After several issues, he welcomed contributions from the staff, and Don Gold and I began. to contribute regularly. After Jack left, I inherited Crater's column and wrote it, with occasional contributions from Don and Jack Tynan, until I found that the well was running dry. Don and I wrote it some more and then Crater sort of passed from the scene, much like last year's favorite soloist. One other thing: I think Bill Crow will be delighted to learn that the picture of Billie Holiday he so admired on the cover of the Decca Billie Holiday memo• rial album was taken by Tony Scott. Dom Cerulli New York City PRAISE FAMOUS MEN Orville K. "Bud" Jacobson died in West Palm Beach, Florida on April 12, 1960 of a heart attack. He had been there for his heart since 1956. It was Bud who gave Frank Teschemacher his first clarinet lessons, weaning him away from violin. He was directly responsible for the Okeh recording date of Louis' Hot 5. -

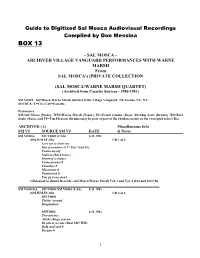

SAL MOSCA/WARNE MARSH QUARTET) (Archived from Cassette Sources - 1980-1981)

Guide to Digitized Sal Mosca Audiovisual Recordings Compiled by Don Messina BOX 13 - SAL MOSCA - ARCHIVED VILLAGE VANGUARD PERFORMANCES WITH WARNE MARSH From SAL MOSCA's |PRIVATE COLLECTION (SAL MOSCA/WARNE MARSH QUARTET) (Archived from Cassette Sources - 1980-1981) SM V000X– Sal Mosca-Warne Marsh Quartet at the Village Vanguard, 7th Avenue, NY, NY; SOURCE: C=CD; CAS=Cassette. Performers: SM=Sal Mosca (Piano); WM=Warne Marsh (Tenor); FC=Frank Canino (Bass); SS=Skip Scott (Drums). (ES=Earl Sauls (Bass), and TP=Tim Pleasant (Drums) may be part of part of the rhythm section on the excerpted solos CDs). ARCHIVED (A) Miscellaneous Info SM V# SOURCE SM V# DATE & Notes SM V0001a SM V0001 (CAS) 8.11.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 1 of 2 Love me or leave me Out of nowhere (317 East 32nd St.) Foolin myself Indiana (Back home) Ghost of a chance Crosscurrents # Cherokee # Marionette # Featherbed # You go to my head # Released on Zinnia Records - Sal Mosca/Warne Marsh Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (103 and 104 CD) ________________________________________________________________________ SM V0001b-2 SM V0001/SM V0002 (CAS) 8.11.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 2 of 2 SM V0001 Fishin' around Imagination SMV0002 8.11.1981 Two not one All the things you are Its you or no one (Duet SM+WM) Body and soul # Dreams # 1 Pennies in minor Sophisticated lady (incomplete) # Released on Zinnia Records - Sal Mosca/Warne Marsh Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (103 and 104CD) ________________________________________________________________________ SM V0003a SM V0003 (CAS) 8.12.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 1 of 2 Its you or no one 317 East 32nd St. -

A Lennie Tristano Retrospective Once, As He Does with His International-Flavored Group Spinning Repetition with Pointillism

the history of jazz piano is also a history of the merger playing as three-in-one. Rodgers-Hart’s “My Romance” of jazz and specifically ‘classical’ elements, whether it is perfect in this setting as Capdevila and his cohorts is Tatum’s adventures in the repertoire (Chopin, find mystery and magic going from inward to Dvořák, Massenet), Powell’s variations (“Bud on expansive. Klampanis solos with a great sense of the Bach”) or Bill Evans’ importation of Eastern European melody and its possibilities. modernist harmony. Stabinsky continues what has Enchanting moments appear throughout—in the become a long line: he has touch, technique and syncopated rhythms of “Another Day”; beautifully harmonic breadth contributing to a genuinely personal relaxed swing of “Workshop”, which features electric synthesis, contrasting polyrhythmic and polytonal piano and some fine brush work; and very danceable Monk Restrung complexities with intense single-note lines, spare, “Cabana Leo”, which, like much of this wonderful Freddie Bryant (s/r) moody harmonies and occasional punchy trebles. recording, celebrates both old and new worlds. by Joel Roberts Each piece is a probe into both the impulses of the moment and an extended investigation. The opening For more information, visit lluiscapdevila.com. This project Freddie Bryant has made a name for himself over the “...After It’s Over” floats between Scriabin and blues, is at Cleopatra’s Needle Nov. 18th. See Calendar. past two decades as a highly skilled and versatile individual phrases alternating consonant sunlight and guitarist who can play equally well in a variety of jazz dissonant knots at once emotional and harmonic; and non-jazz contexts: classical, AfroCaribbean, world the brief “31” and “For Reel” are very different music, you name it, often combining several genres at explosions, the former bright, the latter contrasting A Lennie Tristano Retrospective once, as he does with his international-flavored group spinning repetition with pointillism. -

International Jazz News Festival Reviews Concert

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC INTERNATIONAL JAZZ NEWS TOP 10 ALBUMS - CADENCE CRITIC'S PICKS, 2019 TOP 10 CONCERTS - PHILADEPLHIA, 2019 FESTIVAL REVIEWS CONCERT REVIEWS CHARLIE BALLANTINE JAZZ STORIES ED SCHULLER INTERVIEWS FRED FRITH TED VINING PAUL JACKSON COLUMNS BOOK LOOK NEW ISSUES - REISSUES PAPATAMUS - CD Reviews OBITURARIES Volume 46 Number 1 Jan Feb Mar Edition 2020 CADENCE Mainstream Extensions; Music from a Passionate Time; How’s the Horn Treating You?; Untying the Standard. Cadence CD’s are available through Cadence. JOEL PRESS His robust and burnished tone is as warm as the man....simply, one of the meanest tickets in town. “ — Katie Bull, The New York City Jazz Record, December 10, 2013 PREZERVATION Clockwise from left: Live at Small’s; JP Soprano Sax/Michael Kanan Piano; JP Quartet; Return to the Apple; First Set at Small‘s. Prezervation CD’s: Contact [email protected] WWW.JOELPRESS.COM Harbinger Records scores THREE OF THE TEN BEST in the Cadence Top Ten Critics’ Poll Albums of 2019! Let’s Go In Sissle and Blake Sing Shuffl e Along of 1950 to a Picture Show Shuffl e Along “This material that is nearly “A 32-page liner booklet GRAMMY AWARD WINNER 100 years old is excellent. If you with printed lyrics and have any interest in American wonderful photos are included. musical theater, get these discs Wonderfully done.” and settle down for an afternoon —Cadence of good listening and reading.”—Cadence More great jazz and vocal artists on Harbinger Records... Barbara Carroll, Eric Comstock, Spiros Exaras,