Lacrosse: a History of the Game by Donald M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native American Origins of Modern Lacrosse Jeffrey Carey Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2012 New Directions of Play: Native American Origins of Modern Lacrosse Jeffrey Carey Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carey, Jeffrey, "New Directions of Play: Native American Origins of Modern Lacrosse" (2012). All Theses. 1508. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1508 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW DIRECTIONS OF PLAY: NATIVE AMERICAN ORIGINS OF MODERN LACROSSE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts History by Jeff Carey August 2012 Accepted by: Dr. Paul Anderson, Committee Chair Dr. James Jeffries Dr. Alan Grubb ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to provide a history of lacrosse from the seventeenth century, when the game was played exclusively by Native Americans, to the early decades of the twentieth century, when the game began to flourish in non-Native settings in Canada and the United States. While the game was first developed by Native Americans well before contact with Europeans, lacrosse became standardized by a group of Canadians led by George Beers in 1867, and has continued to develop into the twenty- first century. The thesis aims to illuminate the historical linkages between the ball game that existed among Native Americans at the time of contact with Europeans and the ball game that was eventually adopted and shaped into modern lacrosse by European Americans. -

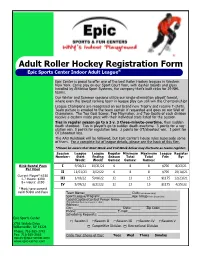

Inline Hockey Registration Form

Adult Roller Hockey Registration Form Epic Sports Center Indoor Adult League® Epic Center is proud to offer one of the best Roller Hockey leagues in Western New York. Come play on our Sport Court floor, with dasher boards and glass installed by Athletica Sport Systems, the company that’s built rinks for 29 NHL teams. Our Winter and Summer sessions utilize our single-elimination playoff format, where even the lowest ranking team in league play can still win the Championship! League Champions are recognized on our brand new Trophy and receive T-shirts. Team picture is emailed to the team captain if requested and goes on our Wall of Champions. The Top Goal Scorer, Top Playmaker, and Top Goalie of each division receive a custom made prize with their individual stats listed for the session. Ties in regular season go to a 3 v. 3 three-minute-overtime, then sudden death shootout. Ties in playoffs go to sudden death overtime. 3 points for a reg- ulation win. 0 points for regulation loss. 2 points for OT/shootout win. 1 point for OT/shootout loss. The AAU Rulebook will be followed, but Epic Center’s house rules supersede some of them. For a complete list of league details, please see the back of this flier. *Please be aware that Start Week and End Week below may fluctuate as teams register. Session League League Regular Minimum Maximum League Register Number: Start Ending Season Total Total Fee: By: Week: Week: Games: Games: Games: Rink Rental Fees I 9/06/21 10/31/21 6 8 8 $700 8/23/21 Per Hour II 11/01/21 1/02/22 6 8 8 $700 10/18/21 Current Player*:$150 -

Redalyc.Using the TGFU Tactical Hierarchy to Enhance Student

Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte ISSN: 1696-5043 [email protected] Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia España Méndez-Giménez, Antonio; Fernández-Río, Javier; Casey, Ashley Using the TGFU tactical hierarchy to enhance student understanding of game play. Expanding the Target Games category Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, vol. 7, núm. 20, mayo-agosto, 2012, pp. 135-141 Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia Murcia, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=163024671008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative calle libre CCD 135 Using the TGFU tactical hierarchy to enhance student understanding of game play. Expanding the Target Games category El uso de la jerarquía táctica de TGFU para mejorar la comprensión del juego de los estudiantes. Ampliando la categoría de juegos de diana Antonio Méndez-Giménez1, Javier Fernández-Río1, Ashley Casey2 1 Universidad de Oviedo (Spain) 2 Universidad de Bedfordshire (UK) CORRESPONDENCIA: Antonio Méndez-Giménez Universidad de Oviedo Facultad de Formación del Profesorado y Educación C/ Aniceto Sela, s/n. Despacho 239 33005 Oviedo (Asturias) 2ECEPCIØNSEPTIEMBREs!CEPTACIØNMAYO [email protected] Abstract Resumen This article reviews the structural and functional Este artículo analiza las características estructurales elements of a group of activities denominated y funcionales de un grupo de actividades denomina- moving target games, and promotes its inclusion in das juegos de diana móvil. También trata de mostrar the Teaching Games for Understanding framework cómo se puede implementar y promover su inclusión en as a new game category. -

Women's Lacrosse Officials Manual

WOMEN’S GAME OFFICIALS TRAINING MANUAL officials development An Official Publication of the National Governing Body of Lacrosse 2020 US LACROSSE WOMEN’S OFFICIALS MANUAL - 2 - 2020 US LACROSSE WOMEN’S OFFICIALS MANUAL CONTENTS PART 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................5 Safety and Responsibility ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Message to Officials .................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 How to Use this Manual ............................................................................................................................................................................................................8 Code of Conduct ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Code of Ethics ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10 PART 2: THE RULES AND PENALTIES ............................................................. -

2 Butts the Lacrosse Scoop Is a Technique Used to Gain Possession of the Ball When It Is on the Ground

Teaching Lacrosse Fundamentals Lacrosse Scoop -2 Butts The lacrosse scoop is a technique used to gain possession of the ball when it is on the ground. The scoop happens as a player moves toward the ball. It is the primary ball recovery technique when a ball is loose and on the ground. In order to perform it the player should drop the head of the stick to the ground and the stick handle should almost but not quite parallel with the ground only a few inches off the ground. The concept is similar to how you would scoop poop (pardon the expression) with a shovel off the concrete. With a quick scoop and then angle upward to keep the ball forced into the deep part of the pocket and from rolling back out. Once in the pocket the player will transition to a cradle, pass, or shot. Recap & Strategies: • Groundball Technique – One hand high on stick, other at butt end – Foot next to ball – Bend knees – 2 butts low – Scoop thru before ball • Groundball Strategies – 1-on-1 –importance of body position - 3 feet before ball can create contact and be physical – 1 –on -2 – consider a flick or kick to a teammate in open space – Scrum – from outside look for ball – get low and burst thru middle getting low as possible – If getting beat to a groundball to drive thru the butt end of the stick – 2–on-1 – man – ball strategy • one person take man, one take ball • Player closest to the ball must attack the ball as if there is no help until communication occurs • Explain the teammate behind is the “QB” telling the person chasing the ball what to do – ie “Take the Man” means turnaround and hinder the opponent so your teammate can get the ball. -

Toronto Has No History!’

‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY By Victoria Jane Freeman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto ©Copyright by Victoria Jane Freeman 2010 ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Victoria Jane Freeman Graduate Department of History University of Toronto The Indigenous past is largely absent from settler representations of the history of the city of Toronto, Canada. Nineteenth and twentieth century historical chroniclers often downplayed the historic presence of the Mississaugas and their Indigenous predecessors by drawing on doctrines of terra nullius , ignoring the significance of the Toronto Purchase, and changing the city’s foundational story from the establishment of York in 1793 to the incorporation of the City of Toronto in 1834. These chroniclers usually assumed that “real Indians” and urban life were inimical. Often their representations implied that local Indigenous peoples had no significant history and thus the region had little or no history before the arrival of Europeans. Alternatively, narratives of ethical settler indigenization positioned the Indigenous past as the uncivilized starting point in a monological European theory of historical development. i i iii In many civic discourses, the city stood in for the nation as a symbol of its future, and national history stood in for the region’s local history. The national replaced ‘the Indigenous’ in an ideological process that peaked between the 1880s and the 1930s. -

Iihf Official Inline Rule Book

IIHF OFFICIAL INLINE RULE BOOK 2015–2018 No part of this publication may be reproduced in the English language or translated and reproduced in any other language or transmitted in any form or by any means electronically or mechanically including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing from the International Ice Hockey Federation. July 2015 © International Ice Hockey Federation IIHF OFFICIAL INLINE RULE BOOK 2015–2018 RULE BOOK 11 RULE 1001 THE INTERNATIONAL ICE HOCKEY FEDERATION (IIHF) AS GOVERNING BODY OF INLINE HOCKEY 12 SECTION 1 – TERMINOLOGY 13 SECTION 2 – COMPETITION STANDARDS 15 RULE 1002 PLAYER ELIGIBILITY / AGE 15 RULE 1003 REFEREES 15 RULE 1004 PROPER AUTHORITIES AND DISCIPLINE 15 SECTION 3 – THE FLOOR / PLAYING AREA 16 RULE 1005 FLOOR / FIT TO PLAY 16 RULE 1006 PLAYERS’ BENCHES 16 RULE 1007 PENALTY BOXES 18 RULE 1008 OBJECTS ON THE FLOOR 18 RULE 1009 STANDARD DIMENSIONS OF FLOOR 18 RULE 1010 BOARDS ENCLOSING PLAYING AREA 18 RULE 1011 PROTECTIVE GLASS 19 RULE 1012 DOORS 20 RULE 1013 FLOOR MARKINGS / ZONES 20 RULE 1014 FLOOR MARKINGS/FACEOFF CIRCLES AND SPOTS 21 RULE 1015 FLOOR MARKINGS/HASH MARKS 22 RULE 1016 FLOOR MARKINGS / CREASES 22 RULE 1017 GOAL NET 23 SECTION 4 – TEAMS AND PLAYERS 24 RULE 1018 TEAM COMPOSITION 24 RULE 1019 FORFEIT GAMES 24 RULE 1020 INELIGIBLE PLAYER IN A GAME 24 RULE 1021 PLAYERS DRESSED 25 RULE 1022 TEAM PERSONNEL 25 RULE 1023 TEAM OFFICIALS AND TECHNOLOGY 26 RULE 1024 PLAYERS ON THE FLOOR DURING GAME ACTION 26 RULE 1025 CAPTAIN -

Forward Falcons | Vii

forward falcons | vii Preface For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, the THE BOWLING GREEN LEGACY majority of women’s athletic contests took BGSU was established in 1910 and opened its place within colleges and universities, rather doors to students in 1914. Most of these students than between them. Perhaps it is for this reason were women, and they began to compete in that documentation of collegiate sport has organized sports almost immediately. Two literary traditionally accorded limited attention to clubs, the Wilsonian Society and the Emerson women’s collegiate sport, giving the impression Society, were established in 1914. Soon after, both that it was nonexistent (Gerber, Felshin, Berlin, societies formed women’s basketball teams, and & Wyrick, 1974). One consequence of this practice highly competitive games between the two were has been the misconception that women’s scheduled during the year. Following these early competitive sport emerged in U.S. colleges and athletic endeavors, hundreds of BGSU women universities only after the passage of Title IX of competed in sports such as archery, softball, the Education Amendments of 1972. We hope to baseball, golf, tennis, field hockey, volleyball, rectify this false impression, particularly with fencing, basketball, soccer, bowling, gymnastics, respect to the women’s sport program at Bowling track and field, lacrosse, swimming and diving, Green State University. and synchronized swimming. These athletes, in concert with the coaches and administrators who led them, established and sustained a strong CAC 1980 women’s athletic presence at BGSU, one on which current athletics opportunities for women are built. These pre-Title IX athletes, coaches, and administrators were, in every sense of the term, “forward Falcons.” Although the early BGSU women’s athletics teams were characterized as “clubs,” by the 1960s most of them clearly had become varsity intercollegiate teams. -

3D BOX LACROSSE RULES

3d BOX LACROSSE RULES 3d BOX RULES INDEX BOX 3d.01 Playing Surface 3d.1 Goals / Nets 3d.2 Goal Creases 3d.3 Division of Floor 3d.4 Face-Off Spots 3d.5 Timer / Scorer Areas GAME TIMING 3d.6 Length of Game 3d.7 Intervals between quarters 3d.8 Game clock operations 3d.9 Officials’ Timeouts THE OFFICIALS 3d.10 Referees 3d.11 Timekeepers 3d.12 Scorers TEAMS 3d.13 Players on Floor 3d.14 Players in Uniform 3d.15 Captain of the Team 3d.16 Coaches EQUIPMENT 3d.17 The Ball 3d.18 Lacrosse Stick 3d.19 Goalie Stick Dimensions 3d.20 Lacrosse Stick Construction 3d.21 Protective Equipment / Pads 3d.22 Equipment Safety 3d.23 Goaltender Equipment PENALTY DEFINITIONS 3d.24 Tech. Penalties / Change of Possession 3d.25 Minor Penalties 3d.26 Major Penalties 3d.27 Misconduct Penalties 3d.28 Game Misconduct Penalty 3d.29 Match Penalty 3d.30 Penalty Shot FLOW OF THE GAME 3d.31 Facing at Center 3d.32 Positioning of all Players at Face-off 3d.33 Facing at other Face-off Spots 3d.34 10-Second count 3d.35 Back-Court Definition 3d.36 30-Second Shot Rule 3d.37 Out of Bounds 3d.38 Ball Caught in Stick or Equipment 3d.39 Ball out of Sight 3d.40 Ball Striking a Referee 3d.41 Goal Scored Definition 3d.42 No Goal 3d.43 Substitution 3d.44 Criteria for Delayed Penalty Stoppage INFRACTIONS 3d.45 Possession / Technical Infractions 3d.46 Offensive Screens / Picks / Blocks 3d.47 Handling the Ball 3d.48 Butt-Ending 3d.49 High-Sticking 3d.50 Illegal Cross-Checking 3d.51 Spearing 3d.52 Throwing the Stick 3d.53 Slashing 3d.54 Goal-Crease Violations 3d.55 Goalkeeper Privileges 3d.56 -

Kolomoki Memoirs

Kolomoki Memoirs By Williams H. Sears Edited with a Preface By Mark Williams and Karl T. Steinen University of Georgia and University of West Georgia University of Georgia Laboratory of Archaeology Series Report Number 70 2013 Preface Mark Williams and Karl T. Steinen This document was written by Bill Sears about 1988 at his home in Vero Beach, Florida. He had retired in 1982 after a career teaching anthropology and archaeology at from Florida Atlantic University. He was working on a book of his professional memoirs, intended to summarize the many archaeological sites he had worked on in Georgia and Florida from 1947 until his retirement. He wrote chapters on his 1948 excavation at the Wilbanks site (9CK5) in the Allatoona Reservoir (Sears 1958), on his 1953 excavation at the famous Etowah site (9BR1), and on his 1947-1951 excavations at the Kolomoki site (9ER1) published in four volumes (Sears 1951a, 1951b, 1953, 1956). These three sites constituted the bulk of his archaeological excavations in Georgia. Apparently he never wrote the intended chapters on his archaeological work in Florida, and the book was never completed. Following his death in December of 1996 (see Ruhl and Steinen 1997), his wife Elsie found the three chapters in a box and passed them on to one of us (Steinen). The chapters on Etowah and Wilbanks are being published separately. The document we present here is his unpublished chapter on the Kolomoki site. It provides a fascinating look at the state of archaeology in Georgia 65 years ago and is filled with pointed insights on many people. -

Haudenosaunee Tradition, Sport, and the Lines of Gender Allan Downey

Document generated on 10/01/2021 2:28 p.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada Engendering Nationality: Haudenosaunee Tradition, Sport, and the Lines of Gender Allan Downey Volume 23, Number 1, 2012 Article abstract The Native game of lacrosse has undergone a considerable amount of change URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1015736ar since it was appropriated from Aboriginal peoples beginning in the 1840s. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1015736ar Through this reformulation, non-Native Canadians attempted to establish a national identity through the sport and barred Aboriginal athletes from See table of contents championship competitions. And yet, lacrosse remained a significant element of Aboriginal culture, spirituality, and the Native originators continued to play the game beyond the non-Native championship classifications. Despite their Publisher(s) absence from championship play the Aboriginal roots of lacrosse were zealously celebrated as a form of North American antiquity by non-Aboriginals The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada and through this persistence Natives developed their own identity as players of the sport. Ousted from international competition for more than a century, this ISSN article examines the formation of the Iroquois Nationals (lacrosse team representing the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in international competition) 0847-4478 (print) between 1983-1990 and their struggle to re-enter international competition as a 1712-6274 (digital) sovereign nation. It will demonstrate how the Iroquois Nationals were a symbolic element of a larger resurgence of Haudenosaunee “traditionalism” Explore this journal and how the team was a catalyst for unmasking intercommunity conflicts between that traditionalism—engrained within the Haudenosaunee’s “traditional” Longhouse religion, culture, and gender constructions— and new Cite this article political adaptations. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide