Halesworth and District Museum : 2011 a Distant Prospect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Awalkthroughblythburghvi

AA WWAALLKK tthhrroouugghh BBLLYYTTHHBBUURRGGHH VVIILLLLAAGGEE Thiis map iis from the bookllet Bllythburgh. A Suffollk Viillllage, on salle iin the church and the viillllage shop. 1 A WALK THROUGH BLYTHBURGH VILLAGE Starting a walk through Blythburgh at the water tower on DUNWICH ROAD south of the village may not seem the obvious place to begin. But it is a reminder, as the 1675 map shows, that this was once the main road to Blythburgh. Before a new turnpike cut through the village in 1785 (it is now the A12) the north-south route was more important. It ran through the Sandlings, the aptly named coastal strip of light soil. If you look eastwards from the water tower there is a fine panoramic view of the Blyth estuary. Where pigs are now raised in enclosed fields there were once extensive tracts of heather and gorse. The Toby’s Walks picnic site on the A12 south of Blythburgh will give you an idea of what such a landscape looked like. You can also get an impression of the strategic location of Blythburgh, on a slight but significant promontory on a river estuary at an important crossing point. Perhaps the ‘burgh’ in the name indicates that the first Saxon settlement was a fortified camp where the parish church now stands. John Ogilby’s Map of 1675 Blythburgh has grown slowly since the 1950s, along the roads and lanes south of the A12. If you compare the aerial view of about 1930 with the present day you can see just how much infilling there has been. -

Blyth Estuary Strategy Preferred Option Consultation September 2005 We Are the Environment Agency

Environment Agency Blyth floodBlyth risk management Blyth Estuary Strategy Preferred option consultation September 2005 We are the Environment Agency. It’s our job to look after your environment and make it a better place - foryou, and for future generations. Your environment is the airyou breathe, the wateryou drink and the ground you walk on. Workingwith business, Government and society as a whole, we are making your environment cleaner and healthier. The Environment Agency. Out there, making your environment a better place. Published by: Environment Agency Kingfisher House Goldhay Way, Orton Goldhay Peterborough PEI 2ZR Tel: 08708 506 506 Fax: 01733 231 840 Email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk © Environment Agency All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. September 2005 Consultation contacts For this project and the whole Suffolk For the Southwold Coastal Frontage Scheme, Estuarine Strategies (SES), please contact: please contact: Nigel Pask, Project Manager Stuart Barbrook Environment Agency Environment Agency Kingfisher House Kingfisher House Goldhay Way Goldhay Way Orton Goldhay Orton Goldhay Peterborough PE2 5ZR Peterborough PE2 5ZR Telephone: 08708 506 506 Telephone: 08708 506 506 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Mike Steen, SES Local Liaison Mr P Patterson Environment Agency Waveney District Council Cobham Road Town Hall Ipswich High Street Suffolk IP3 9JE Lowestoft Suffolk NR32 1HS Telephone: 08708 506 506 E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 01502 562111 E-mail: [email protected] Or Matthew Clegg, Environmental Scientist Black & Veatch Ltd. -

Halesworth Heritage Open Days Saturday 12 - Sunday 13 September 2015

HALESWORTH HERITAGE OPEN DAYS SATURDAY 12 - SUNDAY 13 SEPTEMBER 2015 Halesworth Business Connections Welcome to Halesworth’s FIRST ever Heritage Open Day event Heritage Open Days is England’s biggest Most events do not require booking but for and most popular heritage festival. It those that do the Cut Arts centre is enables people to see and visit thousands providing a free booking service (see back of places that are normally either closed cover). For security’s sake those wishing to to the public or charge for admission. It book need to give contact details, at the happens every year over four days in time of booking. Further information will be September and is a great chance to obtainable on the Open Days themselves at explore local history and culture. 2015 will St Mary’s Parish Church which will be our be the 21st year of Heritage Open Days. Festival Hub. The 20th anniversary year in 2014 broke all records with 3 million visitors visiting All Open day events are FREE. We are very 4,600 properties. grateful to the National Trust which co- ordinates these events and provides support This year Halesworth local volunteers under in kind. Thank you to our local sponsors Durrants, Halesworth Business Connections, an initiative of Halesworth and Blyth Valley Halesworth & Blyth Valley Partnership, Partnership are joining in the festival for two Halesworth Town Council, Musker McIntyre days, Saturday 12th and Sunday 13th and Suffolk County Council whose generous September. Halesworth is a compact market support has made this event possible. town full of charming old buildings. -

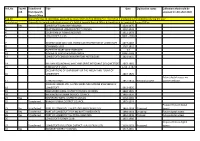

Ref No Top 40 Coll. Transferred from Ipswich Record Office Title Date

Ref_No Top 40 Transferred Title Date Digitisation status Collections that could be coll. from Ipswich accessed in LRO after 2020 Record Office Top 40 One of the top 40 collections accessed by researchers during 2016/17 i.e. more than 5 productions the collection during the year Transferred Originally the whole collection or part of it held at Ipswich Record Office & transferred to Lowestoft Record Office 1 Yes LOWESTOFT BOROUGH RECORDS 1529-1975 3 OULTON BROAD URBAN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1904-1920 4 COLBY FAMILY FISHING RECORDS 1911-1978 5 LOWESTOFT DEEDS 1800 - 2000 7 GEORGE GAGE AND SON, HORSE CAB PROPRIETOR OF LOWESTOFT 1874-1887 8 STANNARD LOGS 1767-1812 9 PAPERS OF MARY ANN STANNARD nd 12 DIARIES OF LADY PLEASANCE SMITH 1804 -1843 13 LOWESTOFT CENSUS ENUMERATORS NOTEBOOKS 1821-1831 14 WILLIAM YOUNGMAN, WINE AND SPIRIT MERCHANT OF LOWESTOFT 1863-1865 15 ARNOLD SHIP LOGS 1729 - 1782 DECLARATIONS OF OWNERSHIP OF THE 'MEUM AND TUUM' OF 16 LOWESTOFT 1867-1925 Future digital access via 17 TITHE RECORDS 1837-1854 National project partner website JOHN CHAMBERS LTD, SHIPBUILDERS AND MARINE ENGINEERS OF 18 LOWESTOFT 1913-1925 19 WANGFORD RURAL DISTRICT COUNCIL RECORDS 1894-1965 20 HALESWORTH URBAN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1855-1970 21 Yes WAINFORD RURAL DISTRICT COUNCIL 1934-1969 22 Transferred BUNGAY URBAN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1875-1974 Proposed future digital 23 Yes Transferred PORT OF LOWESTOFT SHIPS' LOGS AND CREW LISTS 1863-1914 Proposed access 24 Yes Transferred PORT OF LOWESTOFT FISHING BOAT AGREEMENTS 1884-1914 On-going Future digital access 25 Yes Transferred PORT OF LOWESTOFT SHIPPING REGISTERS 1852-1946 Planned Future digital access 26 LOWESTOFT ROTARY CLUB 1962-1980 Proposed future digital 27 Transferred LOWESTOFT VALUATION DISTRICT - VALUATION LISTS 1929-1973 Proposed access 33 Yes WAVENEY DISTRICT COUNCIL 1917-2011 Ref_No Top 40 Transferred Title Date Digitisation status Collections that could be coll. -

The Economic & Social History Of

The Economic & Social History of Halesworth 720 AD - 1902 AD Michael Fordham Halesworth & District Museum charity no.1002545 The Railway Station, Halesworth Suffolk, IP19 8BZ M Fordham 2005 Contents Preface 5 Introduction 5 Map 1: Halesworth: Its location in Northeast Suffolk 6 Map 2: Halesworth 1902. Copy of OS Map. Halesworth and District Museum 7 (i) Geology & Topography of Halesworth 8 (ii) the Archaeology of the Halesworth Area 8 Saxon and Norman Halesworth 720 AD - 1150 AD 9 Map 3.1: Surface/Drift Deposits in the Halesworth Area 10 Map 3.2: The Topography of Halesworth 11 Map 4: Halesworth Archaeology: Fieldwork and Excavations east of the Church 12 (i) The Entries for Halesworth in the Domesday Book (1086) 14 Medieval Halesworth 1200 AD - 1400 AD 14 Map 5: Saxon and Norman Halesworth 720AD - 1150AD: Topography, Geology, observed features and pottery finds 15 Fig 6.1: Barclays Bank Site: Remains of a Saxo-Norman Building 1000AD - 1150AD 16 Fig 6.2: Angel Site: Artistic impression of the Post and Wattle house 1250AD - 1350AD 16 Map 7: Halesworth c1380 18 (i) Butcher-Graziers in Halesworth 1375: 19 (ii) Halesworth Manor: The Demesne (Home Farm) 19 Map 8: The Demesne (Home Farm) of Halesworth Manor 14th C. 21 Fig 9: In the 14th century the named tenements belonging to Halesworth manor included - 22 Halesworth in the Later Medieval Period 1400 AD - 1630 AD 23 Table 10: A Summary of the Halesworth Manorial Accounts, kept by Robert de Bokenham sergeant of the manor Michaelmas 1375 to Michaelmas 1376. 23 Map 11: Halesworth Town: The fixed rents of the late 14thC Tenements and Building Plots 24 Fig 12: The Angel Site Pottery Kiln 1475 - 1525AD 26 (i) The Angel Site Pottery Kiln 27 Fig 13.1: Bell Making and a Pynner’s Workshop 1450 - 1550AD Barclays Bank Site 28 Fig 13.2: Metal Workers furnace c1600AD 29 (ii) Wages & Living Standards in the Halesworth Area 1270 AD - 1579 AD. -

Blyth Estuary Flood Risk Management Strategy: Environmental Report Non Technical Summary

Blyth Estuary Flood Risk Management Strategy: Environmental Report Non Technical Summary Environment Agency Title We are The Environment Agency. It's our job to look after your environment and make it a better place - for you, and for future generations. Your environment is the air you breathe, the water you drink and the ground you walk on. Working with business, Government and society as a whole, we are making your environment cleaner and healthier. The Environment Agency. Out there, making your environment a better place. Published by: Environment Agency Rio House Waterside Drive, Aztec West Almondsbury, Bristol BS32 4UD Tel: 0870 8506506 Email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk © Environment Agency All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Environment Agency Blyth Estuary Flood Risk Management Strategy SEA Environmental Report: Non Technical Summary Non Technical Summary What is this document? will be taken into account in the preparation of the final strategy and a document will be We are the Environment Agency and are produced to explain how any comments have responsible for managing the flood risk arising been considered. from rivers and the sea in England and Wales. There are several areas on the Suffolk Coast Table 1. SEA Structure that are becoming increasingly susceptible to Summary of Environmental Report Structure flooding. Rather than promote individual and Content. projects in isolation we wish to fully consider all related issues and develop long term and Section 1: Introduction sustainable management of flood risk. We describe the role and purpose of SEA in the development of the Blyth Estuary Strategy. -

Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB Pub Walk

14 14 This leaflet has been produced with the generous support of Adnams to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB. In partnership with “Adnams has been proud to work with Suffolk Coast and Local Adnams pub Heaths for many years on a variety of projects. We are based in Southwold, just inside the AONB and it is with this Blythburgh WHITE HART INN Tel: 01502 478217 beautiful location in mind, that we have great respect for London Road, Blythburgh, Suffolk IP19 9LQ the built, social and natural environment around us. Over In partnership with Location: Village Restaurant/dining room Yes several years we have been working hard to make our Garden/courtyard Yes Bar meals Yes impact on the environment a positive one, please visit our Children welcome Yes Accommodation Yes website to discover some of the things we’ve been up to. Disabled access Yes Dogs welcome Yes Parking available Yes Credit cards welcome Yes We often talk about that “ah, that’s better” moment and what better way to celebrate that, than walking one of these routes and stopping off at an Adnams pub for some well-earned refreshment. We’d love to hear your thoughts on the walk (and the pub!), please upload your comments and photos to our website adnams.co.uk.” Andy Wood, Adnams Chief Executive You can follow us on Lowestoft Beccles twitter.com/adnams More Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB pub walks Southwold 01 Pin Mill 08 Aldeburgh 02 Levington 09 Eastbridge 03 Waldringfield 10 Westleton 04 Woodbridge 11 Walberswick 05 Butley 12 Southwold 06 Orford 13 Wrentham 07 Snape 14 Blythburgh Aldeburgh Woodbridge Sea Ipswich Blythburgh Church North In partnership with Felixstowe Harwich 14 Blythburgh Further information Main walk – 2.5 miles/3.8 km Blythburgh Suffolk Coast and Heaths AONB This scenic 2.5 mile walk follows the River Blyth downstream Tel: 01394 384948 www.suffolkcoastandheaths.org From the White Hart Inn A , turn right towards Walberswick, following the river wall, before returning via East of England Tourism towards the bridge then right again down the Blythburgh village. -

Wenhaston with Mells Neighbourhood Plan

Wenhaston with Mells Hamlet Parish Council Neighbourhood Development Plan 2015 to 2030 MADE July 2018 Page Intentionally Blank Page 2 of 76 WwMNDP/Made July 2018 ABSTRACT Wenhaston with Mells Hamlet Parish Council has decided to undertake the process of producing a Neighbourhood Development Plan, as defined in the Localism Act 2011. This plan is to create a vision for the development and use of land within Wenhaston with Mells from 2015 to 2030 in accordance with the majority views of the residents of the area. Our Neighbourhood Plan contains the Policies and Strategies that will help to realise the Community’s vision for Wenhaston with Mells Parish and address key issues that have been raised during the extensive engagement undertaken with the community and identified through the plan making process. The Policies are the essential components of our Plan and the Strategies represent community aspirations that the Parish Council and other stakeholders should endeavour to address. They are based on sound analysis and a strong evidence base. They align with the National Planning Policy Framework, National Planning Guidance and the strategic planning context set by Suffolk Coastal District Council. They will contribute towards sustainable development and are compatible with EU regulations. Once the Plan is made (adopted) by Suffolk Coastal District Council, the Policies will become part of the Development Plan for the area and a statutory consideration in determining all planning applications. Policies are shown in blue boxes. Strategies form part of the Neighbourhood Development Plan. They are activities identified in the feedback from the community and these will be managed by the Parish Council over the Plan period. -

Halesworth New Reach Trail

The New Reach is a section of waterway that passes through the Lane and the town centre. 2 with the silting of Southwold centre of Halesworth. It once formed part of the Blyth Navigation, There were once commercial harbour, that sounded the death which ran for seven miles from Halesworth to the port of buildings here, and looking knell for the Blyth Navigation, Southwold. The Navigation was constructed in the middle of the towards River Lane you can see when heavy haulage moved from 1700s, following the course of the River Blyth. Sections were canals to railways which were straightened and dredged, new lengths dug parallel to the river, where there was a cut to take faster and more efficient. Go banks strengthened, and five new locks were built. The wherries to George Maltings, construction was financed by businessmen who wanted to which have now been converted through the gate and join the all- develop commercial traffic in and out of the growing industrial to housing. The steps from the weather track. After 100m, go HALESWORTH and market town of Halesworth. towpath into the Reach were through another gate on your left installed for canoeists in 1992. and pass under a small railway NEW REACH THE TRAIL This spot also marks the arch (no. 462) which opens onto beginning of the Millennium Blyth Meadow where cows graze START AT THE WOODEN between the New Reach and the TRAIL Green, some 50 acres of open in summer. The Reach is on your FOOTBRIDGE BY BLYTH MEWS Town River which itself forms space that was acquired by a left and re-joins the Town River. -

CB Clke 97 * VILE, NIGEL. Pub Walks Along the Kennet & Avon Canal

RCHS BIBILIOGRAPHY PROJECT BIBLIOGRAPHY OF PERIODICAL LITERATURE OF INLAND WATERWAY TRANSPORT HISTORY Updated 27.10.18. Please send additions/corrections/comments to Grahame Boyes, [email protected]. This bibliography is arranged by class, as defined in the following table. It can be searched by calling up the FIND function (Control + F) and then entering the class or a keyword/phrase. Note that, to aid searching, some entries have also been given a subsidiary classification at the end. CLASSIFICATION SCHEME CA GENERAL HISTORY AND DESCRIPTION OF INLAND WATERWAY TRANSPORT IN THE BRITISH ISLES CB INLAND WATERWAY TRANSPORT AT PARTICULAR PERIODS CB1 Antiquity and early use of inland navigation up to c.1600 (arranged by region of the British Isles) CB1z Boats CB2 c.1600–1750 The age of river improvement schemes CB3 c.1750–1850 The Canal Age CB4 c.1850–1947 The period of decline CB5 1948– Nationalisation and after; the rebirth of canals as leisure amenities CC INLAND WATERWAY TRANSPORT IN PARTICULAR REGIONS OF THE BRITISH ISLES CC1a England—Southern England CC1b England—South West region CC1c England—South East region CC1cl London CC1d England—West Midlands region CC1e England—East Midlands region CC1f England—East Anglia CC1fq England—East Anglia: guides CC1g England—Northern England CC1h England—North West region CC1i England—Yorkshire and North Humberside region CC1j England—North region CC2 Scotland CC3 Wales CC4 Ireland CC4L Ireland: individual canals and navigations CC4Lbal Ballinamore & Ballyconnel Canal and Shannon–Erne Waterway CC4Lban Lower and Upper Bann Navigations and Lough Neagh CC4Lbar Barrow Navigation CC4Lboy Boyne Navigation CC4Lcor Corrib Navigation, including the Eglinton Canal and Cong Canal CC4Ldub Dublin & Kingstown Ship Canal (proposed) CC4Lern Erne Navigation CC4Lgra Grand Canal, including the County of Kildare Canal CC4Llag Lagan Navigation CC4Llif R. -

Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Longstanton, Cambridgeshire

ArchaeologicalArchaeological Test Pit Excavations Test Pit Excavations in Blythburgh, in Longstanton, CambridgeshireSuffolk, 2015 2017 &- 20192017 Catherine Collins 1 2 Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Blythburgh, Suffolk in 2017, 2018 and 2019 Catherine Collins 2019 Access Cambridge Archaeology Department of Archaeology University of Cambridge Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QG 01223 761519 [email protected] http://www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk/ (Front cover images. Left: BLY/17/12 working shot. Right: BLY/18/2 group shot. Copyright ACA) 3 4 Contents 1 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... 11 2 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 13 2.1 ACCESS CAMBRIDGE ARCHAEOLOGY .................................................................................... 13 2.2 THE INDEPENDENT LEARNING ARCHAEOLOGY FIELD SCHOOL (ILAFS) ............................... 13 2.3 TEST-PIT EXCAVATION AND RURAL SETTLEMENT STUDIES .................................................. 14 3 AIMS, OBJECTIVES AND DESIRED OUTCOMES ............................................................. 15 3.1 AIMS ...................................................................................................................................... 15 3.2 OBJECTIVES .......................................................................................................................... -

Blyth Valley Experience

Walking and Wildlife Activities Design oddities & Ancient structures There are beautiful churches too... The Blyth Valley Calendar the High points of the Blyth Valley year include: Church Trail: Highlights East to West, include:- April Bluebell Walks, Henham Walking the myriad paths and Cycling - The Blyth Valley is The Balancing Barn 14 - tracks is the optimum way to dissected by National Cycle May High Tide Festival of new theatre Blyth An extraordinary example of Holy Trinity Church, Blythburgh - writing (nationally acclaimed) explore this timeless landscape. Route 1 (see map). Moreover contemporary architecture 'The Cathedral of the Marshes'. Beer Festival, Laxfield Follow criss-crossing trails the mesh of winding single- tucked away in Thorington Perhaps Suffolk's most iconic church Wings & Wheels, Henham across Halesworth’s Millennium track country lanes is just opposite the church. It is the with its fine location, stunning Valley Green (the largest in England) or perfect for leisurely bike brain-child of Living proportions and famed painted June Suffolk Open Studios pick up one of the charming rides – for example, the Architecture, a charity dedicated to promoting world-class angels decorating the ceiling. July The Halesworth Food and Craft Fair circular walks between circular Halesworth Wheel examples of modern architecture in settings where the Latitude Festival, Henham Experience Halesworth and the villages of can be joined at any of public can get up close (and even hire for holidays!). Heveningham Hall Country Fair Holton, Chediston or Wenhaston. several points (see map). RIBA Award winner. www.living-architecture.co.uk St Peter's Church, Wenhaston - July - Sept The Cratfield Concerts where the journey is the destination Linear walkways shadow the A unique medieval Doom painting.