Twop Community 53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3.16: the U.S

The West Wing Weekly 3.16: The U.S. Poet Laureate Guests: Tara Ariano, Sarah D. Bunting, and David Wade [Intro Music] JOSH: Hi friends. You’re listening to the West Wing Weekly. I’m Joshua Malina. HRISHI: And I’m Hrishikesh Hirway. Today we’re talking about “The U.S. Poet Laureate”. It’s Season 3, Episode 16. JOSH: The teleplay is by Aaron Sorkin. The story by Laura Glasser. And this episode was directed by Christopher Misiano. It first aired on March 27th, 2002. HRISHI: I wanted to read the synopsis from Warner Brothers because there is a puzzling thing in it. JOSH: A Warnopsis, ok. HRISHI: And the Warner Brothers synopsis gets syndicated other places so it’s not an isolated thing. Here it is: Bartlet makes a disparaging comment about a potential Republican nominee after a television interview not realizing that he is still being recorded. For days, CJ must control the scandal and Sam recalls Republican White House Legal Counsel, Ainsley Hayes, from vacation, to help formulate the administration’s official response. Meanwhile, Toby tries to dissuade the newly named U.S. Poet Laureate, Tabatha Fortis, from publicly objecting to the government’s lack of support for a treaty on landmines. Bartlet ponders saving a failing computer company, and Josh is both repulsed and intrigued by the fact that there is a fan-based website devoted to him. JOSH: The first thing that hit me was just it’s a lie. They’re protecting the integrity of the episode but they say that Bartlet does not realize that he is still being filmed. -

January 2011 Prizes and Awards

January 2011 Prizes and Awards 4:25 P.M., Friday, January 7, 2011 PROGRAM SUMMARY OF AWARDS OPENING REMARKS FOR AMS George E. Andrews, President BÔCHER MEMORIAL PRIZE: ASAF NAOR, GUNTHER UHLMANN American Mathematical Society FRANK NELSON COLE PRIZE IN NUMBER THEORY: CHANDRASHEKHAR KHARE AND DEBORAH AND FRANKLIN TEPPER HAIMO AWARDS FOR DISTINGUISHED COLLEGE OR UNIVERSITY JEAN-PIERRE WINTENBERGER TEACHING OF MATHEMATICS LEVI L. CONANT PRIZE: DAVID VOGAN Mathematical Association of America JOSEPH L. DOOB PRIZE: PETER KRONHEIMER AND TOMASZ MROWKA EULER BOOK PRIZE LEONARD EISENBUD PRIZE FOR MATHEMATICS AND PHYSICS: HERBERT SPOHN Mathematical Association of America RUTH LYTTLE SATTER PRIZE IN MATHEMATICS: AMIE WILKINSON DAVID P. R OBBINS PRIZE LEROY P. S TEELE PRIZE FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT: JOHN WILLARD MILNOR Mathematical Association of America LEROY P. S TEELE PRIZE FOR MATHEMATICAL EXPOSITION: HENRYK IWANIEC BÔCHER MEMORIAL PRIZE LEROY P. S TEELE PRIZE FOR SEMINAL CONTRIBUTION TO RESEARCH: INGRID DAUBECHIES American Mathematical Society FOR AMS-MAA-SIAM LEVI L. CONANT PRIZE American Mathematical Society FRANK AND BRENNIE MORGAN PRIZE FOR OUTSTANDING RESEARCH IN MATHEMATICS BY AN UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT: MARIA MONKS LEONARD EISENBUD PRIZE FOR MATHEMATICS AND OR PHYSICS F AWM American Mathematical Society LOUISE HAY AWARD FOR CONTRIBUTIONS TO MATHEMATICS EDUCATION: PATRICIA CAMPBELL RUTH LYTTLE SATTER PRIZE IN MATHEMATICS M. GWENETH HUMPHREYS AWARD FOR MENTORSHIP OF UNDERGRADUATE WOMEN IN MATHEMATICS: American Mathematical Society RHONDA HUGHES ALICE T. S CHAFER PRIZE FOR EXCELLENCE IN MATHEMATICS BY AN UNDERGRADUATE WOMAN: LOUISE HAY AWARD FOR CONTRIBUTIONS TO MATHEMATICS EDUCATION SHERRY GONG Association for Women in Mathematics ALICE T. S CHAFER PRIZE FOR EXCELLENCE IN MATHEMATICS BY AN UNDERGRADUATE WOMAN FOR JPBM Association for Women in Mathematics COMMUNICATIONS AWARD: NICOLAS FALACCI AND CHERYL HEUTON M. -

Adler, Mccarthy Engulfed in WWII 'Fog' - Variety.Com 1/4/10 12:03 PM

Adler, McCarthy engulfed in WWII 'Fog' - Variety.com 1/4/10 12:03 PM http://www.variety.com/index.asp?layout=print_story&articleid=VR1118013143&categoryid=13 To print this page, select "PRINT" from the File Menu of your browser. Posted: Mon., Dec. 28, 2009, 8:00pm PT Adler, McCarthy engulfed in WWII 'Fog' Producers option sci-fi horror comicbook 'Night and Fog' By TATIANA SIEGEL Producers Gil Adler and Shane McCarthy have optioned the sci-fi horror comicbook "Night and Fog" from publisher Studio 407. No stranger to comicbook-based material, Adler has produced such graphic-based fare as "Constantine," "Superman Returns" and the upcoming Brandon Routh starrer "Dead of Night," which is based on the popular Italian title "Dylan Dog." This material is definitely in my strike zone in more ways than one," Adler said, noting his prior role as a producer of such horror projects as the "Tales From the Crypt" series. "But what really appealed to me wasn't so much the genre trappings but rather the characters that really drive this story." Set during WWII, story revolves around an infectious mist unleashed on a military base that transforms its victims into preternatural creatures of the night. But when the survivors try to kill them, they adapt and change into something even more horrific and unstoppable. Studio 407's Alex Leung will also serve as a producer on "Night and Fog." Adler and McCarthy are also teaming to produce an adaptation of "Havana Nocturne" along with Eric Eisner. They also recently optioned Ken Bruen's crime thriller "Tower." "Night and Fog" is available in comic shops in the single-issue format and digitally on iPhone through Comixology. -

Prize Is Awarded Every Three Years at the Joint Mathematics Meetings

AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY LEVI L. CONANT PRIZE This prize was established in 2000 in honor of Levi L. Conant to recognize the best expository paper published in either the Notices of the AMS or the Bulletin of the AMS in the preceding fi ve years. Levi L. Conant (1857–1916) was a math- ematician who taught at Dakota School of Mines for three years and at Worcester Polytechnic Institute for twenty-fi ve years. His will included a bequest to the AMS effective upon his wife’s death, which occurred sixty years after his own demise. Citation Persi Diaconis The Levi L. Conant Prize for 2012 is awarded to Persi Diaconis for his article, “The Markov chain Monte Carlo revolution” (Bulletin Amer. Math. Soc. 46 (2009), no. 2, 179–205). This wonderful article is a lively and engaging overview of modern methods in probability and statistics, and their applications. It opens with a fascinating real- life example: a prison psychologist turns up at Stanford University with encoded messages written by prisoners, and Marc Coram uses the Metropolis algorithm to decrypt them. From there, the article gets even more compelling! After a highly accessible description of Markov chains from fi rst principles, Diaconis colorfully illustrates many of the applications and venues of these ideas. Along the way, he points to some very interesting mathematics and some fascinating open questions, especially about the running time in concrete situ- ations of the Metropolis algorithm, which is a specifi c Monte Carlo method for constructing Markov chains. The article also highlights the use of spectral methods to deduce estimates for the length of the chain needed to achieve mixing. -

Balboa Observer-Picayune, Television Without Pity, and the Audiovisual Translator

Balboa Observer-Picayune, Television without Pity, and the Audiovisual Translator: Two Case Studies of Seeking Information among Online Fan Communities Aino Pellonperä University of Tampere Department of Modern Languages and Translation Studies Translation Studies (English) Pro gradu thesis April 2008 Tampereen yliopisto Käännöstiede (englanti) Kieli- ja käännöstieteiden laitos PELLONPERÄ, AINO: Balboa Observer-Picayune, Television without Pity and the Audiovisual Translator: Two Case Studies of Seeking Information among Online Fan Communities Pro gradu -tutkielma, 80 sivua + liitteet 6 sivua + suomenkielinen lyhennelmä 7 sivua Kevät 2008 Tutkielmassa käsiteltiin kahta yhdysvaltalaista televisiosarjaa ja miten näiden epäviralliset internetfaniyhteisöt keräävät sarjaan liittyvää tietoa, mikä saattaisi auttaa audiovisuaalisia kääntäjiä heidän työssään. Tapaustutkimuksina olivat kaksi televisiosarja-internetsivusto- paria: Sukuvika (Arrested Development) ja Balboa Observer-Picayune -kotisivu, ja Veronica Mars ja Television without Pity -keskusteluryhmä. Tutkielman lähtökohtana oli oletus, että internetsivustoilla televisiosarjoista kerätään ja keskustellaan mitä erinäisimpiä asioita, ja että audiovisuaaliset kääntäjät voivat hyötyä näistä aktiviteeteista. Oletusta pohjustettiin esittämällä tiedonhankintatapoja Savolaisen, Ellisin, Wilsonin, Marchioninin ja Choon malleista. Näin osoitettiin, että audiovisuaaliset kääntäjät hyötyvät “lupaavissa tietoympäristöissä”. Schäffnerin, Neubertin ja Beebyn et al. käännöspätevyyden malleista etsittiin -

Numb3rs Episode Guide Episodes 001–118

Numb3rs Episode Guide Episodes 001–118 Last episode aired Friday March 12, 2010 www.cbs.com c c 2010 www.tv.com c 2010 www.cbs.com c 2010 www.redhawke.org c 2010 vitemo.com The summaries and recaps of all the Numb3rs episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http://www. cbs.com and http://www.redhawke.org and http://vitemo.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on June 28, 2017 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.59 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 Uncertainty Principle . .5 3 Vector ..............................................7 4 Structural Corruption . .9 5 Prime Suspect . 11 6 Sabotage . 13 7 Counterfeit Reality . 15 8 Identity Crisis . 17 9 Sniper Zero . 19 10 Dirty Bomb . 21 11 Sacrifice . 23 12 Noisy Edge . 25 13 Man Hunt . 27 Season 2 29 1 Judgment Call . 31 2 Bettor or Worse . 33 3 Obsession . 37 4 Calculated Risk . 39 5 Assassin . 41 6 Soft Target . 43 7 Convergence . 45 8 In Plain Sight . 47 9 Toxin............................................... 49 10 Bones of Contention . 51 11 Scorched . 53 12 TheOG ............................................. 55 13 Double Down . 57 14 Harvest . 59 15 The Running Man . 61 16 Protest . 63 17 Mind Games . 65 18 All’s Fair . 67 19 Dark Matter . 69 20 Guns and Roses . 71 21 Rampage . 73 22 Backscatter . 75 23 Undercurrents . 77 24 Hot Shot . 81 Numb3rs Episode Guide Season 3 83 1 Spree ............................................. -

Moniek Van Der Kallen. 0209082

Moniek van der Kallen Master thesis Film and Television Sciences Utrecht Tutor: Ansje van Beusekom Second reader: Rob Leurs Reader with English as first language: Andy McKenzie How to end the season of a formulaic series. A comparative analysis of the series HOUSE MD and VERONICA MARS about the recurring conflict in the narrative lines of television series’ season finales: resolution versus continuity. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT.…………………………....………………………..…..1 KEYWORDS………………………………………………………...1 INTRODUCTION.……………………..………………………..…..2 METHOD ……………………………………..…………………......4 Story levels ……………..………….…………………………………………...….4 The WOW-method………………………….…………………………..……….…5 The story steps of the Ruven & Batavier Schedule ……………………………….6 THEORY: SERIES, SERIALS AND SOAP OPERAS …………..8 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF SOAP OPERAS ………….....…………...…………....14 Narrative subjects ………………………………………………..……..………...14 Narrative structures ….............……………………………………..…………….15 The organization of time ........................................................................................16 1. NARRATIVE STRATEGIES IN HOUSE MD ...…………..…19 EPISODE 1.01 PILOT. Building expectations for the series ..........................................19 Characteristics of a pilot of a series. Introducing the characters, creating expectations…………………………………..………………..……......19 Story endings…..…………………………………..……………………….…....24 Promises for future conflict……….………………..…………………………….26 EPISODE 1.22 THE HONEYMOON. Starting new narratives instead of ending them..27 Introduction a new romantic narrative, -

Key Agents of Mediation That Define, Create, and Maintain TV Fandom

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication Fall 12-20-2012 Abracadabra: Key Agents of Mediation that Define, Create, and Maintain TV Fandom David H. Gardner Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Recommended Citation Gardner, David H., "Abracadabra: Key Agents of Mediation that Define, Create, and Maintain TV Fandom." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/95 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABRACADABRA: KEY AGENTS OF MEDIATION THAT DEFINE, CREATE, AND MAINTAIN TV FANDOM by DAVID H. GARDNER Under the Direction of Dr. Alisa Perren ABSTRACT From a media industries, fan studies, and emerging socio-cultural public relations perspective, this project pulls back the Hollywood curtain to explore two questions: 1) How do TV public relations practitioners and key tastemaker/gatekeeper media define, create, build, and maintain fandom?; and 2) How do they make meaning of fandom and their agency/role in fan creation from their position of industrial producers, cultural intermediaries, members of the audience, and as fans themselves? This project brings five influential, working public relations and media professionals into a conversation about two case studies from the 2010-2011 television season – broadcast network CBS’ Hawaii Five-0 and basic cable network AMC’s The Walking Dead. Each of these shows speaks to fandom in particular ways and are representative of the industry’s current approaches in luring specific audiences to TV. -

PDF Download the Numbers Behind Numb3rs: Solving Crime with Mathematics Ebook, Epub

THE NUMBERS BEHIND NUMB3RS: SOLVING CRIME WITH MATHEMATICS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Professor Keith Devlin,Gary Lorden | 243 pages | 27 Apr 2009 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780452288577 | English | New York, NY, India The Numbers Behind Numb3rs: Solving Crime with Mathematics PDF Book Nicolas Falacci Cheryl Heuton. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Archived from the original on August 2, The discussions about prime numbers and encryption were especially interesting and I only wish there were updates to this book, which is 11 years old. Retrieved September 9, June 7, [15]. This is a fascinating look at how math is used in crime-fighting. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Larry sells his home and assumes a nomadic lifestyle, while he becomes romantically involved with Megan. Cast and crew commentaries for five episodes, "Crunching Numb3rs: Season 3," a mini-documentary of the Eppes house, a blooper reel, and a tour of the Eppes' house set. Other research interests include: theory of information, models of reasoning, applications of mathematical techniques in the study of communication, and mathematical cognition. Share this book Facebook. Charlie and Don learn that Alan has lost a substantial amount of money in his k. Well, I decided to finally just return this books as I wasn't getting very far. Feb 02, Steven rated it did not like it Shelves: toread , mathematics. The authors use real life examples of when math was used to crack open an investigation as well as elaborate on the techiques used in the Television show. Archived from the original on November 16, The book was somewhat dry in its presentation of the material. -

Grey's Anatomy 101 : Seattle Grace, Unauthorized / Edited by Leah Wilson

GREY’S ANATOMY 101 OTHER TITLES IN THE SMART POP SERIES Taking the Red Pill Seven Seasons of Buffy Five Seasons of Angel What Would Sipowicz Do? Stepping through the Stargate The Anthology at the End of the Universe Finding Serenity The War of the Worlds Alias Assumed Navigating the Golden Compass Farscape Forever! Flirting with Pride and Prejudice Revisiting Narnia Totally Charmed King Kong Is Back! Mapping the World of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice The Unauthorized X-Men The Man from Krypton Welcome to Wisteria Lane Star Wars on Trial The Battle for Azeroth Boarding the Enterprise Getting Lost James Bond in the 21st Century So Say We All Investigating CSI Literary Cash Webslinger Halo Effect Neptune Noir Coffee at Luke’s Perfectly Plum GREY’S ANATOMY 101 S EATTLE G RACE,UNAUTHORIZED Edited by Leah Wilson BENBELLA BOOKS, INC. Dallas, Texas THIS PUBLICATION HAS NOT BEEN PREPARED, APPROVED, OR LICENSED BY ANY ENTITY THAT CREATED OR PRODUCED THE WELL-KNOWN TELEVISION SERIES GREY’S ANATOMY. “I Want to Write for Grey’s” © 2007 by Kristin Harmel “If Addison Hadn’t Returned, Would Derek and Meredith Have Made It as a Couple?” © 2007 by Carly Phillips “Why Drs. Grey and Shepherd Will Never Live Happily Ever After” © 2007 by Elizabeth Engstrom “‘We Don’t Do Well with Mothers Here’” © 2007 by Beth Macias “Grey’s Anatomy and the New Man” © 2007 by Todd Gilchrist “Diagnostic Notes, Case Histories, and Profiles of Acute Hybridity in Grey’s Anatomy” © 2007 by Sarah Wendell “Sex in Seattle” © 2007 by Jacqueline Carey “Love Stinks” © 2007 by Eileen Rendahl “Drawing the Line” © 2007 by Janine Hiddlestone “Brushing Up on Your Bedside Manner” © 2007 by Erin Dailey “Finding the Hero” © 2007 by Lawrence Watt-Evans “Next of Kin” © 2007 by Melissa Rayworth “Only the Best for Cristina Yang” © 2007 by Robert Greenberger “What Would Bailey Do?” © 2007 by Lani Diane Rich “Walking a Thin Line” © 2007 by Tanya Michna “Shades of Grey” © 2007 by Yvonne Jocks “Anatomy of Twenty-First Century Television” © 2007 by Kevin Smokler Additional Materials © BenBella Books, Inc. -

1-3 Front CFP 1-25-10.Indd 2 1/25/10 1:34:22 PM

Area/State Colby Free Press Monday, January 22, 2010 Page 3 Weather Policy puts a dent in tardies Corner From “TARDIES,” Page 1 the 2008-2009 audit. Staats said • Activities Director Larry Ga- the audit found no violations and bel said the work on a constitution tations are made in front of both there was actually an increase in for the Great Western Athletics classes. unencumbered cash. Staats said Conference is mostly fi nished. • Katherine Kaus, Paige Roop- the district does not currently have There has been a lot of work done chan, Katrina Kaus, Kayla Hock- excessive debt. on scheduling and the document is ersmith and Morgan Bell present- “From what I’m seeing, the dis- at a place where the district can ac- ed some of their Spanish projects. trict is taking appropriate actions,” cept it, he said. It is not fi nal, but The class took the Spanish Three he said. it is a good guide for next years’ Kings Day, celebrated on Jan. 6, Staats recommended closing sports seasons. and put together decorative proj- any student activity funds that • The board approved Feb. 26 as ects detailing the holiday tradi- haven’t had any activity. Those Adequate Yearly Progress Incen- tions. funds might be for activities that tive Day. Since the district met all National Weather Service • Brian Staats of Adams, are no longer put on by the school, of the progress goals for the year, Tonight: Clear, with a low Brown, Beran and Ball presented he said. school will be cancelled that day. around 14. -

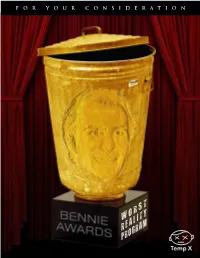

Worst Reality Program PROGRAM TITLE LOGLINE NETWORK the Vexcon Pest Removal Team Helps to Rid Clients of Billy the Exterminator A&E Their Extreme Pest Cases

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION WORST REALITY PROGRAM PROGRAM TITLE LOGLINE NETWORK The Vexcon pest removal team helps to rid clients of Billy the Exterminator A&E their extreme pest cases. Performance series featuring Criss Angel, a master Criss Angel: Mindfreak illusionist known for his spontaneous street A&E performances and public shows. Reality series which focuses on bounty hunter Duane Dog the Bounty Hunter "Dog" Chapman, his professional life as well as the A&E home life he shares with his wife and their 12 children. A docusoap following the family life of Gene Simmons, Gene Simmons Family Jewels which include his longtime girlfriend, Shannon Tweed, a A&E former Playmate of the Year, and their two children. Reality show following rock star Dee Snider along with Growing Up Twisted A&E his wife and three children. Reality show that follows individuals whose lives have Hoarders A&E been affected by their need to hoard things. Reality series in which the friends and relatives of an individual dealing with serious problems or addictions Intervention come together to set up an intervention for the person in A&E the hopes of getting his or her life back on track. Reality show that follows actress Kirstie Alley as she Kirstie Alley's Big Life struggles with weight loss and raises her two daughters A&E as a single mom. Documentary relaity series that follows a Manhattan- Manhunters: Fugitive Task Force based federal task that tracks down fugitives in the Tri- A&E state area. Individuals with severe anxiety, compulsions, panic Obsessed attacks and phobias are given the chance to work with a A&E therapist in order to help work through their disorder.