Leadership, Values and the Peranakans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Immigrant Parenting in the United States and Singapore

genealogy Article Challenges and Strategies for Promoting Children’s Education: A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Immigrant Parenting in the United States and Singapore Min Zhou 1,* and Jun Wang 2 1 Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551, USA 2 School of Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore 639818, Singapore; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 February 2019; Accepted: 11 April 2019; Published: 15 April 2019 Abstract: Confucian heritage culture holds that a good education is the path to upward social mobility as well as the road to realizing an individual’s fullest potential in life. In both China and Chinese diasporic communities around the world, education is of utmost importance and is central to childrearing in the family. In this paper, we address one of the most serious resettlement issues that new Chinese immigrants face—children’s education. We examine how receiving contexts matter for parenting, what immigrant parents do to promote their children’s education, and what enables parenting strategies to yield expected outcomes. Our analysis is based mainly on data collected from face-to-face interviews and participant observations in Chinese immigrant communities in Los Angeles and New York in the United States and in Singapore. We find that, despite different contexts of reception, new Chinese immigrant parents hold similar views and expectations on children’s education, are equally concerned about achievement outcomes, and tend to adopt overbearing parenting strategies. We also find that, while the Chinese way of parenting is severely contested in the processes of migration and adaptation, the success in promoting children’s educational excellence involves not only the right set of culturally specific strategies but also tangible support from host-society institutions and familial and ethnic social networks. -

Narratives of the Dayak People of Sarawak, Malaysia Elizabeth Weinlein '17 Pitzer College

EnviroLab Asia Volume 1 Article 6 Issue 1 Justice, Indigeneity, and Development 2017 Indigenous People, Development and Environmental Justice: Narratives of the Dayak People of Sarawak, Malaysia Elizabeth Weinlein '17 Pitzer College Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/envirolabasia Part of the Anthropology Commons, Asian History Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Geography Commons, Policy History, Theory, and Methods Commons, Religion Commons, Social Policy Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Weinlein, Elizabeth '17 (2017) "Indigenous People, Development and Environmental Justice: Narratives of the Dayak People of Sarawak, Malaysia," EnviroLab Asia: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/envirolabasia/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in EnviroLab Asia by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Indigenous People, Development and Environmental Justice: Narratives of the Dayak People of Sarawak, Malaysia Cover Page Footnote Elizabeth Weinlein graduated from Pitzer College in 2017, double majoring in Environmental Policy and Asian Studies. For the next year, she has committed to working with the Americorps -

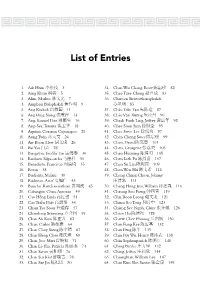

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Long Way Home

24 WacanaWacana Vol. Vol. 18 No.18 No. 1 (2017): 1 (2017) 24-37 Long way home The life history of Chinese-Indonesian migrants in the Netherlands1 YUMI KITAMURA ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to trace the modern history of Indonesia through the experience of two Chinese Indonesians who migrated to the Netherlands at different periods of time. These life stories represent both postcolonial experiences and the Cold War politics in Indonesia. The migration of Chinese Indonesians since the beginning of the twentieth century has had long history, however, most of the previous literature has focused on the experiences of the “Peranakan” group who are not representative of various other groups of Chinese Indonesian migrants who have had different experiences in making their journey to the Netherlands. This paper will present two stories as a parallel to the more commonly known narratives of the “Peranakan” experience. KEYWORDS September 30th Movement; migration; Chinese Indonesians; cultural revolution; China; Curacao; the Netherlands. 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this paper is to trace the modern history of Indonesia through the experience of Chinese Indonesians who migrated to the Netherlands after World War II. The study of overseas Chinese tends to challenge the boundaries of the nation-state by exploring the ideas of transnational identities 1 Some parts of this article are based on the rewriting of a Japanese article: Kitamura, Yumi. 2014. “Passage to the West; The life history of Chinese Indonesians in the Netherlands“ (in Japanese), Chiiki Kenkyu 14(2): 219-239. Yumi Kitamura is an associate professor at the Kyoto University Library. -

Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee by Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S

4 Spotlight Remembering Dr Goh Keng Swee By Kwa Chong Guan (1918–2010) Head of External Programmes S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Nanyang Technological University Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong declared in his eulogy at other public figures in Britain, the United States or China, the state funeral for Dr Goh Keng Swee that “Dr Goh was Dr Goh left no memoirs. However, contained within his one of our nation’s founding fathers.… A whole generation speeches and interviews are insights into how he wished of Singaporeans has grown up enjoying the fruits of growth to be remembered. and prosperity, because one of our ablest sons decided to The deepest recollections about Dr Goh must be the fight for Singapore’s independence, progress and future.” personal memories of those who had the opportunity to How do we remember a founding father of a nation? Dr interact with him. At the core of these select few are Goh Keng Swee left a lasting impression on everyone he the members of his immediate and extended family. encountered. But more importantly, he changed the lives of many who worked alongside him and in his public career initiated policies that have fundamentally shaped the destiny of Singapore. Our primary memories of Dr Goh will be through an awareness and understanding of the post-World War II anti-colonialist and nationalist struggle for independence in which Dr Goh played a key, if backstage, role until 1959. Thereafter, Dr Goh is remembered as the country’s economic and social architect as well as its defence strategist and one of Lee Kuan Yew’s ablest and most trusted lieutenants in our narrating of what has come to be recognised as “The Singapore Story”. -

News Release for Immediate Release

News Release For Immediate Release Singapore brings a slice of colourful Peranakan culture to MIPTV 2009 Singapore, 20 March 2009 – Amidst a strong line-up of animation content and factual titles will be a slice of Peranakan 1 culture at international trade show MIPTV in Cannes, France this year. MediaCorp artistes Qi Yuwu and Jeanette Aw of The Little Nyonya will join the Singapore delegation at one of the world’s largest fairs for the buying and selling of audiovisual content to promote the 34-episode serial. Revolving around the trials and tribulations of a woman born of Straits-born Chinese or Peranakan heritage, the drama weaves Peranakan culture into its storyline, and brings to life some of the more intriguing aspects of this ethnic group. It became Singapore’s most- watched drama in 15 years when it aired late last year. The lead actors of the drama join a 10-company strong delegation at MIPTV to promote for sale and distribution a slate of 41 titles under the Singapore Pavilion, led by the Media Development Authority of Singapore (MDA). Headlining the slate is a strong line-up of animation co-productions, including three titles making their market debut. These include Dinosaur Train which is Big Communications’ collaboration with The Jim Henson Company, and supported by MDA. A children’s programme, Dinosaur Train has secured sales in Norway and Canada, with broadcasters from Nickelodeon Australia, Germany's Super RTL and 1 For centuries, the riches of Southeast Asia have brought foreign traders to the region. While many returned to their homelands, some remained behind, marrying local women. -

Btsisi', Blandas, and Malays

BARBARA S. NOWAK Massey University SINGAN KN÷N MUNTIL Btsisi’, Blandas, and Malays Ethnicity and Identity in the Malay Peninsula Based on Btsisi’ Folklore and Ethnohistory Abstract This article examines Btsisi’ myths, stories, and ethnohistory in order to gain an under- standing of Btsisi’ perceptions of their place in Malaysia. Three major themes run through the Btsisi’ myths and stories presented in this paper. The first theme is that Austronesian-speaking peoples have historically harassed Btsisi’, stealing their land, enslaving their children, and killing their people. The second theme is that Btsisi’ are different from their Malay neighbors, who are Muslim; and, following from the above two themes is the third theme that Btsisi’ reject the Malay’s Islamic ideal of fulfilment in pilgrimage, and hence reject their assimilation into Malay culture and identity. In addition to these three themes there are two critical issues the myths and stories point out; that Btsisi’ and other Orang Asli were original inhabitants of the Peninsula, and Btsisi’ and Blandas share a common origin and history. Keywords: Btsisi’—ethnic identity—origin myths—slaving—Orang Asli—Peninsular Malaysia Asian Folklore Studies, Volume 63, 2004: 303–323 MA’ BTSISI’, a South Aslian speaking people, reside along the man- grove coasts of the Kelang and Kuala Langat Districts of Selangor, HWest Malaysia.1* Numbering approximately two thousand (RASHID 1995, 9), Btsisi’ are unique among Aslian peoples for their coastal location and for their geographic separation from other Austroasiatic Mon- Khmer speakers. Btsisi’, like other Aslian peoples have encountered histori- cally aggressive and sometimes deadly hostility from Austronesian-speaking peoples. -

I N T H E S P I R I T O F S E R V I

The Old Frees’ AssOCIatION, SINGAPORE Registered 1962 Live Free IN THE SPIRIT OF SERVING Penang Free School 1816-2016 Penang Free School in August 2015. The Old Frees’ AssOCIatION, SINGAPORE Registered 1962 www.ofa.sg Live Free IN THE SPIRIT OF SERVING AUTHOR Tan Chung Lee PUBLISHER The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore PUBLISHER The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore 3 Mount Elizabeth #11-07, Mount Elizabeth Medical Centre Singapore 228510 AUTHOR Tan Chung Lee OFAS COFFEE-TABLE BOOK ADJUDICATION PANEL John Lim Kok Min (co-chairman) Tan Yew Oo (co-chairman) Kok Weng On Lee Eng Hin Lee Seng Teik Malcolm Tan Ban Hoe OFAS COFFEE-TABLE BOOK WORKGROUP Alex KH Ooi Cheah Hock Leong The OFAS Management Committee would like to thank Gabriel Teh Choo Thok Editorial Consultant: Tan Chung Lee the family of the late Chan U Seek and OFA Life Members Graphic Design: ST Leng Production: Inkworks Media & Communications for their donations towards the publication of this book. Printer: The Phoenix Press Sdn Bhd 6, Lebuh Gereja, 10200 Penang, Malaysia The committee would also like to acknowledge all others who PHOTOGRAPH COPYRIGHT have contributed to and assisted in the production of this Penang Free School Archives Lee Huat Hin aka Haha Lee, Chapter 8 book; it apologises if it has inadvertently omitted anyone. Supreme Court of Singapore (Judiciary) Family of Dr Wu Lien-Teh, Chapter 7 Tan Chung Lee Copyright © 2016 The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of The Old Frees’ Association, Singapore. -

National Day Awards 2019

1 NATIONAL DAY AWARDS 2019 THE ORDER OF TEMASEK (WITH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Temasek (Dengan Kepujian)] Name Designation 1 Mr J Y Pillay Former Chairman, Council of Presidential Advisers 1 2 THE ORDER OF NILA UTAMA (WITH HIGH DISTINCTION) [Darjah Utama Nila Utama (Dengan Kepujian Tinggi)] Name Designation 1 Mr Lim Chee Onn Member, Council of Presidential Advisers 林子安 2 3 THE DISTINGUISHED SERVICE ORDER [Darjah Utama Bakti Cemerlang] Name Designation 1 Mr Ang Kong Hua Chairman, Sembcorp Industries Ltd 洪光华 Chairman, GIC Investment Board 2 Mr Chiang Chie Foo Chairman, CPF Board 郑子富 Chairman, PUB 3 Dr Gerard Ee Hock Kim Chairman, Charities Council 余福金 3 4 THE MERITORIOUS SERVICE MEDAL [Pingat Jasa Gemilang] Name Designation 1 Ms Ho Peng Advisor and Former Director-General of 何品 Education 2 Mr Yatiman Yusof Chairman, Malay Language Council Board of Advisors 4 5 THE PUBLIC SERVICE STAR (BAR) [Bintang Bakti Masyarakat (Lintang)] Name Designation Chua Chu Kang GRC 1 Mr Low Beng Tin, BBM Honorary Chairman, Nanyang CCC 刘明镇 East Coast GRC 2 Mr Koh Tong Seng, BBM, P Kepujian Chairman, Changi Simei CCC 许中正 Jalan Besar GRC 3 Mr Tony Phua, BBM Patron, Whampoa CCC 潘东尼 Nee Soon GRC 4 Mr Lim Chap Huat, BBM Patron, Chong Pang CCC 林捷发 West Coast GRC 5 Mr Ng Soh Kim, BBM Honorary Chairman, Boon Lay CCMC 黄素钦 Bukit Batok SMC 6 Mr Peter Yeo Koon Poh, BBM Honorary Chairman, Bukit Batok CCC 杨崐堡 Bukit Panjang SMC 7 Mr Tan Jue Tong, BBM Vice-Chairman, Bukit Panjang C2E 陈维忠 Hougang SMC 8 Mr Lien Wai Poh, BBM Chairman, Hougang CCC 连怀宝 Ministry of Home Affairs -

Contact Languages: Ecology and Evolution in Asia

This page intentionally left blank Contact Languages Why do groups of speakers in certain times and places come up with new varieties of languages? What are the social settings that determine whether a mixed language, a pidgin, or a Creole will develop, and how can we under- stand the ways in which different languages contribute to the new grammar? Through the study of Malay contact varieties such as Baba and Bazaar Malay, Cocos Malay, and Sri Lanka Malay, as well as the Asian Portuguese ver- nacular of Macau, and China Coast Pidgin, the book explores the social and structural dynamics that underlie the fascinating phenomenon of the creation of new, or restructured, grammars. It emphasizes the importance and inter- play of historical documentation, socio-cultural observation, and linguistic analysis in the study of contact languages, offering an evolutionary frame- work for the study of contact language formation – including pidgins and Creoles – in which historical, socio-cultural, and typological observations come together. umberto ansaldo is Associate Professor in Linguistics at the University of Hong Kong. He was formerly a senior researcher and lecturer with the Amsterdam Center for Language and Communication at the University of Amsterdam. He has also worked in Sweden and Singapore and conducted fieldwork in China, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Christmas Island, and Sri Lanka. He is the co-editor of the Creole Language Library Series and has co-edited various journals and books including Deconstructing Creole (2007). Cambridge Approaches to Language Contact General Editor Salikoko S. Mufwene, University of Chicago Editorial Board Robert Chaudenson, Université d’Aix-en-Provence Braj Kachru, University of Illinois at Urbana Raj Mesthrie, University of Cape Town Lesley Milroy, University of Michigan Shana Poplack, University of Ottawa Michael Silverstein, University of Chicago Cambridge Approaches to Language Contact is an interdisciplinary series bringing together work on language contact from a diverse range of research areas. -

<H1>The English Governess at the Siamese Court by Anna Harriette

The English Governess At The Siamese Court by Anna Harriette Leonowens The English Governess At The Siamese Court by Anna Harriette Leonowens E-text prepared by Lee Dawei, Michelle Shephard, David Moynihan, Charles Franks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team THE ENGLISH GOVERNESS AT THE SIAMESE COURT BEING RECOLLECTIONS OF SIX YEARS IN THE ROYAL IN THE ROYAL PALACE AT BANGKOK BY ANNA HARRIETTE LEONOWENS. With Illustrations, FROM PHOTOGRAPHS PRESENTED TO THE AUTHOR BY THE KING OF SIAM. page 1 / 369 [Illustration: Gateway Of the Old Palace.] TO MRS. KATHERINE S. COBB. I have not asked your leave, dear friend, to dedicate to you these pages of my experience in the heart of an Asiatic court; but I know you will indulge me when I tell you that my single object in inscribing your name here is to evince my grateful appreciation of the kindness that led you to urge me to try the resources of your country instead of returning to Siam, and to plead so tenderly in behalf of my children. I wish the offering were more worthy of your acceptance. But to associate your name with the work your cordial sympathy has fostered, and thus pleasantly to retrace even the saddest of my recollections, amid the happiness that now surrounds me,--a happiness I owe to the generous friendship of noble-hearted American women,--is indeed a privilege and a compensation. I remain, with true affection, gratitude, and admiration, Your friend, A. H. L. 26th July, 1870. page 2 / 369 PREFACE. His Majesty, Somdetch P'hra Paramendr Maha Mongkut, the Supreme King of Siam, having sent to Singapore for an English lady to undertake the education of his children, my friends pointed to me. -

Balestier Heritage Trail Booklet

BALESTIER HERITAGE TRAIL A COMPANION GUIDE DISCOVER OUR SHARED HERITAGE OTHER HERITAGE TRAILS IN THIS SERIES ANG MO KIO ORCHARD BEDOK QUEENSTOWN BUKIT TIMAH SINGAPORE RIVER WALK JALAN BESAR TAMPINES JUBILEE WALK TIONG BAHRU JURONG TOA PAYOH KAMPONG GLAM WORLD WAR II LITTLE INDIA YISHUN-SEMBAWANG 1 CONTENTS Introduction 2 Healthcare and Hospitals 45 Tan Tock Seng Hospital Early History 3 Middleton Hospital (now Development and agriculture Communicable Disease Centre) Joseph Balestier, the first Former nurses’ quarters (now American Consul to Singapore Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine) Dover Park Hospice After Balestier 9 Ren Ci Community Hospital Balestier Road in the late 1800s Former School Dental Clinic Country bungalows Handicaps Welfare Association Homes at Ah Hood Road Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital Tai Gin Road and the Sun Yat The National Kidney Foundation Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall Eurasian enclave and Kampong Houses of Faith 56 Chia Heng Goh Chor Tua Pek Kong Temple Shophouses and terrace houses Thong Teck Sian Tong Lian Sin Sia Former industries Chan Chor Min Tong and other former zhaitang Living in Balestier 24 Leng Ern Jee Temple SIT’s first housing estate at Fu Hup Thong Fook Tak Kong Lorong Limau Maha Sasanaramsi Burmese Whampoe Estate, Rayman Buddhist Temple Estate and St Michael’s Estate Masjid Hajjah Rahimabi The HDB era Kebun Limau Other developments in the Church of St Alphonsus 1970s and 1980s (Novena Church) Schools Seventh-Day Adventist Church Law enforcement Salvation Army Balestier Corps Faith Assembly of God Clubs and