World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloads/Hydro2010.Pdf (Accessed on 19 September 2016)

sustainability Review Sustainable Ecosystem Services Framework for Tropical Catchment Management: A Review N. Zafirah 1, N. A. Nurin 1, M. S. Samsurijan 2, M. H. Zuknik 1, M. Rafatullah 1 and M. I. Syakir 1,3,* 1 School of Industrial Technology, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Penang, Malaysia; zafi[email protected] (N.Z.); [email protected] (N.A.N.); [email protected] (M.H.Z.); [email protected] (M.R.) 2 School of Social Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Penang, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Centre for Global Sustainability Studies, (CGSS), Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Penang, Malaysia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +604-653-2110 Academic Editors: Phoebe Koundouri and Ebun Akinsete Received: 6 February 2017; Accepted: 28 March 2017; Published: 4 April 2017 Abstract: The monsoon season is a natural phenomenon that occurs over the Asian continent, bringing extra precipitation which causes significant impact on most tropical watersheds. The tropical region’s countries are rich with natural rainforests and the economies of the countries situated within the region are mainly driven by the agricultural industry. In order to fulfill the agricultural demand, land clearing has worsened the situation by degrading the land surface areas. Rampant land use activities have led to land degradation and soil erosion, resulting in implications on water quality and sedimentation of the river networks. This affects the ecosystem services, especially the hydrological cycles. Intensification of the sedimentation process has resulted in shallower river systems, thus increasing their vulnerability to natural hazards (i.e., climate change, floods). Tropical forests which are essential in servicing their benefits have been depleted due to the increase in human exploitation. -

J. Collins Malay Dialect Research in Malysia: the Issue of Perspective

J. Collins Malay dialect research in Malysia: The issue of perspective In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 145 (1989), no: 2/3, Leiden, 235-264 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 12:15:07AM via free access JAMES T. COLLINS MALAY DIALECT RESEARCH IN MALAYSIA: THE ISSUE OF PERSPECTIVE1 Introduction When European travellers and adventurers began to explore the coasts and islands of Southeast Asia almost five hundred years ago, they found Malay spoken in many of the ports and entrepots of the region. Indeed, today Malay remains an important indigenous language in Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, Thailand and Singapore.2 It should not be a surprise, then, that such a widespread and ancient language is characterized by a wealth of diverse 1 Earlier versions of this paper were presented to the English Department of the National University of Singapore (July 22,1987) and to the Persatuan Linguistik Malaysia (July 23, 1987). I would like to thank those who attended those presentations and provided valuable insights that have contributed to improving the paper. I am especially grateful to Dr. Anne Pakir of Singapore and to Dr. Nik Safiah Karim of Malaysia, who invited me to present a paper. I am also grateful to Dr. Azhar M. Simin and En. Awang Sariyan, who considerably enlivened the presentation in Kuala Lumpur. Professor George Grace and Professor Albert Schiitz read earlier drafts of this paper. I thank them for their advice and encouragement. 2 Writing in 1881, Maxwell (1907:2) observed that: 'Malay is the language not of a nation, but of tribes and communities widely scattered in the East.. -

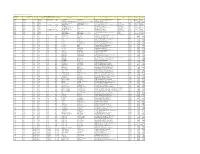

Soalan No : 93 Pemberitahuan Pertanyaan Dewan Rakyat Mesyuarat Ketiga, Penggal Ketiga Parlimen Keempat Belas Pertanyaan : Bukan

SOALAN NO : 93 PEMBERITAHUAN PERTANYAAN DEWAN RAKYAT MESYUARAT KETIGA, PENGGAL KETIGA PARLIMEN KEEMPAT BELAS PERTANYAAN : BUKAN LISAN DARIPADA : TUAN CHA KEE CHIN [RASAH] SOALAN TUAN CHA KEE CHIN [ RASAH ] minta MENTERI KESIHATAN menyatakan senarai jumlah pesakit positif COVID-19 dan kematian akibat jangkitan COVID-19 di Negeri Sembilan mengikut daerah dan mukim. JAWAPAN Tuan Yang di-Pertua, 1. Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia (KKM) ingin memaklumkan sehingga 29 November 2020, kumulatif kes positif COVID-19 yang dilaporkan di Malaysia adalah sebanyak 64,485 kes. Daripada jumlah tersebut, Negeri Sembilan mencatatkan sebanyak 4,774 kes (7.4% daripada keseluruhan kes di Malaysia). Di Negeri Sembilan, kebanyakan kes dilaporkan dari daerah Seremban dan mukim Ampangan. Perincian jumlah kes mengikut daerah dan mukim Negeri Sembilan adalah Seremban (3,973 kes), Rembau (416 kes), Port Dickson (275 kes), Kuala Pilah (34 kes), Tampin (33 kes), Jempol (27 kes) dan Jelebu (16 kes). 2. Pecahan mengikut mukim bagi daerah Seremban adalah seperti berikut: i. Ampangan 1,432 kes; ii. Labu 1,133 kes; iii. Seremban 600 kes; iv. Rantau 358 kes; v. Rasah 277 kes; vi. Setul 151 kes; SOALAN NO : 93 vii. Lenggeng 22 kes; dan viii. Pantai 0 kes. 3. Pecahan mengikut mukim bagi daerah Port Dickson adalah seperti berikut: i. Jimah 110 kes; ii. Si Rusa 135 kes; iii. Port Dickson 19 kes; iv. Linggi 7 kes; dan v. Pasir Panjang 4 kes. 4. Pecahan mengikut mukim bagi daerah Jempol adalah seperti berikut: i. Rompin 8 kes; ii. Kuala jempol 6 kes; iii. Serting Ilir 6 kes; iv. Jelai 5 kes; dan v. Serting ulu 2 kes. -

Australians Into Battle : the Ambush at Gema S

CHAPTER 1 1 AUSTRALIANS INTO BATTLE : THE AMBUSH AT GEMA S ENERAL Percival had decided before the debacle at Slim River G that the most he could hope to do pending the arrival of further reinforcements at Singapore was to hold Johore. This would involve giving up three rich and well-developed areas—the State of Selangor (includin g Kuala Lumpur, capital of the Federated Malay States), the State of Negr i Sembilan, and the colony of Malacca—but he thought that Kuala Lumpu r could be held until at least the middle of January . He intended that the III Indian Corps should withdraw slowly to a line in Johore stretching from Batu Anam, north-west of Segamat, on the trunk road and railway , to Muar on the west coast, south of Malacca . It should then be respon- sible for the defence of western Johore, leaving the Australians in thei r role as defenders of eastern Johore. General Bennett, however, believing that he might soon be called upo n for assistance on the western front, had instituted on 19th December a series of reconnaissances along the line from Gemas to Muar . By 1st January a plan had formed in his mind to obtain the release of his 22nd Brigade from the Mersing-Jemaluang area and to use it to hold the enem y near Gemas while counter-attacks were made by his 27th Brigade on the Japanese flank and rear in the vicinity of Tampin, on the main road near the border of Malacca and Negri Sembilan . Although he realised tha t further coastal landings were possible, he thought of these in terms of small parties, and considered that the enemy would prefer to press forwar d as he was doing by the trunk road rather than attempt a major movement by coastal roads, despite the fact that the coastal route Malacca-Muar- Batu Pahat offered a short cut to Ayer Hitam, far to his rear . -

The State with a Vision

The state with a vision By NISSHANTHAN DHANAPALAN NEGRI Sembilan has more to offer industries make up the bulk of the produce such as paddy and catfish than just its rich culture and Negri Sembilan's GDP. Industrial aquaculture as well as its small history. It is an amalgamation of a areas such as the Nilai Industrial condiments and handicraft multicultural society with its Estate, techpark@enstek, Pedas businesses. signature Minangkabau culture Halal Park and Senawang Negri Sembilan offers many that has been the pride of the state Industrial Park are some of the other attractions such as the for decades. many industrial areas set up to Centipede Temple, Gunung Angsi In addition, Negri Sembilan is provide investors with strategic and Gunung Besar Hantu hiking known for its culinary signature locations for business. spots, Pedas hot springs and ostrich cuisine such as gulai masak cili api, Industrial estates within Negri farms in Port Dickson and Jelebu. beef noodles and siew pau as well Sembilan are close to amenities These attractions are slowly as its beaches and resorts in Port and services such as the Kuala changing the landscape of Negri Dickson a favourite getaway Lumpur International Airport Sembilan's tourism sector. destination for many city dwellers (KLIA), Port Klang, Cyberjaya, Residential haven in the Klang Valley. Putrajaya and Kuala Lumpur, The announcement of the giving business owners the benefit Negri Sembilan shares much of Malaysia Vision Valley has placed of not only cheaper overheads but the same development as the the magnifying glass over the state also effective transportation Klang Valley thanks to access to infrastructure such as the and its potential in contributing to means. -

Negeri Ppd Kod Sekolah Nama Sekolah Alamat Bandar Poskod Telefon Fax Negeri Sembilan Ppd Jempol/Jelebu Nea0025 Smk Dato' Undang

SENARAI SEKOLAH MENENGAH NEGERI SEMBILAN KOD NEGERI PPD NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT BANDAR POSKOD TELEFON FAX SEKOLAH PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA0025 SMK DATO' UNDANG MUSA AL-HAJ KM 2, JALAN PERTANG, KUALA KLAWANG JELEBU 71600 066136225 066138161 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD SMK DATO' UNDANG SYED ALI AL-JUFRI, NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA0026 BT 4 1/2 PERADONG SIMPANG GELAMI KUALA KLAWANG 71600 066136895 066138318 JEMPOL/JELEBU SIMPANG GELAMI PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6001 SMK BAHAU KM 3, JALAN ROMPIN BAHAU 72100 064541232 064542549 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6002 SMK (FELDA) PASOH 2 FELDA PASOH 2 SIMPANG PERTANG 72300 064961185 064962400 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6003 SMK SERI PERPATIH PUSAT BANDAR PALONG 4,5 & 6, GEMAS 73430 064666362 064665711 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6005 SMK (FELDA) PALONG DUA FELDA PALONG 2 GEMAS 73450 064631314 064631173 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6006 SMK (FELDA) LUI BARAT BANDAR SERI JEMPOL 72120 064676300 064676296 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6007 SMK (FELDA) PALONG 7 FELDA PALONG TUJUH GEMAS 73470 064645464 064645588 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6008 SMK (FELDA) BANDAR BARU SERTING BANDAR SERI JEMPOL 72120 064581849 064583115 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6009 SMK SERTING HILIR KOMPLEKS FELDA SERTING HILIR 4 72120 064684504 064683165 JEMPOL/JELEBU JEMPOL PPD NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6010 SMK PALONG SEBELAS (FELDA) FELDA PALONG SEBELAS GEMAS 73430 064669751 064669751 JEMPOL/JELEBU PPD BANDAR SERI NEGERI SEMBILAN NEA6011 SMK SERI JEMPOL -

Anthropogenic Land Use Patterns in the Malay Peninsula During the British Colonial Era

Anthropogenic land use patterns in the Malay peninsula during the British colonial era Nor Rasidah Hashim & Mohd Shahrudin Abdul Manan Faculty of Environmental Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia 1 GISHS09. 7-10 October 2009. Academia Sinica, Taiwan Study background & objective • Using GIS to analyze the colonial land use/ landscape changes in the Malay peninsula in the early half of the 20th century (1907-1938). • Our case study focuses on the British period before and through WW1 and right before WW2, i.e., a mature phase of British rule in the peninsula. • Initial expectation: Some land use especially forest clearing and agriculture in the peninsula’s inland area but did not know specifics. • Approach was exploratory (Just do it!). • Research started in 2007. 2 GISHS09. 7-10 October 2009. Academia Sinica, Taiwan Methods Study area Map by Godinho de Eredia, 1613 Important in ancient trade 3 GISHS09. 7-10 October 2009. Academia Sinica, Taiwan Historical Database of Penarikan • Between 1519 – 1613 there were at least 53 maps depicting the transpeninsular route / river. But only de Eredia’s 1613 map got it right, i.e. showing a land portage (Wheatley, 1961). • The last written record of a transpeninsular trip using Penarikan was by Daly (1875). 4 5 Methods 1907 Map LEGENDS • Railways • Metalled Roads & Paths • Cart roads and paths • Rivers & Streams • Trigonometical stations • Hills Fixed by Intersection • Alienated land … agricultural • Alienated land … Mining • State boundary • District boundary • Town boundary • Rest houses • Halting -

Jualan FAMA Kedah Ketika PKP Cecah RM11.88 Juta

AUTHOR: No author available SECTION: NASIONAL PAGE: 25 PRINTED SIZE: 195.00cm² REGION: KL MARKET: Malaysia PHOTO: Full Color ASR: MYR 4,134.00 ITEM ID: MY0039598832 02 MAY, 2020 Jualan FAMA Kedah ketika PKP cecah RM11.88 juta Sinar Harian, Malaysia Page 1 of 2 Jualan FAMA Kedah ketika PKP cecah RM11.88 juta BALING - Lembaga Pemasa- masaran, FAMA telah mem buat Penyerahan disempurnakan ran Pertanian Persekutuan belian melebihi 80 peratus hasil Ahli Parlimen Baling, Datuk (FAMA) Kedah berjaya men- keluaran petani dan berjaya Seri Abdul Azeez Abdul Ra- capai nilai jualan mencecah membuat 333 pengaturan pa- him. RM11.88 juta membabitkan saran. Isa berkata, setakat ini Ke- Pasar Segar Terkawal di negeri “Tiada isu lambakan berlaku dah mempunyai enam Pasar itu sepanjang Perintah Kawalan di Kedah walaupun dalam tem- Segar Terkawal yang diluluskan Pergerakan (PKP). poh PKP kerana FAMA telah beroperasi semasa tempoh PKP Pengarah FAMA Kedah, Isa berjaya memasarkan lebih 80 dengan prosedur operasi Hamzah berkata, jumlah itu peratus hasil petani,” katanya standard ditetapkan antaranya adalah hasil jualan kepada ketika hadir ke sesi penyerahan di Guar Chempedak, Changlun, 189,826 orang pengguna anta- sumbangan Kombo Ramadan Kuala Kedah, Kulim, Pusat ra 18 Mac hingga 19 April petugas barisan hadapan di Ibu Operasi FAMA Alor Setar dan Isa (dua dari kanan) memantau penghantaran 300 pek Kombo Ramadan yang 2020. Pejabat Polis Daerah (IPD) Ba- Pusat Operasi FAMA Sungai dibeli Abdul Azeez (kiri) untuk diagihkan kepada petugas di IPD Baling semalam. Menurutnya, dari segi pe- ling di sini semalam. Petani. Provided for client's internal research purposes only. May not be further copied, distributed, sold or published in any form without the prior consent of the copyright owner. -

The Provider-Based Evaluation (Probe) 2014 Preliminary Report

The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE) 2014 Preliminary Report I. Background of ProBE 2014 The Provider-Based Evaluation (ProBE), continuation of the formerly known Malaysia Government Portals and Websites Assessment (MGPWA), has been concluded for the assessment year of 2014. As mandated by the Government of Malaysia via the Flagship Coordination Committee (FCC) Meeting chaired by the Secretary General of Malaysia, MDeC hereby announces the result of ProBE 2014. Effective Date and Implementation The assessment year for ProBE 2014 has commenced on the 1 st of July 2014 following the announcement of the criteria and its methodology to all agencies. A total of 1086 Government websites from twenty four Ministries and thirteen states were identified for assessment. Methodology In line with the continuous and heightened effort from the Government to enhance delivery of services to the citizens, significant advancements were introduced to the criteria and methodology of assessment for ProBE 2014 exercise. The year 2014 spearheaded the introduction and implementation of self-assessment methodology where all agencies were required to assess their own websites based on the prescribed ProBE criteria. The key features of the methodology are as follows: ● Agencies are required to conduct assessment of their respective websites throughout the year; ● Parents agencies played a vital role in monitoring as well as approving their agencies to be able to conduct the self-assessment; ● During the self-assessment process, each agency is required to record -

Negeri Sembilan

MALAYSIA LAPORAN SURVEI PENDAPATAN ISI RUMAH DAN KEMUDAHAN ASAS MENGIKUT NEGERI DAN DAERAH PENTADBIRAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME AND BASIC AMENITIES SURVEY REPORT BY STATE AND ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT NEGERI SEMBILAN 2019 Pemakluman/Announcement: Kerajaan Malaysia telah mengisytiharkan Hari Statistik Negara (MyStats Day) pada 20 Oktober setiap tahun. Tema sambutan MyStats Day 2020 adalah “Connecting The World With Data We Can Trust”. The Government of Malaysia has declared National Statistics Day (MyStats Day) on 20th October each year. MyStats Day theme is “Connecting The World With Data We Can Trust”. JABATAN PERANGKAAN MALAYSIA DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS, MALAYSIA Diterbitkan dan dicetak oleh/Published and printed by: Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia Department of Statistics, Malaysia Blok C6, Kompleks C Pusat Pentadbiran Kerajaan Persekutuan 62514 Putrajaya MALAYSIA Tel. : 03-8885 7000 Faks : 03-8888 9248 Portal : https://www.dosm.gov.my Facebook/Twitter/Instagram : StatsMalaysia Emel/Email : [email protected] (pertanyaan umum/general enquiries) [email protected] (pertanyaan & permintaan data/data request & enquiries) Harga/Price : RM30.00 Diterbitkan pada July 2020/Published on July 2020 Hakcipta terpelihara/All rights reserved. Tiada bahagian daripada terbitan ini boleh diterbitkan semula, disimpan untuk pengeluaran atau ditukar dalam apa-apa bentuk atau alat apa jua pun kecuali setelah mendapat kebenaran daripada Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia. Pengguna yang mengeluarkan sebarang maklumat dari terbitan ini sama ada yang asal atau diolah semula hendaklah meletakkan kenyataan berikut: “Sumber: Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia” No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means or stored in data base without the prior written permission from Department of Statistics, Malaysia. -

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations

BELLCORE PRACTICE BR 751-401-180 ISSUE 16, FEBRUARY 1999 COMMON LANGUAGE® Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY This document contains proprietary information that shall be distributed, routed or made available only within Bellcore, except with written permission of Bellcore. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE Possession and/or use of this material is subject to the provisions of a written license agreement with Bellcore. Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BR 751-401-180 Copyright Page Issue 16, February 1999 Prepared for Bellcore by: R. Keller For further information, please contact: R. Keller (732) 699-5330 To obtain copies of this document, Regional Company/BCC personnel should contact their company’s document coordinator; Bellcore personnel should call (732) 699-5802. Copyright 1999 Bellcore. All rights reserved. Project funding year: 1999. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. ii LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-180 Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Issue 16, February 1999 Trademark Acknowledgements Trademark Acknowledgements COMMON LANGUAGE is a registered trademark and CLLI is a trademark of Bellcore. BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE iii Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations BR 751-401-180 Trademark Acknowledgements Issue 16, February 1999 BELLCORE PROPRIETARY - INTERNAL USE ONLY See proprietary restrictions on title page. iv LICENSED MATERIAL - PROPERTY OF BELLCORE BR 751-401-180 Geographical Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Issue 16, February 1999 Table of Contents COMMON LANGUAGE Geographic Codes Countries of the World & Unique Locations Table of Contents 1.