Notulae Nomenclaturales 46–59

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phleum Alpinum L

Phleum alpinum L. Alpine Cat’s-tail A scarce alpine grass with distinctive purplish flower heads, long bristly awns and short, broad and glabrous leaves. It is associated with base- rich flushes and mires, more rarely with rocky habitats, and occasionally with weakly acid substrates enriched by flushing with base-rich water. In Britain it is more or less confined to above 610 m northern and central Scotland with two southern outliers in the North Pennines. It is assessed as of Least Concern in Great Britain, but in England it is assessed as Critically Endangered, due to very restricted numbers and recent decline. ©Pete Stroh IDENTIFICATION limit for both these species (540 m) is well below the lower limit for P. alpinum in Britain (610 m). However, P. pratense Phleum alpinum is a shortly rhizomatous, loosely tufted has been recorded as an introduction at 845 m near to the P. perennial alpine grass with short, broad, glabrous leaves (-6 alpinum on Great Dun Fell (Pearman & Corner 2004). mm) and short, blunt ligules (0.5–2 mm; Cope & Gray 2009). The uppermost leaf sheath is inflated. Alopecurus magellanicus, with which it often grows, has hairy, awnless glumes and ‘thunder-cloud’ coloured flower- The inflorescences are dark-blue or brownish purple, oval to heads (red-purple in P. alpinum; Raven & Walters 1956). oblong shaped (10-50 mm). The spikelets are purplish with long awns (2-3 mm) and the keels are fringed with stiff white bristles. HABITATS Phleum alpinum is a montane grass of open, rocky habitats or SIMILAR SPECIES of closed swards on base-rich substrates, or occasionally on more acidic materials enriched by flushing or down-washed Phleum alpinum is told from P. -

The Rock Garden 136 the Ro

January 2016 January 2016 THE ROCK GARDEN 136 THE ROCK GARDEN 136 January 2016 THE ROCK GARDEN Volume XXXIV Part 3 - 136 January 2016 THE ROCK GARDEN Volume XXXIV Part 3 - 136 PostalPostal Subscriptions Subscriptions from from 1st October, 1st October, 2015 2015 Postal subscriptionsPostal subscriptions are payable are payable annually annually by October by October and provide and provide membership membership of the of the SRGC untilSRGC 30 thuntil September 30th September of the following of the following year. year. SubscriptionSubscription Rates Rates UK UK OverseasOverseas Single annualSingle annual £18 £18 £23 £23 Junior Junior £3 £3 £7 £7 (under 18(under on 1 18st Oct) on 1st Oct) Family Family £21 £21 £25 £25 (Two adults(Two andadults up and to two up childrento two children under 18 under on 1 18st Oct) on 1st Oct) Three yearThree subscriptions year subscriptions are available are available at three at times three the times above the aboveannual annualrates. Renewals rates. Renewals for threefor year three subscriptions year subscriptions may only may be only made be atmade the end at the of endthe three of the year three period. year period. All subscriptionAll subscription payments payments to the club to the must club be must made be inmade GB Pounds in GB Pounds Sterling. Sterling. ChequesCheques should shouldbe made be payablemade payable to ‘The Scottishto ‘The Scottish Rock Garden Rock Garden Club’ and Club’ must and be must be drawn ondrawn a UK on bank. a UK bank. SubscriptionSubscription payments payments may be may made be throughmade through the post the by post Visa byor MastercardVisa or Mastercard providingproviding the following the following information information is sent: is sent: The longThe number long number on the cardon the card The nameThe ofname the cardholder of the cardholder as shown as onshown the cardon the card The cardThe expiry card date expiry date The cv2The 3 digit cv2 number3 digit number (from back (from of back the card) of the card) The cardholder’sThe cardholder’s signature. -

Savory Guide

The Herb Society of America's Essential Guide to Savory 2015 Herb of the Year 1 Introduction As with previous publications of The Herb Society of America's Essential Guides we have developed The Herb Society of America's Essential The Herb Society Guide to Savory in order to promote the knowledge, of America is use, and delight of herbs - the Society's mission. We hope that this guide will be a starting point for studies dedicated to the of savory and that you will develop an understanding and appreciation of what we, the editors, deem to be an knowledge, use underutilized herb in our modern times. and delight of In starting to put this guide together we first had to ask ourselves what it would cover. Unlike dill, herbs through horseradish, or rosemary, savory is not one distinct species. It is a general term that covers mainly the educational genus Satureja, but as time and botanists have fractured the many plants that have been called programs, savories, the title now refers to multiple genera. As research and some of the most important savories still belong to the genus Satureja our main focus will be on those plants, sharing the but we will also include some of their close cousins. The more the merrier! experience of its Savories are very historical plants and have long been utilized in their native regions of southern members with the Europe, western Asia, and parts of North America. It community. is our hope that all members of The Herb Society of America who don't already grow and use savories will grow at least one of them in the year 2015 and try cooking with it. -

G.C. Oeder's Conflict with Linnaeus and the Implementation of Taxonomic and Nomenclatural Ideas in the Monumental Flora Danica

Gardens’ Bulletin Singapore 71(Suppl. 2):53-85. 2019 53 doi: 10.26492/gbs71(suppl. 2).2019-07 G.C. Oeder’s conflict with Linnaeus and the implementation of taxonomic and nomenclatural ideas in the monumental Flora Danica project (1761–1883) I. Friis Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK–2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark. [email protected] ABSTRACT. Hitherto unpublished parts of the history of the Icones … Florae Danicae (1761–1883), one of the largest illustrated botanical works published, are analysed; it covered the entire flora of the double monarchy of Denmark–Norway, Schleswig and Holstein and the North Atlantic dependencies. A study of the little noticed taxonomic and nomenclatural principles behind the Icones is presented. G.C. Oeder, founder of the project, approved the ideas of Buffon and Haller and rejected Linnaean binary nomenclature because of its lack of stability of genera. In the Icones …, Oeder cited all names used for each plant in chronological order, with the binary Linnaean name last, to which principle Linnaeus reacted. By the end of the 18th century, Linnaean nomenclature had become standard, apart from in Flora Danica and a very few other botanical works. Applying Linnaean nomenclature elsewhere, O.F. Müller, editor 1775–1782, and M. Vahl, editor 1787–1799, followed Oeder’s norm in the Icones. J.W. Hornemann, editor 1810–1840, followed Oeder in his first fascicles, but began experimenting with changes towards Linnaean nomenclature from 1810. After 1840, subsequent editors consistently applied Linnaean principles for accepted names and synonyms. Keywords. Accepted names, genera, natural classification, species, synonymy Introduction In his excellent monograph on how the Linnaean reforms gained general acceptance among botanists, Stafleu (1971: 260) specifically stated that he left out a discussion of C.G. -

Maynooth University Publications 2018 Peer Reviewed Journal Name Department Affiliations Journal Pub Title Authors

Maynooth University Publications 2018 Peer Reviewed Journal Name Department Affiliations Journal Pub Title Authors DR LAURA ANDERSON MUSIC - MUSIC AND LETTERS Sonic ‘detheatricalisation’: Jean Cocteau, Film Music, and 'Les Parents terribles' Laura Anderson DR ALBERTO ARRIBAS SOCIOLOGY - Current Sociology Reframing the public sociology debate: Towards collaborative and decolonial praxis. Arribas Lozano, A. Knowledge co-production with social movement networks. Redefining grassroots DR ALBERTO ARRIBAS SOCIOLOGY - Social Movement Studies politics, rethinking research. Arribas Lozano, A. Migraciones, acción colectiva y colonialidad del saber en el campo académico DR ALBERTO ARRIBAS SOCIOLOGY - - español: los y las migrantes como sujetos políticos invisibles/invisibilizados. Arribas Lozano, A. PROFESSOR LAUREN ARRINGTON ENGLISH - Yeats Annual Fighting Spirits: Yeats, Pound and The Winding Stair (1929) Arrington, Lauren PROFESSOR LAUREN ARRINGTON ENGLISH - Irish Political Studies The Blindness of Hindsight: Irish and British Poets Reflect on Early Fascist Italy Arrington, Lauren Histoire et Civilisation du Livre. Revue « Rebelle malgré lui » - récits de réconciliation et de réintégration dans les MS MONIKA BARGET ARTS & HUMANITIES INSTITUTE - Internationale biographies politiques britanniques du XVIIIe siècle Barget, Monika DR OLIVER BARTLETT LAW - European Journal of Risk Regulation Reforming the Regulation on Spirit Drinks – an Example of Better Regulation? O Bartlett DR OLIVER BARTLETT LAW - European Law Journal Power, Policy Ideas and Paternalism in Non-Communicable Disease Prevention O Bartlett DR BERNHARD BAUER SCHOOL OF CELTIC STUDIES - Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie The Story of the Monk and the Devil Bernhard Bauer The Aspergillus nidulans pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases are essential to integrate Ries L.;de Assis L.;Rodrigues F.;Caldana C.;Rocha M.;Malavazi I.;Bayram DR OZGUR BAYRAM BIOLOGY - G3 (Bethesda, Md.) carbon source metabolism Ö.;Goldman G. -

(Dr. Sc. Nat.) Vorgelegt Der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftl

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 Flowers, sex, and diversity: Reproductive-ecological and macro-evolutionary aspects of floral variation in the Primrose family, Primulaceae de Vos, Jurriaan Michiel Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-88785 Dissertation Originally published at: de Vos, Jurriaan Michiel. Flowers, sex, and diversity: Reproductive-ecological and macro-evolutionary aspects of floral variation in the Primrose family, Primulaceae. 2012, University of Zurich, Facultyof Science. FLOWERS, SEX, AND DIVERSITY. REPRODUCTIVE-ECOLOGICAL AND MACRO-EVOLUTIONARY ASPECTS OF FLORAL VARIATION IN THE PRIMROSE FAMILY, PRIMULACEAE Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Jurriaan Michiel de Vos aus den Niederlanden Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Elena Conti (Vorsitz) Prof. Dr. Antony B. Wilson Dr. Colin E. Hughes Zürich, 2013 !!"#$"#%! "#$%&$%'! (! )*'+,,&$-+''*$.! /! '0$#1'2'! 3! "4+1%&5!26!!"#"$%&'(#)$*+,-)(*#! 77! "4+1%&5!226!-*#)$%.)(#!'&*#!/'%#+'.0*$)/)"$1'(12%-).'*3'0")"$*.)4&4'*#' "5*&,)(*#%$4'+(5"$.(3(-%)(*#'$%)".'(#'+%$6(#7.'2$(1$*.".! 89! "4+1%&5!2226!.1%&&'%#+',!&48'%'9,%#)()%)(5":'-*12%$%)(5"'"5%&,%)(*#'*3' )0"';."&3(#!'.4#+$*1"<'(#'0")"$*.)4&*,.'%#+'0*1*.)4&*,.'2$(1$*.".! 93! "4+1%&5!2:6!$"2$*+,-)(5"'(12&(-%)(*#.'*3'0"$=*!%14'(#'0*1*.)4&*,.' 2$(1$*.".>'5%$(%)(*#'+,$(#!'%#)0".(.'%#+'$"2$*+,-)(5"'%..,$%#-"'(#' %&2(#"'"#5($*#1"#).! 7;7! "4+1%&5!:6!204&*!"#")(-'%#%&4.(.'*3'!"#$%&''."-)(*#'!"#$%&''$"5"%&.' $%12%#)'#*#/1*#*204&4'%1*#!'1*2$0*&*!(-%&&4'+(.)(#-)'.2"-(".! 773! "4+1%&5!:26!-*#-&,+(#!'$"1%$=.! 7<(! +"=$#>?&@.&,&$%'! 7<9! "*552"*?*,!:2%+&! 7<3! !!"#$$%&'#""!&(! Es ist ein zentrales Ziel in der Evolutionsbiologie, die Muster der Vielfalt und die Prozesse, die sie erzeugen, zu verstehen. -

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 5(7), 1301-1312

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 5(7), 1301-1312 Journal Homepage: - www.journalijar.com Article DOI: 10.21474/IJAR01/4841 DOI URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/4841 RESEARCH ARTICLE FLORA OF CHEPAN MOUNTAIN (WESTERN BULGARIA). Dimcho Zahariev. Faculty of Natural Sciences, Department of Plant Protection, Botany and Zoology, University of Shumen, Bulgaria. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Manuscript Info Abstract ……………………. ……………………………………………………………… Manuscript History Chepan Mountain is located in Western Bulgaria. It is part of Balkan Mountains on the territory of Balkan Peninsula in Southern Europe. As Received: 13 May 2017 a result of this study in Chepan Mountain on the territory of only 25 Final Accepted: 15 June 2017 km2 were found 784 species of wild vascular plants from 378 genera Published: July 2017 and 84 families. Such amazing biodiversity can be found in Southern Europe only. The floristic analysis indicates that the most of the Key words:- families and the genera are represented by a small number of inferior Chepan Mountain, floristic analysis, taxa. The hemicryptophytes dominate among the life forms with vascular plants 53.32%. The biological types are represented mainly by perennial herbaceous plants (59.57%). In the flora of the Mountain there are 49 floristic elements. The most of the species are European-Asiatic floristic elements (14.54%), followed by European-Mediterranean floristic elements (13.78%) and subMediterranean floristic elements (13.52%). Among the vascular plants, there are 26 Balkan endemic species, 4 Bulgarian endemic species and 26 relic species. The species with protection statute are 66 species. The anthropophytes among the vascular plants are 390 species (49.74%). -

South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae)

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) Lendel, Anita Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-93287 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Lendel, Anita. South American Cacti in time and space: studies on the diversification of the tribe Cereeae, with particular focus on subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae). 2013, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. South American Cacti in Time and Space: Studies on the Diversification of the Tribe Cereeae, with Particular Focus on Subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae) _________________________________________________________________________________ Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr.sc.nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Anita Lendel aus Kroatien Promotionskomitee: Prof. Dr. H. Peter Linder (Vorsitz) PD. Dr. Reto Nyffeler Prof. Dr. Elena Conti Zürich, 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgments 1 Introduction 3 Chapter 1. Phylogenetics and taxonomy of the tribe Cereeae s.l., with particular focus 15 on the subtribe Trichocereinae (Cactaceae – Cactoideae) Chapter 2. Floral evolution in the South American tribe Cereeae s.l. (Cactaceae: 53 Cactoideae): Pollination syndromes in a comparative phylogenetic context Chapter 3. Contemporaneous and recent radiations of the world’s major succulent 86 plant lineages Chapter 4. Tackling the molecular dating paradox: underestimated pitfalls and best 121 strategies when fossils are scarce Outlook and Future Research 207 Curriculum Vitae 209 Summary 211 Zusammenfassung 213 Acknowledgments I really believe that no one can go through the process of doing a PhD and come out without being changed at a very profound level. -

Apomixis Is Not Prevalent in Subnival to Nival Plants of the European Alps

Annals of Botany 108: 381–390, 2011 doi:10.1093/aob/mcr142, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Apomixis is not prevalent in subnival to nival plants of the European Alps Elvira Ho¨randl1,*, Christoph Dobesˇ2, Jan Suda3,4, Petr Vı´t3,4, Toma´sˇ Urfus3,4, Eva M. Temsch1, Anne-Caroline Cosendai1, Johanna Wagner5 and Ursula Ladinig5 1Department of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna, A-1030 Vienna, Austria, 2Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Vienna, A-1090 Vienna, Austria, 3Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, CZ-128 01 Prague, Czech Republic, 4Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, CZ-252 43 Pru˚honice, Czech Republic and 5Institute of Botany, University of Innsbruck, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] Received: 2 December 2010 Returned for revision: 14 January 2011 Accepted: 28 April 2011 Published electronically: 1 July 2011 † Background and Aims High alpine environments are characterized by short growing seasons, stochastic climatic conditions and fluctuating pollinator visits. These conditions are rather unfavourable for sexual reproduction of flowering plants. Apomixis, asexual reproduction via seed, provides reproductive assurance without the need of pollinators and potentially accelerates seed development. Therefore, apomixis is expected to provide selective advantages in high-alpine biota. Indeed, apomictic species occur frequently in the subalpine to alpine grassland zone of the European Alps, but the mode of reproduction of the subnival to nival flora was largely unknown. † Methods The mode of reproduction in 14 species belonging to seven families was investigated via flow cyto- metric seed screen. -

Disentangling Drivers of Plant Endemism and Diversification

Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 28 (2017) 19–27 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ppees Disentangling drivers of plant endemism and diversification in the European MARK Alps – A phylogenetic and spatially explicit approach ⁎ Jan Smyčkaa, , Cristina Roqueta, Julien Renauda, Wilfried Thuillera, Niklaus E. Zimmermannb, Sébastien Lavergnea a Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine (LECA), 2233 rue de la Piscine, FR-38000 Grenoble, France b Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, Zürcherstrasse 111, CH-8903 Birmensdorf, Switzerland ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Plant endemism in the European Alps is clustered into particular geographic areas. Two contrasted and non Glacial refugia exclusive hypotheses have been suggested to explain these hotspots of endemism: (i) those areas were glacial High elevation refugia, where endemism reflects survival-recolonisation dynamics since the onset of Pleistocene glaciations, (ii) Mountains those are high elevation mountain areas, where endemism was fostered by local speciation events due to geo- Speciation graphic isolation and harsh environmental niches, or by low dispersal ability of inhabiting species. Dispersal Here, we quantitatively compared these two hypotheses using data of species distribution in the European Phylogenetic uncertainty Alps (IntraBioDiv database), species phylogenetic relationships, and species ecological and biological char- acteristics. We developed a spatially and phylogenetically explicit modelling framework to analyze spatial patterns of endemism and the phylogenetic structure of species assemblages. Moreover, we analyzed inter- relations between species trait syndromes and endemism. We found that high endemism occurrs in potential glacial refugia, but only those on calcareous bedrock, and also in areas with high elevation. -

The PDF, Here, Is a Full List of All Mentioned

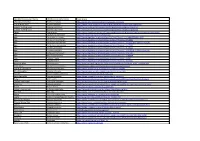

FAUNA Vernacular Name FAUNA Scientific Name Read more a European Hoverfly Pocota personata https://www.naturespot.org.uk/species/pocota-personata a small black wasp Stigmus pendulus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/crabronidae/pemphredoninae/stigmus-pendulus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius concinnus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-concinnus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius nigerrimus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-nigerrimus Adder Vipera berus https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/animals/reptiles-and-amphibians/adder/ Alga Cladophora glomerata https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cladophora Alga Closterium acerosum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=x44d373af81fe4f72 Alga Closterium ehrenbergii https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28183 Alga Closterium moniliferum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28227&sk=0&from=results Alga Coelastrum microporum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27402 Alga Cosmarium botrytis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28326 Alga Lemanea fluviatilis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=32651&sk=0&from=results Alga Pediastrum boryanum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27507 Alga Stigeoclonium tenue https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=60904 Alga Ulothrix zonata https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=562 Algae Synedra tenera https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=34482 -

High-Elevation Limits and the Ecology of High-Elevation Vascular Plants: Legacies from Alexander Von Humboldt1

a Frontiers of Biogeography 2021, 13.3, e53226 Frontiers of Biogeography REVIEW the scientific journal of the International Biogeography Society High-elevation limits and the ecology of high-elevation vascular plants: legacies from Alexander von Humboldt1 H. John B. Birks1,2* 1 Department of Biological Sciences and Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, University of Bergen, PO Box 7803, Bergen, Norway; 2 Ecological Change Research Centre, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1 6BT, UK. *Correspondence: H.J.B. Birks, [email protected] 1 This paper is part of an Elevational Gradients and Mountain Biodiversity Special Issue Abstract Highlights Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland in their • The known uppermost elevation limits of vascular ‘Essay on the Geography of Plants’ discuss what was plants in 22 regions from northernmost Greenland known in 1807 about the elevational limits of vascular to Antarctica through the European Alps, North plants in the Andes, North America, and the European American Rockies, Andes, East and southern Africa, Alps and suggest what factors might influence these upper and South Island, New Zealand are collated to provide elevational limits. Here, in light of current knowledge a global view of high-elevation limits. and techniques, I consider which species are thought to be the highest vascular plants in twenty mountain • The relationships between potential climatic treeline, areas and two polar regions on Earth. I review how one upper limit of closed vegetation in tropical (Andes, can try to