Effective Reading Instruction in Every Classroom, Every Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is Fluency? Adapted From: Elish-Piper, L

NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY | JERRY L. JOHNS LITERACY CLINIC Raising Readers: Tips for Parents What is Fluency? Adapted from: Elish-Piper, L. (2010). Information and ideas for parents about fluency and vocabulary.Illinois Reading Council Journal, 38(2), 48-49. Reading fluency is the ability to read a text easily. Reading mean that children should read as fast as they possibly can. fluency actually has four parts: accuracy, speed, expression and Rate needs to be combined with accuracy, expression and comprehension. Each part is important, but no single part is comprehension to produce fluent reading. Some schools enough on its own. A fluent reader is able to coordinate all four provide a target rate for students in each grade level, usually as aspects of fluency. the number of correct words read per minute. You may wish to ask your child’s teacher if there is a rate goal used for your Accuracy: Reading words correctly is a key to developing fluency. Children need to be able to read words easily without child’s grade level. Those rate targets are important, but they having to stop and decode them by sounding them out or are not the only goal for fluency. For example, if a child reads breaking them into chunks. When children can accurately and very quickly but does not read with expression or understand easily read the words in a text, they are able to think about what what is read, that child is not reading fluently. they are reading rather than putting all of their effort toward Expression: Expression in fluency refers to the ability to read figuring out the words. -

Beginning Reading: Influences on Policy in the United

BEGINNING READING: INFLUENCES ON POLICY IN THE UNITED STATES AND ENGLAND 1998-2010 A Dissertation Submitted to the College of Education of Aurora University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education by Elizabeth Robins April 2010 Beginning Reading: Influences on Policy in the United States and England 1998-2010 by Elizabeth Robins [email protected] Committee members: Ronald Banaszak, Chair Carla Brown, Member Deborah Brotcke, Member Abstract The study investigated the divergence in beginning reading methods between the United States (US) and England from 1998 to 2010. Researchers, policy makers, and publishers were interviewed to explore their knowledge and perceptions concerning how literacy policy was determined. The first three of twelve findings showed that despite the challenges inherent in the political sphere, both governments were driven by low literacy rates to seek greater involvement in literacy education. The intervention was determined by its structure: a central parliamentary system in England, and a federal system of state rights in the US. Three further research-related findings revealed the uneasy relationship existing between policy makers and researchers. Political expediency, the speed of decision making and ideology i also helped shape literacy policy. Secondly, research is viewed differently in each nation. Peer- reviewed, scientifically-based research supporting systematic phonics prevailed in the US, whereas in England additional and more eclectic sources were also included. Thirdly, research showed that educator training in beginning reading was more pervasive and effective in England than the US. English stakeholders proved more knowledgeable about research in the US, whereas little is known about the synthetic phonics approach currently used in England. -

Introduction

1 Introduction Phonics instruction has long been a controversial matter. Emans (1968) points out that the emphasis on phonics instruction has changed several times over the past two centuries. Instruction has shifted from one extreme—no phonics instruction— to the other—phonics instruction as the major method of word-recognition instruction—and back again. Emans also points out that “each time that phonics has been returned to the classroom, it usually has been revised into something quite different from what it was when it was discarded” (p. 607 ). Currently, most beginning reading programs include a significant component of phonics instruc- tion. This is especially true since the implementation of policies related to the No Child Left Behind Act and recommendations by the National Reading Panel (2000) for the use of both instruction and assessments related to explicit pho- nics instruction. It is also likely that the U.S. Department of Education’s initiative Race to the Top, funded as part of the Education Recovery Act of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (AARA), will continue to view phonics instruction as an integral component and focus of reading instruction. Phonics, however, is not the cure-all for reading ills that some believe it to be. Rudolph Flesch’s book Why Johnny Can’t Read (1955), although it did bring the phonics debate to the attention of the public, typifies the kind of literature that takes a naive approach to a complex problem. As Heilman (1981) points out, “Flesch’s suggestions for teaching were quite primitive, consisting pri- marily of lists of words each presenting different letter-sound patterns. -

Fluency, Vocabulary and Comprehension Instruction

Fluency, Vocabulary and Comprehension Instruction Augustine Literacy Project - Charlotte Marion Idol, Site Coordinator Five Essential Components of Reading Instruction: 1.phonemic awareness 2.phonics 3.fluency 4.vocabulary 5.comprehension http://athome.readinghorizons.com/ Importance of Decoding skills: In many schools, 1st and 2nd grade instruction focuses on FVC instead of PA and P.(decoding) For our students, the holes in the foundation tend to be in PA and P. Please prioritize setting a firm foundation! For 1st month of tutoring, don’t worry about weaving in FVC instruction. Fluency/Vocabulary/Comprehension Instruction: What does it look like for 1st/2nd graders? How do I weave this instruction into each lesson? What are fun supplemental activities for “TAKE a BREAK” sessions? Fluency: ALP Manual: Tab 5, pp. 174-178 The ability to read text accurately and quickly. Scored as words read correctly per minute. ONLY DECODABLE TEXT! Easy independent reading level (95% success) Requires repeated ORAL reading practice with a partner providing modeling, feedback, and assistance Includes PROSODY: appropriate expression, inflection, pacing Activities to Promote Fluency Each session: You will already be doing repeated oral reading practice in lesson parts 3-5, 9 To add fun and prosody practice, when student rereads sentences in part 5, play “Roll Punctuation” or “Roll a Face.” Parts 3-5, 9. Handout B. Fluency “Take a Break” session activities: Paired Reading: Reading aloud along with your student to promote correct pacing, inflection, expression https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H5RJyUnAkWM Punctuation Punch: Periods, commas, question marks, exclamation point. Fun AVK stimulation! Use book Yo! Yes! to teach this technique. -

The End of Illiteracy?

The End of Illiteracy? The Holy Grail of Clackmannanshire TOM BURKARD CENTRE FOR POLICY STUDIES 57 Tufton Street London SW1P 3QL 1999 THE AUTHOR Tom Burkard is the Secretary of the Promethean Trust and has published several articles on how children learn to read. He contributed to the 1997 Daily Telegraph Schools Guide, and is a member of the NASUWT. His main academic interest is the interface between reading theory and classroom practice. His own remedial programme, recently featured in the Dyslexia Review, achieved outstanding results at Costessey High School in Norwich. His last Centre for Policy Study pamphlet, Reading Fever: Why phonics must come first (written with Martin Turner in 1996) proved instrumental in determining important issues in the National Curriculum for teacher training colleges. Acknowledgements Support towards research for this Study was given by the Institute for Policy Research. The Centre for Policy Studies never expresses a corporate view in any of its publications. Contributions are chosen for their independence of thought and cogency of argument. ISBN No. 1 897969 87 2 Centre for Policy Studies, March 1999 Printed by The Chameleon Press, 5 - 25 Burr Road, London SW18 CONTENTS Summary 1. Introduction 1 2. A brief history of the ‘reading wars’ 4 3. A comparison of analytic and synthetic phonics 9 4. Problems with the National Literacy Strategy 12 5. The success of synthetic phonics 17 6. Introducing synthetic phonics into the classroom 20 7. Recommendations 22 Appendix A: Problems with SATs 25 Appendix B: A summary of recent research on analytic phonics 27 Appendix C: Research on the effectiveness of synthetic phonics 32 SUMMARY The Government’s recognition of the gravity of the problem of illiteracy in Britain is welcome. -

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) in Plain Language

Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD) in Plain Language Academic Areas of Concern Students with specific learning disabilities (SLD) have severe trouble learning or demonstrating skills in one or more of these academic areas: oral expression reading fluency listening comprehension reading comprehension written expression mathematics calculation and basic reading skill mathematics problem solving Students with SLD often do well in some school subjects but have extreme difficulty with skills like decoding (sounding out) words, calculating math facts, or writing down their thoughts. Even with adequate instruction and intensive intervention, a student with SLD has low classroom achievement when compared to students without disabilities in the same grade. Specific information about how the student has responded to instruction and intensive intervention is used to decide if a student is SLD or if the student is not achieving for other reasons. Referral for Special Education When someone thinks a student might have any disability and needs special education, a referral for a special education evaluation is made to the school. The referral must be in writing and say why the person making the referral thinks the student has a disability. A group of people, called an IEP team, which includes the student’s parents, does an evaluation and decides if the student meets state and federal criteria. Three Criteria to Meet The three criteria (requirements) below must be considered by the IEP team and all 3 of them must be met in order to decide the student has SLD. 1. Inadequate Classroom Achievement - This means a student's academic skills in one or more academic areas of concern are well outside the expected range for students without disabilities of the same age. -

Some Issues in Phonics Instruction. Hempenstall, K

Some Issues in Phonics Instruction. Hempenstall, K. (No date). Some issues in phonics instruction. Education News 26/2/2001. [On-line]. Available: http://www.educationnews.org/some_issues_in_phonics_instructi.htm There are essentially two approaches to teaching phonics that influence what is taught: implicit and explicit phonics instruction. What is the difference? In an explicit (synthetic) program, students will learn the associations between the letters and their sounds. This may comprise showing students the graphemes and teaching them the sounds that correspond to them, as in “This letter you are looking at makes the sound sssss”. Alternatively, some teachers prefer teaching students single sounds first, and then later introducing the visual cue (the grapheme) for the sound, as in “You know the mmmm sound we’ve been practising, well here’s the letter used in writing that tells us to make that sound”. In an explicit program, the processes of blending (What word do these sounds make when we put them together mmm-aaa-nnn?”), and segmenting (“Sound out this word for me”) are also taught. It is of little value knowing what are the building blocks of our language’s structure if one does not know how to put those blocks together appropriately to allow written communication, or to separate them to enable decoding of a letter grouping. After letter-sound correspondence has been taught, phonograms (such as: er, ir, ur, wor, ear, sh, ee, th) are introduced, and more complex words can be introduced into reading activities. In conjunction with this approach "controlled vocabulary" stories may be used - books using only words decodable using the students' current knowledge base. -

Reading in the Twentieth Century. INSTITUTION Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, Ann Arbor, MI

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 479 530 CS 512 338 AUTHOR Pearson, P. David TITLE Reading in the Twentieth Century. INSTITUTION Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, Ann Arbor, MI. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2000-08-00 NOTE 46p.; CIERA Archive #01-08. CONTRACT R305R70004 AVAILABLE FROM CIERA/University of Michigan, 610 E. University Ave., 1600 SEB, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1259. Tel: 734-647-6940; Fax: 734- 763 -1229. For full text: http://www.ciera.org/library/archive/ 2001-08/0108pdp.pdf. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070). Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Educational History; *Educational Practices; Futures (of Society); Instructional Materials; *Reading Instruction; *Reading Processes; *Reading Research; Reading Skills; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Reading Theories ABSTRACT This paper discusses reading instruction in the 20th century. The paper begins with a tour of the historical pathways that have led people, at the century's end, to the "rocky and highly contested terrain educators currently occupy in reading pedagogy." After the author/educator unfolds his version of a map of that terrain in the paper, he speculates about pedagogical journeys that lie ahead in a new century and a new millennium. Although the focus is reading pedagogy, the paper seeks to connect the pedagogy to the broader scholarly ideas of each period. According to the paper, developments in reading pedagogy over the last century suggest that it is most useful to divide the century into thirds, roughly 1900-1935, 1935- 1970, and 1970-2000. The paper states that, as a guide in constructing a map of past and present, a legend is needed, a common set of criteria for examining ideas and practices in each period--several candidates suggest themselves, such as the dominant materials used by teachers in each period and the dominant pedagogical practices. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

The Effect of Teaching Phonics and Phonemic Awareness Training To

The Effect of Teaching Phonics and Phonemic Awareness Training to Adolescent Struggling Readers by Stephanie Hardesty Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Education December 2013 Goucher College Graduate Programs in Education Table of Contents List of Tables i Abstract ii I. Introduction 1 Statement of the Problem 2 Hypothesis 3 Operational Definitions 3 II. Literature Review 6 Phonemic Awareness Training and Phonics 6 Reading Instruction in the High School Setting 7 Reading Remediation 10 Summary 13 III. Methods 14 Participants 14 Instrument 15 Procedure 16 IV. Results 19 V. Discussion 20 Implications 20 Threats to Validity 21 Comparison to Previous Studies 22 Suggestions for Future Research 24 References 25 List of Tables 1. Pre- and Post-SRI Test Results 19 i Abstract The purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy of teaching phonics and phonemic awareness training to adolescent struggling readers. The measurement tool was the Scholastic Reading Inventory (SRI). This study involved the use of a pretest/posttest design to compare data prior to the implementation of the reading intervention, System 44, to data after the intervention was complete (one to two years). Achievement gains were not significant, though results could be attributable to a number of intervening factors. Research in the area of high school reading remediation should continue given the continued disagreement over best practices and the new standards that must be met per the Common Core. ii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Advanced or proficient reading abilities are one of the primary yet essential skills that should be mastered by every student. -

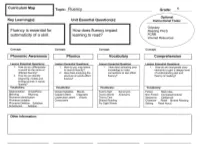

Vocabulary Key Learning(S): Topic: Fluency Unit Essential Question(S

Topic: Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools: Odyssey Fluency is essential for How does fluency impact Reading PALS automaticity of a skill. learning to read? FCRR Internet Resources Concept: Concept: Concept: Concept: Awareness Phonics Vocabulary Comprehension Phonemic I Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Questions: Lesson Essential Question Lesson Essential Questions: 1. How do you differentiate 1. How do you map letters 1. How does activating prior 1. How do we incorporate story a sound as the same or to sounds fluently? knowledge to make elements to gain a deeper level different fluently? 2. How does analyzing the connections to text affect of understanding text and 2. How do you identify structure of words affect fluency? fluency of reading? beginning, middle and fluency? ending sounds in words fluently? Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Vocabulary: Segmentation Onset/Rime Closed Syllables Blends Text to Self Synonyms Fiction Main Idea Blending Rhyming Capital Letters Diagraphs Text to World Antonyms Non-Fiction Compare/Contrast Phoneme Identification Lowercase Letters Vowels Text to Text Sequence Categorize Phoneme Isolation Consonants Shared Reading Character Retell Shared Reading Phoneme Deletion Syllables Fry Sight Words Setting Read Aloud Substitution Addition Other Information: Concert: Concept: Concept: Concept: I Writing L Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions Lesson Essential Questions 1. How do you transfer sounds to symbols, words, and express meaning in writing fluently? Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Vocabulary Fry Sight Words Capital Letters Lowercase Letters Topic: Introduction to Reading Fluency Grade: K Optional Key Learning(s): Unit Essential Question(s): Instructional Tools -Sound Wall Developing fluent skills leads to How do I become a fluent reader? -Alphabet Cards -Sight Words comprehension. -

The Relationship Between Fluency and Comprehension

The Relationship between Fluency and Comprehension By Tania Myers Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Education July 2015 Graduate Programs in Education Goucher College Table of Contents List of Tables i Abstract ii I. Introduction 1 Statement of Problem 2 Hypothesis 2 Operational Definitions 2 II. Review of the Literature 4 Defining Fluency and Comprehension 5 Relationship between Fluency and Comprehension 8 Boosting Reading Fluency and Comprehension in the Classroom 9 Progress Monitoring Fluency and Comprehension 14 Summary 18 III. Methods 19 Design 19 Participants 19 Instruments 20 Procedure 20 IV. Results 22 V. Discussion 24 Implications of Results 25 Threats to Validity and Reliability 26 Connections to Previous Studies 28 Recommendations for Future Research 29 References 32 List of Tables 1. Means and Standard Deviations of DIBELS Oral Reading Fluency and MAP Reading 22 Scores 2. Pearson Correlation between DIBELS Oral Reading Fluency and MAP Reading 22 Scores During Each Test Interval (Fall, Winter, and Spring) i Abstract The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between reading fluency and comprehension and whether a student’s fluency rate impacted his or her ability to comprehend information. The study looked closely at the performance of 23 students enrolled in a second grade class. The measurement tools used were the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, Sixth Edition (DIBELS), Oral Reading Fluency Assessment, and the Measures of Academic Progress Reading Assessment. The study involved the use of data collected during fall, spring, and winter testing intervals from the 2014-2015 school year.