The Concurrent Operation of Federal and Provincial Laws in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Option Laws in Ontario Sacred Boundaries: Local Opi'ion Laws in Ontario

SACRED BOUNDARIES: LOCAL OPTION LAWS IN ONTARIO SACRED BOUNDARIES: LOCAL OPI'ION LAWS IN ONTARIO By. KATHY LENORE BROCK, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University September 1982 MASTER OF ARTS (1982) MCMASTER UNIVERSITY (Political Science) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Sacred Boundaries: Local Option Laws in Ontario AUTHOR: Kathy Lenore Brock, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor T.J. Lewis NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 162 ii Abstract The laws of Ontario operate on the principle that indivi duals should govern their own conduct unless it affects others adversely. The laws are created to protect individuals and their property and to ensure that citizens respect the rights of others. However, laws are protected and entrenched which defy this principle by permitting and fostering intolerance. This thesis addresses the local option laws of Ontario's liquor legislation which protect and legitimize invasion of personal liberty. These laws permit municipalities to prohi bit or restrict retail sale of liquor within their boundaries by vote or by COQ~cil decision. Local option has persisted t:b.roughout Ontario's history and is unlikely to be abolished despite the growing acceptance of liquor in society. To explain the longevity of these la.... ·ts, J.R. Gusfield' s approach to understanding moral crusades is used. Local option laws have become symbols of the status and influence of the so ber, industrious middleclass of the 1800's who founded Ontario. The right to control drinking reassures people vlho adhere to the traditional values that their views are respected in society. -

591 Charters of Incorporation.—The Number of Companies Incor

HOMESTEAD ENTRIES 591 9.—Receipts of Patents and Homestead Entries in the fiscal years 1914-1918. Sources of Receipts. "1914. 1915. 1916. 1917. 1918. $ $ $ $ Homestead fees 317,412 238,295 170,350 112,110 83,180 Cash sales 1,279,224 691,123 1,073,970 2,707,204 3,046,092 Scrip sales 240 80 333 131 Timber dues 378,365 310,934 378,961 429,403 482,006 Hay permits, mining, stone quarries, etc., cash 889,863 1,600,455 493,281 600,934 630,473 All other receipts 448,716 335,964 327,078 340,254 315,928 Gross revenue 3,313,820 3,176,851 2,443,640 4,190,238 4,557,810 Refunds 277,309 317,765 143,943 134,243 113,680 Net revenue 3,036,511 2,859,086 2,299,697 4,055,995 4,444,130 Total revenue, 1872-1918 45,619,673 48,478,759 50,778,457 54,834,452 59,278,582 Letters patent for Dominion lands NO 31,053 24,260 18,989 18,774 23,227 Homestead entries " 31,829 24,088 17,030 11,199 8,319 DEPARTMENT OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE. Charters of Incorporation.—The number of companies incor porated under The Companies Act during the fiscal year 1917-18 was 574, with a total capitalization of $335,982,400, and the number of existing companies to which supplementary letters patent were issued was 77, of which 41 increased their capital stock by $69,321,400 and 4 decreased their capital stock by $1,884,300. -

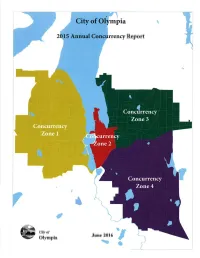

Annual Concurrency Report

pra Report Ciry of June 2016 Olympia I TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 .2 A. Actual Traffic Growth and Six Year Forecast .J B. Level of Service (LOS) Analysis .8 Conclusions .......9 A. Conformance with Adopted LOS Standards 9 B. Marginal Projects.... .....10 C. Level of Service on State Facilities .....1 I Summary .... ....1 1 Appendix A: Maps of Traffic Growth in the Four Concurrency Analysis Zones..... 1 Appendix B: Intersection Level of Service Analysis vs. Project Needs .. Appendix C: Unsignalized Intersection Warrant Analysis ................. vll Appendix D: Link Level of Service Analysis .....................xi Olympia 2OtS Concurrency Report INTRODUCTION ln 1995, the City of Olympia (City), in compliance with the Growth Management Act's (GMA) internal consistency requirement, adopted the Transportation Concurrency Ordinance (No. 55aO). One objective of GMA's internal consistency requirement is to maintain concurrency between a jurisdiction's infrastructure investments and growth. Following this objective, the City's Ordinance prohibits development approval if the development causes the Level of Service (LOS) on a transportation facility to declíne below the standards adopted in the transportation element of the Olympia's Comprehensive Plon (Comp Plan). The ordinance contains two features, as follows: a Development is not allowed unless (or until) transportation improvements or strategies to provide for the impacts of the development are in place at the time of development or withín six years of the time the project comes on line. a Annual review of the concurrency management system is required along with the annual review and update of the Copital Facilíties Plon (CFP) and transportation element of the Comp Plan. -

Paramountcy in Penal Legislation

OCCUPYING THE FIELD : PARAMOUNTCY IN PENAL LEGISLATION BORA LASKIN* Toronto Among the time-honoured doctrines of Canadian constitutional law none has a more disarming simplicity and none is more ques- tion-begging than the last of the four propositions proclaimed by Lord Tomlin in the Fish Canneries case' and repeated on three subsequent occasions by the Privy Council.2 It reads as follows : "There can be a domain in which Provincial and Dominion legisla- tion may overlap, in which case neither legislation will be ultra vires if the field is clear, but if the field is not clear and the two legislations meet the Dominion legislation must prevail."' The issues raised by this pronouncement are concomitants of federal- ism, familiar in the United States and in Australia, and immanent in the constitutions of the new federal states that have come into being since the end of World War Two.4 Three fairly recent decisions of the Supreme Court of Canada, in each of which there were dissents, illustrate that court's ap- preciation ofthose issues as they emerged in provincial and federal penal legislation. The three cases are sufficiently different from one another in their facts and supporting legislation to provide adequate perspective for an examination of the doctrine of the "occupied field"-the paramountcy doctrine, to use an equivalent-as it pertains to penal enactments. *Bora Laskin, Q.C., of the Faculty of Law, University of Toronto. 1 A.-G. for Canada v. A.-G . for British Columbia, [1930] A.C. 111, [19301 1 D.L.R. 194, [192913 W.W.R. -

Product Liability Defense: Preemption in Canada

Product Liability Defence North and South of the Border: Is there such thing as Canadian pre-emption? By Craig Lockwood, Sonia Bjorkquist and Alexis Beale from Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP and Maura Kathleen Monaghan, Jacob W. Stahl and Christel Y. Tham from Debevoise & Plimpton LLP PRODUCT LIABILITY DEFENCE NORTH AND SOUTH OF THE BORDER Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt llp | Debevoise & Plimpton Table of Contents Introduction 3 An Overview of the U.S. Experience 5 The Canadian Experience 9 Recent Developments 15 Conclusion 19 2 PRODUCT LIABILITY DEFENCE NORTH AND SOUTH OF THE BORDER Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt llp | Debevoise & Plimpton 1 Introduction In Canada, most food products, pharmaceuticals, cosmetic products and medical devices are subject to federal regulation pursuant to the Food and Drugs Act (FDA) and other related legislation.1 Similar to the U.S. regulatory scheme, the Canadian regime is administered and enforced by the federal regulatory authorities – most notably Health Canada – responsible for establishing standards of safety for, and regulating and approving the use of, health-related products sold in Canada. However, U.S. manufacturers who sell regulated products in Canada may be surprised to learn that compliance with the FDA and associated regulatory frameworks has not historically served as a defence to product liability claims. In particular, the Canadian regulatory regime has traditionally operated as a ‘regulatory floor,’ rather than a comprehensive code of conduct. Conversely, applicable regulatory frameworks in the United States may prescribe comprehensive codes of conduct that do not leave the regulated entity with any discretion, potentially creating irreconcilable conflicts between the state and federal governments. -

Transportation Concurrency Requirements Level of Service

Assistance Bulletin Transportation Concurrency Snohomish County #59 Planning and Development Services Requirements Updated April 2016 WWW.SNOCO.ORG Keyword: Assistance Bulletins Concurrency Visit us at : 2nd Floor Robert J. Drewel Bldg. Q: What is Chapter 30.66B SCC? 3000 Rockefeller Avenue Everett, WA 98201 A: Chapter 30.66B SCC is the chapter in Title 30 SCC, the County’s Unified Develop- 425-388-3311 ment Code (UDC), that contains the Concurrency and Road Impact Mitigation require- 1-800-562-4367, ext. 3311 ments relating to new development. Chapter 30.66B SCC includes requirements for con- currency to comply with the Washington State Growth Management Act (GMA) and re- quires developers to mitigate the traffic impacts on the County’s arterial road network from new development. Q: What is the concurrency management system? A: The Snohomish County concurrency management system provides the basis for moni- toring the traffic impacts of land development, and helps determine if transportation im- provements are keeping pace with the prevailing rate of land development. In order for a development to be granted approval it must obtain a concurrency determination. Q: What is a “ concurrency determination” ? A: Each development application is reviewed to determine whether or not there is enough PERMIT SUBMITTAL capacity on the County’s arterial road network in the vicinity of the development to ac- Appointment commodate the new traffic that will be generated by the development, without having traf- 425.388.3311 fic congestion increase to levels beyond that allowed in Chapter 30.66B SCC. Simply Ext. 2790 stated, if there is sufficient arterial capacity, the development is deemed concurrent and can proceed. -

Current Trends in Canadian Federalism. Centripetal and Centrifugal Forces in Canadian Division of Powers ERIKA ARBAN1 Summary

Current trends in Canadian federalism. Centripetal and centrifugal forces in Canadian division of powers ERIKA ARBAN1 Summary: 1.Introduction; 2. Canadian Federalism and the division of legislative powers; 3. Judicial interpretation of the division of powers; 4. Level of (de)centralization of Canadian federalism; 5. Future changes in the division of powers; 6. Conclusions. 1. Introduction Canadian federalism is often described as the most decentralized in the world. This paper tries to identify elements of Canadian federalism which support and which go against this statement, to ultimately determine whether Canadian federalism is presently on a decentralizing (centrifugal) or centralizing (centripetal) course. As pointed out by Ronald Watts, in determining the level of (de)centralization of a given federal scheme, the first task becomes that of clarifying which powers we want to analyze. 1 L.L.M., University of Arizona; Ph.D. Candidate, University of Ottawa. 1 Centralization or decentralization can refer both to the legislative powers assigned to each level of government (federal or provincial in Canada), or to the role played by the various components in federal decision making.2 Also, we can analyze the level of (de)centralization by looking at the administrative bodies in a federal state and how federal institutions are more or less present locally. In this paper, however, I will focus only on the level of (de)centralization in the distribution of legislatives powers between federal Parliament and provincial legislatures in Canada as stemming from the Canadian Constitution and as shaped by the decisions of the Privy Council (hereinafter, “P.C.”) and the Supreme Court of Canada (hereinafter, “SCC”). -

Untangling the Web of Canadian Privacy Laws

Reproduced by permission of Thomson Reuters Canada Limited from Annual Review of Civil Litigation 2020, ed. The Honourable Mr. Justice Todd L. Archibald. Shining a Light on Privacy: Untangling the Web of Canadian Privacy Laws BONNIE FISH AND ALEXANDER EVANGELISTA1 It was terribly dangerous to let your thoughts wander when you were in any public place or within range of a telescreen. The smallest thing could give you away. George Orwell, 1984 I. THE GENESIS OF PRIVACY LITIGATION Although there are more Canadian privacy laws than ever before and the right to privacy has quasi-constitutional status,2 Canadian citizens have never had greater cause for concern about their privacy. Our devices make public a dizzying amount of our personal information.3 We share information about our preferences and location with retailers and data brokers when shopping for online products and when shopping in physical stores using our credit cards, payment cards or apps. Smart homes and smart cities make possible Orwellian surveillance and data capture that previously would have been illegal without a judicial warrant.4 The illusion of anonymous or secure internet activity has been shattered5 by large scale privacy breaches that have exposed the vulnerability of our personal information to hackers.6 The COVID-19 crisis raises new privacy concerns as governments and private institutions exert extraordinary powers to control the outbreak, including the use of surveillance technologies.7 1 Bonnie Fish is a Partner and the Director of Legal Research at Fogler, Rubinoff LLP, Alexander Evangelista is an associate in the litigation department of Fogler, Rubinoff LLP. -

Sr 826/Palmetto Expressway Project Development & Environment Study from Sr 93/I‐75 to Golden Glades Interchange

METHODOLOGY LETTER OF UNDERSTANDING SR 826/PALMETTO EXPRESSWAY PROJECT DEVELOPMENT & ENVIRONMENT STUDY FROM SR 93/I‐75 TO GOLDEN GLADES INTERCHANGE SYSTEMS INTERCHANGE MODIFICATION REPORT (SIMR) Financial Project ID: 418423‐1‐22‐01 FAP No.: 4751 146 P / ETDM No.: 11241 Miami‐Dade County Prepared For: FDOT District Six 1000 NW 111th Avenue Miami, Florida 33172 Prepared by: Reynolds, Smith and Hills, Inc. 6161 Blue Lagoon Drive, Suite 200 Miami, Florida 33126 March 9, 2012 SR 826/Palmetto Expressway PD&E Study METHODOLOGY LETTER OF UNDERSTANDING MEMORANDUM DATE: March 9, 2012 TO: Phil Steinmiller, AICP Florida Department of Transportation District Six Interchange Review Committee Chair FROM: Dat Huynh, PE FDOT, District Six Project Manager SUBJECT: Methodology Letter of Understanding (MLOU) SR 826/Palmetto Expressway PD&E Study Systems Interchange Modification Report (SIMR) FDOT, District Six FM No.: 418423‐1‐22‐01 Dear Interchange Coordinator: This document serves as the Methodology Letter of Understanding (MLOU) between the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) Systems Planning Office, Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise (Cooperating Approval Authority) and FDOT District Six Interchange Review Committee (Applicant) regarding the preparation of a Systems Interchange Modification Report (SIMR) for a portion of SR 826/Palmetto Expressway located in Miami‐Dade County, Florida. The SIMR relates to the proposed improvements for the segment of SR 826 between I‐75 and the Golden Glades Interchange (GGI). The project proposes to widen SR 826 mainline from I‐75 to Golden Glades Interchange to provide additional lanes that could serve as general use lanes or special use lanes (managed lanes). -

A Brief History of the Temperance Movement in London and the Surrounding Area

Western University Scholarship@Western Psychology Publications Psychology Department 2014 A Brief History of the Temperance Movement in London and the Surrounding Area Marvin L. Simner Western University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/psychologypub Part of the Canadian History Commons Citation of this paper: Simner, Marvin L., "A Brief History of the Temperance Movement in London and the Surrounding Area" (2014). Psychology Publications. 118. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/psychologypub/118 The London and Middlesex Historian Volume 23, Autumn 2014 A Brief History of the Temperance Movement in London and the Surrounding Area Marvin L. Simner The Need for Temperance t one time in the mid-to-late 1800s, there were as many as 11 temp- Organizations A In the early 1830s, London, with a erance lodges in London, Ontario along with a local chapter of the Woman's Christian population of around 1,300, already had Temperance Union (WCTU). The majority seven taverns. By 1864, and now with a population of around 14,000, the number of of the lodges, which typically met on a 1 weekly basis, represented three of the major licenced taverns had grown to 58. Then, in national temperance organizations in North the year of Confederation, the London Board America: Sons of Temperance, Independent of Police issued four more licences which meant that by 1867 there was one tavern for Order of Good Templars, and the British 2 American Order of Good Templars which every 225 citizens. was founded here in London. The aim of Since many of these establishments this report is to outline the nature and were clustered in the downtown area around accomplishments of these lodges and their King Street, this street soon became known national affiliates along with the WCTU. -

225 Watertight Compartments: Getting Back to the Constitutional Division of Powers I. Introduction

GETTING BACK TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL DIVISION OF POWERS 225 WATERTIGHT COMPARTMENTS: GETTING BACK TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL DIVISION OF POWERS ASHER HONICKMAN* This article offers a fresh examination of the constitutional division of powers. The author argues that sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 establish exclusive jurisdictional spheres — what the Privy Council once termed “watertight compartments.” This mutual exclusivity is emphasized and reinforced throughout these sections and leaves very little room for legitimate overlap. While some degree of overlap is permissible under this scheme — particularly incidental effects, genuine double aspects, and limited ancillary powers — overlap must be constrained in a principled fashion to comply with the exclusivity principle. The modern trend toward flexibility and freer overlap is contrary to the constitutional text. The author argues that while some deviation from the text is inevitable due to the presumption of constitutionality and stare decisis, the Supreme Court should return to a more exclusivist footing in accordance with the text. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 226 II. THE EXCLUSIVITY PRINCIPLE .................................. 227 A. FROM QUEBEC TO THE BRITISH PARLIAMENT ................. 227 B. THE NON OBSTANTE CLAUSE AND THE DEEMING PROVISION ...... 231 C. CONCURRENT POWERS ................................... 234 III. PITH AND SUBSTANCE AND LEGITIMATE OVERLAP ................. 235 A. INTERJURISDICTIONAL IMMUNITY ......................... -

Insights from Canada for American Constitutional Federalism Stephen F

Penn State Law eLibrary Journal Articles Faculty Works 2014 Insights from Canada for American Constitutional Federalism Stephen F. Ross Penn State Law Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/fac_works Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Stephen F. Ross, Insights from Canada for American Constitutional Federalism, 16 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 891 (2014). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES INSIGHTS FROM CANADA FOR AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONAL FEDERALISM Stephen F Ross* INTRODUCTION National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius' has again fo- cused widespread public attention on the role of the United States Supreme Court as an active arbiter of the balance of power between the federal government and the states. This has been an important and controversial topic throughout American as well as Canadian constitutional history, raising related questions of constitutional the- ory for a federalist republic: Whatjustifies unelected judges interfer- ing with the ordinary political process with regard to federalism ques- tions? Can courts create judicially manageable doctrines to police federalism, with anything more than the raw policy preferences of five justices as to whether a particular legislative issue is