GMA Concurrency Goal and the State Transportation System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

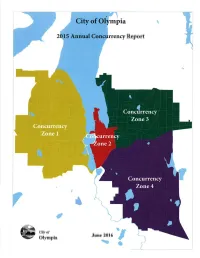

Annual Concurrency Report

pra Report Ciry of June 2016 Olympia I TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 .2 A. Actual Traffic Growth and Six Year Forecast .J B. Level of Service (LOS) Analysis .8 Conclusions .......9 A. Conformance with Adopted LOS Standards 9 B. Marginal Projects.... .....10 C. Level of Service on State Facilities .....1 I Summary .... ....1 1 Appendix A: Maps of Traffic Growth in the Four Concurrency Analysis Zones..... 1 Appendix B: Intersection Level of Service Analysis vs. Project Needs .. Appendix C: Unsignalized Intersection Warrant Analysis ................. vll Appendix D: Link Level of Service Analysis .....................xi Olympia 2OtS Concurrency Report INTRODUCTION ln 1995, the City of Olympia (City), in compliance with the Growth Management Act's (GMA) internal consistency requirement, adopted the Transportation Concurrency Ordinance (No. 55aO). One objective of GMA's internal consistency requirement is to maintain concurrency between a jurisdiction's infrastructure investments and growth. Following this objective, the City's Ordinance prohibits development approval if the development causes the Level of Service (LOS) on a transportation facility to declíne below the standards adopted in the transportation element of the Olympia's Comprehensive Plon (Comp Plan). The ordinance contains two features, as follows: a Development is not allowed unless (or until) transportation improvements or strategies to provide for the impacts of the development are in place at the time of development or withín six years of the time the project comes on line. a Annual review of the concurrency management system is required along with the annual review and update of the Copital Facilíties Plon (CFP) and transportation element of the Comp Plan. -

Transportation Concurrency Requirements Level of Service

Assistance Bulletin Transportation Concurrency Snohomish County #59 Planning and Development Services Requirements Updated April 2016 WWW.SNOCO.ORG Keyword: Assistance Bulletins Concurrency Visit us at : 2nd Floor Robert J. Drewel Bldg. Q: What is Chapter 30.66B SCC? 3000 Rockefeller Avenue Everett, WA 98201 A: Chapter 30.66B SCC is the chapter in Title 30 SCC, the County’s Unified Develop- 425-388-3311 ment Code (UDC), that contains the Concurrency and Road Impact Mitigation require- 1-800-562-4367, ext. 3311 ments relating to new development. Chapter 30.66B SCC includes requirements for con- currency to comply with the Washington State Growth Management Act (GMA) and re- quires developers to mitigate the traffic impacts on the County’s arterial road network from new development. Q: What is the concurrency management system? A: The Snohomish County concurrency management system provides the basis for moni- toring the traffic impacts of land development, and helps determine if transportation im- provements are keeping pace with the prevailing rate of land development. In order for a development to be granted approval it must obtain a concurrency determination. Q: What is a “ concurrency determination” ? A: Each development application is reviewed to determine whether or not there is enough PERMIT SUBMITTAL capacity on the County’s arterial road network in the vicinity of the development to ac- Appointment commodate the new traffic that will be generated by the development, without having traf- 425.388.3311 fic congestion increase to levels beyond that allowed in Chapter 30.66B SCC. Simply Ext. 2790 stated, if there is sufficient arterial capacity, the development is deemed concurrent and can proceed. -

Sr 826/Palmetto Expressway Project Development & Environment Study from Sr 93/I‐75 to Golden Glades Interchange

METHODOLOGY LETTER OF UNDERSTANDING SR 826/PALMETTO EXPRESSWAY PROJECT DEVELOPMENT & ENVIRONMENT STUDY FROM SR 93/I‐75 TO GOLDEN GLADES INTERCHANGE SYSTEMS INTERCHANGE MODIFICATION REPORT (SIMR) Financial Project ID: 418423‐1‐22‐01 FAP No.: 4751 146 P / ETDM No.: 11241 Miami‐Dade County Prepared For: FDOT District Six 1000 NW 111th Avenue Miami, Florida 33172 Prepared by: Reynolds, Smith and Hills, Inc. 6161 Blue Lagoon Drive, Suite 200 Miami, Florida 33126 March 9, 2012 SR 826/Palmetto Expressway PD&E Study METHODOLOGY LETTER OF UNDERSTANDING MEMORANDUM DATE: March 9, 2012 TO: Phil Steinmiller, AICP Florida Department of Transportation District Six Interchange Review Committee Chair FROM: Dat Huynh, PE FDOT, District Six Project Manager SUBJECT: Methodology Letter of Understanding (MLOU) SR 826/Palmetto Expressway PD&E Study Systems Interchange Modification Report (SIMR) FDOT, District Six FM No.: 418423‐1‐22‐01 Dear Interchange Coordinator: This document serves as the Methodology Letter of Understanding (MLOU) between the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) Systems Planning Office, Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise (Cooperating Approval Authority) and FDOT District Six Interchange Review Committee (Applicant) regarding the preparation of a Systems Interchange Modification Report (SIMR) for a portion of SR 826/Palmetto Expressway located in Miami‐Dade County, Florida. The SIMR relates to the proposed improvements for the segment of SR 826 between I‐75 and the Golden Glades Interchange (GGI). The project proposes to widen SR 826 mainline from I‐75 to Golden Glades Interchange to provide additional lanes that could serve as general use lanes or special use lanes (managed lanes). -

A83c9c5f-7Ef0-4B18-A0df-60674Ef940e5

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................................. 2 PROPOSED LAND DEVELOPMENT PLAN ................................................................................................................................... 2 STUDY AREA ................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 EXISTING PM PEAK HOUR TRAFFIC VOLUME CONDITIONS .................................................................................................... 2 ESTIMATE OF SITE GENERATED TRAFFIC ................................................................................................................................. 3 PROJECT TRIP DISTRIBUTION AND ASSIGNMENT ................................................................................................................... 5 ROADWAY SEGMENT ANALYSIS ................................................................................................................................................. 7 CONCLUSION .................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 LIST OF TABLES TABLE 1 - TRANSPORTATION CONCURRENCY ROADWAY NETWORK SEGMENTS ..................................................................................... -

Transportation Concurrency Review

Transportation Concurrency Review December 30, 2019 TO: Eric Shjarback, PE City Engineer Anacortes Public Works Engineering FROM: Andrew Bratlien, PE SUBJECT: Anacortes 2019 Citywide LOS Summary INTRODUCTION This memorandum describes the method and assumptions of the 2019 Anacortes transportation concurrency model development process. It summarizes the results of the 2019 and 2025 transportation Level of Service analysis and identifies transportation improvement project recommendations. CONCURRENCY MANAGEMENT BACKGROUND Concurrency is mandated under the 1990 Growth Management Act (GMA) passed by the Washington State legislature to address and mitigate problems associated with growth. The GMA requires that transportation improvements or strategies necessary to accommodate development must be made concurrently with land development. Concurrency requires transportation improvements to be either (a) in place at the time of development or (b) that a financial commitment is in place to complete the improvements within six years of development (RCW 36.70A.070(6)(b)). Transportation concurrency requires that the transportation impacts of land use development actions do not reduce transportation Level of Service (LOS) below the responsible agency’s adopted LOS standards. If it is determined during the development review process that the proposed land use action would reduce LOS below the adopted standard, the development must be modified to reduce its transportation impact or provide corrective transportation improvements. Transportation improvements, which may include project funding, must be identified and programmed within a six-year period from development permitting. Should any of these requirements fail to be met, the development proposal cannot be granted approval. EXISTING CONDITIONS Travel Demand Model Recalibration The Anacortes travel demand model represents the most current planning-level traffic forecasting tool for the City of Anacortes. -

Transportation Concurrency

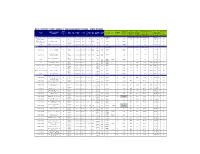

BAY COUNTY CONCURRENCY MANAGEMENT SYSTEM - STATE ROADS 1% of 5% of Road # AVAILABLE 110% Maximum Trips De minimus STATE ROAD AND FUNC NO. FACILITY SEG. SIG/ LOS (STD) COUNT CURRENT capacity at capacity at New New ROAD Segment LOS AREA OF 2014 AADT AVG CAPACITY Volume at Added impact CLASS LNS TYPE LTH MILE MAX VOL STA # LOS (project trips not adopted adopted AADT LOS SEGMENT SIG Adopted LOS to AADT allowed ID included) LOS AADT LOS AADT SR 20 Washington Co. Line to SR Principal ( C ) SR 20 (Segment is on the 71 2 Undivided Trans. 1 7.88 0.127 249 3,000 B 11,100 155 776 15,510 3,000 B Yes Intrastate System) 77 Arterial 14,100 Principal ( C ) SR 20 (Segment is on the SR 77 to US 231 72 2 Undivided Trans. 1 15.7 0.064 192T 1,754 B 12,346 155 776 15,510 39 1,793 B Yes Intrastate System) Arterial 14,100 Principal (C) SR 20 US 231 to Calhoun Co. Line 73 2 Undivided Trans. 0 2.45 0 1 3,800 B 10,300 155 776 15,510 3,800 B Yes Arterial 14,100 SR 22 (D) Urban SR 22 - 3rd St East Ave to Bus 98 74 2 Undivided Urbanized 1 0.48 2.083 1602 3,200 C 12,000 167 836 16,720 3,200 C Yes Collector 15,200 (D) Bus 98 to Transmitter Minor SR 22 - 3rd St 75 2 Undivided Urbanized 1 0.56 1.786 5016 11,000 C 5,500 182 908 18,150 11,000 C Yes Road/CR 2327 Arterial 16,500 (D) Transmitter Rd to Tyndall Minor SR 22 76 2 Undivided Urbanized 2 1 2.0 5192 9,600 10,600 D 15,200 167 836 16,720 10,600 D Yes Pkwy Arterial 15,200 1601 11,600 Minor (D) 5189 14,000 SR 22 Tyndall Pkwy to Star Ave 77 2 Undivided Urbanized 2 1.51 1.32 15,250 C 1,250 182 908 18,150 2,099 17,349 F Yes Arterial 16,500 5195 16,500 Minor (D) SR 22 (used by Co.) Star Ave to CR 2297 78 2 Undivided Urbanized 0 4.06 0 1625 6,800 B 9,700 182 908 18,150 3,115 9,915 C Yes Arterial 16,500 Minor (D) SR 22 (used by Co.) CR 2297 to UB 79 2 Undivided Urbanized 0 0.52 0 260 4,000 B 12,500 182 908 18,150 461 4,461 B Yes Arterial 16,500 Minor (C) SR 22 (used in State CMS) Star Ave to UB 80 2 Undivided Trans. -

Bay County Concurrency Management System - County Roads

BAY COUNTY CONCURRENCY MANAGEMENT SYSTEM - COUNTY ROADS AVAILABLE 1% of capacity 5% of capacity 110% Maximum Trips De minimus COUNTY/CITY ROAD Road NO. FACILITY # OF SEG. SIG/ LOS (STD) COUNT CURRENT New FUNC CLASS LOS AREA 2018 AADT AVG CAPACITY at adopted at adopted LOS Volume at Added to New AADT impact ROAD AND SEGMENT Segment ID LNS TYPE SIG LTH MILE MAX VOL STA # LOS (project trips not LOS LOS AADT AADT Adopted LOS AADT allowed included) CR 28 (11th Street) (D) 5048 5,900 Urban CR 28 (11th Street) Beck Ave to Lisenby Ave 1 2 Undivided 2 1.05 1.90 Urbanized 14,850 5049 6,100 B 8,750 163 817 16,335 6,100 B Yes Collector 5050 6,300 Urban (D) CR 28 (11th Street) Lisenby Ave to Harrison Ave 2 2 Undivided 3 1.43 2.10 Urbanized 5051 11,000 D 2,680 150 752 15,048 11,000 D Yes Collector 13,680 Urban (D) CR 28 (11th Street) Harrison Ave to SR77 3 2 Undivided 1 0.61 1.64 Urbanized 5055 11,500 C 3,350 163 817 16,335 11,500 C Yes Collector 14,850 Urban (D) CR 28 (11th Street) SR77 to East Ave 4 2 Undivided 3 1.5 2.00 Urbanized 5091 10,500 D 3,180 150 752 15,048 10,500 D Yes Collector 13,680 Urban (D) CR 28 (11th Street) East Ave to Transmitter Rd 5 2 Undivided 2 1.05 1.90 Urbanized 5172 6,900 B 7,950 163 817 16,335 6,900 B Yes Collector 14,850 Transmitter Rd to US98 Urban (D) CR 28 (11th Street) 6 2 Undivided 0 1 0.00 Urbanized 5213 2,100 B 12,750 163 817 16,335 2,100 B Yes (Tyndall Pkwy) Collector 14,850 CR 385 (Frankford Ave) Urban (D) CR 385 Frankford Ave Bus98 to US98 7 2 Undivided 2 0.7 2.86 Urbanized 5046 9,100 C 4,580 150 752 15,048 9,100 C Yes Collector 13,680 Urban (D) CR 385 Frankford Ave US98 to 23rd St. -

Skagit County Jail Facility Transportation Concurrency Review 1. Project Description

SKAGIT COUNTY JAIL FACILITY TRANSPORTATION CONCURRENCY REVIEW David Evans and Associates, Inc. (DEA) has completed this concurrency analysis in accordance with the City of Mount Vernon Municipal Code (MVMC) Chapter 14.10 – Concurrency Management. The City of Mount Vernon (City) has adopted a comprehensive development review process that integrates a concurrency review and the traditional site development Traffic Impact Analysis (TIA). This concurrency review was performed for two potential locations for the Skagit County Jail within the City limits: the Alf Christianson Seed Site and the Truck City/Suzanne Lane Site. 1. PROJECT DESCRIPTION Skagit County is considering two alternative locations to construct a new 400-.ed /ail facility, which can .e e0panda.le to 100 .eds total in 20 to 30 years, within the City limits: the Alf Christianson Seed Site and the Truck City/Suzanne ,ane Site. The two alternative sites are shown in Figure 1 and are descri.ed as follows: • Alf Christianson Seed Site: This pro/ect site is located on the southwest 4uadrant of the intersection of E 5incaid Street / the I-3 south.ound (S6) off- and on-ramp. It is .ounded .y E 5incaid Street to the north, the railroad tracks to the west, 7nion Street to the south, and the I-3 S6 on-ramp to the east. The e0isting site is comprised primarily of industrial warehouse .uildings surrounded .y vacant or previously cleared lots. The warehouse .uildings will .e demolished. Access to the new /ail facility was tested .oth from E 5incaid Street to the north and from S 8th Street/7nion Street to the south. -

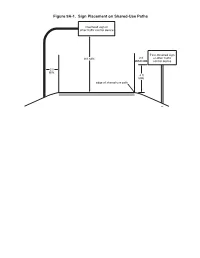

Figure 9A-1. Sign Placement on Shared-Use Paths

Figure 9A-1. Sign Placement on Shared-Use Paths Overhead sign or other traffic control device Post-mounted sign 8 ft MIN. 2 ft or other traffic MIN. control device 2 ft MIN. 4 ft MIN. edge of shared-use path Figure 9B-1. Regulatory Signs and Plaques for Bicycle Facilities (Sheet 1 of 2) R3-17aP R1-1 R1-2 R3-5hP R3-7bP R3-17 R3-17bP R4-1 R4-2 R4-3 R4-4 R4-7 R4-16 R5-1b R9-3cP R4-19 R5-3 R5-6 R5-10dP R7-9 R7-9a R9-3 R9-5 R9-6 R9-7 R9-13 R9-14 R9-15 R9-20 R9-21 R9-22 R9-23 R9-23a R9-23b R10-4 R10-12b R10-22 R10-24 R10-25 R10-26 R10-40 R10-40a R10-41 R10-41a R10-41b Figure 9B-1. Regulatory Signs and Plaques for Bicycle Facilities (Sheet 2 of 2) R15-2P R15-1 R15-8 Figure 9B-2. Example of Applications of the Except Bicycles Regulatory Plaque (Sheet 1 of 2) Shared-Use Path Figure 9B-2. Example of the Except Bicycles Regulatory Plaque (Sheet 2 of 2) Legend Direction of travel R3-3 R3-3 R3-7aP R3-24 Figure 9B-3. Examples of Bicycle Facilities Adjacent to Back-In Parking Figure 9B-4. Examples of Applications for the Bicycles Yield to Pedestrian Sign R7-107a R7-6 R9-6 R9-6 W11-2 A - Loading Zone R7-7 C - Corner Transit Stop R9-6 R9-6 W11-2 B - Midblock Transit Stop Legend D - Separated Bike Lane at Uncontrolled Crosswalk Direction of travel R1-5 or R1-5a Figure 9B-5. -

State Facilities Action Plan

The Regional Transportation Plan — 2018 Appendix I State Facilities Action Plan May 2018 Puget Sound Regional Council May 2018 Funding for this document provided in part by member jurisdictions, grants from U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration, Federal Highway Administration and Washington State Department of Transportation. PSRC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. For more information, or to obtain a Title VI Complaint Form, see https://www.psrc.org/title-vi or call 206-587-4819. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information: Individuals requiring reasonable accommodations may request written materials in alternate formats, sign language interpreters, physical accessibility accommodations, or other reasonable accommodations by contacting the ADA Coordinator, Thu Le, at 206-464-6175, with two weeks’ advance notice. Persons who are deaf or hard of hearing may contact the ADA Coordinator, Thu Le, through TTY Relay 711. Additional copies of this document may be obtained by contacting: Puget Sound Regional Council Information Center 1011 Western Avenue, Suite 500 Seattle, Washington 98104-1035 206-464-7532 • [email protected] • psrc.org APPENDIX I: State Facilities Action Plan What is the State Facilities Action Plan? PSRC requested the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) to: “…document state efforts to develop an I-5 action plan identifying low cost operational improvements and a clear I-5 preservation plan, improve the flow of HOV lanes, and accelerate seismic retrofits. State plans for future projects beyond those in Connecting Washington will also be covered.” These are some of WSDOT’s most pressing strategic planning issues for highway facilities in the Puget Sound region. -

SR 826/Palmetto Expressway PD&E Study from SR 93/I-75 to the Golden Glades Interchange FM #: 418423-1-22-01 FAP #: 4751 146 P ETDM #: 11241

SR 826/Palmetto Expressway PD&E Study From SR 93/I-75 to the Golden Glades Interchange FM #: 418423-1-22-01 FAP #: 4751 146 P ETDM #: 11241 SYSTEMS INTERCHANGE MODIFICATION REPORT Submitted by: (SIMR) RS&H, Inc. 6161 Blue Lagoon Drive Suite 200 OCTOBER 2014 Miami, Florida 33126 Systems Interchange Modification Report (SIMR) Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PURPOSE AND NEED FOR PROJECT INTRODUCTION The purpose of this project is to develop recommendations for the proposed widening of SR 826 The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) is performing a Project Development and between I-75 and GGI, including the addition of express lanes and a direct system-to-system Environment (PD&E) Study for the SR 826/Palmetto Expressway in Miami-Dade County, Florida. connection between existing express lanes on I-95 and the planned express lanes on SR 826. The Palmetto Expressway PD&E Study limits extend from the SR 93/I-75 Interchange (Mile Post The need for these improvements relates to traffic congestion, systems continuity/connectivity, 15.354) to the Golden Glades Interchange (GGI) (Mile Post 24.572) for a total length of safety and existing design criteria deficiencies. The proposed project will upgrade road facilities approximately 9.2 miles. Figure 1-1 illustrates the location and limits of the project. Through this consistent with current design standards and provide additional capacity to meet the anticipated project, FDOT proposes to widen SR 826 mainline from I-75 to Golden Glades Interchange to future traffic growth and multi-modal transportation demand within the Palmetto Expressway provide additional lanes that could serve as general use lanes or managed lanes (express lanes). -

Interchange Modification Report

Interchange Modification Report I-75 at Bill Gardner Parkway (CR 650) City of Locust Grove in Henry County, Georgia Prepared for: City of Locust Grove In coordination with: Georgia Department of Transportation Prepared by: February 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document is an Interchange Modification Report (IMR) which presents an analysis of proposed improvements to the I-75 interchange at Bill Gardner Parkway (CR 650) located in the City of Locust Grove, Henry County Georgia. Due to existing and projected operational deficiencies at this location as demonstrated in this report, the analysis compares three build alternatives to the future (2035) no-build scenario. The three alternatives include: Build Alternative 1 – Single Point Urban Interchange (SPUI), Build Alternative 2 – Diverging Diamond Interchange (DDI), and Build Alternative 3 – Triple Left Turns on Southbound Off-Ramp. All 2035 Build alternatives analyzed as part of this IMR assume that the City of Locust Grove/Henry County sponsored Special Purpose Local Options Sales Tax (SPLOST) Bill Gardner Parkway widened project (with some modification) is completed. The modified Bill Gardner Parkway widening project used for the 2035 Build analyses assumes the widening from two (2) to four (4) lanes from the I-75 southbound ramps to Strong Rock Boulevard, and from four (4) to six (6) lanes from the I-75 northbound ramps to Tanger Boulevard. A summary of the operations analysis is provided in Table ES.1 in tabular format. The operations analysis results are provided in vehicle delay (seconds) and related to the corresponding level of service (LOS) for the AM and PM peak hours at the Bill Gardner Parkway interchange.