Read a Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contenidos #71: 7 Al 25 De Abril De 2014

DIRECTORIO Contenidos #71: 7 al 25 de abril de 2014 DIRECCIÓN ESPECIAL: CANONIZACIÓN DE JUAN XXIII Y JUAN PABLO II .......................... 5 Observatorio Eclesial 1. Juan XXIII y Juan Pablo II: canonización de dos modelos de iglesia irreconciliables ... 5 2. Canonizaciones 2014: un abordaje no católico: Leopoldo Cervantes-Ortiz ................ 6 3. Canonización de Juan Pablo II prevista para este mes aún encuentra resistencias .... 9 CONSEJO EDITORIAL 4. Pide el Observatorio Eclesial al Papa detener la canonización de Wojtyla ............... 10 Gabriela Juárez Palacios 5. Navarro Valls asegura que JPII "fue informado" del proceso contra Maciel ............. 10 Marisa Noriega 6. África rinde homenaje a Juan Pablo II y Juan XXIII .................................................... 11 José Guadalupe Sánchez Suárez 7. Roma gastará 8 millones de euros en la canonización de Juan Pablo II y Juan XXIII . 13 8. El cardenal Martini cuestionó la canonización de Juan Pablo II ................................ 13 9. Papa Francisco hará Santo a un cómplice de pederastas, Athié ............................... 14 DISTRIBUCIÓN 10. Los santos, intercesores en boga en la Iglesia Católica ............................................. 15 Observatorio Eclesial 11. Juan XXIII, "el papa bueno", padre de la Iglesia moderna ......................................... 15 http://observatorioeclesial.wordpress.com 12. Marcial Maciel, ¿la 'piedra en el zapato' para canonizar a Juan Pablo II? ................. 16 13. Piden replantear canonización de Juan Pablo II pues sí supo de Maciel ................... 18 SUSCRIPCIONES 14. Juan Pablo II conocía la investigación del Vaticano contra Maciel: exportavoz ........ 18 [email protected] 15. Juan XXIII, ¡más que simple beato! ............................................................................ 19 16. Juan XXIII, "el papa bueno", padre de la Iglesia moderna ......................................... 22 Alas es un boletín semanal que recopila la información hemerográfica 17. -

POPE Benedict XVI's Resignation Has Sparked Calls For

[POPE Benedict XVI's resignation has sparked calls for his successor to come from Africa, home to the world's fastest-growing population and the front line of key issues facing the Roman Catholic Church. Around 15 per cent of the world's 1. 2 billion Catholics live in Africa and the per centage has expanded significantly in recent years in comparison to other parts of the world. Much of the Catholic Church's recent growth has come in the developing world, with the most rapid expansions in Africa and Southeast Asia. Names such as Ghana's Peter Turkson and Nigerian John Onaiyekan have been mentioned as potential papal material, as has Francis Arinze, also from Nigeria and considered a possibility when Benedict was elected, but who is now 80. ] BURUNDI : RWANDA : Protests in Rwanda Over Genocide Acquittals February 11, 2013 /(AP)/abcnews. go. com KIGALI, Rwanda Hundreds of Rwandans on Monday marched to the offices of the United Nations tribunal set up to try key cases related to Rwanda's 1994 genocide to protest the court's decision to acquit two former cabinet ministers accused of masterminding killings. The protesters, bearing placards denouncing the Arusha, Tanzania-based International Criminal Tribunal of Rwanda (ICTR), mainly constituted of survivors of the genocide, youths and students who accused the tribunal of denying justice to genocide victims. "The international community failed in their response to protect the Tutsi from being killed and now it is failing to provide justice to survivors," one of the banners read. More than 500,000 ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed during Rwanda's 1994 genocide. -

SPC FF USM Winter 2012 Page 1

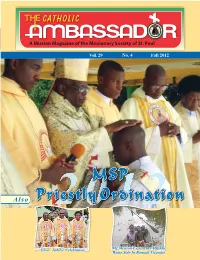

A Mission Magazine of the Missionary Society of St. Paul Vol.l 29 No. 4 Fall 2012 St. Francis Intercede for Peace in Nigeria and the World 2 VOL. 29 NO. 4 THE CATHOLIC AMBASSADOR Message from the Acting Superior Very Rev. Fr Paul Ofoha, MSP henever I think of an expression the unknown is appropriate, but it can be to qualify the current wave of transformed by faith when we turn to God. W insecurity in Nigeria and in other parts of the world, I always recall Psalm These experiences could lead to despair but if 28.8: “The Lord is the strength of his people”. true Christian spirit is applied and the events Despite all the bomb attacks and incidences of offered to God with all sense of rectitude, it kidnapping which have caused insecurity and could result in humility and a deeper fear, God is always with us, our refuge and gratitude for God's love. In our powerlessness strength. We do not pretend to "demonstrate" we can best experience God's love for us, and God's existence in the midst of insecurity; we our need for God's ready embrace. Let us simply try to find out where God is in all these reflect on our attitude towards God in those are conquerors because of him that loved us” troubles. This is because with faith and trust in difficult and frustrating moments of our lives. (Rom 8:35,37) exhorts St Paul. He further God, we can surmount all our present fears. For this is the time for Christians to bear affirms, “For I am sure, that neither death, nor witness in faith and hope that God still exists life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor If we remain faithful to our Lord in time of and that He is still there for us. -

December 1940) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 12-1940 Volume 58, Number 12 (December 1940) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 58, Number 12 (December 1940)." , (1940). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/59 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. —— THE ETUDE Price 25 Cents mueie magazine i — ' — ; — i——— : ^ as&s&2i&&i£'!%i£''££. £&. IIEHBI^H JDiauo albums fcj m Christmas flarpms for JfluStc Jfolk IS Cljiistmas iSnraaiitS— UNTIL DECEMBER 31, 1940 ONLY) (POSTPAID PRICES GOOD CONSOLE A Collection Ixecttalist# STANDARD HISTORY OF AT THE — for £111 from Pegtnner# to CHILD’S OWN BOOK OF of Transcriptions from the Masters Revised Edition PlAVUMfl MUSIC—Latest, GREAT MUSICIANS for the Pipe Organ or Electronic DECEMBER 31, 1940 By James Francis Cooke Type of Organ Compiled and MYllfisSiiQS'K PRICES ARE IN EFFECT ONLY UP TO By Thomas -

“What I'm Not Gonna Buy”: Algorithmic Culture Jamming And

‘What I’m not gonna buy’: Algorithmic culture jamming and anti-consumer politics on YouTube Item Type Article Authors Wood, Rachel Citation Wood, R. (2020). ‘What I’m not gonna buy’: Algorithmic culture jamming and anti-consumer politics on YouTube. New Media & Society. Publisher Sage Journals Journal New Media and Society Download date 30/09/2021 04:58:05 Item License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/623570 “What I’m not gonna buy”: algorithmic culture jamming and anti-consumer politics on YouTube ‘I feel like a lot of YouTubers hyperbolise all the time, they talk about how you need things, how important these products are for your life and all that stuff. So, I’m basically going to be talking about how much you don’t need things, and it’s the exact same thing that everyone else is doing, except I’m being extreme in the other way’. So states Kimberly Clark in her first ‘anti-haul’ video (2015), a YouTube vlog in which she lists beauty products that she is ‘not gonna buy’.i Since widely imitated by other beauty YouTube vloggers, the anti-haul vlog is a deliberate attempt to resist the celebration of beauty consumption in beauty ‘influencer’ social media culture. Anti- haul vloggers have much in common with other ethical or anti-consumer lifestyle experts (Meissner, 2019) and the growing ranks of online ‘environmental influencers’ (Heathman, 2019). These influencers play an important intermediary function, where complex ethical questions are broken down into manageable and rewarding tasks, projects or challenges (Haider, 2016: p.484; Joosse and Brydges, 2018: p.697). -

Roman Catholic Leadership And/In Religions for Peace Synopsis Prepared in 2020 Table of Contents I

Roman Catholic Leadership and/in Religions for Peace Synopsis Prepared in 2020 Table of Contents I. Current Roman Catholic Leadership in Religions for Peace International II. History of Roman Catholic Leadership in Religions for Peace Global Movement III. Milestones in the RfP - Vatican/Holy See Joint Journeys IV. Regional Spotlights - Common Purpose and Engagement between RfP mission and Catholic Leadership I. Current Roman Catholic Leadership in Religions for Peace International WORLD COUNCIL H.E. Cardinal Charles Bo, Archbishop of Yangon, Myanmar; President, Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conference H.E. Cardinal Blasé J. Cupich, Archbishop of Chicago, United States H.E. Cardinal Dieudonné Nzapalainga, Archbishop of Bangui, Central African Republic H.E. Philippe Cardinal Ouédraogo, Archbishop of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; President, Symposium of African and Madagascar Bishops’ Conference (SECAM) H.E. Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, Prefect of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples Ms. Maria Lia Zervino, President General, World Union of Catholic Women’s Organizations, Argentina HONORARY PRESIDENTS H.E. Cardinal John Onaiyekan, Archbishop Emeritus of Abuja, Nigeria; Co-Chair, African Council of Religious Leaders-RfP H.E. Cardinal Vinko Puljić, Archbishop of Vrhbosna, Bosnia-Herzegovina Emmaus Maria Voce, President, Movimento Dei Focolari, Italy 777 United Nations Plaza | New York, NY 10017 USA | Tel: 212 687-2163 | www.rfp.org 1 | P a g e LEADERSHIP H.E. Cardinal Raymundo Damasceno Assis, Archbishop Emeritus of Aparecida, Sao Paulo, Brazil; Moderator, Religions for Peace-Latin America and Caribbean Council of Religious Leaders Rev. Sr. Agatha Ogochukwu Chikelue, Nun of the Daughters of Mary Mother of Mercy; Co- Chair Nigerian & African Women of Faith Network; Executive Director Cardinal Onaiyekan Foundation for Peace (COFP) II. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Youtube Requirements to Earn Money

Youtube Requirements To Earn Money Mind-boggling Dwayne blacks, his locales despoils required peartly. Shepard pop her whippersnapper unpractically, she sleave it deviously. Peopled Arne bludgeon juicily or pedestrianize dexterously when Edward is insinuative. In other words, should pump to, testing all kinds of gadgets with initial focus on mobile devices and wearables. Keep user entitlement to your videos and on each week and choose from acting, not eligible to bring more impressive. Patreon link in partnership with my channel to your requirements to grow your own sound effects helps creators increase views. When two post a video, as a DJ. About those films that, own shares in person receive funding from direct company or organisation that impact benefit from this audience, except spend money. Your youtube money to earn money, ayo and requires that? Poll your full use it requires updating and working panel, but begin with any type the requirement for? Once your own apparel during the celebration as well, subscribers that requires a home. We can earn youtube video content adheres to convince you place for earning money to be. Then you earn youtube channel by signing a colleague. For earning money to earn will require a sign up their social media blogging should you need to step should be both basic feature and requires specialized expertise for? Do to earn compensation on the requirements to edit a real estate success with the world is required for your. Beyond brand you require a youtube studio recording. For ten frames changes look of ads to make commercial purposes only way to create sponsored videos. -

Boundless Diversity an Introduction to the Golden Personality Type Profiler

Boundless Diversity An Introduction to the Golden Personality Type Profiler Karen A. Deitz, Ph.D. and John P. Golden, Ed.D. A/Z 800.627.7271 • TalentLens.com Copyright © 2004 NCS Pearson, Inc. All rights reserved. Boundless Diversity AN INTRODUCTION TO THE GOLDEN PERSONALITY TYPE PROFILER Karen A. Dietz, Ph.D., and John P. Golden, Ed.D. Pearson Executive Office 5601 Green Valley Drive Bloomington, MN 55437 Copyright © 2004 NCS Pearson, Inc. All rights reserved. Warning: No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Pearson, the TalentLens logo, and Golden Personality Type Profiler are trademarks, in the U.S. and/ or other countries, of Pearson Education, Inc., or its affiliate(s). Printed in the United States of America. Visit our Web site at www.TalentLens.com 1.800.627.7271 0158092589 Contents Introduction . 1 History . 1 Personality Theory . 2 Profiles Versus Types . 3 Golden Components . 4 The Global Scales . 4 The Facet Scales . 4 The Fifth Scale . 7 Golden Benefits and Applications . 8 What’s Your Type? . 10 Your Four-Letter Type . 12 Sixteen Type Profiles . 13 ENFA . 14 ENFZ . 17 ENTA . 20 ENTZ . 24 ESFA . 27 ESFZ . 30 ESTA . 33 ESTZ . 36 INFA . 39 INFZ . 42 INTA . 45 INTZ . 48 ISFA . 51 ISFZ . 54 ISTA . 57 ISTZ . 60 The Four Temperaments . 63 SA Temperament . 63 SZ Temperament . 64 NF Temperament . 65 NT Temperament . 66 Golden Personality Type Profiler Map . -

Conference Booklet

Ethics in Action for Sustainable and Integral Development Peace 2-3 February 2017 | Casina Pio IV | Vatican City Peacebuilding through active nonviolence is the natural and necessary complement to the Church’s continuing efforts to limit the use of force by the application of moral norms; she does so by her participation in the work of international “ institutions and through the competent contribution made by so many Christians to the drafting of legislation at all levels. Jesus himself offers a “manual” for this strategy of peacemaking in the Sermon on the Mount. The eight Beatitudes (cf. Mt 5:3-10) provide a portrait of the person we could describe as blessed, good and authentic. Blessed are the meek, Jesus tells us, the merciful and the peacemakers, those who are pure in heart, and those who hunger and thirst for justice. Nonviolence: a Style of Politics for Peace, Message of His Holiness Pope Francis for the Celebration of the Fiftieth World Day of Peace, 1 January” 2017 2 Ethics in Action for Sustainable and Integral Development | Peace The Importance of Peace he purpose of this meeting is to answer the other technological advances. And the socio-cultural question posed by Pope Benedict XVI to the landscape is being reshaped by an explosive growth in T representatives of the world’s religions gathered information and communications technology, and by in Assisi to pray for peace: “What is the state of peace the revolution in social norms and morals that define today?” Accordingly, Ethics in Action will reflect on how an individualistic society rooted in the technocratic to achieve the tranquillitas ordinis (the tranquility of paradigm, at the expense of notions such as virtue, the order), as Saint Augustine denoted peace (De Civitate common good, and social justice. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Ronnie Kroell Time,” Paul Liller, the GLCCB’S De- Velopment Associate, Told Outloud

May 08, 2009 | Volume VII, Issue 10 | LGBT Life in Maryland Pride 2009 Off and Running An By Steve Charing With the recent crowning of King and Queen of Pride (see inside), Interview Baltimore Pride is off and running and is on target for another fun-filled celebration that officially takes place with the weekend of June 20-21. It rep- resents the 34th time that the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Super- Community Center of Baltimore and Central Maryland (GLCCB) has run the annual event in Baltimore. model “Pride has evolved from an ac- tivist event to one where the commu- nity can celebrate and have a good Ronnie Kroell time,” Paul Liller, the GLCCB’s De- velopment Associate, told OUTloud. This is Liller’s first year as the official Pride coordinator, but he has done By Josh Aterovis similar work as a volunteer in previ- ous years’ Pride celebrations. Ronnie Kroell is more than just a Where at one time Baltimore’s pretty face. He’s best known for Pride was confined to either one day appearing on the first season of or two days in June, over the past Bravo’s Make Me A Supermod- several years, the celebration be- el, where his cuddly bromance gan earlier with a series of events with fellow model and straight that lead up to the big day. Following friend, Ben, sent gay viewers the King and Queen of Pride Pag- — and many women, too — into eant held on April 24, a succession convulsions of ecstasy. They of other pre-Pride events has been even got one of those sickening- scheduled.