To Download Free Ebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ARIZONA ROUGH RIDERS by Harlan C. Herner a Thesis

The Arizona rough riders Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Herner, Charles Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 02:07:43 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551769 THE ARIZONA ROUGH RIDERS b y Harlan C. Herner A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1965 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of require ments for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under the rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of this material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: MsA* J'73^, APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: G > Harwood P. -

The New Mexican Review, 06-30-1910

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-30-1910 The ewN Mexican Review, 06-30-1910 New Mexican Printing Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news Recommended Citation New Mexican Printing Co.. "The eN w Mexican Review, 06-30-1910." (1910). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sfnm_news/7985 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Fe New Mexican, 1883-1913 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW MEXICAN REVIEW, FORTY-SEVE- N YEAR SANTA EE. N. M., THURSDAYS JUJSE 30 1910. NO 14 ed in Bplendid health until today. mountains at Red River, Taos county, L Divorce Suit. CAUGHT BY THE OF New Mexico. - Suit for divorce was filed in San I "The gold band encircling the pen, Juan county by Mrs, O. Grimes, vs. was made from bullion taken from Roscue Grimes, whom she charges the mines of Taos county. SANDS Made B. MEET T with desertion and abandonment. The InFHOIET QUICK and presented by George couple were married In March. 1907. Paxton, a resident ot Red River, New Sullivan and' Ervlen Back. Mexico." There was rather a sad story In con Will Territorial Engineer Sullivan' and President and His Prede- Two Youths Die Horrible President Taft Does Not Well Known Trader'Murder-e- d Apportion Delegates nection with the quill pen, with Land Commissioner Ervlen have re- Hands in Grande Want which the President state- at Pueblo Bonito for Constitutional turned fro man extensive on land cessor Will Shake Death Rio at Bryan to Write signed the trip hood bill. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory. -

We Believe in the Spirit of the American West to the Point ©2010 Buffalo Bill Historical Center (BBHC)

BUFFALO BILL HISTORICAL CENTER n CODY, WYOMING n SUMMER 2010 n See our new Credo. Page 19 We believe in the spirit of the American West To the point ©2010 Buffalo Bill Historical Center (BBHC). Written permission is required to copy, reprint, or distribute Points West materials in any medium or format. All photographs in Points West are BBHC photos unless otherwise noted. Questions about image rights and reproduction should be directed to Rights and n the cover of this issue of Reproductions, [email protected]. Bibliographies, works Points West is a selection cited, and footnotes, etc. are purposely omitted to conserve O space. However, such information is available by contacting the of photographs from stories editor. Address correspondence to Editor, Points West, BBHC, 720 within these pages along with Sheridan Avenue, Cody, Wyoming 82414, or [email protected]. the words, “We believe in the Senior Editor: Spirit of the American West.” Mr. Lee Haines Believe me when I tell you: Managing Editor: You’re going to see a lot more Ms. Marguerite House By Bruce Eldredge of this phrase! Assistant Editor: Executive Director Ms. Nancy McClure At our January Board of Designer: Trustees meeting, we adopted a statement of what we do Ms. Lindsay Lohrenz and what we believe (see page 19). We call it a “Credo,” Contributing Staff Photographers: which is a set of beliefs or ideals conveyed in a concise Ms. Chris Gimmeson, Ms. Nancy McClure, Dr. Charles Preston, Ms. Emily Buckles written form; a credo defines the boundaries within which a group of people operate. In the case of the Buffalo Bill Historic Photographs/Rights and Reproductions: Mr. -

Celebrating Native Innovation CHICKASAW

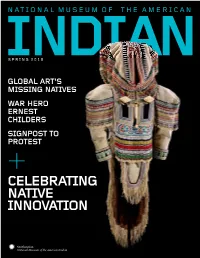

NATIONAL MUSEUM Of ThE AMERICAN INDIANSPRING 2018 globAl Art’s MIssINg NAtIves WAr Hero erNEST cHIlDers sIgNPOST to Protest + celebrAtINg NAtIve INNovAtIoN CHICKASAW CULTURAL CENTER LIVING CULTURE Visit the CHICKASAW CULTURAL CENTER to explore and learn about the unique history and vibrant culture of the Chickasaw people. Join us for exhibits, films, demonstrations, storytelling and special events at one of the largest and most extensive cultural centers in the United States. SULPHUR, OK WWW.CHICKASAWCULTURALCENTER.COM IDYLLWILD ARTS Native American Workshops and Festival June 18-July 2,2018 Scholarships for Native American adults and kids available for all workshops! Register Now! idyllwildarts.org/nativearts [email protected] 951-468-7265 Contents SPRING 2018 vol. 19 No. 1 22 34 a gallery oF iNveNtioN th the Mark oF the 45 From sunglasses to chewing gum, the First Peoples Indian soldiers played an outsized role in the famed were there first. 45th “Thunderbird” Division, comprising the National Guards of four southwestern states. They left their imprint on the annals, and the public face, of the U.S. 39 PlayiNg CroPetitioN, the gaMe Army of World War II. oF survival Maximize crop yield or nutritional value? Compete or share? These are choices youngsters make in a new touch-table game as they discover the principles of 24 Native agriculture. WilliaM PolloCk, artist aNd rough rider This multi-talented Pawnee student greatly impressed his teachers at Haskell Institution with his artistic skill. 42 exhibitioNs & eveNts CaleNdar 8 He also impressed his commander in the “Rough Rid- Where are the Native artists? ers” of the Spanish–American War, Lt. -

Book Reviews

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 85 Number 2 Article 4 4-1-2010 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation . "Book Reviews." New Mexico Historical Review 85, 2 (2010). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/ vol85/iss2/4 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Book Reviews No Settlement, No Conquest: A History of the Coronado Entrada. By Rich- ard Flint. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008. xviii + 358 pp. Maps, glossary, notes, bibliography, index. $29.95 cloth, ISBN 978-0-8263- 4362-8.) Archival research is time consuming and often unproductive. So it is no wonder that in our “publish or perish” world, many of us look for an easier way—a “sophisticated” theoretical argument short on empirical specificity. Richard Flint’s book, No Settlement, No Conquest, is a delightful reminder of the rewards of painstaking research. Flint’s two previous books on the Coronado expedition, Documents of the Coronado Expedition, 1539–1542: “They Were Not Familiar with His Majesty, nor Did They Wish to Be His Subjects” (2005), and Great Cruelties Have Been Reported: The 1544 Investi- gation of the Coronado Expedition (2002) also exemplify the benefits of dili- gent research. In No Settlement, No Conquest, Flint draws from a vast array of primary sources to detail the events of the Coronado expedition and its aftermath. -

Cowboys and Western Figures

Shirley Papers 37 Research Materials, Cowboy & Western Figures Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Cowboys and Western Figures Buckskin Joe 109 Artifacts 110 1 Book: Buckskin Joe or The Trapper Guide, by Silingsby 2 Business Cards 3 Certificates, 1856, 1890, 1884 4 Contracts, 1879, 1880, 1888 Correspondence 5 Christmas card, 1912 6 Correspondence 1888, 1910 7 Correspondence with Dr. Vance J. Hoyt, 1949 Diary 8 Union Army 1859 9 Sections of Civil War diary of Edward Jonathan Hoyt Ephemera 10 Souvenir pictures 11 Hand signal interpretations Newspaper clippings 12 Newspaper clippings 1908, 1912 Photographs 13 Portraits of Buckskin Joe aka Edward Jonathan Hoyt 14 Snapshots of Buckskin Joe 15 Buckskin Joe and Bill Palmer Central America 16 Buckskin Joe & Wife, Hoyt home, 1907 17 Cabin in Central America 18 Central America hotel 19 First Wild West Show band, 1885 20 Palace Hotel construction, 1889 21 “Attack on Indians” Wild West Show, 1892 22 First Wild West Show band, 1885 23 Tight rope walking, 1887 24 Wild West colleagues-Annie Oakley, Addie Carlisle, Ella Lance Hoyt Documents 25 Reminiscences about Buckskin Joe by grandson 26 Scrapbook 27 Title Bond, 1881 28 Newspaper clipping-articles by Lance Hoyt Buffalo Bill William F. Cody 111 1 Articles, 1903-1907 2 Articles, 1937, 1961-1970 3 Articles, 1970-1981 4 Articles, 1982-1984 5 Articles, 1949, 1991-2002 112 1 Play: “Life on the border’, 1965 Buffalo Bill Wild West Show 2-3 Notebook (assembled by Glenn Shirley) Shirley Papers 38 Research Materials, Cowboy & Western Figures Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Programs 4 1983 5 1895 6 1899 7 1907 8 1907 9 1908 Custer, George Armstrong 113 1-6 Custer & the West articles 114 1-3 Custer & the West articles Eaton, Frank “Pistol Pete 4-6 Articles, 1904-2001 115 1-2 Articles, 1904-2001 Gray, Otto 116 1 78 RPM records 2 Articles, 1958, 1992, 1994, n. -

Thesis Final Draft Revised

SOUNDS OF PAYNE COUNTY A MUSEUM EXHIBITION PROPOSAL By CYNTHIA INGHAM Bachelor of Arts in History West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX 2007 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS December, 2013 SOUNDS OF PAYNE COUNTY A MUSEUM EXHIBITION PROPOSAL Thesis Approved: Dr. Bill Bryans Thesis Adviser Dr. Ron McCoy Dr. Lowell Caneday ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For my friends and family, I could not have achieved this without your love and support. For my former teachers and professors, Thank you for your encouragement and for passing on your knowledge and sharing your passion for learning. iii Acknowledgements reflect the views of the author and are not endorsed by committee members or Oklahoma State University. Name: CYNTHIA INGHAM Date of Degree: DECEMBER, 2013 Title of Study: SOUNDS OF PAYNE COUNTY: A MUSEUM EXHIBTION PROPOSAL Major Field: HISTORY Abstract: The following pages contain a history of the musicians and music that have come out of Payne County, Oklahoma and a description of how to use that history in a museum setting. The history incorporates the contributions of amateur and professional musicians that either grew up in the area or gained major influence from living in the county. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................1 II. PAYNE COUNTY’S GIFTED AMATEURS ..........................................................4 III. THE PROFESSIONALS .......................................................................................32 IV. SOUNDS OF PAYNE COUNTY: A MUSEUM EXHIBIT .................................50 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................68 APPENDICES .............................................................................................................81 v CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Oklahoma! Where the wind comes sweeping’ down the plain. -

American West University of Oklahoma Press

American West UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA PRESS OUPRESS.COM American West CONTENTS American Indian ...............................1 Art & Photography .............................3 Biography & Memior ............................7 Environment .................................12 History .....................................13 Literature & Fiction ............................19 Military History ..............................20 The Arthur H. Clark Company ....................22 Chickasaw Press ..............................26 Cherokee National Press ........................29 Best Sellers ..................................30 Forthcoming Books Spring 2011 ..................33 For more than eighty years, the University of Oklahoma Press has published award-winning books about the West and we are proud to bring to you our new American West catalog. The catalog features the newest titles from both the University of Oklahoma Press and The Arthur H. Clark Company, an imprint of OU Press. For a complete list of titles available from OU Press, please visit our website at oupress.com. For a complete list of The Arthur H. Clark Company titles, please visit ahclark.com. We hope you enjoy this catalog and appreciate your continued support of the University of Oklahoma Press. Price and availability subject to change without notice. UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA PRESS OUPRESS.COM · OUPRESSBLOG.COM ON THE COVER: RoDEO CowGIRLS BESSIE AND RubY DICKEY, TucumcaRI, NEW MEXICO, RoDEO, CIRca 1918. COURTESY NatioNAL cowboY AND WESTERN HERitaGE MUSEUM, MCCARROLL FAMILY TRUST COLLECTION, RC2006.076.045 oupress.com american indian 1 American Indian A GUIDE TO THE INDIAN TRIBES OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST Third Edition By Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins $26.95 Paper · 978-0-8061-4024-7 · 448 pages The Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest inhabit a vast region extending from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean and from California to British Columbia. -

388 Jessie Elizabeth Randolph Moore by Muriel H

Vol. 34 No. 4 The Great Seal of the Chickasaw Nation by the Editor ------------------------------- 388 Jessie Elizabeth Randolph Moore by Muriel H. Wright ------------------------------ 392 Missionary Tour in the Chickasaw Nation By Reverend Hillary Cassal ------------------------------------------------------ 397 The Balentines, Father and Son by Carolyn Thomas Foreman ----------------------- 417 Carl Sweezy, Arapaho Artist by Althea Bass ------------------------------------------- 429 The Story of an Oklahoma Cowboy by Leslie A. McRill ----------------------------- 432 A Spanish “Arrastra” in the Wichita Mountains By W. Eugene Hollon ------------------------------------------------------------- 443 The Osage Indians and the Liquor Problem before Statehood By Frank F. Finney ---------------------------------------------------------------- 456 Events Leading to the Treaties of Franklin and Pontotoc By Muriel H. Wright --------------------------------------------------------------- 465 Notes and Documents ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 484 Book Reviews -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 503 Necrology Albert Leroy McRill by Leslie McRill ------------------------------------------ 506 Louis Seymour Barnes by George H. Shirk ------------------------------------ 507 John Chouteau by J.M. Richardson ---------------------------------------------- 508 Minutes --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 509 THE GREAT -

Points-West 1998.09.Pdf

CONTENTS 3 WILLIAM R. LEIGH IN CODY COUNTRY 6 THE POWER OF IMAGES: Indian Revitalization ne of the many ways that the Historical Presents Unbounded Possibilities .,,,.""..,,.,. ii :,i Center can benefit from its donors is COL. CODY, THE ROUGH RIDERS AND THE 'ir,u,. ":;1' through the vehicle oi planned gifts. What I SPANISH AMERICAN WAR is a planned gift? Essentially, it is a way for donors to make gilts to charitable organizations in return for 12 THE IRMA: "Just the Swellest Hotel That Ever favorable tax and other linancial benefits. In other Happened" words, lifetime gifts provide long-term bene[its to both 15 CHEYENNE DOG SOLDIERS: Warrior Exploits the donor and the recipient institution. Survive in Ledger Drawings Planned gifts fall into three general categories: bequests, ouright gifts and life income gifts. The WESTERN DESIGN: An Ever-lncreasing Sphere I6 ol Influence latter include charitable remainder unitrusts, charitable remainder annuity trusts, life and deferred INSPIRED BY NATURE. Weiss Purchase Award gift annuities, charitable lead trusts as well as:gifts of I8 Winner Charles Fritz life insurance and real estate. r ', :ri:.:.: l.iiiti:i::lll::r.d:, WE'VE COME A LONG WAt BABY-Remembering Each of these different gift vehide.!111t!$11$ 19 the beginnings of the Patrons Ball tages, depending on the individual,donOf$fir. situation. Whether they be guaranteedrtfi$C( KLEIBER, PACHMAYR WORKS FEATURED 20 NEW DISPLAY and tax savings from a gift annuitll,orl O4: IN large capital gains on appreciated':,pf.ope,!lV,: 21 BIT BY BIT: Ned and Jody Martin Create Bit advanrages can materially benefit the donor \thile and Spur Makers in the Vaquero Tradition providing for a favorice charity. -

INDIANSPRING 2018 Global Art’S Missing Natives War Hero ERNEST CHILDERS Signpost to Protest + Celebrating Native Innovation CHICKASAW

NATIONAL MUSEUM Of ThE AMERICAN INDIANSPRING 2018 globAl Art’s MIssINg NAtIves WAr Hero erNEST cHIlDers sIgNPOST to Protest + celebrAtINg NAtIve INNovAtIoN CHICKASAW CULTURAL CENTER LIVING CULTURE Visit the CHICKASAW CULTURAL CENTER to explore and learn about the unique history and vibrant culture of the Chickasaw people. Join us for exhibits, films, demonstrations, storytelling and special events at one of the largest and most extensive cultural centers in the United States. SULPHUR, OK WWW.CHICKASAWCULTURALCENTER.COM IDYLLWILD ARTS Native American Workshops and Festival June 18-July 2,2018 Scholarships for Native American adults and kids available for all workshops! Register Now! idyllwildarts.org/nativearts [email protected] 951-468-7265 Contents SPRING 2018 vol. 19 No. 1 22 34 a gallery oF iNveNtioN th the Mark oF the 45 From sunglasses to chewing gum, the First Peoples Indian soldiers played an outsized role in the famed were there first. 45th “Thunderbird” Division, comprising the National Guards of four southwestern states. They left their imprint on the annals, and the public face, of the U.S. 39 PlayiNg CroPetitioN, the gaMe Army of World War II. oF survival Maximize crop yield or nutritional value? Compete or share? These are choices youngsters make in a new touch-table game as they discover the principles of 24 Native agriculture. WilliaM PolloCk, artist aNd rough rider This multi-talented Pawnee student greatly impressed his teachers at Haskell Institution with his artistic skill. 42 exhibitioNs & eveNts CaleNdar 8 He also impressed his commander in the “Rough Rid- Where are the Native artists? ers” of the Spanish–American War, Lt.