The US Department Store Industry in the 1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Controversial NAS, All's Quiet on the National Front

WELCOME BACK ALUMNI •:- •:• -•:•••. ;:: Holy war THE CHRONICLE theo FRIDAY. NOVEMBER 2, 1990 DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA Huge pool of candidates Budget crunch threatens jazz institute leaves Pearcy concerned Monk center on hold for now r- ————. By JULIE MEWHORT From staff reports Ronald Krifcher, Brian Ladd, performing and non-performing An exceptionally large can David Rollins and Steven The creation ofthe world's first classes in jazz. didate pool for the ASDU Wild, Trinity juniors Sam conservatory for jazz music is on The Durham city and county presidency has President Con Bell, Marc Braswell, Mandeep hold for now. governments have already pur nie Pearcy skeptical of the in Dhillon, Eric Feddern, Greg During the budgeting process chased land for the institute at tentions of several of the can Holcombe, Kirk Leibert, Rich this summer, the North Carolina the intersection of Foster and didates. Pierce, Tonya Robinson, Ran General Assembly was forced to Morgan streets, but officials do Twenty-five people com dall Skrabonja and Heyward cut funding for an indefinite not have funds to begin actual pleted declaration forms Wall, Engineering juniors period to the Thelonious Monk construction. before yesterday's deadline. Chris Hunt and Howard Institute. "Our response is to recognize Last year only four students Mora, Trinity sophomores The institute, a Washington- that the state has several finan ran for the office. James Angelo, Richard Brad based organization, has been cial problems right now. We just Pearcy said she and other ley, Colin Curvey, Rich Sand planning to build a music conser have to continue hoping that the members of the Executive ers and Jeffrey Skinner and vatory honoring in downtown budget will improve," said Committee are trying to de Engineering sophomores Durham. -

Finding Thalhimers Online

HUQBt (Download) Finding Thalhimers Online [HUQBt.ebook] Finding Thalhimers Pdf Free Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1290300 in Books Dementi Milestone Publishing 2010-10-16Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 10.14 x 1.17 x 7.30l, 2.08 #File Name: 0982701918274 pages | File size: 71.Mb Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt : Finding Thalhimers before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Finding Thalhimers: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Indepth Look at an American Success StoryBy Jennifer L. SetterstromI thought I was getting a book about the history of Thalhimers,a department store in Richmond Virginia, but it is so much more! Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt has done a superb job in tracing her family roots all the way back to the first Thalhimer who came to America from Germany to eventually begin a business that would grow and expand and endure for decades. I grew up with Thalhimers, so this was particularly interesting to me. The book covers not only a long lineage of Thalihimer business men(and their families) but gives the reader a good look at Richmond history. How the final demise of such an iconic part of Richmond came to be is a reflection of the fate of most of the department stores we baby boomers grew up with. A satisfying read with a touch of nostalgia, and truly a through well told story of the American dream.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. -

Notice of Proposed Second Administrative Settlement and Request for Public Comment

http://frwebgate3.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin.. .cID=7723205640+0+0+0&WAISaction=retrieve Superfund Records Confer [Federal Register: September 10, 2002 (Volume 67, Number 175)] ol 11: faff <&&*>! [Notices] BREAK: [Page 57426-57429] OTHER: From the Federal Register Online via GPO Access [wais.access.gpo.gov] [DOCID:frlOse02-81] ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY [FRL-7373-4] Proposed Second Administrative Cashout Settlement Under Section 122(g) of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act; In Re: Beede Waste Oil Superfund Site, Plaistow, NH AGENCY: Environmental Protection Agency. ACTION: Notice of proposed second administrative settlement and request for public comment. [[Page 57427]] SUMMARY: In accordance with section 122(i) of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. 9622(i), notice is hereby given of a proposed second administrative settlement for recovery of past and projected future response costs concerning the Beeda Waste Oil Superfund Site in Plaistow, New Hampshire with the settling parties listed in the Supplementary Information portion of this notice. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency--Region I (EPA) is proposing to enter into a second de minimis settlement agreement to address claims under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, as amended (^CERCLA11), 42 U.S.C. 9601 et seq. Notice is being published to inform the public of the proposed second settlement and of the opportunity to comment. This second settlement, embodied in a CERCLA section 122(g) Administrative Order on Consent C'AOC'1), is designed to resolve each settling party's liability at the Site for past work, past response costs and specified future work and response costs through covenants under sections 106 and 107 of CERCLA, 42 U.S.C. -

Colors for Bathroom Accessories

DUicau kji oLctnufcirus DEC 6 1937 CS63-38 Colors (for) Bathroom Accessories U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DANIEL C. ROPER, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS LYMAN J. BRIGGS, Director COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 Effective Date for New Production, January I, 1938 A RECORDED STANDARD OF THE INDUSTRY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1S37 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 5 cents U. S. Department of Commerce National Bureau of Standards PROMULGATION of COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 for COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES On April 30, 1937, at the instance of the National Retail Dry Goods Association, a general conference of representative manufacturers, dis- tributors, and users of bathroom accessories adopted seven commercial standard colors for products in this field. The industry has since ac- cepted and approved for promulgation by the United States Depart- ment of Commerce, through the National Bureau of Standards, the standard as shown herein. The standard is effective for new production from January 1, 1938. Promulgation recommended. I. J. Fairchild, Chief, Division of Trade Standards. Promulgated. Lyman J. Briggs, Director, National Bureau of Standards. Promulgation approved. Daniel C. Roper, Secretary of Commerce. II COLORS FOR BATHROOM ACCESSORIES COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS63-38 PURPOSE 1 . Difficulty in securing a satisfactory color match between articles purchased for use in bathrooms, where color harmony is essential to pleasing appearance, has long been a source of inconvenience to pur- chasers. This difficulty is greatest when items made of different materials are produced by different manufacturers. Not only has this inconvenienced purchasers, but it has been a source of trouble and loss to producers and merchants through slow turnover, multiplicity of stock, excessive returns, and obsolescence. -

High Tunnels

High Tunnels Using Low-Cost Technology to Increase Yields, Improve Quality and Extend the Season By Ted Blomgren and Tracy Frisch Produced by Regional Farm and Food Project and Cornell University with funding from the USDA Northeast Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program Distributed by the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture High Tunnels Authors Ted Blomgren Extension Associate, Cornell University Tracy Frisch Founder, Regional Farm and Food Project Contributing Author Steve Moore Farmer, Spring Grove, Pennsylvania Illustrations Naomi Litwin Published by the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture May 2007 This publication is available on-line at www.uvm.edu/sustainableagriculture. Farmers highlighted in this publication can be viewed on the accompanying DVD. It is available from the University of Vermont Center for Sustainable Agriculture, 63 Carrigan Drive, Burlington, VT 05405. The cost per DVD (which includes shipping and handling) is $15 if mailed within the continental U.S. For other areas, please contact the Center at (802) 656-5459 or [email protected] with ordering questions. The High Tunnels project was made possible by a grant from the USDA Northeast Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education program (NE-SARE). Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the United States Department of Agriculture. University of Vermont Extension, Burlington, Vermont. University of Vermont Extension, and U.S. Department of Agriculture, cooperating, offer education and employment to everyone without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or familial status. -

Men's Shirt Sizes (Exclusive of Work Shirts)

' • Naiioaa! Bureau of Standards AU6 13 18« .akeu Iruin Ihb Library. CS135-46 Shirt-Sizes, Men’s (Exclusive of Work Shirts) U. S. Department of Commerce National Bureau of Standards PROMULGATION of COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS135-46 for MEN’S SHIRT SIZES (Exclusive of Work Shirts) On March 2, 1932, a general conference of manufacturers, distribu- tors, and users adopted a recommended commercial standard for men’s shirts (exclusive of work shirts). This recommended commer- cial standard was not officially accepted, but was made available for distribution upon request. The standing committee reviewed subse- quent comment, and prepared a revised draft, which was circulated for written acceptance on October 28, 1938. This draft was accepted by a large portion of the trade. After further review and considera- tion, a sufficient number of signed acceptances were received from manufacturers, distributors, and users to justify promulgation by the United States Department of Commerce, through the National Bureau of Standards. The standard is effective for new production from July 15, 1946. Promulgation recommended. F. W. Reynolds, Acting Chief, Division of Trade Standards. Promulgated. E. U. Condon, Director, National Bureau of Standards. Promulgation approved. Henry A. Wallace, Secretary of Commerce. II MEN^S SHIRT SIZES (Exclusive of Work Shirts) COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS135-46 • PURPOSE 1. The purpose is to provide standard methods of measuring and ( standard minimum measurements for the guidance of producers, || i distributors, and users, in order to eliminate confusion resulting from i a diversity of measurements and methods and to provide a uniform basis for guaranteeing full size. i SCOPE !; 1 2. -

Anniversary of the Thalhimers Lunch Counter Sit-In

TH IN RECOGNITION OF THE 50 ANNIVERSARY OF THE THALHIMERS LUNCH COUNTER SIT-IN Photo courtesy of Richmond Times Dispatch A STUDY GUIDE FOR THE CLASSROOM GRADES 7 – 12 © 2010 CenterStage Foundation Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Standards of Learning 4 Historical Background 6 The Richmond 34 10 Thalhimers Sit-Ins: A Business Owner’s Experience 11 A Word a Day 15 Can Words Convey 19 Bigger Than a Hamburger 21 The Civil Rights Movement (Classroom Clips) 24 Sign of the Times 29 Questioning the Constitution (Classroom Clips) 32 JFKs Civil Rights Address 34 Civil Rights Match Up (vocabulary - grades 7-9) 39 Civil Rights Match Up (vocabulary - grades 10-12) 41 Henry Climbs a Mountain 42 Thoreau on Civil Disobedience 45 I'm Fine Doing Time 61 Hiding Behind the Mask 64 Mural of Emotions 67 Mural of Emotions – Part II: Biographical Sketch 69 A Moment Frozen in Our Minds 71 We Can Change and Overcome 74 In My Own Words 76 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Contributing Authors Dr. Donna Williamson Kim Wasosky Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt Janet Krogman Jon King The lessons in this guide are designed for use in grades 7 – 12, and while some lessons denote specific grades, many of the lessons are designed to be easily adapted to any grade level. All websites have been checked for accuracy and appropriateness for the classroom, however it is strongly recommended that teachers check all websites before posting or otherwise referencing in the classroom. Images were provided through the generous assistance and support of the Valentine Richmond History Center and the Virginia Historical Society. -

James Fishkin

James A. Fishkin Partner Washington, D.C. | 1900 K Street, NW, Washington, DC, United States of America 20006-1110 T +1 202 261 3421 | F +1 202 261 3333 [email protected] Services Antitrust/Competition > Merger Clearance > Merger Litigation: U.S. > James A. Fishkin combines both government and private sector experience within his practice, which focuses on mergers and acquisitions covering a wide range of industries, including supermarket chains and other retailers, consumer and food product manufacturers, internet- based firms, chemical and industrial gas firms, and healthcare firms. He has been a key participant in several of the most significant litigated antitrust cases in the last two decades that have set important precedents, including representing Whole Foods Market, Inc. in FTC v. Whole Foods Market, Inc. and the Federal Trade Commission in FTC v. Staples, Inc. and FTC v. H.J. Heinz Co. Mr. Fishkin has also played key roles in securing unconditional clearances for many high-profile mergers, including the merger of OfficeMax/Office Depot and Monster/HotJobs, and approval for other high-profile mergers after obtaining successful settlements, including the merger of Albertsons/Safeway. He also served as the court-appointed Divestiture Trustee on behalf of the Department of Justice in the Grupo Bimbo/Sara Lee bread merger. Mr. Fishkin has been recognized by Chambers USA, The Best Lawyers in America, The Legal 500 , and Benchmark Litigation for his antitrust work. Chambers USA notes that Mr. Fishkin “impresses sources with his ‘very practical perspective,’ with commentators also describing him as ‘very analytical.’” The Legal 500 states that Mr. -

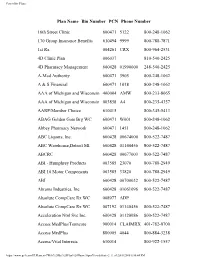

Powerline Plans

Powerline Plans Plan Name Bin Number PCN Phone Number 16th Street Clinic 600471 5122 800-248-1062 170 Group Insurance Benefits 610494 9999 800-788-7871 1st Rx 004261 CRX 800-964-2531 4D Clinic Plan 006037 810-540-2425 4D Pharmacy Management 600428 01990000 248-540-2425 A-Med Authority 600471 3905 800-248-1062 A & S Financial 600471 1018 800-248-1062 AAA of Michigan and Wisconsin 400004 AMW 800-233-8065 AAA of Michigan and Wisconsin 003858 A4 800-235-4357 AARP/Member Choice 610415 800-345-5413 ABAG Golden Gate Brg WC 600471 W001 800-248-1062 Abbey Pharmacy Network 600471 1451 800-248-1062 ABC Liquors, Inc. 600428 00674000 800-522-7487 ABC Warehouse,Detroit MI 600428 01140456 800-522-7487 ABCRC 600428 00677003 800-522-7487 ABI - Humphrey Products 003585 23070 800-788-2949 ABI 10 Motor Components 003585 33820 800-788-2949 ABI 600428 00700032 800-522-7487 Abrams Industries, Inc. 600428 01061096 800-522-7487 Absolute CompCare Rx WC 008977 ADP Absolute CompCare Rx WC 007192 01140456 800-522-7487 Acceleration Ntnl Svc Inc. 600428 01120086 800-522-7487 Access MedPlus/Tenncare 900014 CLAIMRX 401-782-0700 Access MedPlus 880005 4044 800-884-3238 Access/Vital Interests 610014 800-922-1557 https://www.qs1.com/PLPlans.nsf/Web%20By%20Plan%20Name!OpenView&Start=2 (1 of 2)8/8/2006 6:50:44 PM Powerline Plans Accident Fund of Michigan 600428 00700054 800-522-7487 Accubank Mortgage Inc 600428 00672018 800-522-7487 Aclaim 005848 800-422-5246 ACMG Employers Health Plan 400004 ACM 800-233-8065 Acordia Sr Benefits Horizons 600428 00790015 800-522-7487 https://www.qs1.com/PLPlans.nsf/Web%20By%20Plan%20Name!OpenView&Start=2 (2 of 2)8/8/2006 6:50:44 PM Powerline Plans Plan Name Bin Number PCN Phone Number Acordia Sr Benefits Horizons 600428 00790015 800-522-7487 ACT Industries, Inc. -

From Desegregation to Desexigration in Richmond, Virginia, 1954-1973 Leslee Key Virginia Commonwealth University

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by VCU Scholars Compass Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 From Desegregation to Desexigration in Richmond, Virginia, 1954-1973 Leslee Key Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons © The Author Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2603 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©2011 Leslee Key All Rights Reserved From Desegregation to Desexigration in Richmond, Virginia, 1954-1973 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of History at Virginia Commonwealth University By Leslee Key Bachelor’s of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2006 Director: John Kneebone Professor, Department of History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December, 2011 ii Acknowledgements Foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to my advisor Dr. John T. Kneebone for his continued support and indispensable guidance on this endeavor, as well as Dr. Jennifer Fronc who headed my independent study on the Thalhimer boycott in the fall of 2009. I would also like to thank Dr. Timothy Thurber whose endearing sentiments and expertise proved to be of great assistance particularly in times of need. I would like to thank my husband, Eddie, and my children, Brenna (8) and Henry (4), for their patience and support. -

Tiffany Sues As LVMH Scraps $16.2 Billion

P2JW254000-5-A00100-17FFFF5178F ***** THURSDAY,SEPTEMBER 10,2020~VOL. CCLXXVI NO.60 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 27940.47 À 439.58 1.6% NASDAQ 11141.56 À 2.7% STOXX 600 369.65 À 1.6% 10-YR. TREAS. g 6/32 , yield 0.702% OIL $38.05 À $1.29 GOLD $1,944.70 À $11.70 EURO $1.1804 YEN 106.18 Midday, SaN Francisco: Wildfires Cast Eerie Hue Over West TikTok What’s News Parent Is In Talks Business&Finance To Avoid ikTok’sChinese parent, TByteDance, is discuss- ing with the U.S. government U.S. Sale possible arrangementsthat would allowthe video- sharing app to avoid afull ByteDance, Trump sale of itsU.S.operations. A1 administration discuss LVMH said it wasbacking options as deadline for out of its$16.2 billion take- over of Tiffany. TheU.S.jew- unloading assets looms eler said it filed alawsuit in Delaware ChanceryCourt to TikTok’sChinese parent, enforce the agreement. A1, A8 ByteDanceLtd., is discussing An EU privacyregulator with the U.S. government pos- sent Facebook apreliminary sible arrangementsthat would order to suspend datatrans- allow the popular video-shar- fers to the U.S. about itsEU S ing app to avoid a full sale of users in a potentially prec- PRES its U.S. operations, people fa- edent-setting challenge. A1 miliar with the matter said. TED U.S. stocks rebounded CIA SO By Miriam Gottfried, afterathree-session selloff AS in shares of big tech firms, G/ Georgia Wells with the Nasdaq,S&P 500 and Kate Davidson and Dowgaining 2.7%, 2% RISBER ERIC Discussions around such an and 1.6%, respectively. -

Town of Cohasset

, *'W'--jV »;r' vi'54-':>' res 4 COHASSET TOWN REPORT 1940 EDWARD L. STEVENS BORN OCTOBER 26, 1863 DIED SEPTEMBER 30, 1940 Town Accountant 1910 - 1940 Sealer Weights and Measures 1910, 1911, 1912 Auditor 1911 ONE HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL REPORT OF THE BOARD OF SELECTMEN OF THE FINANCIAL AFFAIRS OF THE Town of Cohasset AND THE Report of Other Town Officers For the Year Ending December 31, 1940 Sanderson Brothers North AbIngton, Massachusetts INDEX Assessors, Board of 132 Cohasset Free Public Library 136 Collector of Taxes 117 Fire Department 125 Forest Warden 124 Harbor Master 142 Health Department 130 Highway Surveyor 129 Jury List 118 Moth Superintendent 123 Old Age Assistance, Bureau of 140 Paul Pratt Memorial Library 137 Planning Board 143 Police Department 120 Public Welfare, Board of 135 Registrars, Board of 47 School Department 165 Sealer of Weights and Meiasures 122 Selective Service Registration 122 Selectmen, Board of 135 State Audit of Accounts 144 Balance Sheet, Dec. 31, 1940 161 Town Accountant: Receipts 48 Expenditures 52 Town Clerk: Town Officers and Committees 3 Annual Town Meeting, March 2, 1940 9 Election of Officers, March 9, 1940 17 Vital Statistics 33 Town Treasurer 115 Tree Warden 123 W. P. A 131 Annual Report, Town of Cohasset, 1940 TOWN OFFICERS, 1940-1941 TOWN RECORDS Elected by Ballot Moderator ROBERT B. JAMES Town Clerk WILLIAM H. MORRIS Term expires March, 1941 Selectmen, Assessors and Board of Public Welfare EVERETT W. WHEELWRIGHT Term expires March, 1943 KENDALL T. BATES Term expires March, 1942 DARIUS W. GILBERT, V.S Term expires March, 1941 Treasurer MARY P.