Educational Reform in New Zealand; What Is Going On?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Context of Schooling

Improving School Leadership Activity Education and Training Policy Division http://www.oecd.org/edu/schoolleadership DIRECTORATE FOR EDUCATION IMPROVING SCHOOL LEADERSHIP COUNTRY BACKGROUND REPORT FOR NEW ZEALAND This report was prepared for the New Zealand Ministry of Education for the OECD Activity Improving School Leadership following common guidelines the OECD provided to all countries participating in the activity. Country background reports can be found at www.oecd.org/edu/schoolleadership. New Zealand has granted the OECD permission to include this document on the OECD Internet Home Page. The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the national authority, the OECD or its Member countries. The copyright conditions governing access to information on the OECD Home Page are provided at www.oecd.org/rights 1 CONTENTS Index of tables ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Index of Figures .................................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter One – The national context of schooling ............................................................................... 5 1.1 Economic, social and cultural background ........................................................................ 5 1.2 Broad population trends ..................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Economic and labour market trends -

New Zealand: Full Review 1 New Zealand

Upper Secondary Education in New Zealand: Full Review 1 New Zealand Full Review By Sharon O’Donnell Aim and purpose ■ What is the stated aim and purpose of this stage of education, e.g. linked to entry to higher education, the world of work; a broad aim of personal and societal enrichment etc.? ■ Are these aims and purposes influenced by an overarching national plan for education or do they reflect the influence of international organisations such as the OECD? The education system those in hardship, find a out what the Government in New Zealand aims to better future; to enable intends to do during the create better life choices everyone to succeed; and period 2016-2020 to achieve and outcomes for New to create the foundation these aims. Of particular Zealanders; to equip for a flourishing society note in terms of senior them to thrive in the and a strong economy. secondary schooling (for rapidly developing global The four-year education 15/16- to 18-year-olds) are the environment; to help plan Ambitious for New ambitions to: young people, especially Zealand (MoE, 2016a) sets ■ improve student-centred pathways ■ provide better ‘tailoring’ so that educational services are responsive to the diverse needs of every student in the context of the future economy ■ raise the aspirations of all children and students ■ offer better and more relevant pathways through the education system and beyond into the workplace and society ■ strengthen inclusion. The plan links to the Tertiary and numeracy; and The long-term aim is to Education Strategy 2014- -

Samoan Research Methodology

VolumePacific-Asian 23 | Number Education 21 | 2011 Pacific-Asian Education The Journal of the Pacific Circle Consortium for Education Volume 23, Number 2, 2011 SPECIAL ISSUE Inside (and around) the Pacific Circle: Educational Places, Spaces and Relationships SPECIAL ISSUE EDITORS Eve Coxon The University of Auckland, New Zealand Airini The University of Auckland, New Zealand SPECIAL ISSUE EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Elizabeth Rata The University of Auckland, New Zealand Diane Mara The University of Auckland, New Zealand Carol Mutch The University of Auckland, New Zealand EDITOR Elizabeth Rata, School of Critical Studies in Education, Faculty of Education, The University of Auckland, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] EXECUTIVE EDITORS Airini, The University of Auckland, New Zealand Alexis Siteine, The University of Auckland, New Zealand CONSULTING EDITOR Michael Young, Institute of Education, University of London EDITORIAL BOARD Kerry Kennedy, The Hong Kong Institute of Education, Hong Kong Meesook Kim, Korean Educational Development Institute, South Korea Carol Mutch, Education Review Office, New Zealand Gerald Fry, University of Minnesota, USA Christine Halse, University of Western Sydney, Australia Gary McLean, Texas A & M University, USA Leesa Wheelahan, University of Melbourne, Australia Rob Strathdee, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand Xiaoyu Chen, Peking University, P. R. China Saya Shiraishi, The University of Tokyo, Japan Richard Tinning, University of Queensland, Australia ISSN 1019-8725 Pacific Circle Consortium for Education Publication design and layout: Halcyon Design Ltd, www.halcyondesign.co.nz Published by Pacific Circle Consortium for Education http://pacificcircleconsortium.org/PAEJournal.html Pacific-Asian Education Volume 23, Number 2, 2011 CONTENTS Editorial Eve Coxon 5 Articles Tala Mai Fafo: (Re)Learning from the voices of Pacific women 11 Tanya Wendt Samu Professional development in the Cook Islands: Confronting and challenging 23 Cook Islands early childhood teachers’ understandings of play. -

Factsheet: International Education in New Zealand • in 2017 125,392

Factsheet: International Education in New Zealand • In 2017 125,392 international students studied in New Zealand, contributing to a thriving and globally connected New Zealand. • International education is New Zealand’s fourth largest export earner valued at $5.1 billion. It makes an important contribution to our national and regional economies. • This $5.1 billion was comprised of $4.8 billion from international students visiting New Zealand and $0.3 billion from education and training goods and services delivered offshore. • A larger share of economic value was attributed regionally in 2017 than in previous years – largely due to a small decrease in the number of students studying in Auckland. Please note, however, that international education continues to be very significant for Auckland and its economic contribution remained strong at $2.76b in 2017, and just over half (56%) of the national figure (in line with a value over volume focus and sustainable growth). The next largest economic contributions were received in university regions, that is, by Canterbury (10%), Wellington (9%) and Waikato and Otago (both 6%). Fourteen percent of the total economic contribution in 2017 was spent outside the regions where students were based (e.g. while living in one region students are busy domestic tourists; while living in one region students also consume food grown in other regions). • Just under 50,000 jobs are supported by the international education sector. This is made up of 47,500 jobs onshore connected to visiting students, and a further 2,141 jobs (973 in New Zealand and 1,168 offshore) from offshore activity in 2017. -

NZ Sociology 28:3

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AUT Scholarly Commons Crothers Appendix: The New Zealand Literature on Social Class/Inequality Charles Crothers A broad account of the New Zealand class system can be readily assembled from popularly-available sources such as the item in the official New Zealand online Encyclopaedia Te Ara or the Wikipedia entry, together with common knowledge. Having provided a sketch, this appendix then goes on to provide a brief overview and then listing of a bibliography on Social Class/Inequality in New Zealand. Traditional Māori society was strongly based on rank, which derived from ancestry (whakapapa). There were three classes – chiefs, commoners and slaves - with very limited mobility between them. Chiefs were almost invariably descended from other chiefs, although those in line to take up a chieftainship would be bypassed in favour of a younger brother if they did not show aptitude. In some tribes exceptional women could emerge to take on leadership roles. Prisoners of war were usually enslaved with no rights and often a low life expectancy. However, children of slaves were free members of the tribe. Contemporary Māori society is far less hierarchical and there are a variety of routes to prominence. European settlement of New Zealand came with a ready-made class structure imposed by the division between cabin and steerage passengers with the former mainly constituting middle class with a sprinkling of upper class ‘settlers’. This shipboard class division was reinforced by the Wakefield settlement system which endeavoured to reproduce a cross-section of UK society in the colony, with the mechanism that capital was needed by the middle/upper class to provide the frame in which the working class voyagers (they were only retrospectively entitled to be termed ‘settlers’) could be put to work. -

Tomorrow's Schools 20 Years On

Thinking research Tomorrow’s Schools 20 years on... Edited by John Langley Tomorrow’s Schools 20 years on... Edited by John Langley Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 3 CHAPTER 1 Dr. John Langley 5 Introduction CHAPTER 2 Harvey McQueen 19 Towards a covenant CHAPTER 3 Wyatt Creech 29 Twenty years on CHAPTER 4 Howard Fancy 39 Re-engineering the shifts in the system CHAPTER 5 Elizabeth Eppel 51 Curriculum, teaching and learning: A celebratory review of a very complex and evolving landscape CHAPTER 6 Barbara Disley 63 Can we dare to think of a world without special education? CHAPTER 7 Terry Bates 79 National mission or mission improbable? CHAPTER 8 Brian Annan 91 Schooling improvement since Tomorrow’s Schools CHAPTER 9 Margaret Bendall 105 A leadership perspective Published by Cognition Institute, 2009. ISBN: 978-0-473-15955-9 CHAPTER 10 John Hattie 121 ©Cognition Institute, 2009. Tomorrow’s Schools - yesterday’s news: The quest for a new metaphor All rights reserved. No portion of this publication, printed or CHAPTER 11 Cathy Wylie 135 electronic, may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without Getting more from school self-management the express written consent of the publisher. For more information, email [email protected] CHAPTER 12 Phil Coogan and Derek Wenmoth 149 www.cognitioninstitute.org Tomorrow’s Web for our future learning 1 Acknowledgements The Cognition Education Research Trust (CERT) has a growing network of people and organisations participating in and contributing to the achievement of our philanthropic purposes. There are many who have enabled and contributed to this first thought leader publication on ‘Tomorrow’s Schools Twenty Years On’. -

Primary and Secondary School Science Education in New Zealand (Aotearoa) – Policies and Practices for a Better Future

Primary and Secondary School Science Education in New Zealand (Aotearoa) – Policies and Practices for a Better Future Prepared by David M Vannier, PhD With funding from the sponsors of the Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy August 2012 Established by the Level 8, 120 Featherston Street Telephone +64 4 472 2065 New Zealand government in 1995 PO Box 3465 Facsimile +64 4 499 5364 to facilitate public policy dialogue Wellington 6140 E-mail [email protected] between New Zealand and New Zealand www.fulbright.org.nz the United States of America © David M Vannier 2012 Published by Fulbright New Zealand, August 2012 The opinions and views expressed in this paper are the personal views of the author and do not represent in whole or part the opinions of Fulbright New Zealand or any New Zealand government agency. ISBN 978-1-877502-34-7 (print) ISBN 978-1-877502-35-4 (PDF) Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy Established by the New Zealand Government in 1995 to reinforce links between New Zealand and the US, Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy provide the opportunity for outstanding mid-career professionals from the United States of America to gain firsthand knowledge of public policy in New Zealand, including economic, social and political reforms and management of the government sector. The Ian Axford (New Zealand) Fellowships in Public Policy were named in honour of Sir Ian Axford, an eminent New Zealand astrophysicist and space scientist who served as patron of the fellowship programme until his death in March 2010. -

11. How 'Specialese' Maintains a Dual Education System in Aotearoa New

11. HOW ‘SPECIALESE’ MAINTAINS A DUAL EDUCATION SYSTEM IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND BERNADETTE MACARTNEY INTRODUCTION I found it difficult to settle on a way of approaching and understanding my own and other families’ experiences of education through our eyes and those of our children, grandchildren, siblings, cousins and other family members. I have been writing, studying, researching, observing, thinking, teaching, advocating and talking so much and often not getting very far, since our daughter Maggie Rose was ‘diagnosed’ 17 years ago that it’s hard not to get tired of saying the same things. I know I’m not the only parent who has to fight similar battles over and over. Unfortunately I hear people whose adult children are now in their 30s and 40s saying the same things about their experiences of being excluded from and within education. National New Zealand organisations such as People First, IHC Advocacy, CCS Disability Action, Inclusive Education Action Group and the Disabled Persons Assembly speak as and on behalf of disabled people. Disabled people, their families and allies are providing the critique that our education system needs to inform its transformation. For some years before I moved to Wellington, I was operating under the (false) assumption that research conclusions, disabled people’s voices, the influence and leadership of the human rights discourse reflected in the Education and Human Rights legislation, United Nations Conventions, the New Zealand Disability Strategy (Ministry of Health, 2001), early childhood and school education curriculum documents and resources, shared a consensus view about inclusive education. I anticipated that we would have dismantled our dual special-regular education system and replaced it with a fully inclusive one by now. -

Māori Equity in New Zealand's Polytechnics

Māori Equity in New Zealand’s Polytechnics by Khalid Bakhshov A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Auckland University of Technology 2020 Acknowledgements Without the support of colleagues, friends and family it is doubtful that I would have ever reached the end of this doctoral thesis. But, firstly, I must start my thanks with my main supervisor, Dr Georgina Stewart. She patiently guided me through this journey, encouraging me to fully explore my philosophical instincts. In supervision, session after session, she helped me develop a voice in the writing process that was my own. Her constant engagement with philosophy and tireless pursuit of expression led me through challenging self-scrutiny that a thesis inevitably demands. The patient structured support was invaluable to me. I hope she enjoyed the challenge as much as I did. I would also like to express my gratitude to Professor Nesta Devine for her wealth of experience and encouragement from a distance in supporting the supervision process. I would also like to acknowledge the initial support given to me through the University of Auckland, where I started my thesis. Thanks to all my friends in Whangarei, who all supported and encouraged me, as friends do, in pursuing the topic. They gave me, in their very different ways, their insider accounts that spurred me to undertake this study. Thank you, Hamish, Danny and George. At a personal level I will always be grateful for the support of my partner Johan Carvill and her family. Johan has provided me with personal support all the way through the process, putting up with ups and downs and in my final year financially supporting us. -

Is There a Civil Religious Tradition in New Zealand

The Insubstantial Pageant: is there a civil religious tradition in New Zealand? A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies in the University of Canterbury by Mark Pickering ~ University of Canterbury 1985 CONTENTS b Chapter Page I (~, Abstract Preface I. Introduction l Plato p.2 Rousseau p.3 Bellah pp.3-5 American discussion on civil religion pp.S-8 New Zealand discussion on civil religion pp.S-12 Terms and scope of study pp.l2-14 II. Evidence 14 Speeches pp.lS-25 The Political Arena pp.25-32 Norman Kirk pp.32-40 Waitangi or New Zealand Day pp.40-46 Anzac Day pp.46-56 Other New Zealand State Rituals pp.56-61 Summary of Chapter II pp.6l-62 III. Discussion 63 Is there a civil religion in New Zealand? pp.64-71 Why has civil religion emerged as a concept? pp.71-73 What might be the effects of adopting the concept of civil religion? pp.73-8l Summary to Chapter III pp.82-83 IV. Conclusion 84 Acknowledgements 88 References 89 Appendix I 94 Appendix II 95 2 3 FEB 2000 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the concept of 'civil religion' and whether it is applicable to some aspects of New zealand society. The origin, development and criticism of the concept is discussed, drawing on such scholars as Robert Bellah and John F. Wilson in the United States, and on recent New Zealand commentators. Using material such as Anzac Day and Waitangi Day commemorations, Governor-Generals' speeches, observance of Dominion Day and Empire Day, prayers in Parliament, the role of Norman Kirk, and other related phenomena, the thesis considers whether this 'evidence' substantiates the existence of a civil religion. -

Friend Or Ally? a Question for New Zealand

.......... , ---~ MeN AIR PAPERS NUMBER T\\ ELVE FRIEND OR ALLY? A QUESTION FOR NEW ZEALAND By EWAN JAMIESON THE INSTI FUTE FOR NATIONAL SI'R-~TEGIC STUDIES ! I :. ' 71. " " :~..? ~i ~ '" ,.Y:: ;,i:,.i:".. :..,-~.~......... ,,i-:i:~: .~,.:iI- " yT.. -.~ .. ' , " : , , ~'~." ~ ,?/ .... ',~.'.'.~ ..~'. ~. ~ ,. " ~:S~(::!?- ~,i~ '. ? ~ .5" .~.: -~:!~ ~:,:i.. :.~ ".: :~" ;: ~:~"~',~ ~" '" i .'.i::.. , i ::: .',~ :: .... ,- " . ".:' i:!i"~;~ :~;:'! .,"L': ;..~'~ ',.,~'i:..~,~'"~,~: ;":,:.;;, ','" ;.: i',: ''~ .~,,- ~.:.~i ~ . '~'">.'.. :: "" ,-'. ~:.." ;';, :.~';';-;~.,.";'."" .7 ,'~'!~':"~ '?'""" "~ ': " '.-."i.:2: i!;,'i ,~.~,~I~out ;popular: ~fo.rmatwn~ .o~~'t,he~,,:. "~.. " ,m/e..a~ tg:,the~6w.erw!~chi~no.wtetl~e.~gi..~e~ ;~i:~.::! ~ :: :~...i.. 5~', '+~ :: ..., .,. "'" .... " ",'.. : ~'. ,;. ". ~.~.~'.:~.'-? "-'< :! :.'~ : :,. '~ ', ;'~ : :~;.':':/.:- "i ; - :~:~!II::::,:IL:.~JmaiegMad}~)~:ib;:, ,?T,-. B~;'...-::', .:., ,.:~ .~ 'z • ,. :~.'..." , ,~,:, "~, v : ", :, -:.-'": ., ,5 ~..:. :~i,~' ',: ""... - )" . ,;'~'.i "/:~'-!"'-.i' z ~ ".. "', " 51"c, ' ~. ;'~.'.i:.-. ::,,;~:',... ~. " • " ' '. ' ".' ,This :iis .aipul~ ~'i~gtin~e ..fdi;:Na~i~real..Sfi'~te~ie.'Studi'~ ~It ;is, :not.i! -, - .... +~l~ase,~ad.~ p,g, ,,.- .~, . • ,,. .... .;. ...~,. ...... ,._ ,,. .~ .... ~;-, :'-. ,,~7 ~ ' .~.: .... .,~,~.:U7 ,L,: :.~: .! ~ :..!:.i.i.:~i :. : ':'::: : ',,-..-'i? -~ .i~ .;,.~.,;: ~v~i- ;. ~, ~;. ' ~ ,::~%~.:~.. : ..., .... .... -, ........ ....... 1'-.~ ~:-~...%, ;, .i-,i; .:.~,:- . eommenaati6'r~:~xpregseff:or ;ii~iplie'd.:;~ifl~in.:iat~ -:: -

Spring Fling

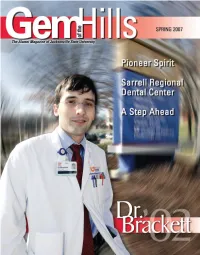

insurance administrator to human resources of the manager, all providing free services to GemThe Alumni Magazine of JacksonvilleHills State University deserving children with Medicaid or ALL- Vol. XIII, No. 2 KIDS insurance. Additional details about the JSU President dreams the center has and the ones they fulfill William A. Meehan, Ed.D., ’72/’76 are located on page 12. Vice President for Institutional Many patients at Erlanger Hospital in Advancement Chattanooga, Tenn. are also benefiting from Joseph A. Serviss, ’69/’75 a JSU alumnus thanks to the skills of Dr. Alumni Association President Stephen Brackett. The feature story on page Sarah Ballard,’69/’75/’82 15 tracks Brackett’s life from his decision to Director of Alumni Affairs and Editor attend JSU to his current life as a hospital Kaci Ogle, ’95/’04 resident. Art Director With a “STEP” in the right direction, Mary Smith, ’93 JSU’s College of Nursing and Health Sciences Staff Artists Dr. William A. Meehan, President Strategic Teaching for Enhanced Professional Erin Hill, ’01/’05 Preparation Program (page 18) is succeeding Rusty Hill in helping licensed RNs obtain higher Graham Lewis Dear Alumni, education goals while still fulfilling personal Copyeditor/Proofreader and occupational duties. Sybil Roark tells Gem Erin Chupp, ’05 In this issue, JSU alumni in healthcare how she returned to JSU for her master’s in Gloria Horton professions and the College of Nursing and nursing while working and raising children. In Staff Writers Health Sciences are highlighted as one of this article she explains how she searched for “a Al Harris, ’81/’91 the outstanding sectors of Jacksonville State quality education” and why JSU had “the best Anne Muriithi University.