Origins & Excursions in Pigeon Genetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on the Nesting Behaviour of Yellow Footed Green Pigeon Treron Phoenicoptera at Jeypore Reserve the Dilli Rivers Form a Part of the Reserve Boundary

JoTT SHORT COMMUNI C ATION 4(3): 2470–2475 Notes on the nesting behaviour of Yellow-footed Green Pigeon Treron phoenicoptera (Columbidae) at Jeypore Reserve Forest, Assam, India O.S. Devi 1 & P.K. Saikia 2 1 Research Scholar, 2 Associate Professor, Animal Ecology and Wildlife Biology Lab., Department of Zoology, Gauhati University, Guwahati 781014, Assam, India Email: 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: We surveyed five nesting colonies of Yellow-footed the sole vector for seed dispersal of certain tree species Green Pigeon at Jeypore Reserve forest to study their nesting behaviour during two breeding seasons in 2008 and 2009. We (Meehan et al. 2005). Data on their ecological and observed the birds in five closely-watched nests and studied their biological aspects is deficient as very few studies have behaviour starting from pair formation till hatching of squabs. Pair formation generally starts from the month of April followed by been conducted on the Columbidae group as a whole nest building and incubation, with ultimately, hatching of squabs (Wiley & Wiley 1979; Burger et al. 1989; Steadman during May, which continues up to the month of June. Both 1997; Bancroft et al. 2000; Strong & Johnson 2001; sexes share the duty of nest building and incubation. Breeding pairs took four shifting intervals during incubation period at a time Walker 2007). The Yellow-footed Green Pigeon is interval of about 2–5 hrs in each shift. Incubation period ranges widely distributed throughout the Indian subcontinent between 20–23 days. and is a commonly sighted frugivorous bird in the Keywords: Behaviour, Columbidae, incubation, Jeypore Reserve tropical forests of eastern Himalaya (Ali & Ripley Forest, squabs, Yellow-footed Green Pigeon. -

Japanese Green Pigeon Aobato (Jpn) Treron Sieboldii 142°13'E)

Bird Research News Vol.8 No.9 2011.9.28. Japanese Green Pigeon Aobato (Jpn) Treron sieboldii 142°13'E). This species ranges to the northernmost region among Morphology and classification the genus Treron (Nakamura 1980). The subspecies T. s. sieboldii is assumed to be endemic to Japan (Kiyosu 1978, Gibbs 2001, Classification: Columbiformes Columbidae Komatan 2004a). Total length: 315-348mm Wing length: ♂ 183-196mm ♀ 177-187mm ♂ Juv. 172-186mm Habitat: Tail length: ♂ 109-133mm ♀ 103-123mm ♂ Juv. 100-105mm Japanese Green Pigeons are forest-dwellers from hills to moun- Culmen length: Ad. 18-21mm ♂ Juv. 20mm tains. They rarely come123456789101112月 out to an open place, but they have a habit 繁殖期 Tarsus length: Ad. 24-28mm ♂ Juv. 20-27mm of visiting a coastal area(つがい形成〜家族期) in a flock to drink換羽期 seawater 非繁殖期 from early Weight: Ad. 217-300g summer to autumn. They spend most of the breeding period in broad-leaved deciduous forests south of Honshu, but they are less Total length after Enomoto (1941), other measurements of adults after Kiyosu (1978), abundant in Hokkaido, northern Japan (Fujimaki 1999). and those of juveniles (age approximately 1.5-2 months) after Komatan (2004b). Appearance: Life history The Japanese Green Pigeons are roughly green all over with some 123456789101112 sexual dimorphism in plumage coloration. They have pink feet and courting breeding period non-breeding soft light blue bills. The iris is two-toned with the outer red ring period period and blue inner ring (Photo 1). Males have reddish purple patch on Breeding system: the small and middle wing coverts, greenish brown patch on the Japanese Green Pigeons breed from mid-May to mid-September in greater wing coverts and grayish green long and broad shaft-stripes the Tanzawa mountains, Kanagawa Pref., central Japan. -

The Collection of Birds from São Tomé and Príncipe at the Instituto De Investigação Científica Tropical of the University of Lisbon (Portugal)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 600:The 155–167 collection (2016) of birds from São Tomé and Príncipe at the Instituto de Investigação... 155 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.600.7899 DATA PAPER http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The collection of birds from São Tomé and Príncipe at the Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical of the University of Lisbon (Portugal) Miguel Monteiro1,2, Luís Reino1,2,3, Martim Melo1,4, Pedro Beja1,2, Cristiane Bastos-Silveira5, Manuela Ramos7, Diana Rodrigues5, Isabel Queirós Neves5,6, Susana Consciência8, Rui Figueira1,2 1 CIBIO/InBIO-Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal 2 CEABN/InBio, Centro de Ecologia Aplicada “Professor Baeta Neves”, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisboa, Portugal 3 CIBIO/InBIO-Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade de Évora, 7004-516 Évora, Portugal 4 Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701X, South Africas 5 Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência, Universidade de Lisboa, Rua da Escola Politécnica 56, 1250-102 Lisboa, Portugal 6 CESAM-Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies, Universidade de Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal 7 MARE-FCUL, DOP/UAç - Departamento Oceanografia e Pescas, Univ. Açores, Rua Prof. Dr. Fre- derico Machado, 9901-862 Horta, Portugal 8 Estrada de Mem Martins n251 1ºDto, 2725-391 Mem Martins, Sintra, Portugal Corresponding author: Rui Figueira ([email protected]) Academic editor: G. Sangster | Received 29 January 2015 | Accepted 2 June 2016 | Published 22 June 2016 http://zoobank.org/68209E54-00D0-4EFA-B095-AB7D346ACD8E Citation: Monteiro M, Reino L, Melo M, Beja P, Bastos-Silveira C, Ramos M, Rodrigues D, Neves IQ, Consciência S, Figueira R (2016) The collection of birds from São Tomé and Príncipe at the Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical of the University of Lisbon (Portugal). -

Chordate Sections

Utinomi's Bibliographica Micronesica: Chordate Sections HARVEY I. FISHER1 A COpy OF Bibliographica Micronesica / branches of science it would be inadvisable Scientiae Nattlraliset Cultus, by Dr. Huzio to start a study without some knowledge of Utinomi, became temporarily· available in the work carried on by Japanese scientists the Territory of Hawaii late in the summer in the mandated islands. of 1946. This bibliography of 208 pages Because of the above facts it seems desir was published in 1944 by the Hokuryiikan able to publish immediately all the titles Publishing Company in Tokyo. A negative given by Utino.(l1i, and to add translations microfilm was made by the University of of the titles and publications cited in the Hawaii Library, and later certain sections Japanese language. The present paper in were enlarged and printed photograph cludes only those sections dealing with chor ically. date animals, and constitutes pages 24 to 43 An interest in the vertebrate animals of of the original publication, in addition to the Micronesia, especially those of Yap, led me translated Preface and Explanatory Notes. to have certain Japanese titles translated for The list of titles is of course not exhaus personal use. It soon became evident that tive, but it is not the purpose of this pub although the bibliography was not com lication to. add titles to Utinomi's list. A plete, it did include many significant titles complete bibliography of the chordates in that had previously been overlooked by Micronesia would take years of preparation workers in vertebrate zoology. and research in many libraries. The imme This bibliography has great interest at the diate usefulness of the bibliography in its present time. -

Pigeon Barbara Allen

Pigeon Barbara Allen Animal series Pigeon Animal Series editor: Jonathan Burt Already published Crow Fox Spider Boria Sax Martin Wallen Katja and Sergiusz Michalski Ant Fly Pig Charlotte Sleigh Steven Connor Brett Mizelle Tortoise Cat Camel Peter Young Katharine M. Rogers Robert Irwin Cockroach Peacock Chicken Marion Copeland Christine E. Jackson Annie Potts Dog Cow Wolf Susan McHugh Hannah Velten Garry Marvin Oyster Duck Ape Rebecca Stott Victoria de Rijke John Sorenson Bear Shark Butterfly Robert E. Bieder Dean Crawford Matthew Brower Bee Swan Sheep Claire Preston Peter Young Philip Armstrong Rat Rhinoceros Giraffe Jonathan Burt Kelly Enright Mark Williams Snake Horse Eagle Drake Stutesman Elaine Walker Ron Broglio Falcon Elephant Jellyfish Helen Macdonald Daniel Wylie Eva Hayward Whale Moose Penguin Joe Roman Kevin Jackson Stephen Martin Parrot Eel Owl Paul Carter Richard Schweid Desmond Morris Tiger Susie Green Forthcoming Salmon Hare Peter Coates Simon Carnell Pigeon Barbara Allen reaktion books For David, for Rhys (thank you for bringing home an injured squab during the writing of this book), and for my feathered friends, named (Bacardi, Chagall, Bert, Celeste, Olympia and Splash) and unnamed; you are truly magnificent! Published by reaktion books ltd 33 Great Sutton Street London ec1v 0dx, uk www.reaktionbooks.co.uk First published 2009 Copyright © Barbara Allen 2009 This book has been published with the assistance of the Australian Academy of the Humanities All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. -

The Spotted Green Pigeon Caloenas Maculata

Hein van Grouw 291 Bull. B.O.C. 2014 134(4) The Spoted Green Pigeon Caloenas maculata: as dead as a Dodo, but what else do we know about it? by Hein van Grouw Received 31 July 2014 Summary.—Described in 1783 and since then re-examined by many notable ornithologists, the single specimen known as the ‘Spoted Green Pigeon’ Caloenas maculata in the collections of the World Museum, Liverpool, has always been a mystery. No-one has ever doubted that it is a pigeon, and many researchers were convinced it was a distinct species. Although its taxonomic status remained unclear, it was ofcially declared extinct by BirdLife International in early 2008. Recent DNA analysis has now revealed that Spoted Green Pigeon can indeed be considered a distinct species within the extended Dodo Raphus cucullatus clade of morphologically very diverse pigeon species. Most members of this clade exhibit terrestrial or semi-terrestrial habits. Further morphological research into this unique specimen, initiated by the World Museum, demonstrates that Spoted Green Pigeon, in contrast to its fellow clade members, may have possessed strongly arboreal habits. The Spoted Green Pigeon Caloenas maculata, represented by a single specimen held in the scientifc collections of the World Museum, Liverpool, has always bafed ornithologists. Although its provenance is unknown, the confusion has mainly centred on whether it is a valid species; that the specimen is a pigeon has never been questioned. Because of its green-glossed plumage and slightly elongated hackles, it is usually assumed to be allied to Nicobar Pigeon C. nicobarica, although they share few other morphological features. -

Caloenas Nicobarica), the Last Living Relative of Dodo Bird

International Journal of Agricultural Technology 2021 Vol. 17(2):713-726 Available online http://www.ijat-aatsea.com ISSN 2630-0192 (Online) A non-invasive molecular genetic technique for sex identification of Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica), the last living relative of Dodo bird Seritrakul, P. and Laosutthipong, C. Faculty of Animal Sciences and Agricultural Technology, Silpakorn University, Phetchaburi IT campus, Sampraya, Cha-am, Phetchaburi 76120, Thailand. Seritrakul, P. and Laosutthipong, C. (2021). A non-invasive molecular genetic technique for sex identification of Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica), the last living relative of Dodo bird. International Journal of Agricultural Technology 17(2):713-726. Abstract Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica) is the last surviving member of the genus Caloenas and the closest living relative of the extinct Dodo bird. It is classified as a near- threatened species that is illegally trapped for consumption, extraction of decorative gizzard stones, and as pets due to its size and attractive appearance. Captive breeding is essential for conservation effort and potential future commercialization of Nicobar pigeon. However, it is difficult due to the sexually-monomorphic and monogamous nature of the species. A non- invasive PCR-based technique for sex identification of Nicobar pigeon was presented here, which provided a fast and reliable method that achieves accurate results within 8 hours. Using feather samples individually obtained from captive Nicobar pigeons, results were also compared between molecular sexing method against traditional morphology-based sexing methods by vent and hackle length. However, no correlation was found between the molecular and morphological methods. Additionally, bioinformatic analysis of the amplified DNA sequence was performed for Nicobar pigeon, which showed its phylogenetic relationship with other members of the pigeon and dove family (Columbidae). -

Breeding Status of Wild Doves in Bangladesh

International Journal of Research Studies in Zoology Volume 6, Issue 1, 2020, PP 1-4 ISSN No. 2454-941X DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-941X.0601001 www.arcjournals.org Breeding Status of Wild Doves in Bangladesh Ashraful Kabir* Department of Biology, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, Nilphamari, Bangladesh *Corresponding Author: Ashraful Kabir, Department of Biology, Saidpur Cantonment Public College, Nilphamari, Bangladesh Out of 17 species of wild doves in Bangladesh their incubation period ranges from 12-20 and fledging 12-27 days. Within these 14 species were in Least Concern (LC), 2 Data Deficit (DD), and 1 Critically Endangered (CR). Among these maximum numbers were found in the genus Treron (6) then Streptopelia (4), Columba and Ducula each 2, and Spilopelia and Macropygia 1. Observed doves were bred mostly all the year round. For hunting or pet purpose people sometime catch them and rear in cage and ultimately birds’die. For strong ‘Wildlife Act’ now doves of Bangladesh are living well and are increasing everywhere in nature as well. On the basis of evolutionary sequences pigeons/doves have great significance. It has lots of connecting links which are very important for the study of evolution. In fancy pigeons, their tumbling behaviour is an exceptional and peculiar characteristic which came through mutation then modified by millions of thousands selective breeding. From the history, we have found that pigeon/dove keeping was an ancient hobby of people. Large-sized birds are called pigeon and small are dove; but this is not true always. For message sending, pigeons had great commitment in the world. -

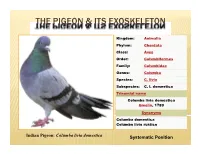

The Pigeon & Its Exoskeleton

THE PIGEON & ITS EXOSKELETON Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Order: Columbiformes Family: Columbidae Genus: Columba Species: C. livia Subspecies: C. l. domestica Trinomial name Columba livia domestica Gmelin, 1789 Synonyms Columba domestica Columba livia rustica Indian Pigeon: Columba livia domestica Systematic Position GENERAL FEATURES OF BIRDS (AVES) General Characteristics of Aves •warm blooded animals. •no skin glands except uropigial glands. •feathers as exoskeleton. •fore limbs are modified into wings. •hind limbs are adapted tfor walking. •the bones are spongy. •lower jaw contain 5 or 6 bones. •double headed vertebral ribs. •The ankle joint is inter tarsal. •lungs are non ditensible. •Syrinx produce the voice. •no vocal cord in lyrinx. •heart is 4-chambered. •R.B.C. are nucleated. •sexes are separate. •oviparous. •skull is monocondylic. COLUMBA IN FLIGHT GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO PIGEON COMMON NAME: Kabutar in Hindi and Rock Pigeon in English, Paira in Bengali. DISTRIBUTION: found in India, Pakistan, Ceylon and Burma. FOOD: cereals, pulses, ground nuts, etc. IDENTIFYING CHARACTERS: • Body length- about 34 cm or more. • Body color-slaty-grey, metallic green and purple. • Neck- magenta in color. • Wings- two dark bars on wings. • Tail- a band is present across the end of the tail. • The bird is so familiar to human. • The nest is made up of twigs and straw. SPOTTED DOVE: A CLOSE RELATIVE OF PIGEON The spotted dove (Spilopelia chinensis) is a small and somewhat long-tailed pigeon which is a common resident breeding bird across its native range on theIndian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It is sometimes also called the mountain dove, pearl-necked dove or lace-necked dove. -

Timor Green-Pigeon (Treron Psittaceus) - Birdlife Species Factsheet Page 1 of 4

Timor Green-pigeon (Treron psittaceus) - BirdLife species factsheet Page 1 of 4 Search | Tips Go gfedc Data Zone only Home > Data Zone > Home Timor Green-pigeon - BirdLife Species Factsheet show additional data In this Section About BirdLife Search for Species BirdLife Partnership Species Information Regional Work EN Timor Green-pigeon Treron psittaceus Terms & Definitions News Taxonomy References A-L Global Programmes 2009 IUCN Red List Category (as evaluated by BirdLife References M-Z Action International - the official Red List Authority for birds for IUCN): Endangered Publications See Also Help BirdLife Justification The population of this species is suspected to be declining very Philatelic praise for Pacific's Data Zone parrots and rapidly, concurrent with the rapid reduction in its lowland forest habitat. As a First photos of rare dove Search Species result, it is classified as Endangered. Search Sites New sightings of a small island specialist Search EBAs What's New (2009) State of Birds Family/Sub-family Columbidae Species facts & figures Species name author (Temminck, 1808) The BirdLife Preventing Global Species Programme Extinctions Programme Taxonomic source(s) Sibley and Monroe (1990, 1993) The BirdLife checklist of the Donate to this birds of the world with groundbreaking initiative Synonyms Treron psittacea Sibley and Monroe (1990, 1993), Treron conservation status and so that together we can psittacea BirdLife International (2004), Treron psittacea BirdLife International taxonomic sources. Version 2 turn the tide on bird [.zip, 1.5mb] extinctions. (2000), Treron psittacea Collar et al. (1994), Treron psittacea Collar and Related Sites Andrew (1988) Lynx Edicions Taxonomic note Gender agreement of species name follows David and Threatened Birds of the Gosselin (2002b). -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Malaysia

Avibase Page 1of 23 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Malaysia 2 Number of species: 799 3 Number of endemics: 14 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of introduced species: 17 6 Date last reviewed: 2020-03-19 7 8 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Malaysia. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=my [23/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Northeast India: Mega Birds of the HIMALAYAS

Northeast India: Mega Birds of the HIMALAYAS A Tropical Birding Custom Tour May 9-28, 2019 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos by Ken Behrens TOUR SUMMARY Northeast India, specifically the states of Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, offer a dazzling array of habitats, from Brahmaputra River grasslands, to lush hill rainforests, to montane forest, all the way up to Alpine habitats above treeline. These habitats support a huge array of birds, including some of the best-looking and most sought-after of Asian birds. It’s no exaggeration to say that this area of the eastern Himalayas offers the best montane birding in all of Asia. This custom tour was build around a short list of target birds. Chief among these were Slender-billed Vulture, Green (see photo above) and Purple Cochoas, and Beautiful Nuthatch. It took a lot of work, but we enjoyed excellent, lengthy views of all of these targets. In general, hard work with great rewards was a theme of this trip. There were a couple dozen other targets, the vast majority of which we found as we put in the time in the field. Birding in this part of the world is never easy. Many of the birds are shy and seem to exist in low densities. But this very fact makes encountering them all the more satisfying! In the Assam plains, we visited two excellent national parks: Kaziranga and Manas. These parks are famous among general tourists as sites for big mammals, especially a large population Northeast India May 9-28, 2019 of Indian Rhino. Among birders, they’re more famous for holding scarce grassland birds like Black- breasted Parrotbill, Indian Grassbird, Jerdon’s and Slender-billed Babblers, Pale-footed Bush Warbler, and Yellow or Finn’s Weaver, all of which we saw.