Labialization and Palatalization in Judeo-Spanish Phonology*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phonological Domains Within Blackfoot Towards a Family-Wide Comparison

Phonological domains within Blackfoot Towards a family-wide comparison Natalie Weber 52nd algonquian conference yale university October 23, 2020 Outline 1. Background 2. Two phonological domains in Blackfoot verbs 3. Preverbs are not a separate phonological domain 4. Parametric variation 2 / 59 Background 3 / 59 Consonant inventory Labial Coronal Dorsal Glottal Stops p pː t tː k kː ʔ <’> Assibilants ts tːs ks Pre-assibilants ˢt ˢtː Fricatives s sː x <h> Nasals m mː n nː Glides w j <y> (w) Long consonants written with doubled letters. (Derrick and Weber n.d.; Weber 2020) 4 / 59 Predictable mid vowels? (Frantz 2017) Many [ɛː] and [ɔː] arise from coalescence across boundaries ◦ /a+i/ ! [ɛː] ◦ /a+o/ ! [ɔː] Vowel inventory front central back high i iː o oː mid ɛː <ai> ɔː <ao> low a aː (Derrick and Weber n.d.; Weber 2020) 5 / 59 Vowel inventory front central back high i iː o oː mid ɛː <ai> ɔː <ao> low a aː Predictable mid vowels? (Frantz 2017) Many [ɛː] and [ɔː] arise from coalescence across boundaries ◦ /a+i/ ! [ɛː] ◦ ! /a+o/ [ɔː] (Derrick and Weber n.d.; Weber 2020) 5 / 59 Contrastive mid vowels Some [ɛː] and [ɔː] are morpheme-internal, in overlapping environments with other long vowels JɔːníːtK JaːníːtK aoníít aaníít [ao–n/i–i]–t–Ø [aan–ii]–t–Ø [hole–by.needle/ti–ti1]–2sg.imp–imp [say–ai]–2sg.imp–imp ‘pierce it!’ ‘say (s.t.)!’ (Weber 2020) 6 / 59 Syntax within the stem Intransitive (bi-morphemic) vs. syntactically transitive (trimorphemic). Transitive V is object agreement (Quinn 2006; Rhodes 1994) p [ root –v0 –V0 ] Stem type Gloss ikinn –ssi AI ‘he is warm’ ikinn –ii II ‘it is warm’ itap –ip/i –thm TA ‘take him there’ itap –ip/ht –oo TI ‘take it there’ itap –ip/ht –aki AI(+O) ‘take (s.t.) there’ (Déchaine and Weber 2015, 2018; Weber 2020) 7 / 59 Syntax within the verbal complex Template p [ person–(preverb)*– [ –(med)–v–V ] –I0–C0 ] CP vP root vP CP ◦ Minimal verbal complex: stem plus suffixes (I0,C0). -

A Brief Description of Consonants in Modern Standard Arabic

Linguistics and Literature Studies 2(7): 185-189, 2014 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2014.020702 A Brief Description of Consonants in Modern Standard Arabic Iram Sabir*, Nora Alsaeed Al-Jouf University, Sakaka, KSA *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright © 2014 Horizon Research Publishing All rights reserved. Abstract The present study deals with “A brief Modern Standard Arabic. This study starts from an description of consonants in Modern Standard Arabic”. This elucidation of the phonetic bases of sounds classification. At study tries to give some information about the production of this point shows the first limit of the study that is basically Arabic sounds, the classification and description of phonetic rather than phonological description of sounds. consonants in Standard Arabic, then the definition of the This attempt of classification is followed by lists of the word consonant. In the present study we also investigate the consonant sounds in Standard Arabic with a key word for place of articulation in Arabic consonants we describe each consonant. The criteria of description are place and sounds according to: bilabial, labio-dental, alveolar, palatal, manner of articulation and voicing. The attempt of velar, uvular, and glottal. Then the manner of articulation, description has been made to lead to the drawing of some the characteristics such as phonation, nasal, curved, and trill. fundamental conclusion at the end of the paper. The aim of this study is to investigate consonant in MSA taking into consideration that all 28 consonants of Arabic alphabets. As a language Arabic is one of the most 2. -

Prosodic Identity in Copy Epenthesis Evidence for a Correspondence-Based Approach

Nat Lang Linguist Theory DOI 10.1007/s11049-017-9385-9 Prosodic identity in copy epenthesis Evidence for a correspondence-based approach Juliet Stanton1 · Sam Zukoff2 Received: 31 October 2016 / Accepted: 23 June 2017 © Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2017 Abstract This paper focuses on languages that exhibit processes of copy epenthe- sis, specifically those where the similarity between a copy vowel and its host ex- tends to prosodic or suprasegmental resemblance. We argue that copy vowels and their hosts strive for identity in all prosodic properties, and show that this drive for prosodic identity can cause misapplication in the assignment of properties such as stress and length. To explain these effects, we argue that any successful analysis of copy epenthesis must involve a correspondence relation (following Kitto and de Lacy 1999). Our proposal successfully predicts the extant typology of prosodic identity ef- fects in copy epenthesis; alternative analyses of copy epenthesis relying solely on fea- tural spreading (e.g. Kawahara 2007) or gestural realignment (e.g. Hall 2003, 2006) do not naturally capture the effects discussed here. Keywords Copy epenthesis · Phonology · Correspondence · Misapplication · Prosody 1 Introduction The term copy epenthesis describes a class of patterns in which the quality of an epenthetic vowel depends on the quality of one of its vocalic neighbors. For exam- ple: in a language where underlying /pri/ is realized as [piri] but /pra/ as [para] (not *[pira]), the vowel that appears in the unexpected position (the copy) is featurally identical to the vowel that appears in the expected position (its host). B J. -

LINGUISTICS 221 LECTURE #3 the BASIC SOUNDS of ENGLISH 1. STOPS a Stop Consonant Is Produced with a Complete Closure of Airflow

LINGUISTICS 221 LECTURE #3 Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology THE BASIC SOUNDS OF ENGLISH 1. STOPS A stop consonant is produced with a complete closure of airflow in the vocal tract; the air pressure has built up behind the closure; the air rushes out with an explosive sound when released. The term plosive is also used for oral stops. ORAL STOPS: e.g., [b] [t] (= plosives) NASAL STOPS: e.g., [m] [n] (= nasals) There are three phases of stop articulation: i. CLOSING PHASE (approach or shutting phase) The articulators are moving from an open state to a closed state; ii. CLOSURE PHASE (= occlusion) Blockage of the airflow in the oral tract; iii. RELEASE PHASE Sudden reopening; it may be accompanied by a burst of air. ORAL STOPS IN ENGLISH a. BILABIAL STOPS: The blockage is made with the two lips. spot [p] voiceless baby [b] voiced 1 b. ALVEOLAR STOPS: The blade (or the tip) of the tongue makes a closure with the alveolar ridge; the sides of the tongue are along the upper teeth. lamino-alveolar stops or Check your apico-alveolar stops pronunciation! stake [t] voiceless deep [d] voiced c. VELAR STOPS: The closure is between the back of the tongue (= dorsum) and the velum. dorso-velar stops scar [k] voiceless goose [g] voiced 2. NASALS (= nasal stops) The air is stopped in the oral tract, but the velum is lowered so that the airflow can go through the nasal tract. All nasals are voiced. NASALS IN ENGLISH a. BILABIAL NASAL: made [m] b. ALVEOLAR NASAL: need [n] c. -

Phonological Processes

Phonological Processes Phonological processes are patterns of articulation that are developmentally appropriate in children learning to speak up until the ages listed below. PHONOLOGICAL PROCESS DESCRIPTION AGE ACQUIRED Initial Consonant Deletion Omitting first consonant (hat → at) Consonant Cluster Deletion Omitting both consonants of a consonant cluster (stop → op) 2 yrs. Reduplication Repeating syllables (water → wawa) Final Consonant Deletion Omitting a singleton consonant at the end of a word (nose → no) Unstressed Syllable Deletion Omitting a weak syllable (banana → nana) 3 yrs. Affrication Substituting an affricate for a nonaffricate (sheep → cheep) Stopping /f/ Substituting a stop for /f/ (fish → tish) Assimilation Changing a phoneme so it takes on a characteristic of another sound (bed → beb, yellow → lellow) 3 - 4 yrs. Velar Fronting Substituting a front sound for a back sound (cat → tat, gum → dum) Backing Substituting a back sound for a front sound (tap → cap) 4 - 5 yrs. Deaffrication Substituting an affricate with a continuant or stop (chip → sip) 4 yrs. Consonant Cluster Reduction (without /s/) Omitting one or more consonants in a sequence of consonants (grape → gape) Depalatalization of Final Singles Substituting a nonpalatal for a palatal sound at the end of a word (dish → dit) 4 - 6 yrs. Stopping of /s/ Substituting a stop sound for /s/ (sap → tap) 3 ½ - 5 yrs. Depalatalization of Initial Singles Substituting a nonpalatal for a palatal sound at the beginning of a word (shy → ty) Consonant Cluster Reduction (with /s/) Omitting one or more consonants in a sequence of consonants (step → tep) Alveolarization Substituting an alveolar for a nonalveolar sound (chew → too) 5 yrs. -

A Comparative Analysis of Consonants in Chinese and Arabic Phonetics

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, November 2019, Vol. 9, No. 11, 1188-1193 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2019.11.010 D DAVID PUBLISHING A Comparative Analysis of Consonants in Chinese and Arabic Phonetics FAYROUZ ABDELSAMIE ELSAYED MOHAMED School of International Chinese Studies (SICS) of East China Normal University (ECNU), Shanghai , China Arabic and Chinese are one of the most difficult languages to learn in the world. The mark of Arabic is Pinyin characters plus pinyin symbols. On the other hand, the mark of Chinese is ideographic square shaped characters; each pronunciation of a Chinese character is generally a syllable. There are great differences between Arabic and Chinese consonants, so this paper mainly discusses the similarities and differences between the two languages and their respective characteristics through the comparative analysis of Chinese and Arabic consonants. Keywords: Chinese, Arabic, pronunciation, consonant, comparison A Comparative Analysis of Chinese and Arabic Consonants In order to make a comparative analysis of Chinese and Arabic consonants, first of all, we need to have a quite comprehensive and clear understanding of the features of each consonant pronunciation of the two languages. All consonant phonemes in Chinese and Arabic are included in Table 2 below. The Chinese phonetic symbol is Pinyin, which uses the International Latin alphabets. It has both consonant and vowel letters, while Arabic is phonetic alphabets transcription and the phonetic symbol of consonants is Arabic letters itself. Chinese language has 22 consonant phonemes; among them [ŋ] can only be used as a tail vowel, [n] can be used as both initial and final, and the rest can only be used as initials. -

Acoustic-Phonetics of Coronal Stops

Acoustic-phonetics of coronal stops: A cross-language study of Canadian English and Canadian French ͒ Megha Sundaraa School of Communication Sciences & Disorders, McGill University 1266 Pine Avenue West, Montreal, QC H3G 1A8 Canada ͑Received 1 November 2004; revised 24 May 2005; accepted 25 May 2005͒ The study was conducted to provide an acoustic description of coronal stops in Canadian English ͑CE͒ and Canadian French ͑CF͒. CE and CF stops differ in VOT and place of articulation. CE has a two-way voicing distinction ͑in syllable initial position͒ between simultaneous and aspirated release; coronal stops are articulated at alveolar place. CF, on the other hand, has a two-way voicing distinction between prevoiced and simultaneous release; coronal stops are articulated at dental place. Acoustic analyses of stop consonants produced by monolingual speakers of CE and of CF, for both VOT and alveolar/dental place of articulation, are reported. Results from the analysis of VOT replicate and confirm differences in phonetic implementation of VOT across the two languages. Analysis of coronal stops with respect to place differences indicates systematic differences across the two languages in relative burst intensity and measures of burst spectral shape, specifically mean frequency, standard deviation, and kurtosis. The majority of CE and CF talkers reliably and consistently produced tokens differing in the SD of burst frequency, a measure of the diffuseness of the burst. Results from the study are interpreted in the context of acoustic and articulatory data on coronal stops from several other languages. © 2005 Acoustical Society of America. ͓DOI: 10.1121/1.1953270͔ PACS number͑s͒: 43.70.Fq, 43.70.Kv, 43.70.Ϫh ͓AL͔ Pages: 1026–1037 I. -

UC Santa Barbara Dotawo: a Journal of Nubian Studies

UC Santa Barbara Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies Title The Consonant System of Abu Jinuk (Kordofan Nubian) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3kf38308 Journal Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies, 2(1) Author Alshareef, Waleed Publication Date 2015-06-01 DOI 10.5070/D62110020 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Consonant System of 155 Abu Jinuk (Kordofan Nubian) Waleed Alshareef 1. Introduction Abu Jinuk is a Kordofan Nubian language mainly spoken in the northwestern Nuba Mountains of Sudan. Kordofan Nubian is a branch of the Nubian language family. According to Rilly,1 Nubian belongs to the northern East Sudanic subgroup which is part of the East Sudanic branch of the Nilo-Saharan phylum. According to the Sultan of the Abu Jinuk tribe, the population in 2010 was 5,896 of whom 3,556 speakers live in the Nuba Moun- tains and 2,340 are scattered in different towns of Sudan.2 Accord- ing to the informants, the people call themselves and their language [d̪εkla] meaning “the great grandfather.” The Arabic term “Abu Ji- nuk,” by which they are known in linguistic literature, is the name of their mountain. By the non-Arab neighboring groups, the Abu Jinuk people are called [εlεk], which means “the explorers.” Abu Jinuk is an undescribed language. No linguistic studies have been devoted to the phonology of this language. Therefore, exam- ining the consonant system of Abu Jinuk is thought to be the first linguistic investigation of this language. -

Vowel Acoustics Reliably Differentiate Three Coronal Stops of Wubuy Across Prosodic Contexts

Vowel acoustics reliably differentiate three coronal stops of Wubuy across prosodic contexts Rikke L. BundgaaRd-nieLsena, BRett J. BakeRb, ChRistian kRoosa, MaRk haRveyc and CatheRine t. Besta,d aMARCS Auditory Laboratories, University of Western Sydney bSchool of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne cSchool of Humanities and Social Science, University of Newcastle dHaskins Laboratories, New Haven Abstract The present study investigates the acoustic differentiation of three coronal stops in the indigenous Australian language Wubuy. We test independent claims that only VC (vowel-into-consonant) transitions provide robust acoustic cues for retroflex as compared to alveolar and dental coronal stops, with no differentiating cues among these three coronal stops evident in CV (consonant-into-vowel) transitions. The four-way stop distinction /t, t̪ , ʈ, c/ in Wubuy is contrastive word-initially (Heath 1984) and by implication utterance-initially, i.e., in CV-only contexts, which suggests that acoustic differentiation should be expected to occur in the CV transitions of this language, including in initial positions. Therefore, we examined both VC and CV formant transition information in the three target coronal stops across VCV (word-internal), V#CV (word-initial but utterance-medial) and ##CV (word- and utterance-initial), for /a / vowel contexts, which provide the optimal environment for investigating formant transitions. Results confirm that these coro- nal contrasts are maintained in the CVs in this vowel context, and in all three posi- tions. The patterns of acoustic differences across the three syllable contexts also provide some support for a systematic role of prosodic boundaries in influencing the degree of coronal stop differentiation evident in the vowel formant transitions. -

Issue 31.2.Indd

Akanlig-Pare, G../Legon Journal of the Humanities Vol. 31.2 (2020) DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ljh.v31i2 .3 Palatalization in Central Bùlì George Akanlig-Pare Senior Lecturer University of Ghana, Legon Email: [email protected] Submitted: May 6, 2020/Accepted: November 20, 2020/Published: January 28, 2021 Abstract Palatalization is a process through which non-palatal consonants acquire palatality, either through a shift in place of articulation from a non-palatal region to the hard palate or through the superimposition of palatal qualities on a non-palatal consonant. In both cases, there is a front, non-low vowel or a palatal glide that triggers the process. In this paper, I examine the palatalization phenomena in Bùlì using Feature Geometry within the non- linear generative phonological framework. I argue that both full and secondary palatalization occur in Buli. The paper further explains that, the long high front vowel /i:/, triggers the formation of a palato-alveolar aff ricate which is realized in the Central dialect of Bùlì, where the Northern and Central dialects retain the derived palatal stop. Keywords: Palatalization, Bùlì, Feature Geometry, synchronic, diachronic Introduction Although linguists generally agree that palatalization is a process through which non-palatal consonants acquire palatality, they diff er in their accounts of the phonological processes that characterize it. As Halle (2005, p.1) states, “… palatalization raises numerous theoretical questions about which there is at present no agreement among phonologists”. Cross linguistic surveys conducted on the process reveal a number of issues that lead to the present state of aff airs. -

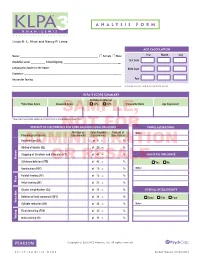

Sample, Not for Administration Or Resale

ANALYSIS FORM Linda M. L. Khan and Nancy P. Lewis Age Calculation Name: ______________________________________________________ u Female u Male Year Month Day Test Date Grade/Ed. Level: __________ School/Agency: __________________________________________ Language(s) Spoken in the Home: ___________________________________________________ Birth Date Examiner: ____________________________________________________________________ Reason for Testing: ______________________________________________________________ Age ____________________________________________________________________________ Reminder: Do not round up to next month or year. KLPA–3 Score Summary Confidence Interval *Total Raw Score Standard Score 90% 95% Percentile Rank Age Equivalent SAMPLE,– * Raw score equals total number of occurrences of scored phonological processes. Percent of OccurrenceNOT for Core Phonological ProcessesFOR Vowel Alterations Number of Total Possible Percent of Notes: Phonological Process Occurrences Occurrences Occurrences DeaffricationADMINISTRATION (DF) of 8 = % Gliding of liquids (GL) of 20 = % Stopping of fricatives and affricates (ST) of 48 = % Dialectal Influence Manner OR RESALE Stridency deletion (STR) of 42 = % Yes No Vocalization (VOC) of 15 = % Notes: Palatal fronting (PF) of 12 = % Place Velar fronting (VF) of 23 = % Cluster simplification (CS) of 23 = % Overall Intelligibility Deletion of final consonant (DFC) of 36 = % Good Fair Poor Reduction Syllable reduction (SR) of 25 = % Notes: Final devoicing (FDV) of 35 = % Voicing Initial voicing -

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin

LT3212 Phonetics Assignment 4 Mavis, Wong Chak Yin Essay Title: The sound system of Japanese This essay aims to introduce the sound system of Japanese, including the inventories of consonants, vowels, and diphthongs. The phonological variations of the sound segments in different phonetic environments are also included. For the illustration, word examples are given and they are presented in the following format: [IPA] (Romaji: “meaning”). Consonants In Japanese, there are 14 core consonants, and some of them have a lot of allophonic variations. The various types of consonants classified with respect to their manner of articulation are presented as follows. Stop Japanese has six oral stops or plosives, /p b t d k g/, which are classified into three place categories, bilabial, alveolar, and velar, as listed below. In each place category, there is a pair of plosives with the contrast in voicing. /p/ = a voiceless bilabial plosive [p]: [ippai] (ippai: “A cup of”) /b/ = a voiced bilabial plosive [b]: [baɴ] (ban: “Night”) /t/ = a voiceless alveolar plosive [t]: [oto̞ ːto̞ ] (ototo: “Brother”) /d/ = a voiced alveolar plosive [d]: [to̞ mo̞ datɕi] (tomodachi: “Friend”) /k/ = a voiceless velar plosive [k]: [kaiɰa] (kaiwa: “Conversation”) /g/ = a voiced velar plosive [g]: [ɡakɯβsai] (gakusai: “Student”) Phonetically, Japanese also has a glottal stop [ʔ] which is commonly produced to separate the neighboring vowels occurring in different syllables. This phonological phenomenon is known as ‘glottal stop insertion’. The glottal stop may be realized as a pause, which is used to indicate the beginning or the end of an utterance. For instance, the word “Japanese money” is actually pronounced as [ʔe̞ ɴ], instead of [je̞ ɴ], and the pronunciation of “¥15” is [dʑɯβːɡo̞ ʔe̞ ɴ].