“AN ABYSS of ANARCHY, NIHILISM, and DESPAIR”: HISTORICAL REPRESENTATIONS of ANARCHISTS in BRITAIN by Alexander Lee Jutila A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

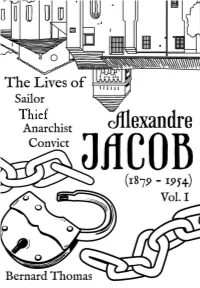

Bernard Thomas Volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M

Thief Jacob Alexandre Marius alias Escande Attila George Bonnot Féran Hard to Kill the Robber Bernard Thomas volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno First Published by Tchou Éditions 1970 This edition translated by Paul Sharkey footnotes translated by Laetitia Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno translated by Jean Weir Published in September 2010 by Elephant Editions and Bandit Press Elephant Editions Ardent Press 2013 introduction i the bandits 1 the agitator 37 introduction The impossibility of a perspective that is fully organized in all its details having been widely recognised, rigor and precision have disappeared from the field of human expectations and the need for order and security have moved into the sphere of desire. There, a last fortress built in fret and fury, it has established a foothold for the final battle. Desire is sacred and inviolable. It is what we hold in our hearts, child of our instincts and father of our dreams. We can count on it, it will never betray us. The newest graves, those that we fill in the edges of the cemeteries in the suburbs, are full of this irrational phenomenology. We listen to first principles that once would have made us laugh, assigning stability and pulsion to what we know, after all, is no more than a vague memory of a passing wellbeing, the fleeting wing of a gesture in the fog, the flapping morning wings that rapidly ceded to the needs of repetitiveness, the obsessive and disrespectful repetitiveness of the bureaucrat lurking within us in some dark corner where we select and codify dreams like any other hack in the dissecting rooms of repression. -

Libertarian Marxism Mao-Spontex Open Marxism Popular Assembly Sovereign Citizen Movement Spontaneism Sui Iuris

Autonomist Marxist Theory and Practice in the Current Crisis Brian Marks1 University of Arizona School of Geography and Development [email protected] Abstract Autonomist Marxism is a political tendency premised on the autonomy of the proletariat. Working class autonomy is manifested in the self-activity of the working class independent of formal organizations and representations, the multiplicity of forms that struggles take, and the role of class composition in shaping the overall balance of power in capitalist societies, not least in the relationship of class struggles to the character of capitalist crises. Class composition analysis is applied here to narrate the recent history of capitalism leading up to the current crisis, giving particular attention to China and the United States. A global wave of struggles in the mid-2000s was constituitive of the kinds of working class responses to the crisis that unfolded in 2008-10. The circulation of those struggles and resultant trends of recomposition and/or decomposition are argued to be important factors in the balance of political forces across the varied geography of the present crisis. The whirlwind of crises and the autonomist perspective The whirlwind of crises (Marks, 2010) that swept the world in 2008, financial panic upon food crisis upon energy shock upon inflationary spiral, receded temporarily only to surge forward again, leaving us in a turbulent world, full of possibility and peril. Is this the end of Neoliberalism or its retrenchment? A new 1 Published under the Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works Autonomist Marxist Theory and Practice in the Current Crisis 468 New Deal or a new Great Depression? The end of American hegemony or the rise of an “imperialism with Chinese characteristics?” Or all of those at once? This paper brings the political tendency known as autonomist Marxism (H. -

When Fear Is Substituted for Reason: European and Western Government Policies Regarding National Security 1789-1919

WHEN FEAR IS SUBSTITUTED FOR REASON: EUROPEAN AND WESTERN GOVERNMENT POLICIES REGARDING NATIONAL SECURITY 1789-1919 Norma Lisa Flores A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2012 Committee: Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Dr. Mark Simon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Brooks Dr. Geoff Howes Dr. Michael Jakobson © 2012 Norma Lisa Flores All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Although the twentieth century is perceived as the era of international wars and revolutions, the basis of these proceedings are actually rooted in the events of the nineteenth century. When anything that challenged the authority of the state – concepts based on enlightenment, immigration, or socialism – were deemed to be a threat to the status quo and immediately eliminated by way of legal restrictions. Once the façade of the Old World was completely severed following the Great War, nations in Europe and throughout the West started to revive various nineteenth century laws in an attempt to suppress the outbreak of radicalism that preceded the 1919 revolutions. What this dissertation offers is an extended understanding of how nineteenth century government policies toward radicalism fostered an environment of increased national security during Germany’s 1919 Spartacist Uprising and the 1919/1920 Palmer Raids in the United States. Using the French Revolution as a starting point, this study allows the reader the opportunity to put events like the 1848 revolutions, the rise of the First and Second Internationals, political fallouts, nineteenth century imperialism, nativism, Social Darwinism, and movements for self-government into a broader historical context. -

Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................2 2. The Principles of Anarchism, Lucy Parsons....................................................................3 3. Anarchism and the Black Revolution, Lorenzo Komboa’Ervin......................................10 4. Beyond Nationalism, But not Without it, Ashanti Alston...............................................72 5. Anarchy Can’t Fight Alone, Kuwasi Balagoon...............................................................76 6. Anarchism’s Future in Africa, Sam Mbah......................................................................80 7. Domingo Passos: The Brazilian Bakunin.......................................................................86 8. Where Do We Go From Here, Michael Kimble..............................................................89 9. Senzala or Quilombo: Reflections on APOC and the fate of Black Anarchism, Pedro Riberio...........................................................................................................................91 10. Interview: Afro-Colombian Anarchist David López Rodríguez, Lisa Manzanilla & Bran- don King........................................................................................................................96 11. 1996: Ballot or the Bullet: The Strengths and Weaknesses of the Electoral Process in the U.S. and its relation to Black political power today, Greg Jackson......................100 12. The Incomprehensible -

Lauri Love -V- the Government of the United States of America & Liberty

Neutral Citation Number: [2018] EWHC 172 (Admin) Case No: CO/5994/2016 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION ADMINISTRATIVE COURT Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 05/02/2018 Before: THE RIGHT HONOURABLE THE LORD BURNETT OF MALDON THE LORD CHIEF JUSTICE and THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE OUSELEY - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: LAURI LOVE Appellant - and - THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES Respondent OF AMERICA - and - LIBERTY Interested Party - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - MR EDWARD FITZGERALD QC AND MR BEN COOPER (instructed by KAIM TODNER SOLICITORS LTD) for the Appellant MR PETER CALDWELL (instructed by CPS EXTRADITION UNIT) for the Respondent MR ALEX BAILIN QC AND MR AARON WATKINS (instructed by LIBERTY) for the Interested Party Hearing dates: 29 and 30 November 2017 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. Love v USA THE LORD CHIEF JUSTICE AND MR JUSTICE OUSELEY : 1. This is the judgment of the Court. 2. Lauri Love appeals against the decision of District Judge Tempia, sitting at Westminster Magistrates’ Court on 16 September 2016, to send his case to the Secretary of State for the Home Department for her decision whether to order his extradition to the United States of America, under Part 2 of the Extradition Act 2003 [“the 2003 Act”]. The USA is a category 2 territory under that Act. On 14 November 2016, the Home Secretary ordered his extradition. 3. The principal -

'The Italians and the IWMA'

Levy, Carl. 2018. ’The Italians and the IWMA’. In: , ed. ”Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth”. The First International in Global Perspective. 29 The Hague: Brill, pp. 207-220. ISBN 978-900-4335-455 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/23423/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. -

Spaziergang in Genf, Lausanne, Vevey Und St

Dr. Elemér Hantos-Stiftung www.swissworld.org Your Gateway to Switzerland Studienreise Schweiz 18. – 25. Juni 2011 Reiseberichte Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort . 1 Sonntag . 4 Genf, Genfersee, Vevey, Rivaz Montag . 8 Genf Dienstag . 11 Solothurn, Pfäffikon SZ Mittwoch . 17 Zürich, Schlieren Donnerstag . 27 Sankt Gallen Freitag . 32 Bern, Muri, der Niesen Samstag . 41 Bern, Genf Bildernachweis . 42 Abschlussredaktion: PhilipP Siegert Vorwort Die Andrássy Universität Budapest (AUB) ist die einzige deutschsprachige Universität Ungarns. Sie wird von Ungarn gemeinsam mit Österreich und Deutschland, insbesondere den Bundesländern Bayern und Baden-Württemberg getragen und auch von der Schweiz tatkräftig unterstützt. Die Gründungsidee der AUB ist es, eine Institution zur Postgradualen Ausbildung von Führungskräften für nationale, euroPäische und internationale Institutionen sowie Unternehmen zu schaffen. Neben der starken euroPäischen Orientierung weist die AUB auch einen ausgeprägten regionalen Bezug auf. Forschung und Lehre an der AUB zeichnen sich durch einen interdisziPlinären Ansatz aus. Auch hinsichtlich der Studierenden und Dozierenden ist die Universität multinational ausgerichtet. Die fruchtbare Auseinandersetzung mit kultureller Diversität bildet einen integrierenden Bestandteil des Ausbildungskonzepts. Die Schweiz leistet einen bedeutenden Beitrag zu den Zielen der AUB. Zur Zeit sind vier Dozierende aus der Schweiz mit unterschiedlich hohen Pensen an der Universität tätig. Es ist ihnen ein großes Anliegen, bei den Studierenden der AUB, die die zukünftigen Führungskräfte in den Bereichen Wirtschaft, Verwaltung, DiPlomatie und Kulturmanagement in Ost- und MitteleuroPa – aber auch der EU – repräsentieren, ein wohlwollendes Verständnis für die Schweiz zu schaffen. Verständnis setzt Wissen voraus. Aus diesem Grunde werden im Rahmen der regulären Lehrveranstaltungen an der AUB regelmäßig Fächer mit einem Schweizbezug angeboten oder wichtige Fragen der internationalen Politik und des Völkerrechts aus einer spezifisch schweizerischen Perspektive erörtert. -

USA -V- Julian Assange Judgment

JUDICIARY OF ENGLAND AND WALES District Judge (Magistrates’ Court) Vanessa Baraitser In the Westminster Magistrates’ Court Between: THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Requesting State -v- JULIAN PAUL ASSANGE Requested Person INDEX Page A. Introduction 2 a. The Request 2 b. Procedural History (US) 3 c. Procedural History (UK) 4 B. The Conduct 5 a. Second Superseding Indictment 5 b. Alleged Conduct 9 c. The Evidence 15 C. Issues Raised 15 D. The US-UK Treaty 16 E. Initial Stages of the Extradition Hearing 25 a. Section 78(2) 25 b. Section 78(4) 26 I. Section 78(4)(a) 26 II. Section 78(4)(b) 26 i. Section 137(3)(a): The Conduct 27 ii. Section 137(3)(b): Dual Criminality 27 1 The first strand (count 2) 33 The second strand (counts 3-14,1,18) and Article 10 34 The third strand (counts 15-17, 1) and Article 10 43 The right to truth/ Necessity 50 iii. Section 137(3)(c): maximum sentence requirement 53 F. Bars to Extradition 53 a. Section 81 (Extraneous Considerations) 53 I. Section 81(a) 55 II. Section 81(b) 69 b. Section 82 (Passage of Time) 71 G. Human Rights 76 a. Article 6 84 b. Article 7 82 c. Article 10 88 H. Health – Section 91 92 a. Prison Conditions 93 I. Pre-Trial 93 II. Post-Trial 98 b. Psychiatric Evidence 101 I. The defence medical evidence 101 II. The US medical evidence 105 III. Findings on the medical evidence 108 c. The Turner Criteria 111 I. -

Human-Computer Insurrection

Human-Computer Insurrection Notes on an Anarchist HCI Os Keyes∗ Josephine Hoy∗ Margaret Drouhard∗ University of Washington University of Washington University of Washington Seattle, WA, USA Seattle, WA, USA Seattle, WA, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 2019), May 4–9, 2019, Glasgow, Scotland, UK. ACM, New York, NY, The HCIcommunity has worked to expand and improve our USA, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300569 consideration of the societal implications of our work and our corresponding responsibilities. Despite this increased 1 INTRODUCTION engagement, HCI continues to lack an explicitly articulated "You are ultimately—consciously or uncon- politic, which we argue re-inscribes and amplifies systemic sciously—salesmen for a delusive ballet in oppression. In this paper, we set out an explicit political vi- the ideas of democracy, equal opportunity sion of an HCI grounded in emancipatory autonomy—an an- and free enterprise among people who haven’t archist HCI, aimed at dismantling all oppressive systems by the possibility of profiting from these." [74] mandating suspicion of and a reckoning with imbalanced The last few decades have seen HCI take a turn to exam- distributions of power. We outline some of the principles ine the societal implications of our work: who is included and accountability mechanisms that constitute an anarchist [10, 68, 71, 79], what values it promotes or embodies [56, 57, HCI. We offer a potential framework for radically reorient- 129], and how we respond (or do not) to social shifts [93]. ing the field towards creating prefigurative counterpower—systems While this is politically-motivated work, HCI has tended to and spaces that exemplify the world we wish to see, as we avoid making our politics explicit [15, 89]. -

The Italians and the Iwma

chapter �3 The Italians and the iwma Carl Levy Introduction Italians played a significant and multi-dimensional role in the birth, evolution and death of the First International, and indeed in its multifarious afterlives: the International Working Men's Association (iwma) has also served as a milestone or foundation event for histories of Italian anarchism, syndicalism, socialism and communism.1 The Italian presence was felt simultaneously at the national, international and transnational levels from 1864 onwards. In this chapter I will first present a brief synoptic overview of the history of the iwma (in its varied forms) in Italy and abroad from 1864 to 1881. I will then exam- ine interpretations of aspects of Italian Internationalism: Mazzinian Repub- licanism and the origins of anarchism, the Italians, Bakunin and interactions with Marx and his ideas, the theory and practice of propaganda by the deed and the rise of a third-way socialism neither fully reformist nor revolutionary, neither Marxist nor anarchist. This chapter will also include some brief words on the sociology and geography of Italian Internationalism and a discussion of newer approaches that transcend the rather stale polemics between parti- sans of a Marxist or anarchist reading of Italian Internationalism and incorpo- rates themes that have enlivened the study of the Risorgimento, namely, State responses to the International, the role of transnationalism, romanticism, 1 The best overviews of the iwma in Italy are: Pier Carlo Masini, La Federazione Italiana dell’Associazione Internazionale dei Lavoratori. Atti ufficiali 1871–1880 (atti congressuali; indirizzi, proclaim, manifesti) (Milan, 1966); Pier Carlo Masini, Storia degli Anarchici Ital- iani da Bakunin a Malatesta, (Milan, (1969) 1974); Nunzio Pernicone, Italian Anarchism 1864–1892 (Princeton, 1993); Renato Zangheri, Storia del socialismo italiano. -

Anarcho-Syndicalism in the 20Th Century

Anarcho-syndicalism in the 20th Century Vadim Damier Monday, September 28th 2009 Contents Translator’s introduction 4 Preface 7 Part 1: Revolutionary Syndicalism 10 Chapter 1: From the First International to Revolutionary Syndicalism 11 Chapter 2: the Rise of the Revolutionary Syndicalist Movement 17 Chapter 3: Revolutionary Syndicalism and Anarchism 24 Chapter 4: Revolutionary Syndicalism during the First World War 37 Part 2: Anarcho-syndicalism 40 Chapter 5: The Revolutionary Years 41 Chapter 6: From Revolutionary Syndicalism to Anarcho-syndicalism 51 Chapter 7: The World Anarcho-Syndicalist Movement in the 1920’s and 1930’s 64 Chapter 8: Ideological-Theoretical Discussions in Anarcho-syndicalism in the 1920’s-1930’s 68 Part 3: The Spanish Revolution 83 Chapter 9: The Uprising of July 19th 1936 84 2 Chapter 10: Libertarian Communism or Anti-Fascist Unity? 87 Chapter 11: Under the Pressure of Circumstances 94 Chapter 12: The CNT Enters the Government 99 Chapter 13: The CNT in Government - Results and Lessons 108 Chapter 14: Notwithstanding “Circumstances” 111 Chapter 15: The Spanish Revolution and World Anarcho-syndicalism 122 Part 4: Decline and Possible Regeneration 125 Chapter 16: Anarcho-Syndicalism during the Second World War 126 Chapter 17: Anarcho-syndicalism After World War II 130 Chapter 18: Anarcho-syndicalism in contemporary Russia 138 Bibliographic Essay 140 Acronyms 150 3 Translator’s introduction 4 In the first decade of the 21st century many labour unions and labour feder- ations worldwide celebrated their 100th anniversaries. This was an occasion for reflecting on the past century of working class history. Mainstream labour orga- nizations typically understand their own histories as never-ending struggles for better working conditions and a higher standard of living for their members –as the wresting of piecemeal concessions from capitalists and the State. -

KARL MARX Peter Harrington London Peter Harrington London

KARL MARX Peter Harrington london Peter Harrington london mayfair chelsea Peter Harrington Peter Harrington 43 dover street 100 FulHam road london w1s 4FF london sw3 6Hs uk 020 3763 3220 uk 020 7591 0220 eu 00 44 20 3763 3220 eu 00 44 20 7591 0220 usa 011 44 20 3763 3220 www.peterharrington.co.uk usa 011 44 20 7591 0220 Peter Harrington london KARL MARX remarkable First editions, Presentation coPies, and autograPH researcH notes ian smitH, senior sPecialist in economics, Politics and PHilosoPHy [email protected] Marx: then and now We present a remarkable assembly of first editions and presentation copies of the works of “The history of the twentieth Karl Marx (1818–1883), including groundbreaking books composed in collaboration with century is Marx’s legacy. Stalin, Mao, Che, Castro … have all Friedrich Engels (1820–1895), early articles and announcements written for the journals presented themselves as his heirs. Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher and Der Vorbote, and scathing critical responses to the views of Whether he would recognise his contemporaries Bauer, Proudhon, and Vogt. them as such is quite another matter … Nevertheless, within one Among this selection of highlights are inscribed copies of Das Kapital (Capital) and hundred years of his death half Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei (Communist Manifesto), the latter being the only copy of the the world’s population was ruled Manifesto inscribed by Marx known to scholarship; an autograph manuscript leaf from his by governments that professed Marxism to be their guiding faith. years spent researching his theory of capital at the British Museum; a first edition of the His ideas have transformed the study account of the First International’s 1866 Geneva congress which published Marx’s eleven of economics, history, geography, “instructions”; and translations of his works into Russian, Italian, Spanish, and English, sociology and literature.” which begin to show the impact that his revolutionary ideas had both before and shortly (Francis Wheen, Karl Marx, 1999) after his death.