Pharmacological Management of Epilepsy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 6.12: Deaths from Poisoning, by Sex and Cause, Scotland, 2016

Table 6.12: Deaths from poisoning, by sex and cause, Scotland, 2016 ICD code(s), cause of death and substance(s) 1 Both Males Females ALL DEATHS FROM POISONING 2 1130 766 364 ACCIDENTS 850 607 243 X40 - X49 Accidental poisoning by and exposure to … X40 - Nonopioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics Paracetamol 2 1 1 Paracetamol, Cocaine, Amphetamine || 1 0 1 X41 - Antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic, antiparkinsonism and psychotropic drugs, not elsewhere classified Alprazolam, MDMA, Cocaine || Cannabis, Alcohol 1 1 0 Alprazolam, Methadone || Pregabalin, Tramadol, Gabapentin, Cannabis 1 1 0 Alprazolam, Morphine, Heroin, Dihydrocodeine, Buprenorphine || Alcohol 1 1 0 Alprazolam, Oxycodone, Alcohol || Paracetamol 1 0 1 Amitriptyline, Cocaine, Etizolam || Paracetamol, Codeine, Hydrocodone, Alcohol 1 1 0 Amitriptyline, Dihydrocodeine || Diazepam, Paracetamol, Verapamil, Alcohol 1 1 0 Amitriptyline, Fluoxetine, Alcohol 1 0 1 Amitriptyline, Methadone, Diazepam || 1 1 0 Amitriptyline, Methadone, Morphine, Etizolam || Gabapentin, Cannabis, Alcohol 1 1 0 Amitriptyline, Venlafaxine 1 0 1 Amphetamine 1 1 0 Amphetamine || 1 1 0 Amphetamine || Alcohol 1 1 0 Amphetamine || Chlorpromazine 1 1 0 Amphetamine || Fluoxetine 1 1 0 Amphetamine, Dihydrocodeine, Alcohol || Procyclidine, Tramadol, Duloxetine, Haloperidol 1 0 1 Amphetamine, MDMA || Diclazepam, Cannabis, Alcohol 1 1 0 Amphetamine, Methadone || 1 1 0 Amphetamine, Oxycodone, Gabapentin, Zopiclone, Diazepam || Paracetamol, Alcohol 1 0 1 Amphetamine, Tramadol || Mirtazapine, Alcohol 1 1 0 Benzodiazepine -

Drug Names That Are Too Close for Comfort

MEDICATION SAFETY Drug Names That Are Too Close for Comfort and therefore at risk of “seeing” prescriptions for the newer product clobazam as the more familiar clonazePAM. Use TWO IDENtifieRS at THE POS Within the span of a couple of days, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices received two more reports of wrong patient errors at the point-of-sale. Both were submitted by the parents of the patients involved. In one event, a teenager, who Look- and sound-alike similarity between the official names was supposed to receive methylphenidate for Attention Deficit clobazam (ONFI) and clonazePAM (KLONOPIN) has led Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), was given a cardiac drug to several reports expressing concern that patients may in- intended for a different patient. The mother who was picking advertently receive the wrong medication in either hospital up the prescription for her son caught the error because or outpatient settings. The drugs share similar indications, the pharmacist mentioned that “this will help with the chest although they have 10-fold strength difference in available pains.” Of course, this means that the other patient was given dosage forms. Clobazam was approved by Food and Drug the methylphenidate instead of the cardiac drug. It turned out Administration in October 2011 for adjunctive treatment of that the teenager and the other patient had the same name. Lennox-Gaustaut seizures and other epileptic syndromes. Lennox-Gaustaut is a form of childhood-onset epilepsy In the second case, a patient was dispensed amLODIPine, a characterized by frequent seizures and different seizure calcium channel blocker, instead of the anticonvulsant gab- types, often accompanied by developmental delay and apentin. -

S1 Table. List of Medications Analyzed in Present Study Drug

S1 Table. List of medications analyzed in present study Drug class Drugs Propofol, ketamine, etomidate, Barbiturate (1) (thiopental) Benzodiazepines (28) (midazolam, lorazepam, clonazepam, diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, oxazepam, potassium Sedatives clorazepate, bromazepam, clobazam, alprazolam, pinazepam, (32 drugs) nordazepam, fludiazepam, ethyl loflazepate, etizolam, clotiazepam, tofisopam, flurazepam, flunitrazepam, estazolam, triazolam, lormetazepam, temazepam, brotizolam, quazepam, loprazolam, zopiclone, zolpidem) Fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil, remifentanil, morphine, Opioid analgesics hydromorphone, nicomorphine, oxycodone, tramadol, (10 drugs) pethidine Acetaminophen, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (36) (celecoxib, polmacoxib, etoricoxib, nimesulide, aceclofenac, acemetacin, amfenac, cinnoxicam, dexibuprofen, diclofenac, emorfazone, Non-opioid analgesics etodolac, fenoprofen, flufenamic acid, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, (44 drugs) ketoprofen, ketorolac, lornoxicam, loxoprofen, mefenamiate, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, pranoprofen, proglumetacin, sulindac, talniflumate, tenoxicam, tiaprofenic acid, zaltoprofen, morniflumate, pelubiprofen, indomethacin), Anticonvulsants (7) (gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, valproic acid, lacosamide) Vecuronium, rocuronium bromide, cisatracurium, atracurium, Neuromuscular hexafluronium, pipecuronium bromide, doxacurium chloride, blocking agents fazadinium bromide, mivacurium chloride, (12 drugs) pancuronium, gallamine, succinylcholine -

Calculating Equivalent Doses of Oral Benzodiazepines

Calculating equivalent doses of oral benzodiazepines Background Benzodiazepines are the most commonly used anxiolytics and hypnotics (1). There are major differences in potency between different benzodiazepines and this difference in potency is important when switching from one benzodiazepine to another (2). Benzodiazepines also differ markedly in the speed in which they are metabolised and eliminated. With repeated daily dosing accumulation occurs and high concentrations can build up in the body (mainly in fatty tissues) (2). The degree of sedation that they induce also varies, making it difficult to determine exact equivalents (3). Answer Advice on benzodiazepine conversion NB: Before using Table 1, read the notes below and the Limitations statement at the end of this document. Switching benzodiazepines may be advantageous for a variety of reasons, e.g. to a drug with a different half-life pre-discontinuation (4) or in the event of non-availability of a specific benzodiazepine. With relatively short-acting benzodiazepines such as alprazolam and lorazepam, it is not possible to achieve a smooth decline in blood and tissue concentrations during benzodiazepine withdrawal. These drugs are eliminated fairly rapidly with the result that concentrations fluctuate with peaks and troughs between each dose. It is necessary to take the tablets several times a day and many people experience a "mini-withdrawal", sometimes a craving, between each dose. For people withdrawing from these potent, short-acting drugs it has been advised that they switch to an equivalent dose of a benzodiazepine with a long half life such as diazepam (5). Diazepam is available as 2mg tablets which can be halved to give 1mg doses. -

Deconstructing Tolerance with Clobazam Post Hoc Analyses from an Open-Label Extension Study

Deconstructing tolerance with clobazam Post hoc analyses from an open-label extension study Barry E. Gidal, PharmD ABSTRACT Robert T. Wechsler, MD, Objective: To evaluate potential development of tolerance to adjunctive clobazam in patients with PhD Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Raman Sankar, MD, PhD Methods: Eligible patients enrolled in open-label extension study OV-1004, which continued until Georgia D. Montouris, clobazam was commercially available in the United States or for a maximum of 2 years outside MD the United States. Enrolled patients started at 0.5 mg$kg21$d21 clobazam, not to exceed H. Steve White, PhD 40 mg/d. After 48 hours, dosages could be adjusted up to 2.0 mg$kg21$d21 (maximum 80 mg/d) James C. Cloyd, PharmD on the basis of efficacy and tolerability. Post hoc analyses evaluated mean dosages and drop- Mary Clare Kane, PhD seizure rates for the first 2 years of the open-label extension based on responder categories and Guangbin Peng, MS baseline seizure quartiles in OV-1012. Individual patient listings were reviewed for dosage David M. Tworek, MS, increases $40% and increasing seizure rates. MBA Vivienne Shen, MD, PhD Results: Data from 200 patients were included. For patients free of drop seizures, there was no Jouko Isojarvi, MD, PhD notable change in dosage over 24 months. For responder groups still exhibiting drop seizures, dosages were increased. Weekly drop-seizure rates for 100% and $75% responders demon- strated a consistent response over time. Few patients had a dosage increase $40% associated Correspondence to with an increase in seizure rates. Dr. Gidal: [email protected] Conclusions: Two-year findings suggest that the majority of patients do not develop tolerance to the antiseizure actions of clobazam. -

The Emergence of New Psychoactive Substance (NPS) Benzodiazepines

Issue: Ir Med J; Vol 112; No. 7; P970 The Emergence of New Psychoactive Substance (NPS) Benzodiazepines. A Survey of their Prevalence in Opioid Substitution Patients using LC-MS S. Mc Namara, S. Stokes, J. Nolan HSE National Drug Treatment Centre Abstract Benzodiazepines have a wide range of clinical uses being among the most commonly prescribed medicines globally. The EU Early Warning System on new psychoactive substances (NPS) has over recent years detected new illicit benzodiazepines in Europe’s drug market1. Additional reference standards were obtained and a multi-residue LC- MS method was developed to test for 31 benzodiazepines or metabolites in urine including some new benzodiazepines which have been classified as New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) which comprise a range of substances, including synthetic cannabinoids, opioids, cathinones and benzodiazepines not covered by international drug controls. 200 urine samples from patients attending the HSE National Drug Treatment Centre (NDTC) who are monitored on a regular basis for drug and alcohol use and which tested positive for benzodiazepine class drugs by immunoassay screening were subjected to confirmatory analysis to determine what Benzodiazepine drugs were present and to see if etizolam or other new benzodiazepines are being used in the addiction population currently. Benzodiazepine prescription and use is common in the addiction population. Of significance we found evidence of consumption of an illicit new psychoactive benzodiazepine, Etizolam. Introduction Benzodiazepines are useful in the short-term treatment of anxiety and insomnia, and in managing alcohol withdrawal. 1 According to the EMCDDA report on the misuse of benzodiazepines among high-risk opioid users in Europe1, benzodiazepines, especially when injected, can prolong the intensity and duration of opioid effects. -

Pharmaceuticals As Environmental Contaminants

PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals asas EnvironmentalEnvironmental Contaminants:Contaminants: anan OverviewOverview ofof thethe ScienceScience Christian G. Daughton, Ph.D. Chief, Environmental Chemistry Branch Environmental Sciences Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development Environmental Protection Agency Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 [email protected] Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Why and how do drugs contaminate the environment? What might it all mean? How do we prevent it? Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada This talk presents only a cursory overview of some of the many science issues surrounding the topic of pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada A Clarification We sometimes loosely (but incorrectly) refer to drugs, medicines, medications, or pharmaceuticals as being the substances that contaminant the environment. The actual environmental contaminants, however, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients – APIs. These terms are all often used interchangeably Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Office of Research and Development Available: http://www.epa.gov/nerlesd1/chemistry/pharma/image/drawing.pdfNational -

Clinical Considerations in Transitioning Patients with Epilepsy From

Sankar et al. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2014, 8:429 JOURNAL OF MEDICAL http://www.jmedicalcasereports.com/content/8/1/429 CASE REPORTS CASE REPORT Open Access Clinical considerations in transitioning patients with epilepsy from clonazepam to clobazam: a case series Raman Sankar1*, Steve Chung2, Michael Scott Perry3, Ruben Kuzniecky4 and Saurabh Sinha5 Abstract Introduction: In treating refractory epilepsy, many clinicians are interested in methods used to transition patients receiving clonazepam to clobazam to maintain or increase seizure control, improve tolerability of patients’ overall drug therapy regimens, and to enhance quality of life for patients and their families. However, no published guidelines assist clinicians in successfully accomplishing this change safely. Case presentations: The following three case reports provide insight into the transition from clonazepam to clobazam. First, an 8-year-old Caucasian boy with cryptogenic Lennox–Gastaut syndrome beginning at 3.5 years of age, who was experiencing multiple daily generalized tonic–clonic, absence, myoclonic, and tonic seizures at presentation. Second, a 25-year-old, left-handed, White Hispanic man with moderate mental retardation and medically refractory seizures that he began experiencing at 1 year of age, secondary to tuberous sclerosis. When first presented to an epilepsy center, he had been receiving levetiracetam, valproate, and clonazepam, but reported having ongoing and frequent seizures. Third, a 69-year-old Korean woman who had been healthy until she had a stroke in 2009 with subsequent right hemiparesis; as a result, she became less physically and socially active, and had her first convulsive seizure approximately 4 months after the stroke. Conclusions: From these cases, we observe that a rough estimate of final clobazam dosage for each mg of clonazepam under substitution is likely to be at least 10-fold, probably closer to 15-fold for many patients, and as high as 20-fold for a few. -

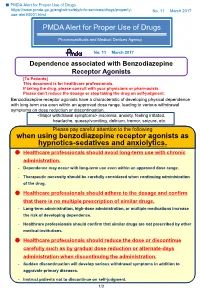

PMDA Alert for Proper Use of Drugs When Using Benzodiazepine

■ PMDA Alert for Proper Use of Drugs https://www.pmda.go.jp/english/safety/info-services/drugs/properly- No. 11 March 2017 use-alert/0001.html PMDA Alert for Proper Use of Drugs Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency No. 11 March 2017 Dependence associated with Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonists [To Patients] This document is for healthcare professionals. If taking the drug, please consult with your physicians or pharmacists. Please don’t reduce the dosage or stop taking the drug on self-judgment. Benzodiazepine receptor agonists have a characteristic of developing physical dependence with long-term use even within an approved dose range, leading to various withdrawal symptoms on dose reduction or discontinuation. <Major withdrawal symptoms> insomnia, anxiety, feeling irritated, headache, queasy/vomiting, delirium, tremor, seizure, etc. Please pay careful attention to the following when using benzodiazepine receptor agonists as hypnotics-sedatives and anxiolytics. Healthcare professionals should avoid long-term use with chronic administration. - Dependence may occur with long-term use even within an approved dose range. - Therapeutic necessity should be carefully considered when continuing administration of the drug. Healthcare professionals should adhere to the dosage and confirm that there is no multiple prescription of similar drugs. - Long-term administration, high-dose administration, or multiple medications increase the risk of developing dependence. - Healthcare professionals should confirm that similar drugs are not prescribed by other medical institutions. Healthcare professionals should reduce the dose or discontinue carefully such as by gradual dose reduction or alternate-days administration when discontinuing the administration. - Sudden discontinuation will develop serious withdrawal symptoms in addition to aggravate primary diseases. -

Focus on Benzodiazepines

Graylands Hospital Drug Bulletin Focus on Benzodiazepines North Metropolitan Health Service – Mental Health March 2015 Vol 22 No.1 ISSN 1323–1251 The Non -BZD hypnotics such as zolpidem and Introduction zopiclone (Z-drugs) are more selective for the alpha-1 subclass which seems to drive sleepiness but not anti-anxiety. Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are one of the most commonly prescribed medications for the treatment Table 1: BZDs and relative half-lives9,10 of insomnia and anxiety. 1 They are also frequently used to treat psychiatric emergencies, epilepsy, severe muscle spasm, acute alcohol withdrawal, Drug name Half -life (hours) anaesthesia and intensive care. Short -acting Triazolam 2 However, the use of BZDs is often controversial as Alprazolam 6-12 they are widely acknowledged to be addictive and Oxazepam 4-15 withdrawal symptoms can occur after 4-6 weeks of Temazepam 8-22 continuous use. This had led to the recommendation Medium -acting that they should not be used as hypnotics or Bromazepam 10 -20 anxiolytics for longer than 4 weeks. 2 In older age, Lorazepam 10 -20 BZDs also have serious adverse effects, including increased risk of falls, road traffic accidents and Long -acting 3,4 Clobazam 12 -60 cognitive impairment. Clonazepam 18 -50 More recently the risks of long term BZD use have Diazepam 20 -100 received greater focus with new evidence Flunitrazepam 18 -26 demonstrating a link between BZD use and the Nitrazepam 15 -38 5 development of Alzheimer’s disease and also 6 increased risk of mortality. Benzodiazepine use in Psychiatry Given the wide spread usage of these medications and the associated risk, this bulletin reviews BZDs Sleep disorders with particular emphasis upon adverse effects, dependence and abuse potential. -

About Your Medication CLOBAZAM

About your medication CLOBAZAM (Frisium® 10mg) Other brands may be available WHAT IS CLOBAZAM? Clobazam is from a group of medications known as benzodiazepines. It is only available on a doctor’s prescription. WHAT IS IT FOR? It can be used for treatment of anxiety (short term only), sleep disturbances associated with anxiety and control of seizures (fits) in patients with epilepsy. It works by acting on an imbalance of chemicals in the brain. HOW TO TAKE THIS MEDICINE It is important that this medication is taken only as directed and not given to other people. Treatment should be reviewed regularly by your doctor Tablets may be crushed for swallowing and can be given with food or on an empty stomach. This medication should be taken at the same time each day for best effects. WHAT TO DO IF A DOSE IS MISSED If you miss a dose of the medication it can be taken as soon as you remember. Do not take the missed dose if it is close to the next one, just take the next dose as normal. Do not double up on any doses. STORING THE MEDICINE It is important to keep clobazam locked away out of the reach of children. Do not keep the tablets in the bathroom, near the kitchen sink or in other damp, warm places because this may make them less effective. Store in a cool, dry place, away from heat and direct sunlight. USE OF OTHER MEDICINES Care must be taken when using clobazam with some other medications. Check with your doctor or pharmacist before giving any other prescription medicine, or medicine purchased without a prescription from a pharmacy, supermarket, or health food shop. -

List of Formulary Drug Removals

July 2021 Formulary Drug Removals Below is a list of medicines by drug class that have been removed from your plan’s formulary. If you continue using one of the drugs listed below and identified as a Formulary Drug Removal, you may be required to pay the full cost. If you are currently using one of the formulary drug removals, ask your doctor to choose one of the generic or brand formulary options listed below. Category Formulary Drug Formulary Options Drug Class Removals Acromegaly SANDOSTATIN LAR SOMATULINE DEPOT SIGNIFOR LAR SOMAVERT Allergies dexchlorpheniramine levocetirizine Antihistamines Diphen Elixir RyClora CARBINOXAMINE TABLET 6 MG Allergies BECONASE AQ flunisolide spray, fluticasone spray, mometasone spray, DYMISTA Nasal Steroids / Combinations OMNARIS QNASL ZETONNA Anticonvulsants topiramate ext-rel capsule carbamazepine, carbamazepine ext-rel, clobazam, divalproex sodium, (generics for QUDEXY XR only) divalproex sodium ext-rel, gabapentin, lamotrigine, lamotrigine ext-rel, levetiracetam, levetiracetam ext-rel, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, phenytoin sodium extended, primidone, rufinamide, tiagabine, topiramate, valproic acid, zonisamide, FYCOMPA, OXTELLAR XR, TROKENDI XR, VIMPAT, XCOPRI BANZEL SUSPENSION clobazam, lamotrigine, rufinamide, topiramate, TROKENDI XR ONFI SABRIL vigabatrin ZONEGRAN carbamazepine, carbamazepine ext-rel, divalproex sodium, divalproex sodium ext-rel, gabapentin, lamotrigine, lamotrigine ext-rel, levetiracetam, levetiracetam ext-rel, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, phenytoin sodium