Lower Karnali Watershed Profile: Status, Challenges and Opportunities for Improved Water Resource Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001

P|D|LL|S G8 G10 Code Under Name Girls Boys Total Girls Boys Total 010290001 Maiwakhola Gaunpalika Patidanda Ma Vi 15 22 37 25 17 42 010360002 Meringden Gaunpalika Singha Devi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 8 2 10 0 0 0 010370001 Mikwakhola Gaunpalika Sanwa Ma V 27 26 53 50 19 69 010160009 Phaktanglung Rural Municipality Saraswati Chyaribook Ma V 28 10 38 33 22 55 010060001 Phungling Nagarpalika Siddhakali Ma V 11 14 25 23 8 31 010320004 Phungling Nagarpalika Bhanu Jana Ma V 88 77 165 120 130 250 010320012 Phungling Nagarpalika Birendra Ma V 19 18 37 18 30 48 010020003 Sidingba Gaunpalika Angepa Adharbhut Vidyalaya 5 6 11 0 0 0 030410009 Deumai Nagarpalika Janta Adharbhut Vidyalaya 19 13 32 0 0 0 030100003 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Janaki Ma V 13 5 18 23 9 32 030230002 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Singhadevi Adharbhut Vidyalaya 7 7 14 0 0 0 030230004 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Jalpa Ma V 17 25 42 25 23 48 030330008 Phakphokthum Gaunpalika Khambang Ma V 5 4 9 1 2 3 030030001 Ilam Municipality Amar Secondary School 26 14 40 62 48 110 030030005 Ilam Municipality Barbote Basic School 9 9 18 0 0 0 030030011 Ilam Municipality Shree Saptamai Gurukul Sanskrit Vidyashram Secondary School 0 17 17 1 12 13 030130001 Ilam Municipality Purna Smarak Secondary School 16 15 31 22 20 42 030150001 Ilam Municipality Adarsha Secondary School 50 60 110 57 41 98 030460003 Ilam Municipality Bal Kanya Ma V 30 20 50 23 17 40 030460006 Ilam Municipality Maheshwor Adharbhut Vidyalaya 12 15 27 0 0 0 030070014 Mai Nagarpalika Kankai Ma V 50 44 94 99 67 166 030190004 Maijogmai Gaunpalika -

Website Disclosure Subsidy.Xlsx

Subsidy Loan Details as on Ashad End 2078 S.N Branch Name Province District Address Ward No 1 Butwal SHIVA RADIO & SPARE PARTS Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-06,RUPANDEHI,TRAFFIC CHOWK 6 2 Sandhikharkaka MATA SUPADEURALI MOBILE Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-06,RUPANDEHI 06 3 Butwal N G SQUARE Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-11,KALIKANAGAR 11 4 Butwal ANIL KHANAL Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-5,MANIGARAM 5 5 Butwal HIMALAYAN KRISHI T.P.UDH.PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-05,RUPANDEHI,MANIGRAM 5 6 Butwal HIMALAYAN KRISHI T.P.UDH.PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-05,RUPANDEHI,MANIGRAM 5 7 Butwal HIMALAYAN KRISHI T.P.UDH.PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi TILOTTAMA-05,RUPANDEHI,MANIGRAM 5 8 Butwal HARDIK POULTRY FARM Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHA BHUMI-02,KAPILBASTU 2 9 Butwal HARDIK POULTRY FARM Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHA BHUMI-02,KAPILBASTU 2 10 Butwal HARDIK POULTRY FARM Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHA BHUMI-02,KAPILBASTU 2 11 Butwal RAMNAGAR AGRO FARM PVT.LTD Lumbini Nawalparasi SARAWAL-02, NAWALPARASI 2 12 Butwal RAMNAGAR AGRO FARM PVT.LTD Lumbini Nawalparasi SARAWAL-02, NAWALPARASI 2 13 Butwal BUDDHA BHUMI MACHHA PALAN Lumbini Kapilbastu BUDDHI-06,KAPILVASTU 06 14 Butwal TANDAN POULTRY BREEDING FRM PVT.LTD Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-11,RUPANDEHI,KALIKANAGAR 11 15 Butwal COFFEE ROAST HOUSE Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-09,RUPANDEHI 09 16 Butwal NUTRA AGRO INDUSTRY Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL 13 BELBAS, POUDEL PATH 13 17 Butwal SHUVA SAMBRIDDHI UNIT.AG.F PVT.LTD. Lumbini Rupandehi SAINAMAINA-1, KASHIPUR,RUPANDEHI 1 18 Butwal SHUVA SAMBRIDDHI UNIT.AG.F PVT.LTD. Lumbini Rupandehi SAINAMAINA-1, KASHIPUR,RUPANDEHI 1 19 Butwal SANGAM HATCHERY & BREEDING FARM Lumbini Rupandehi BUTWAL-09, RUPANDEHI 9 20 Butwal SHREE LAXMI KRISHI TATHA PASUPANCHH Lumbini Palpa TANSEN-14,ARGALI 14 21 Butwal R.C.S. -

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal Volumes: Volume I : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 1 Volume II : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 2 Volume III : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 3 Volume IV : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 4 Volume V : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 5 Volume VI : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 6 Volume VII : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 7 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Forest Research and Survey Kathmandu July 2017 © Department of Forest Research and Survey, 2017 Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part should mention the title and credit DFRS. Citation: DFRS, 2017. Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal. Department of Forest Research and Survey (DFRS). Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared by: Coordinator : Dr. Deepak Kumar Kharal, DG, DFRS Member : Dr. Prem Poudel, Under-secretary, DSCWM Member : Rabindra Maharjan, Under-secretary, DoF Member : Shiva Khanal, Under-secretary, DFRS Member : Raj Kumar Rimal, AFO, DoF Member Secretary : Amul Kumar Acharya, ARO, DFRS Published by: Department of Forest Research and Survey P. O. Box 3339, Babarmahal Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4233510 Fax: 977-1-4220159 Email: [email protected] Web: www.dfrs.gov.np Cover map: Front cover: Map of Forest Cover of Nepal FOREWORD Forest of Nepal has been a long standing key natural resource supporting nation's economy in many ways. Forests resources have significant contribution to ecosystem balance and livelihood of large portion of population in Nepal. Sustainable management of forest resources is essential to support overall development goals. -

The Kamaiya System of Bonded Labour in Nepal

Nepal Case Study on Bonded Labour Final1 1 THE KAMAIYA SYSTEM OF BONDED LABOUR IN NEPAL INTRODUCTION The origin of the kamaiya system of bonded labour can be traced back to a kind of forced labour system that existed during the rule of the Lichhabi dynasty between 100 and 880 AD (Karki 2001:65). The system was re-enforced later during the reign of King Jayasthiti Malla of Kathmandu (1380–1395 AD), the person who legitimated the caste system in Nepali society (BLLF 1989:17; Bista 1991:38-39), when labourers used to be forcibly engaged in work relating to trade with Tibet and other neighbouring countries. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Gorkhali and Rana rulers introduced and institutionalised new forms of forced labour systems such as Jhara,1 Hulak2, Beth3 and Begar4 (Regmi, 1972 reprint 1999:102, cited in Karki, 2001). The later two forms, which centred on agricultural works, soon evolved into such labour relationships where the workers became tied to the landlords being mortgaged in the same manner as land and other property. These workers overtimes became permanently bonded to the masters. The kamaiya system was first noticed by anthropologists in the 1960s (Robertson and Mishra, 1997), but it came to wider public attention only after the change of polity in 1990 due in major part to the work of a few non-government organisations. The 1990s can be credited as the decade of the freedom movement of kamaiyas. Full-scale involvement of NGOs, national as well as local, with some level of support by some political parties, in launching education classes for kamaiyas and organising them into their groups culminated in a kind of national movement in 2000. -

1.2 District Profile Kailali English Final 23 March

"Environmnet-friendly Development, Maximum Use of Resources and Good Governance Overall Economic, Social and Human Development; Kailali's Pridefulness" Periodic District Development Plan (Fiscal Year 2072/073 − 2076/077) First Part DISTRICT PROFILE (Translated Version) District Development Committee Kailali March 2015 Document : Periodic District Development Plan of Kailali (F/Y 2072/73 - 2076/77) Technical Assistance : USAID/ Sajhedari Bikaas Consultant : Support for Development Initiatives Consultancy Pvt. Ltd. (SDIC), Kathmandu Phone: 01-4421159, Email : [email protected] , Web: www.sdicnepal.org Date March, 2015 Periodic District Development Plan (F/Y 2072/073 - 2076/77) Part One: District Profile Abbreviation Acronyms Full Form FY Fiscal year IFO Area Forest Office SHP Sub Health Post S.L.C. School Leaving Certificate APCCS Agriculture Production Collection Centres | CBS Central Bureau of Statistics VDC Village Development Committee SCIO Small Cottage Industry Office DADO District Agriculture Development Office DVO District Veterinary Office DSDC District Sports Development Committee DM Dhangadhi Municipality PSO Primary Health Post Mun Municipality FCHV Female Community Health Volunteer M Meter MM Milimeter MT Metric Ton TM Tikapur Municipality C Centigrade Rs Rupee H Hectare HPO Health Post HCT HIV/AIDS counselling and Testing i Periodic District Development Plan (F/Y 2072/073 - 2076/77) Part One: District Profile Table of Contents Abbreviation .................................................................................................................................... -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Diagnostic of Selected Sectors in Nepal

GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GENDER EQUALITY AND SOCIAL INCLUSION DIAGNOSTIC OF SELECTED SECTORS IN NEPAL OCTOBER 2020 ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2020 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 8632 4444; Fax +63 2 8636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2020. ISBN 978-92-9262-424-8 (print); 978-92-9262-425-5 (electronic); 978-92-9262-426-2 (ebook) Publication Stock No. TCS200291-2 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22617/TCS200291-2 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. -

Table of Province 05, Preliminary Results, Nepal Economic Census

Number of Number of Persons Engaged District and Local Unit establishments Total Male Female Rukum East District 1,020 2,753 1,516 1,237 50101PUTHA UTTANGANGA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 276 825 501 324 50102SISNE RURAL MUNICIPALITY 464 1,164 620 544 50103BHOOME RURAL MUNICIPALITY 280 764 395 369 Rolpa District 5,096 15,651 8,518 7,133 50201SUNCHHAHARI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 302 2,231 1,522 709 50202THAWANG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 244 760 362 398 50203PARIWARTAN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 457 980 451 529 50204SUKIDAHA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 408 408 128 280 50205MADI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 407 881 398 483 50206TRIBENI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 372 1,186 511 675 50207ROLPA MUNICIPALITY 1,160 3,441 1,763 1,678 50208RUNTIGADHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 560 3,254 2,268 986 50209SUBARNABATI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 882 1,882 845 1,037 50210LUNGRI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 304 628 270 358 Pyuthan District 5,632 22,336 12,168 10,168 50301GAUMUKHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 431 1,716 890 826 50302NAUBAHINI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 621 1,940 1,059 881 50303JHIMARUK RURAL MUNICIPALITY 568 2,424 1,270 1,154 50304PYUTHAN MUNICIPALITY 1,254 4,734 2,634 2,100 50305SWORGADWARI MUNICIPALITY 818 2,674 1,546 1,128 50306MANDAVI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 427 1,538 873 665 50307MALLARANI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 449 2,213 1,166 1,047 50308AAIRAWATI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 553 3,477 1,812 1,665 50309SARUMARANI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 511 1,620 918 702 Gulmi District 9,547 36,173 17,826 18,347 50401KALI GANDAKI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 540 1,133 653 480 50402SATYAWOTI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 689 2,406 1,127 1,279 50403CHANDRAKOT RURAL MUNICIPALITY 756 3,556 1,408 2,148 -

Annex 1 : - Srms Print Run Quantity and Detail Specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts)

Annex 1 : - SRMs print run quantity and detail specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts) Number Number Number Titles Titles Titles Total numbers Cover Inner for for for of print of print of print # of SN Book Title of Print run Book Size Inner Paper Print Print grade grade grade run for run for run for Inner Pg (G1, G2 , G3) (Color) (Color) 1 2 3 G1 G2 G3 1 अनारकल�को अꅍतरकथा x - - 15,775 15,775 24 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 2 अनौठो फल x x - 16,000 15,775 31,775 28 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 3 अमु쥍य उपहार x - - 15,775 15,775 40 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 4 अत� र बु饍�ध x - 16,000 - 16,000 36 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 5 अ쥍छ�को औषधी x - - 15,775 15,775 36 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 6 असी �दनमा �व�व भ्रमण x - - 15,775 15,775 32 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 7 आउ गन� १ २ ३ x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 8 आज मैले के के जान� x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 9 आ굍नो घर राम्रो घर x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 10 आमा खुसी हुनुभयो x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 11 उप配यका x - - 15,775 15,775 20 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4X4 12 ऋतु गीत x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 13 क का �क क� x 16,000 - - 16,000 16 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 14 क दे�ख � स륍म x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 15 कता�तर छौ ? x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 -

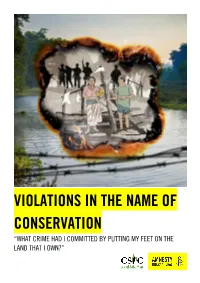

Violations in the Name of Conservation “What Crime Had I Committed by Putting My Feet on the Land That I Own?”

VIOLATIONS IN THE NAME OF CONSERVATION “WHAT CRIME HAD I COMMITTED BY PUTTING MY FEET ON THE LAND THAT I OWN?” Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. © Amnesty International 2021 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Illustration by Colin Foo (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Photo: Chitwan National Park, Nepal. © Jacek Kadaj via Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2021 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 31/4536/2021 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1.1 PROTECTING ANIMALS, EVICTING PEOPLE 5 1.2 ANCESTRAL HOMELANDS HAVE BECOME NATIONAL PARKS 6 1.3 HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY THE NEPAL ARMY 6 1.4 EVICTION IS NOT THE ANSWER 6 1.5 CONSULTATIVE, DURABLE SOLUTIONS ARE A MUST 7 1.6 LIMITED POLITICAL WILL 8 2. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

Groundwater Research in NEPAL for Tiger Conservation

GROUNDWATER RESEARCH IN NEPAL FOR TIGER CONSERVATION A reconnaissance study to groundwater dynamics in an alluvial mega-fan in Bardiya National Park (Terai), focusing on the interaction between groundwater and the Karnali river. Author: Hanne. Berghuis. MSc. Thesis. Program: Earth, Surface and Water at Utrecht University. 1st Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Jasper Griffioen. 2nd Supervisor: Dr. Derek Karssenberg. Date: 28-06-2019. Student No.: 6190987. Contact: [email protected]. Photo credits: Esther Leystra (2019). Nepal: Bardiya National Park. Acknowledgement I’d like to thank my supervisor Jasper Griffioen for the opportunity to hydrologically explore Bardiya. His enthusiasm for the project was inspiring and his close involvement was very motivating. My friend Ewa van Kooten introduced me to this project. Together we travelled to Nepal for three months. Thanks to her I enjoyed every single day of our time in Bardiya. She often came up with new ideas for field measurements, creative ways to fabricate field equipment or interpretations for unexpected observations. I am grateful for the Himalayan Tiger Foundation (HTF), who took the initial initiative for hydrological research in Bardiya. I very much appreciate their efforts for the conservation of the wild tiger. During the meetings in the Netherlands and around the campfire in Bardiya with the members and co of HTF, I have learned and laughed a lot. Moreover, I like to thank them for getting us in touch with the National Trust for Nature Conservation (NTNC). The staff of NTNC heartily welcomed us in Bardiya and at their office. They made us feel like a part of the NTNC-family by letting us join their festivals, dinners and campfires.