Scoreboard, Baby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

Coach Mike Holmgren January 12, 2007 (On the Status of the Team…) “I

Coach Mike Holmgren January 12, 2007 (On the status of the team…) “I think we are as prepared as we could be. We have some things we are going to do in Chicago tomorrow, but the physical part of the practice is over. I think the attitude is good, we’re prepared to play a really fine football team, we know that, but we will give it a go, we’re ready.” (On the status of Darrell Jackson and DJ Hackett…) “Those will be Sunday decisions. They did not practice as you know, and they are going to have to show me on Sunday that they can do something. But I am hopeful that I will have one or maybe both of them on Sunday.” (On how this team is different than the one that played the Bears earlier in the season…) “Well, some guys are going to be playing that didn’t play that first game. Some guys are going to be playing at different positions. From a practical standpoint, that is real. I think in the playoffs, when you are thinking about the finality of playoff football, I think probably both teams in their minds, may be a little different than a regular season game, but I am glad we have a couple guys that can play that didn’t play in the first game.” (On how the special teams practice went this week…) “I think it went fine. That is a situation where we, I referenced it earlier in the week, where you are having to sign guys to come in and play, and you are having to move guys up because of different situations, we’ve lost a couple key guys on special teams, but we’re counting on the new guys to come in, fill in and do their jobs. -

Parking Problems Persist

1 ACCENT FOOTBALL INSIDE • Residential • The Hurricane previews the NEWS: The UC bowling alley is being replaced by College roommates at upcoming game between the the career placement UM can be a blessing Hurricanes and 19th-ranked center and convenience Washington Huskies in this special store. Page 2 > ... or a curse. l_>t__M_U_____ ~'*' __i________*. _*______! section. OPINION: Top 10 reasons why Clinton's crime bill Page 8 Hurricane Magazine won't work. Page 4 GW)e Jffltamt ©urrtcane VOLUME 72. NUMBER 7 CORAL GABLES. FLA. SEPTEMBER 23. 1994 Parking problems persist PONCE REPAVED Garage opening FOR SUMMIT Students approaching or leaving in two months campus via Ponce De Leon Boule vard may have found a torn up road and slow traffic. The road, which runs along the By SARA FREDERICK "I think people are a Little lazy west edge of the campus, is cur Hurricane Staff Writer and don't want to walk," Cochez rently being resurfaced. Getting to class on time each day said. "People have a preconceived Carlos Catter, equipment man has become a major concern for notion of how far they should have ager of Pan-American Construc students who commute to the Uni to walk. Even if you park in the tion, said the construction would be versity. Part of the problem is back of the lot, it's not that far." finished relatively soon. because the newly constructed "It will probably be two weeks," parking garage is still not com Some UM employees have also Catter said. "Right now I have got pleted. encountered problems with stu about 10 guys working. -

Denver Broncos Vs Seattle Seahawks Sunday, November 17, 2002

Denver Broncos vs Seattle Seahawks Sunday, November 17, 2002 at Seahawks Stadium SEAHAWKS SEAHAWKS OFFENSE SEAHAWKS DEFENSE BRONCOS No Name Pos WR 81 K.Robinson 88 J.Williams 85 A.Bannister LDE 92 L.King 91 A.Palepoi No Name Pos 10 Feagles,Jeff P LT 71 W.Jones 68 D.Norman LDT 90 C.Eaton 98 C.Woodard 1 Elam,Jason K 17 Kelly,Jeff QB 11 Beuerlein,Steve QB 20 Morris,Maurice RB LG 62 C.Gray RDT 93 J.Randle 99 R.Bernard 14 Griese,Brian QB 21 Lucas,Ken CB C 61 R.Tobeck 68 D.Norman RDE 78 A.Cochran 95 J.Hilliard 17 Jackson,Jarious QB 24 Springs,Shawn CB 21 Coleman,KaRon RB 25 Tongue,Reggie S RG 69 F.Wedderburn OLB 55 M.Bell 54 D.Lewis 51 A.Simmons 22 Gary,Olandis RB 27 Williams,Willie CB RT 77 F.Womack 70 J.Wunsch 74 M.Hill MLB 57 O.Huff 53 K.Miller 58 I.Kacyvenski 23 Middlebrooks,Willie S 28 Blackmon,Harold S 24 O'Neal,Deltha CB 29 Fuller,Curtis S TE 89 I.Mili 86 J.Stevens 83 R.Hannam OLB 59 T.Terry 56 T.Killens 25 Walker,Denard CB 3 George,Jeff QB WR 88 J.Williams 84 B.Engram 87 K.Kasper LCB 24 S.Springs 27 W.Williams 42 K.Richard 26 Portis,Clinton RB 31 Robertson,Marcus S 28 Kennedy,Kenoy S 33 Evans,Doug CB 82 D.Jackson RCB 21 K.Lucas 33 D.Evans 31 Herndon,Kelly CB 34 Bierria,Terreal S QB 8 M.Hasselbeck 3 J.George 17 J.Kelly SS 25 R.Tongue 28 H.Blackmon 33 Spencer,Jimmy CB 37 Alexander,Shaun RB 34 Droughns,Reuben RB 38 Strong,Mack FB FB 38 M.Strong 44 H.Evans FS 31 M.Robertson 29 C.Fuller 34 T.Bierria 35 Walls,Lenny CB 42 Richard,Kris CB RB 37 S.Alexander 20 M.Morris 37 Poole,Tyrone CB 44 Evans,Heath FB 38 Anderson,Mike RB 51 Simmons,Anthony LB 4 Knorr,Micah P/K 52 Darche,J.P. -

19 12 History I (3).Indd

2016 UCLA FOOTBALL 1919: FRED W. COZENS 1927: WILLIAM H. SPAULDING 1934: WILLIAM H. SPAULDING 1940: EDWIN C. HORRELL 10/3 L 0 at Manual Arts HS 74 9/24 W 33 Santa Barbara St. 0 9/22 W 14 Pomona 0 9/27 L 6 SMU 9 10/10 L 6 at Hollywood HS 19 10/1 W 7 Fresno State 0 9/22 W 20 San Diego State 0 10/4 L 6 Santa Clara 9 10/17 L 12 at Bakersfi eld HS 27 10/8 W 25 Whittier 6 9/29 L 3 at Oregon 26 10/12 L 0 Texas A&M 7 10/24 W 7 Occidental Frosh 2 10/15 W 8 Occidental 0 10/13 W 16 Montana 0 10/19 L 7 at California 9 10/30 W 7 Los Angeles JC 0 10/28 W 32 Redlands 0 10/20 L 0 at California 3 10/26 L 0 Oregon State 7 11/7 L 0 USS Idaho 20 11/5 T 7 Pomona 7 10/27 W 49 California Aggies 0 11/2 L 14 Stanford (6) 20 11/14 L 7 Los Angeles JC 21 11/12 W 13 at Caltech 0 11/3 L 0 Stanford 27 11/9 L 0 at Oregon 18 11/21 L 13 at Occidental Frosh 30 11/19 L 13 at Arizona 16 11/12 W 6 St. Mary’s 0 11/16 W 34 Washington State 26 52 Season totals 193 11/26 L 6 Drake 25 11/24 W 25 Oregon State 7 11/23 L 0 Washington (13) 41 W—2, L—6, T—0 144 Season totals 54 11/29 W 13 Loyola 6 11/30 L 12 at USC 28 W—6, L—2, T—1 (Joined Pacifi c Coast Conf.) 146 Season totals 69 79 Season totals 174 1920: HARRY TROTTER W—7, L—3, T—0 (6th in PCC) W—1, L—9, T—0 (8th in PCC) 10/2 L 0 at Pomona 41 1928: WILLIAM H. -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

Rick Neuheisel

HEAD COACH RICK NEUHEISEL HEAD FOOTBALL COACH :: 4th SEASON :: UCLA '84 Rick Neuheisel, who quarterbacked UCLA to victory in the 1984 Rose Bowl Twice in the 2008 season, the Bruins rallied late in the fourth quarter for vic- is entering his fourth year as head coach at his alma mater and will lead tories, including a nationally televised Labor Day evening contest versus Ten- the Bruins into battle in the new Pac-12 Conference this fall. The energetic nessee. In addition, he laid a solid foundation to build upon and that February and personable Neuheisel returned to UCLA in December of 2007 and has signed a second straight Top 10 recruiting class. Neuheisel is "relentlessly brought energy to the program. positive" and sees great things for the future of Bruin football. Last season, UCLA scored a big win on the road at then #4-ranked Texas; In the Spring of 2009, he participated in the second annual Coaches Tour to posted three-straight 250-yard rushing games while upping its rushing aver- the Middle East, visiting U.S. troops at various bases. age by over 60 yards per game; had a quarterback break the school record “Rick is an outstanding coach and recruiter. He is outgoing and personable; for completions in a game; and had two players named to the AP All-America and can motivate our players, fans and supporters,” said athletic director team. The Bruins' win at Texas was the Longhorn’s first home loss since 2007. Dan Guerrero at the time of Neuheisel’s hiring. “We believe he is well- The three straight 250-yard rushing games marked the first time a UCLA equipped to lead the program and attain the success all Bruin fans wish to team had achieved that feat since the 1993 season. -

Football League of Kazakhstan. Draft Results 06-Feb-2007 12:49 PM Eastern

www.rtsports.com Football League of Kazakhstan. Draft Results 06-Feb-2007 12:49 PM Eastern Football League of Kazakhstan. Draft Fabulous! Conference Wed., Aug 23 2006 5:30:00 PM Rounds: 15 Time Limit: Unlimited Round 1 Round 6 #1 The Fighing Flyers - Shaun Alexander, RB, SEA #1 Cletic's Happy Leprachauns - Jason Witten, TE, DAL #2 Elviswasasammichfan - Larry Johnson, RB, KAN #2 Altamont Pedos - Michael Vick, QB, ATL #3 Who's your Papi? - LaDainian Tomlinson, RB, SDG #3 dvyyyyyy swallows - Plaxico Burress, WR, NYG #4 Crescent City Rangers - Tiki Barber, RB, NYG #4 Fat Guys Taint - Matt Hasselbeck, QB, SEA #5 Brown Balls - Edgerrin James, RB, ARI #5 Hellcat Poodles - Jake Plummer, QB, DEN #6 Hellcat Poodles - Peyton Manning, QB, IND #6 Brown Balls - Joe Jurevicius, WR, CLE #7 Fat Guys Taint - Clinton Portis, RB, WAS #7 Crescent City Rangers - Darrell Jackson, WR, SEA #8 dvyyyyyy swallows - Rudi Johnson, RB, CIN #8 Who's your Papi? - Donovan McNabb, QB, PHI #9 Altamont Pedos - LaMont Jordan, RB, OAK #9 Elviswasasammichfan - Marc Bulger, QB, STL #10 Cletic's Happy Leprachauns - Carnell Williams, RB, TAM #10 The Fighing Flyers - Isaac Bruce, WR, STL Round 2 Round 7 #1 Cletic's Happy Leprachauns - Willis McGahee, RB, BUF #1 The Fighing Flyers - Brian Griese, QB, CHI #2 Altamont Pedos - Ronnie Brown, RB, MIA #2 Elviswasasammichfan - Chris Cooley, TE, WAS #3 dvyyyyyy swallows - Warrick Dunn, RB, ATL #3 Who's your Papi? - DeShaun Foster, RB, CAR #4 Fat Guys Taint - Julius Jones, RB, DAL #4 Crescent City Rangers - Javon Walker, WR, DEN #5 Hellcat -

A GLAZE of GLORY the Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE

THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON ALUMNI MAGAZINE DEC 1 4 A GLAZE OF GLORY The Sweet Success of Top Pot Doughnuts JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // SUSTAINABLE TRANSPORTATION RUBY // RISK MANAGEMENT // BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE // INFORMATION SYSTEMS PROJECT MANAGEMENT // CONTENT STRATEGY // ORACLE DATABASE ADMIN LOCALIZATION // PARALEGAL // MACHINE LEARNING // SUPPLY CHAIN LOGISTICS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH // GERONTOLOGY // BIOTECHNOLOGY // CIVIL ENGINEERING DEVOPS // DATA SCIENCE // MECHANICAL ENGINEERING // HEALTH CARE // HTML CONTENT STRATEGY // EDUCATION // PROJECT MANAGEMENT // INFORMATICS STATISTICAL ANALYSIS // E-LEARNING // CLOUD DATA MANAGEMENT // EDITING C++ // INFRASTRUCTURE PLANNING // LEADERSHIP // BIOSCIENCE // LINGUISTICS INFORMATION SCIENCE // AERONAUTICS & ASTRONAUTICS // APPLIED MATHEMATICS CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING // GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS // PYTHON UW ONLINE 2 COLUMNS MAGAZINE ONLINE.UW.EDU JOIN US ANY TIME, EVERYWHERE 20 ADVANCED DEGREES + 50 CERTIFICATES + 100S OF COURSES AEROSPACE ENGINEERING // PUBLIC HEALTH // C# // APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT BIOSTATISTICS // COMPUTATIONAL FINANCE // MANAGEMENT // PROGRAMMING BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION // BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT // INFORMATION SECURITY ANALYTICS // GIS // DATA VISUALIZATION // -

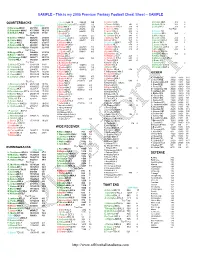

SAMPLE – This Is My 2005 Premium Fantasy Football Team Depth Chart – SAMPLE

SAMPLE - This is my 2005 Premium Fantasy Football Cheat Sheet – SAMPLE QUARTERBACKS T. Henry-TEN,10 326/45 0/0 K.Colbert-CAR, M.Pollard-DET, 309 6 D.Staley/W.Parker-PIT,4 830/55 1/0 A.Toomer-NYG,5 747 0 LJ.Smith-PHI,6 377 5 2004 Stats J.Bettis-PIT,4 941/46 13/0 J. McCareins-NYJ,8 770 4 D.Jolley-NYJ 313 2 P.Manning-IND,8 4577/38 49/0/10 D.Foster-CAR,7 255/76 2/0 P. Burress-NYG, 698 5 Tier Four D.Culpepper-MIN,5 4717/406 39/2/11 K.Barlow-SF,6 822/35 7/0 T. Glenn-DAL,9 400 2 B.Watson-NE D.McNabb-PHI,6 3875/220 31/3/8 F.Gore®-SF,6 M.Jenkins-ATL,8 119 0 D.Graham-NE,7 364 7 Tier Two L.Suggs-CLE,4 744/178 2/1 K. Johnson-DAL,9 981 6 B.Miller-HOU,3 K.Collins -OAK,5 3495/36 21/0/20 R.Droughns-CLE,4 1240/241 6/2 J.Galloway-TB,7 416 5 De.Clark-CHI,4 282 1 B. Favre-GB,6 4088/36 30/0/17 M.Turner-SD,10 392/17 3/0 B.Lloyd3-SF,6 565 6 J.Stevens-SEA,8 349 3 T. Green-KC,5 4591/85 27/0/17 R.Williams-MIA,4 M.Robinson-MIN,5 657 8 A.Becht-TB,7 100 1 C.Palmer-CIN,10 2897/47 18/1/18 E.Shelton®-CAR,7 D.Givens-NE,7 874 3 E.Conwell-NO,10 M.Hasselbeck-SEA,8 3382/90 22/1/15 M.Pittman-TB,7 926/391 7/3 R.Caldwell-SD,10 310 3 C.Anderson-OAK,5 128 1 Tier Three L.Johnson-KC,5 581/278 9/2 A.Bryant-CLE,4 812 4 A.Shea-CLE,4 252 4 G.Lewis®-PHI,6 E.Kinney-TEN,10 M.Bulger-STL,9 3964/89 21/3/14 T.J. -

2001 Husky Football

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON 2001 HUSKY FOOTBALL www.gohuskies.com Contacts: Jim Daves & Jeff Bechthold • (206) 543-2230 • Fax (206) 543-5000 2001 HUSKY SCHEDULE / RESULTS #15 WASHINGTON vs. ARIZONA Sept.8 MICHIGAN(ABC-TV) W,23-18 Huskies Return Home Looking to Rebound Sept.22 IDAHO W,53-3 THE GAME:TheWashingtonfootballteam(4-1overall,2-1inthePac-10)takesonunrankedArizona Sept.29 atCalifornia W,31-28 (3-3,0-3)inaPacific-10ConferencegamethisSaturday,Oct.20,atHuskyStadium.Gametimehasbeen Oct.6 USC(FoxSportsNet) W,27-24 re-scheduledfor3:30p.m.PDT.WashingtonisrankedNo.15inthelatestAssociatedPresspollandisthe Oct.13 atUCLA(ABC-TV) L,35-13 No.12teamintheESPN/USATodaycoaches’poll.TheHuskiesarelookingtoreboundfroma35-13loss Oct.20 ARIZONA(FoxSportsSyndicated) 3:30p.m. atUCLAlastweek,alossthatbroketheUW’s12-gamewinningstreak. Oct.27 atArizonaState 6:00p.m. Nov.3 STANFORD 12:30p.m. RESCHEDULING:Washington’sgameatMiami,originallyscheduledforSeptember15,waspost- Nov.10 atOregonState 1:00p.m. poneddueSept.11incidents.ThegamehasbeenrescheduledforNovember24,thoughnogametime Nov.17 WASHINGTONSTATE 12:30p.m. hasyetbeendetermined. Nov.24 atMiami,Fla. timeTBA alltimesarePacific THE SERIES:Washingtonholdsacommanding12-4-1edgeintheseriesagainstArizona,withthe Huskiestakingfiveofthelastsix.Overall,theHuskiesare26-12-1all-timeagainsttheArizonaschools 2001 PAC-10 STANDINGS (ArizonaandArizonaState),includinga14-5recordatHuskyStadium.Thelastthreegamesinthe Huskies’serieswithArizonahavebeendecidedbyatotalof14points,includingWashington’scome- Team Pac-10 Overall from-behind,35-32winlastyearinSeattle.TheHuskieshaveamasseda7-2recordatHuskyStadiumand -

Co-Defensive Coordinator Linebackers

Coaches WASHINGTON Coaches Head Coach Keith Gilbertson A well-respected coach in the Pacific Northwest for more than 20 years, when Washington won Keith Gilbertson was named the head football coach at Washington on July the national champion- 29. The Husky job is Gilbertson’s third stint as a head college coach. ship. The 1991 Washing- The 2003 season will be the ninth year of coaching at Washington for ton team led the Pac-10 Gilbertson. He is currently in his third term of service with the Husky in total offense, rushing program. He was a graduate assistant coach in 1975, an assistant coach offense and scoring of- from 1989-91 and again from 1999-2002. fense, relying on a bal- Gilbertson becomes the 24th coach in the program’s history. At age 55, anced attack he is the oldest individual to be named Washington’s head coach. Gilbertson In 2002, that offense replaces Rick Neuheisel, who was terminated by on June 12 after guiding was the most potent the Huskies to a 33-16 record over the past four seasons. passing attack ever seen Gilbertson’s previous head coaching experience includes stints at Idaho not only at Washington, (1986-88) and California (1992-95). He has a combined record of 48-35 at but in the Pac-10. Junior those two schools over seven seasons. quarterback Cody Pickett Gilbertson has been the Huskies’ offensive coordinator the last three smashed the Pac-10 seasons. He was also a graduate assistant coach at the UW in 1976, as record for single-season offensive line coach in 1998-90 and as the offensive coordinator in the passing yardage and national championship season of 1991.